One of the most intriguing stories to emerge during World War II occurred just shy of a year after the Pearl Harbor attack and involved an American icon. The incident captured the attention of the free world and has been described as the first American epic of the war.

Captain Edward Vernon Rickenbacker had gained fame as a daring racecar driver before becoming the United States’ top-scoring fighter ace of World War I and a Medal of Honor recipient. After the war he delved first into the automobile industry and then wound his way back to aviation, eventually becoming president of Eastern Air Lines. Rickenbacker was a strong voice for aviation, on several occasions testifying before congressional committees about actions he felt would be detrimental to both military and civilian aviation.

In late 1942 Secretary of War Henry Stimson and Army Air Forces chief of staff General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold asked the 52-year-old airline executive to travel to the Pacific theater as a $1-a-day nonmilitary observer. His mission was to evaluate and report on the status of U.S. Army Air Forces combat units stationed there. His itinerary included visits to Australia, New Guinea and Guadalcanal.

Rickenbacker was accompanied on the mission by his aide, Colonel Hans Adamson. On October 20, 1942, they climbed aboard a well-worn Boeing B-17 in Hawaii that had been converted into a transport plane. The B-17 was crewed by Captain William Cherry Jr. of Abilene, Texas, pilot; Lieutenant James Whittaker of Burlingame, Calif., co-pilot; Lieutenant John De Angelis of Nesquehoning, Pa., navigator; Private John Bartek of Freehold, N.J., engineer; and Sergeant James Reynolds of Fort Jones, Calif., radio operator. Also along was Staff Sgt. Alexander Kaczmarczyk from Torrington, Conn., an enlisted airman who was returning to his outfit in Australia after recovering from a lengthy illness. The plane was also loaded with a large number of bags of high-priority mail and secret documents.

Thanks to a broken hydraulic line, the takeoff on the 20th had to be aborted. All onboard plus luggage, mail bags and navigation equipment were transferred to another B-17. They finally took off at 1:30 a.m. on October 21, bound for island ‘X’ (so designated for security reasons; actually Canton Island), about 1,800 miles to the southwest.

An hour before the estimated arrival time, Captain Cherry throttled back, slowly descended to about 1,000 feet and began looking for Canton Island. It never came into view. Thinking they had overshot their mark, Cherry and De Angelis made a 180-degree correction and began looking for their destination from the opposite direction. Again they saw nothing but ocean.

Reynolds kept in constant contact with personnel at Canton. He requested a bearing, but the island did not have the equipment to provide one. He next contacted another island, known as “Y,” for assistance and was told to circle at 5,000 feet for 30 minutes and to keep sending continuous radio signals. In the end, however, all Y could provide was a compass course reading, which was worthless since that did not tell the crew whether they were flying toward or away from their destination. Without a bearing the pilot did not know in which direction to fly.

There was no question about it now—they were lost. De Angelis offered one possible explanation: His octant had been aboard the plane during the aborted takeoff in Hawaii, and it might have been jarred enough to throw his observations off. Even a few degrees could have caused them to fly many miles to the right or left of their destination. The crew asked Canton to fire off anti-aircraft shells, set to explode above the clouds at 7,000 feet, and also to send out search planes in every direction. Nothing worked. Their only hope was to spot a ship, but that also proved fruitless.

At 1:30 p.m. the pilot told Rickenbacker they had only one hour of fuel remaining. Rickenbacker wrote out a note and gave it to the radio operator to send. It was the last message anyone received from the B-17. Reynolds continued sending out SOS signals while Cherry climbed to 5,000 feet for a better view and shut down two engines to conserve fuel. As the gas gauge neared zero, Cherry began preparing to ditch. Meanwhile, all hands were busy tossing out everything not considered essential to survival, including mail, a toolbox, cots, blankets and luggage, as well as Rickenbacker’s briefcase containing classified material. They filled thermos bottles with water, gathered emergency rations and other items and arranged them near the rear hatch to make it easier to get at them after ditching. Mattresses were propped against the bulkhead to cushion the men from the expected jolt, and everyone donned Mae West life jackets.

