Bullets zipped by him like a thunderstorm gone frenetic, whistling past his ears and slamming into the crumbling walls overhead. Minutes earlier the young Hispanic had bolted across the plaza to hole up in the tiny wood-and-adobe jacal—meager refuge from the coming hail of lead. Over the next 36 hours more than 4,000 rounds of ammunition would riddle the structure, tearing away parts of the house. Eight slugs were later pried from a broom handle.

Yet through it all the teen survived unscathed.

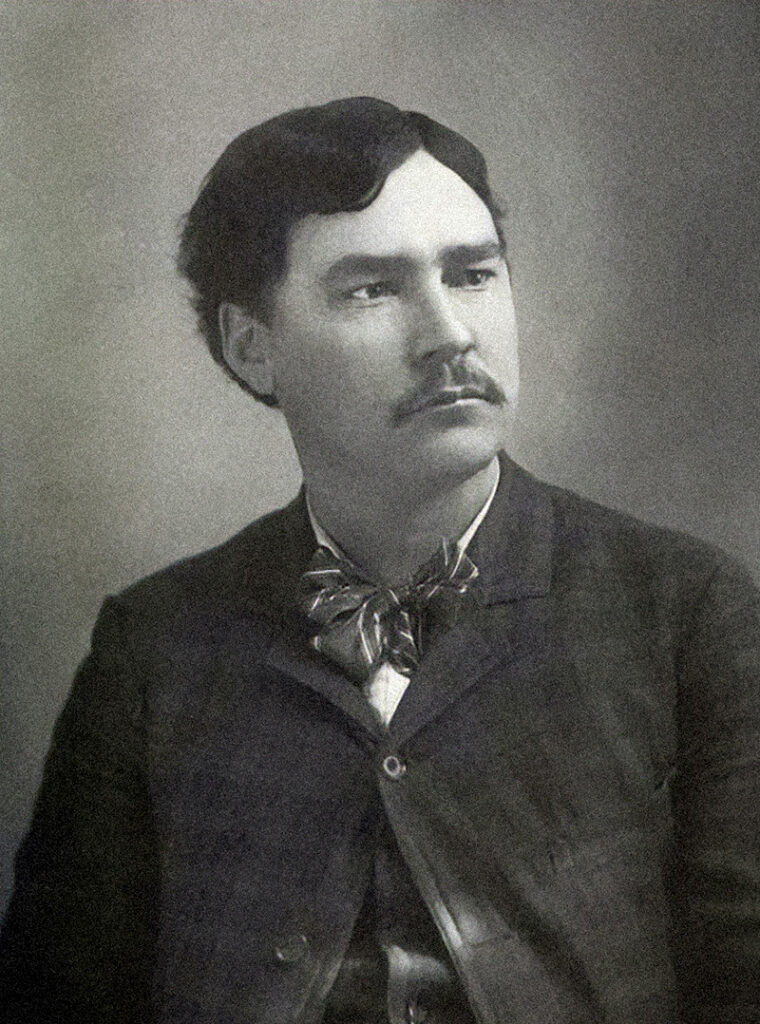

In late October 1884, in a dramatic display of skill, spunk and luck, unimposing 5-foot-7 19-year-old Elfego Baca instigated and prevailed in what was likely the most unequal civilian gunfight in the history of the American West. Certainly, it was the most unusual ever recorded.

Elfego’s Early Life

Many legends surround Elfego Baca, but a few facts are certain. On Feb. 27, 1865, he was born in Socorro, New Mexico Territory, to Francisco and Juana María Baca. The first legend has it his mother was playing las Iglesias, the Mexican version of softball, when her son emerged into the world right there on the field. Another legend claims Elfego was kidnapped in early childhood by Indians who immediately returned the toddler to his family after his screaming disturbed the serenity of the abductors’ camp.

A year after Baca’s birth his parents relocated the family to Topeka, Kan. There, surrounded by Anglos, Elfego grew up learning English and how to defend himself—using his wits before resorting to fists or gunplay, but never backing down.