There were three self-inflating rubber rafts available, two with a listed capacity of five men that Bartek was set to expel by pulling cockpit levers, plus a two-man raft rolled up in the radio compartment. Cherry advised that, since the plane weighed 25 tons, they should not expect to have more than 30 to 60 seconds to exit the craft after splashdown. Rickenbacker stuffed a map, some official papers and his passport into his coat pockets. He also grabbed several handkerchiefs and a 60-foot line; both later proved to be godsends.

As Cherry started his long glide downward, the men braced themselves for the crash. Bartek was standing behind the pilot, holding onto the levers to release the two big rafts. Rickenbacker was strapped to his seat on the right-hand side, holding a pillow to protect his face. Adamson was sitting on the deck, bracing his back against a mattress. Reynolds remained at his radio, sending a constant series of SOS signals — hoping someone somewhere might establish a fix on them. About the time someone yelled ‘Only 50 feet left!’ one engine sputtered and died. Rickenbacker glanced out a window and could see that the ocean was rough, with high swells. In a moment the big plane did a soft but loud belly-flop in the middle of a trough and skipped another 50 feet before coming to a stop against the waning slope of a swell. As crash landings at sea go, this one was about as good as they got. Had Cherry misjudged the waves by only a few seconds, the plane and its passengers might have sunk immediately.

Green water immediately began gushing through smashed windows, making it impossible to salvage much of the survival equipment. Reynolds suffered from cuts on his hands and face, and his head had struck the radio panel, resulting in more bleeding. Adamson suffered a badly sprained back, but most of the injuries were manageable.

When the rafts were inflated and free, the pilots exited through the forward hatch and lent a hand to the passengers. Rickenbacker’s escape hatch was above a wing, so he helped the others climb out once he was outside the plane. The swells were well over six feet high, making the rafts extremely difficult to handle.

The 200-pound Adamson was helped into one of the big rafts to join Bartek, but when Rickenbacker squeezed his large frame into the same raft there was hardly room to move. It was like trying to shoehorn a size 10 foot into a size 9 brogan. Cherry, Whittaker and Reynolds crawled into the other big raft, but the small one was upside down, and Kaczmarczyk and De Angelis were having difficulty getting aboard. Meanwhile, Rickenbacker’s craft began floating aimlessly, and before he could free the raft’s two small oars it was tossed against the plane’s tail section and almost capsized.

The B-17 was still partially afloat, although by then it had begun settling deeper into the water. In all the confusion and yelling between the rafts, the men began looking for the water thermoses that had been so carefully stacked together prior to the crash. They were gone. They then discovered that the only food they had managed to salvage were four oranges Cherry had stuffed into his jacket pocket.

Rickenbacker’s 60 feet of line probably had more to do with their salvation than anything else. The crewmen tied the rafts 20 feet apart, which allowed them closer contact when problems arose, as well as the camaraderie so important in dire situations. Had the three rafts been allowed to float aimlessly around in the Pacific, it is doubtful that any of the men would have survived.

The men began to take stock of their clothing. Rickenbacker and Adamson were the only two fully dressed. Adamson had his cap and uniform, and Rickenbacker was in a business suit with shirt and tie and his felt hat. Most of the others had shed practically everything, including their shoes, expecting to have to swim after the crash. The pilots had held onto their leather jackets, but Bartek was wearing only a one-piece jumper.

A quick inventory of possessions showed they had a first-aid kit, a Very pistol with 18 flares, two hand pumps for bailing water and pumping air into the rafts, two sheath knives, a pair of pliers, a small compass, two collapsible bailing buckets, some patching gear for each raft, pencils and Rickenbacker’s map. Reynolds had grabbed two fishing lines, but there was no bait. The pilots had also kept their pistols.

The men were exhausted, and several were also violently seasick. Adamson’s back injury was very painful, while the others suffered from a variety of cuts and bruises. Sergeant Kaczmarczyk, who had been out of the hospital only a couple of weeks, was in serious trouble. He had swallowed a lot of seawater and needed more help than the others could provide. As the sun set, the temperature plunged. A three-quarter moon, although beautiful to look at, signaled the start of a long and lonely night. The men held an organizational meeting and set a series of two-hour watches, to keep alert for any serious problems and to be aware of any approaching ship or plane. It turned out there was little need for such sentinels — few if any of the men actually slept that night. Although the winds had subsided by midnight, waves continued to slosh icy-cold water into the boats, and the tired men spent most of the night bailing. Sharks followed the boats constantly.

On the second day, the men slowly recovered from the chill of night until midmorning, when the hot sun began its torture. The men decided to eat one of Cherry’s oranges. Voted the ‘orange custodian,’ Rickenbacker cut and doled them out. Each man’s eighth of an orange was the only food he would have for two days. Some ate peel and all, but Cherry and Rickenbacker saved their peels for fish bait.

The next six or seven days proved excruciating, as a glassy calm brought intolerable heat that blistered every inch of exposed flesh from the tops of their heads to the soles of their feet. Saltwater soaked into skin that cracked open and then dried, only to be soaked again. When the men developed runny sores on their mouths, they folded Rickenbacker’s handkerchiefs into triangles and placed them over nose and mouth “bandit fashion.”

During daytime, the men looked forward to the coolness of the nights, and at night they craved the heat of the days. Given a choice of the two, most preferred the days because they could see their companions and seagulls and watch the movement of waves. The nights were fearful, filled with frequent moans, cries and prayers.

Unable to stretch out at night, Rickenbacker later remarked that if he ever met the man who proclaimed those rafts held two and five men apiece he would demand that he prove his theory on a lengthy voyage under similar circumstances. In his five-man raft, Rickenbacker’s 185-pound frame, Adamson’s 200 pounds and Bartek were wedged into a usable area measuring 9 feet by 5 feet. The two-man raft had an inside measurement the size of a small, shallow bathtub.

As Rickenbacker put it: ‘Whenever you turned or twisted, you forced the others to turn or twist. It took days to learn how to make the most of the space, at an incalculable price in misery. A foot or hand or shoulder, moved in sleep or restlessness, was bound to take the raw flesh of a companion. With the flesh, tempers turned raw and many things said in the night had best be forgotten.’

The second orange was divided and distributed on the fourth morning, the second time the men had eaten in 72 hours. The sharks and hundreds of small fish swimming around the rafts ignored the bare hooks as well as those baited with orange rinds. Whittaker fashioned a spear out of one of the oars, but one attempt at impaling dinner did more damage to the spear than to the shark, so that project was abandoned.

At first, Cherry and Adamson sat all day with loaded revolvers, hoping to spot a seagull, but none came close enough for a shot. After a few days, however, the saltwater had rusted the pistols so badly that the men tossed them overboard.

The last two oranges by then had begun to deteriorate because of the saltwater, so the men had the third one on the fifth day and the last one a day later. Soon after the last of the fruit was gone, the men’s mood became deeply somber. At that point it seemed they would need a miracle to save them. They held prayer meetings and sang hymns to keep their spirits up. On the eighth day, events took a dramatic turn. After the afternoon prayer service, Rickenbacker was lying on his back with his hat pulled down over his face when something landed on it—a seagull. Rickenbacker slowly reached up, clamped his fingers around the gull’s legs and held on tight, then wrung its neck and stripped its feathers. He carved it up, divided the meat into equal shares and kept the intestines for bait. It did not matter to the men that the meat was raw and tough and tasted fishy. They ate all of it, including the bones.

When Cherry used the bait on a hook, a small mackerel grabbed on almost immediately. Rickenbacker then hooked a small sea bass. They ate one of the fish that afternoon and the other the next day. That cool, wet meat helped abate the men’s water craving. Spirits soared, and they began to believe they might manage to survive indefinitely with the abundance of fish, which had suddenly become easy prey.