Then, in early 1872 an unrecorded illness struck the family, claiming the lives of Baca’s mother, two sisters and a brother. Deciding to return to New Mexico Territory, Elfego’s father, Francisco, brought along eldest son Abdenago but left Elfego in the care of an orphanage. Settling in the small town of Belen, in Valencia County some 40 miles north of Socorro, the senior Baca was soon appointed marshal.

In 1880 15-year-old Elfego left the orphanage and made his way to Socorro, some 75 miles south of Albuquerque. There he reunited with brother Abdenago and other members of the Baca clan, later reconnecting with father Francisco. But it was to be a brief reunion for Elfego and his father. That December in the line of duty Marshal Baca shot into the midst of a drunken brawl in Belen, killing a man. Tried for murder the following spring, he was convicted of involuntary manslaughter. Francisco was being held in the Valencia County Jail, in Los Lunas, awaiting transfer to the Kansas State Penitentiary, in Lansing, when he and three other prisoners were “liberated” by Elfego and 15-year-old accomplice identified only as Chavez.

Newspapers reported details of the jailbreak, but only a few people knew of Elfego’s involvement. After escorting his father to El Paso, Texas, where Francisco could slip across the international border should need arise, Elfego returned to New Mexico Territory. Young Baca worked on his uncle’s isolated Socorro cattle ranch and then for a time in the Albuquerque area, where he transported meat by wagon to Santa Fe Railroad workers. But he always returned home to Socorro.

“Not Afraid”

From the 1880s into the ’90s Socorro was besieged by more than 3,000 miners without benefit of much law enforcement. Sheriffs were stretched thin, thus the town ran wide open 24 hours a day. One day in January 1883 liquored-up Texas cowboys staggered out of a Socorro saloon and rode through the Hispanic neighborhoods in a cloud of dust and bullets. County Sheriff Pete Simpson was in pursuit when he happened across Baca. Mounted and armed, Elfego, weeks shy of his 18th birthday, joined the chase at Simpson’s request. In an interview years later Baca claimed to have shot one of the fleeing horsemen from the saddle at better than 300 yards. Newspapers at the time reported that Simpson had made the shot, but Elfego remained cocky about the encounter. When asked if he knew the name of the dead cowboy, he replied flippantly, “He wasn’t able to tell me by the time I caught up with him.”

Though still wild and reckless in many respects, Elfego took a desk job at age 19 as a mercantile clerk for onetime Socorro judge and mayor Juan José Baca (not a relative), where the teen’s ability to speak both Spanish and English served him well. Though hardly as exciting as being a posse member, it beat being punching cows. Still, Elfego harbored ambitions of being a lawman.

In October 1884 Pedro Sarracino, a county sheriff and saloon owner from San Francisco Plaza, aka Frisco (present-day Reserve, N.M.), rode to Socorro to visit storeowner Baca, his brother-in-law. While there Sarracino mentioned to Elfego that several cattle ranches had sprung up in the Frisco area, and that their hands, mostly rowdy Texans, were running roughshod over local Hispanics. The chaos had recently come to a head when cowboys tortured and maimed a local man in Sarracino’s cantina. Outraged and full of teenage braggadocio, an outraged Elfego declared, “I will show the Texans there is at least one Mexican in the county who is not afraid of an American cowboy.” According to a 1924 autobiographical pamphlet, Baca volunteered on the spot to be Sarracino’s deputy. “I told him that if he would take me back to Frisco with him, that I would make myself a self-made deputy.” Elfego later claimed to have made his own badge. With that, the pair headed to Frisco, 110 miles west as the crow flies in far west-central New Mexico Territory.

The Legendary Fight

For two centuries before Anglo miners and trappers explored the region that today comprises western New Mexico and eastern Arizona the land supported several hundred Hispanic families. Farming, fishing and hunting kept the people well fed. Long before that, of course, the region had supported various sedentary Indian tribes.

In the 1880s cattlemen arrived from Texas and Oklahoma, daily swelling the population of sprawling San Francisco Plaza, a string of three settlements along the namesake river, which by 1884 had become a staging ground for cross-cultural sparring. Anglos sparred with Hispanics who sparred with Indians, and around it went. Adding fuel to the flames were heated arguments between the various cattle outfits—men who “rode for the brand” and took offense when someone from a competing ranch made an offhand comment. On the heels of the influx of rash young men more than a dozen saloons and bordellos sprang up in Middle and Lower Frisco. The valley was rife with tension.