Late that same afternoon the sky turned cloudy, the wind took on a different feel, and for the first time the prospects for rain looked promising. The men tried to remain awake after dark so they would be ready. It became so dark they could hardly keep track of the rafts. About 3 a.m. raindrops fell for a few minutes, and they spotted a squall not far away. They paddled toward it, praying they could get in its path. There was already a plan in place for such an occasion: They would catch rain on handkerchiefs, shirts and socks spread out over the rafts — Adamson even removed his shorts. The squall turned into a driving rainstorm, and all hands did what they could to collect water. Rickenbacker was designated his raft’s wringer; as the clothing became soaked, he twisted the water into a bucket.

After the storm subsided, the men agreed to ration the water sparingly: a half-jigger per day per man. It was the sweetest water they had ever tasted. The rain had also drenched their bodies and sores, cleansing much of the salt brine that had collected. However, Kaczmarczyk’s condition continued to deteriorate. Adamson, too, was suffering more and more, and Reynolds began to fade.

The winds suddenly grew much stronger, tossing the rafts around like so many corks and causing them to bump into each other, frequently drenching the men with the cold water. Rickenbacker asked Bartek to change boats with Kaczmarczyk so that Rickenbacker could hold the sergeant tight to help keep him warm. It seemed to help; Kaczmarczyk stopped shivering and began to sleep.

A couple of days later, Kaczmarczyk asked to rejoin De Angelis. Several men assisted in the transfer, realizing that the end was near for the young man. During the early morning hours of the 13th day he heaved a long sigh — his last breath. Upon Rickenbacker’s insistence, the group waited until daylight before making a final decision, to be absolutely certain he was gone. They removed Kaczmarczyk’s wallet and identification tag and then rolled his body over the side. It disappeared after a few minutes.

When all the drinking water was gone, their thirst became more and more intense. The men even experimented with saving their urine, hoping the heat and air would somehow distill it enough so that they could drink it. That did not work. It had been three days by then since they had finished off the fish. Sharks were always present in large numbers, swimming so close that they were continually bumping into the boats. Cherry caught a baby shark, stabbed it, cut it into small pieces and passed it around to the men. But the meat turned out to be tough and too smelly to eat. They tried curing it in the sun and everything else they could think of, but nothing worked. Even starving men had limits on what they would eat. The seawater, meanwhile, continued to take its toll. All the men suffered from salt sores that began with a rash affecting their legs, thighs and bottoms. Watches stopped working, the compass needle froze. Rickenbacker’s secret orders from Stimson faded out, and his map stuck together at the folds. Most of the items were of little use, however, because no one knew where they were, and time seemed irrelevant.

Rickenbacker had with him three St. Christopher medals and a crucifix that he had received from the young daughter of a friend before he left for Europe in World War I. He was not a Catholic and had never associated the items with good fortune. Nevertheless, he could not entirely dismiss the possibility that his fate was somehow involved with them. Another prized possession was a watch given him by the city of Detroit after World War I.

Rickenbacker’s concern for Adamson grew deeper by the day. His strength was ebbing away, his clothing was rotting and his eyes were bloodshot and swollen. One night Rickenbacker awoke and realized Adamson had somehow fallen overboard and was struggling a few feet away. Cherry and Whittaker helped Rickenbacker pull Adamson back into the raft.

The next morning Rickenbacker and Adamson reminisced at length about their association, which spanned several decades. After that session, however, the colonel seldom talked to anyone. The mood on the rafts changed drastically in the days that followed. The men made unusual demands, cursed each other and became wrathful because their prayers were not being answered. Even so, they drew the rafts together as usual each evening for prayer and the reading of scripture from Bartek’s fading Bible.

Rickenbacker tried everything to keep the men going. When sympathy proved ineffective, he would lash out with criticism — anything to prod them not to lose faith. One of the men called him the meanest and most cantankerous SOB he had ever known. Several of the men, Rickenbacker later learned, had sworn an oath that they would continue living, hoping for the pleasure of burying him at sea. Rickenbacker believed that all would be forgiven if, or when, they reached land. He never gave up hope of rescue, holding fast to his opinion that they were hundreds of miles north and west of convoy and air-ferry routes. The men made numerous attempts to row to the southeast, but prevailing tides and winds were against them.

While steadfast in his belief that the best chance for survival was to keep the rafts together, Rickenbacker finally agreed that it was time to try something different. The raft carrying the three strongest men would attempt to override the prevailing current and head to the southeast, hoping to be sighted by a transport plane or ship. Cherry, Whittaker and De Angelis volunteered and set out. Early the following morning Reynolds helped Rickenbacker stand up to look around, and they spotted the raft a short distance away. On their return, Cherry reported that the current and breeze were simply too much to overcome.

Although their latest gamble was a failure, intermittent squalls the next few days brought more drinking water. Rickenbacker came up with the idea to empty the carbon dioxide stored in his Mae West life jacket and replace it with water. Taking a mouthful, he forced it through a narrow tube into the jacket compartment. Although it took quite a while, he managed to store a quart of water.

The lack of food continued to be a problem. Fortune smiled again during one very dark night when a pack of sharks chased a school of mackerel through the three-raft convoy. Two of the fleeing fish landed in the rafts, were captured and promptly eaten. It was the first food in nearly a week.

Late in the afternoon of the 17th day, Cherry stood up and cocked an ear. Suddenly all the men saw what Cherry had heard: a monoplane aircraft with pontoons about five miles away flying low and fast in and out of squalls. Several of the men stood up, waved their arms and yelled even though they were too far away to be heard. Although it was clear they had not been spotted, the airplane was a great stimulus, the only sign of human life they had seen in more than two weeks. It meant either that land was in the vicinity or there was a ship nearby capable of launching an airplane. Most of the men were too excited to sleep that night, so they talked until they were exhausted.

The next afternoon they spotted two airplanes flying together several miles away. The men waved their shirts (the flares had been expended), but to no avail. They saw four more planes on the morning of the 19th day — two to the north and two to the south at about 4,000 feet. Once again attempts to signal them proved fruitless. No planes were sighted the next day, but a fair amount of food appeared when hundreds of small sardinelike fish swam by. The men captured a couple dozen of them, which meant they could enjoy sizable portions of both food and water.

Late in the afternoon of day 20, Cherry announced he wanted to man the small raft and try to find land. After much arguing back and forth among the men, Rickenbacker finally agreed to let him try, even though he felt it would be hopeless, believing that one raft would be more difficult to see than three. Since the planes had come from different directions, Cherry had no idea which way to head. De Angelis transferred to the lead raft, and Cherry drifted away with his Mae West full of water. Whittaker and De Angelis announced a short time later that they, too, wanted to try it on their own. Reynolds, who was also in their boat, was too sick to be aware of anything. They had concluded there was nothing to be gained by staying together. Rickenbacker did not agree with them, but when he realized the men would not change their minds, he acquiesced. The two rafts disappeared from sight by nightfall, leaving Rickenbacker alone with two very sick men: Adamson and Bartek, both of whom were barely alive. They had only about 2 1/2 quarts of water and no food.

On the morning of the 21st day, Rickenbacker poured a jigger of water for each, but neither Adamson nor Bartek could raise his head to drink. Rickenbacker successfully scooped up several small fish, but his strength, too, was ebbing. It seemed unusually hot, and Rickenbacker kept looking for a sign — any sign — that might indicate land was in the vicinity. There was none. Not even a gull. Bartek became alert enough to ask if any more planes had been seen, but when the answer was negative, he uttered something about there never would be any before lapsing back into a semicoma.

A short time later, however, Bartek muttered that he heard planes—and he was right. Two floatplanes were approaching from the southeast. Rickenbacker, the only one with enough strength, waved his old hat as hard as he could, but the aircraft disappeared to the west. He knew darkness would arrive soon and probably eliminate any chance of being found. Lady Luck was with them, however: A half-hour later the two planes returned and headed straight for them. The planes were low enough that Rickenbacker could see the pilot in one of them smiling and waving a hand. He was overjoyed to find that the aircraft belonged to the U.S. Navy.

After making a full circle around the raft, both planes headed away. The sun would soon be setting, and a squall had appeared to the south. Rickenbacker was concerned. (He later learned that the planes had left temporarily because they were getting low on fuel.)