Soon after Sarracino and young Baca arrived in town, Elfego stepped forward to make his first official arrest. On Oct. 29, 1884, inside the popular Milligan’s Whiskey Bar, drunken cowboy Charlie McCarty brandished his pistol at Hispanic patrons, ordering them to dance, then shot off Baca’s hat. Standing his ground, Baca flashed his badge at McCarty, who hailed from the John Bunyan Slaughter ranch, a notoriously rough Socorro County outfit. Somehow Elfego managed to take the man’s gun.

Cowboys gathered outside were unhappy to hear that this swaggering, self-deputized Hispanic hero had snagged their partner. Liquored up and ready to fight, the Slaughter cowboys leveled their Winchesters at the saloon, cocked at the ready. As angry shouts, curses and threats from the street resounded off the interior walls, Baca barricaded the saloon doors and windows.

The leader of the mob, Slaughter ranch foreman Young Parham, demanded McCarty’s release even while testing the doors and windows with his shoulders. Parham vowed he and his men would take their friend by force if necessary. Elfego hollered back from inside, threatening to shoot if the cowboys weren’t “out of there by the count of three.” The story goes that the ranch hands had begun to crack jokes about Elfego’s race being unable to count, when they heard him call out in a single quick breath, “One-two-three!” Baca and his “deputies”—friends who’d joined him inside—then fired several warning shots through the door.

In the resulting fusillade Parham had his horse shot out from under him, and as it collapsed, the horse crushed and killed him. Another cowboy caught a bullet through his knee. Out of ammunition and focused on caring for Parham, his horse and the wounded man, the ranch hands retreated, swearing vengeance against Baca and his deputies, who remained holed up at Milligan’s. Early the next morning Slaughter’s hands offered a compromise, vowing to leave be those inside the saloon if Baca would allow McCarty to be tried at a neighboring house. Elfego warily agreed and strolled next door with his ward.

At the speedy trial the justice of the peace fined the sobered-up McCarty $5 and ordered his release. By then, however, rumors had spread among the hands on surrounding ranches that Hispanics in Frisco had gone on a murderous rampage, killing and dismembering Anglo citizens. Seeking to mollify the gathering mob, the justice moved to detain Baca for questioning in Parham’s death.

Unwilling to be arrested, mobbed and undoubtedly lynched, Baca slipped out the “courtroom’s” side door and dashed across the plaza to a crude little jacal whose walls of mesquite sticks and dried mud would almost certainly not stop bullets. Evicting owner Geronimo Armijo and family, Elfego settled in for a siege. While much of the populace fled into the overlooking hills to watch the unfolding drama, some 80 vengeance-seeking ranch hands, using the adobe buttresses of a local church as cover, emptied their weapons into the jacal, reloaded and kept firing until its walls were full of holes.

Incredibly, none of the bullets struck Baca. All attempts to dislodge the teen were unsuccessful. He refused to come out. In frustration Burt Hearne, of the Spur outfit, rode up to the jacal, leapt from his horse and tried to force the door. Immediately, shots from inside struck Hearne in the stomach. He died within moments. The cowboy soon had company. In the long gunplay four of the vigilantes were killed, eight wounded. Late that evening someone lit a stick of dynamite and tossed it at the jacal. The resulting explosion collapsed the roof and one wall. To spectators and Baca’s attackers alike it seemed no one could have survived the blast. But none of the cowboys was willing to investigate in the darkness. They wisely decided to wait and sift the ruins soberly in the light of day.

As the morning sun peaked over the Mogollon Rim, the hands who’d spent the night sleeping on the cold ground around Baca’s hideout awoke to the aroma of steeping coffee and fresh tortillas—from inside the jacal. After a hearty breakfast the very much alive Baca resumed his watch. One hungry and enraged cowboy charged forward using a cast-iron shield pirated from a cookstove, only to flee and drop the armor after a slug creased his hairline.

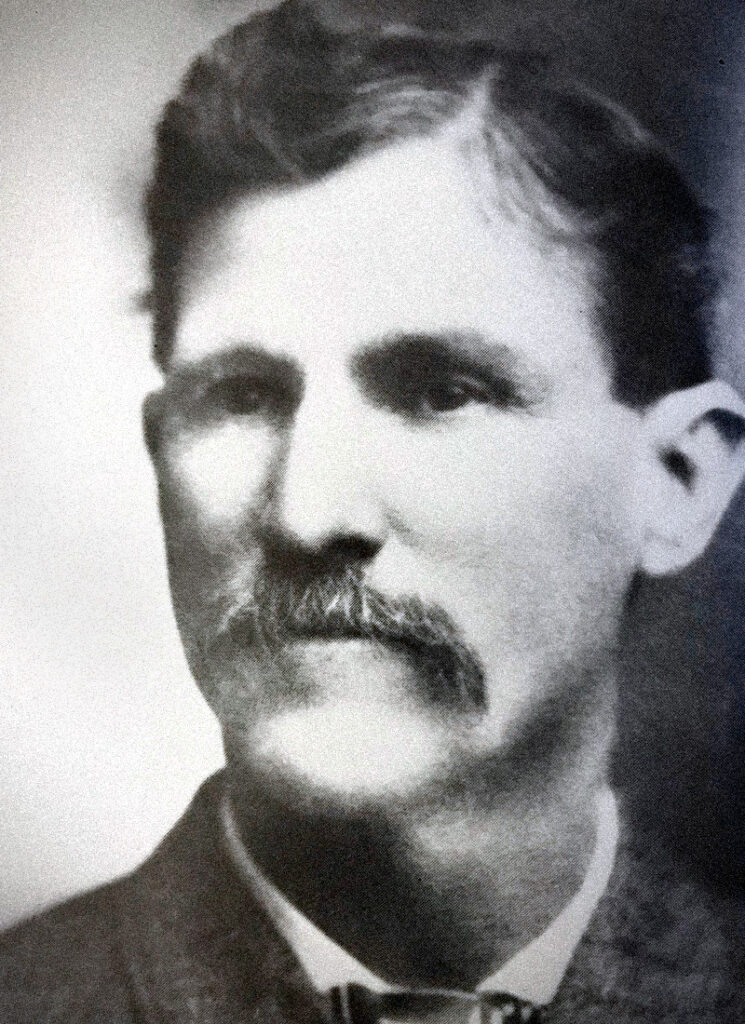

At 6 that evening, a day and a half after the first shots were fired, the battle ended when a bona fide Socorro County deputy sheriff, Frank Rose, persuaded Baca to surrender. Before doing so, Elfego insisted on two conditions: to stand trial in Socorro, and to retain his two pistols (one was McCarty’s). The next morning he rode in the back of a buckboard on the return trip to his hometown. Trailing cowboys were warned not to approach.

Back in Frisco curious onlookers pored over the jacal. Inside, they were astonished to find an intact plaster statue of Nuestra Señora Doña Ana. That Baca had survived was also considered a miracle—until his secret was revealed. The jacal’s floor was recessed 18 inches belowground, enough to have screened Elfego from the incoming barrage.

Yet Baca did seem to lead a charmed life, for an ambush planned for him on the road to Socorro also failed. Two separate groups of would-be assassins each mistakenly thought the other had carried out the attack. Meanwhile, the lawman arrived safely in custody in Socorro.

Charged with murder in the shooting of Hearne, Baca remained in jail until his trial in Albuquerque in May 1885. Among the items entered into evidence was the door of the jacal, bearing nearly 400 bullet holes. That and Sarracino’s testimony convinced the jury Elfego had indeed killed in self-defense. Subsequently tried and acquitted of murder in the death of Parham, Baca was immediately thrust into the status of folk hero to the local Hispanics.

A Colorful Career

Exploiting his notoriety from the Frisco shootout, Baca officially resumed his career as a deputy sheriff in Socorro. He was later elected county sheriff, with the power to secure indictments for the arrest of local lawbreakers. Instead of having his deputies risk life and limb in pursuit of the wanted men, he sent each of the accused a letter:

“I have a warrant here for your arrest. Please come in by [fill in date] and give yourself up. If you don’t, I’ll know you intend to resist arrest, and I will feel justified in shooting you on sight when I come after you.”

Most fugitives turned themselves in.

Shortly after his acquittal in 1885 Baca married 16-year-old Francisquita Pohmer. Despite alleged dalliances by Elfego, the couple remained together 60 years and raised two sons and four daughters.

In 1888 Baca was appointed a U.S. marshal and served two years. He then studied law and in 1894 was admitted to the bar. After working for respected jurist Alfred Alexander Freeman’s law firm in Socorro in 1895, Elfego operated his own practice on San Antonio Street in El Paso from 1902 to ’04.

Around 1910 he moved to Albuquerque, where he worked as both a lawyer and private detective. “Dressed in a flowing cape and trailed by a bodyguard, he stalked the downtown streets handing out business cards,” historian Marc Simmons writes. On the front of the card was printed Elfego Baca, Attorney-at-Law, Fees Moderate, on the reverse Private Detective, Divorce Investigations Our Specialty, Discreet Shadowing Done. As if being a private detective wasn’t exciting enough, Baca also worked a stint as a bouncer in a gambling house south of the border in Juárez, Chihuahua.

That period of his life spawned another legend. One day Baca received a telegram from a client in El Paso. “Need you at once,” it read. “Have just been charged with murder.” Attorney Baca supposedly responded with a tongue-in-cheek telegram reading, “Leaving at once with three eyewitnesses.”

When New Mexico achieved statehood in 1912, Baca ran for Congress as a Republican. Though unsuccessful, he remained a valued political figure for his ability to turn out the Hispanic vote. He held several other public offices in succession, including Socorro County clerk, Socorro County school superintendent, mayor of Socorro, and district attorney for Socorro and Sierra counties. “Most reports say he was the best peace officer Socorro ever had,” Leon Metz writes of Baca in his 1996 book The Shooters.

Still more adventures, with revolutionary overtones, awaited Elfego.

Another Escape

In February 1913, after a period of unremitting turmoil amid the Mexican Revolution, President Victoriano Huerta wrested control of the republic, though he continued to face challenges from guerrilla leaders in the northern provinces. Chief among them was Francisco “Pancho” Villa, who controlled much of the state of Chihuahua, bordering New Mexico.

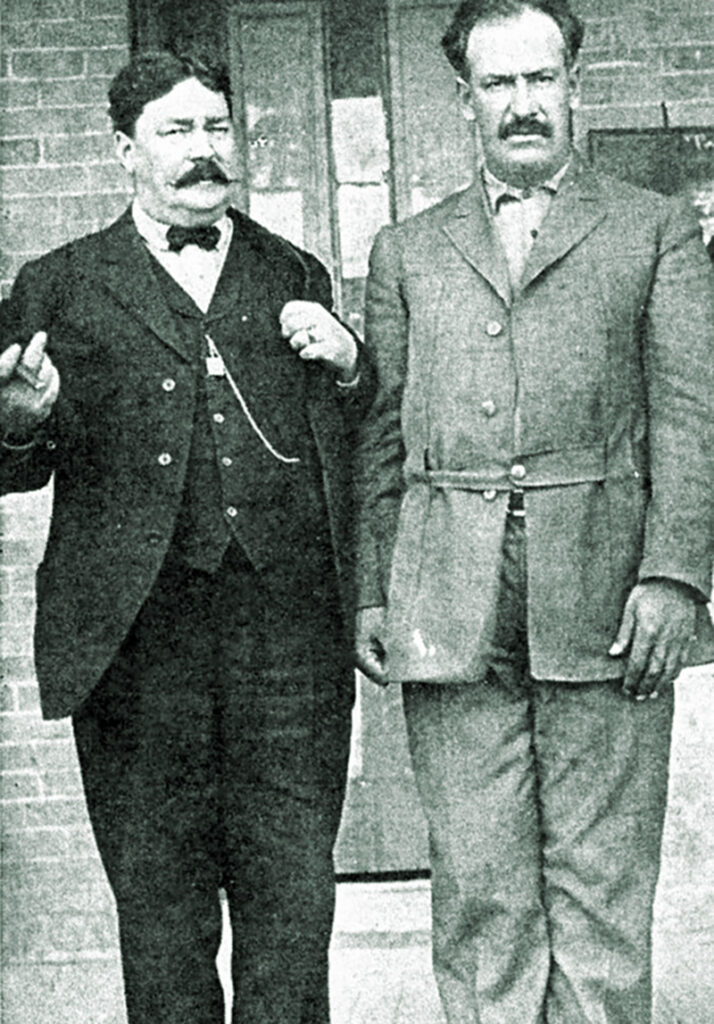

In early January 1914, hotly pursued by Villa’s army, Huerta-allied General José Inés Salazar crossed into Presidio, Texas. Almost at once he was arrested and charged with having violated American neutrality laws. Placed in military custody at Fort Bliss, outside El Paso, the general was later moved to Fort Wingate, near Gallup, New Mexico Territory.

President Huerta in particular wanted Salazar out of jail, and agents of the Mexican government sought the legal services of Baca, whose reputation had spread across the border. Baca traveled to Washington but failed to gain the general’s release. He then engaged in a series of legal shenanigans that garnered his client an additional perjury charge. On November 16 Salazar was transferred to the Bernalillo County Jail, in Baca’s hometown of Albuquerque, to face the charge. Four days later two masked men entered the jail, overpowered and bound the sheriff and sped off in a car with Salazar. He was last spotted in El Paso, headed south.

Word about town had it Huerta’s accomplices had arrived in Albuquerque beforehand and quietly contacted certain influential residents, providing them with substantial funds to arrange Salazar’s freedom. Some suspected Baca had been the ringleader. Yet Elfego had an ironclad alibi for his whereabouts on the night of the escape; he’d been drinking at the crowded Graham Bar in downtown Albuquerque and had even overtly asked a friend for the exact time so he could set his watch.

Regardless, in April 1915 a federal grand jury handed down indictments charging Baca and three other officials with conspiracy in Salazar’s escape. At their December trial all four were acquitted. Elfego’s reputation only soared among Hispanic admirers.

On Feb. 26, 1940, the day before Baca’s 75th birthday, he boasted to The Albuquerque Tribune that of the 30 people he had defended on charges of murder, only one was sent to the penitentiary. In later years Baca worked closely with longtime New Mexico Senator Bronson M. Cutting as a political investigator and wrote a weekly newspaper column in Spanish praising the senator’s work on behalf of local Hispanics. He even switched parties with Cutting in support of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1944, despite poor health, 79-year-old Baca considered running for governor, but that year he failed even to secure the Democratic Party’s nomination for district attorney.

“I Made ’em Believe it”

For more than six decades Baca remained a lively part of New Mexico’s cultural landscape, relating spirited memories of comely señoritas and political intrigues past. His miraculous deliverance from the 1884 Frisco shootout had earned this man of many facets a reputation as one tough hombre. That reputation followed him throughout his years as a lawman, criminal lawyer, district attorney, private detective, chief bouncer of a Prohibition gambling house and American agent for President Huerta.

On July 13, 1936, Janet Smith of the Federal Writers’ Project, part of the Roosevelt-era Works Progress Administration, conducted an interview with Baca, the notes from which are preserved in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. “I never wanted to kill anybody,” Baca told Smith, “but if a man had it in his mind to kill me, I made it my business to get him first.” Full of self-confidence throughout his life, Baca added, “In those days I was a self-made deputy. I had a badge I made for myself, and if they didn’t believe I was a deputy, they’d better believe it, because I made ’em believe it.”

As befitting a legend, New Mexico lawman Elfego Baca, who’d been born near the close of the Civil War in 1865, died at age 80 on Aug. 27, 1945, near the close of World War II. He is buried at Sunset Memorial Park in Albuquerque.

For further reading on this topic author Melody Groves recommends Memoirs: Episodes in New Mexico History, 1892–1969, by William A. Keleher; Incredible Elfego Baca: Good Man, Bad Man of the Old West, by Howard Bryan; and The Lost Frontier, by Rod Miller.