About an hour later both planes reappeared, descended to a low altitude, and as one of them left the scene the other circled above, causing Rickenbacker to wonder whether a rescue attempt would be made that night or if they would have to wait until daylight. He definitely did not want to spend one more night on the raft, and he doubted that Adamson would survive much longer without help.

Just as dusk was turning to dark, the pilot released a white flare and a minute later fired a red one. Rickenbacker realized that he was signaling a ship, which soon appeared on the southern horizon, blinking a code signal. The pilot began a short glide and settled down on the water not far from the raft, taxied over and killed his engine. As Rickenbacker grabbed hold of the plane’s pontoon, the fliers climbed out on a wing and introduced themselves: pilot Lieutenant W.F. Eadie of Evanston, Ill., and radioman L.H. Boutte of Abbeville, La. They reported that a PT-boat was en route to pick up the men in the raft. Since Japanese were in the area, they did not want to signal the boat with additional flares. Instead, they decided to load the three survivors on the plane and taxi toward the vessel.

The pilot broke the good news that Captain Cherry had been sighted the day before about 25 miles away by a Navy plane on a routine patrol mission. Boutte had also been the radioman on that plane and had spotted Cherry’s raft. A nearby PT-boat picked up Cherry, who gave general directions to where Rickenbacker’s boat would be. In the meantime, a radio dispatch reported that three men had been located on an uninhabited island in that area. That would likely be Whittaker, De Angelis and Reynolds, and a doctor already had been dispatched to the island. Rickenbacker and his mates were the luckiest of the group, since their craft had drifted into the open sea, hundreds of miles from the next chain of islands. Rickenbacker estimated that during their 21-day marathon they had traveled perhaps 400 or 500 miles and across the international dateline. If so, it was now November 12, not the 11th.

After Adamson was lifted into the cockpit, Rickenbacker thought that he and Bartek would be left behind to await the rescue ship. But that was not to be the case—the crew secured Rickenbacker to one of the wings and Bartek to the other, then taxied toward the vessel that was heading in their direction. With their legs dangling off the leading edges of the wings, Rickenbacker and Bartek survived a wild half-hour ride in pitch dark to the rescue vessel.

After much discussion, the boat skipper, Lieutenant Eadie and Rickenbacker decided that Rickenbacker and Bartek would be taken aboard the boat, but that Adamson needed to continue on to an island base 30 miles away as he was in no condition to be transferred twice—onto the boat and then again at the island.

On the ship, blankets and bedrolls were ready for them. Bartek immediately fell asleep, but the excitement during the previous hour left Rickenbacker wide-awake. Three weeks of inactivity in cramped quarters had rendered his legs weak and wobbly, and he had to hold onto things when he made his first attempt to walk to the ship’s head.

When they arrived at the island base, Rickenbacker and Bartek were finally on solid ground—the answer to their prayers. A short drive down a lane between beautiful palm trees under a full moon to a small hospital climaxed a memorable day. The hospital was a one-story structure with fewer than a dozen cots and no air conditioning. Despite his demand for more, Rickenbacker was allowed only two ounces of water every two hours that first night. During that night Rickenbacker craved water more than at any time during his long ordeal at sea. It was one of the most uncomfortable nights he had ever experienced. The sunburn and sores that covered most of his body, even though they had been treated with healing compounds, hurt worse than during all his days on the raft. He had nightmarish dreams and woke frequently in a confused state. This was not the blissful experience he had envisioned while adrift. Cherry arrived the next day, and Navy tenders brought Whittaker and De Angelis a day later. Reynolds’ condition was so poor that they did not want to move him.

Whittaker and De Angelis described their harrowing experience. The day after they set out alone, they sighted palm trees and made for an island. When they made it to the beach, the two of them, too weak to stand, crawled on their hands and knees, dragging Reynolds across the sand. They found rainwater to drink and killed a rat, eating it raw. Then natives arrived by canoe and took them to a nearby island where an English missionary treated them until a Navy tender picked them up.

That afternoon a flying boat flew five of the men to larger medical facilities on Samoa. Too ill to be moved, Bartek and Reynolds remained on the tender. Adamson was moved only because his condition required the additional care available at Samoa, a decision that probably saved his life.

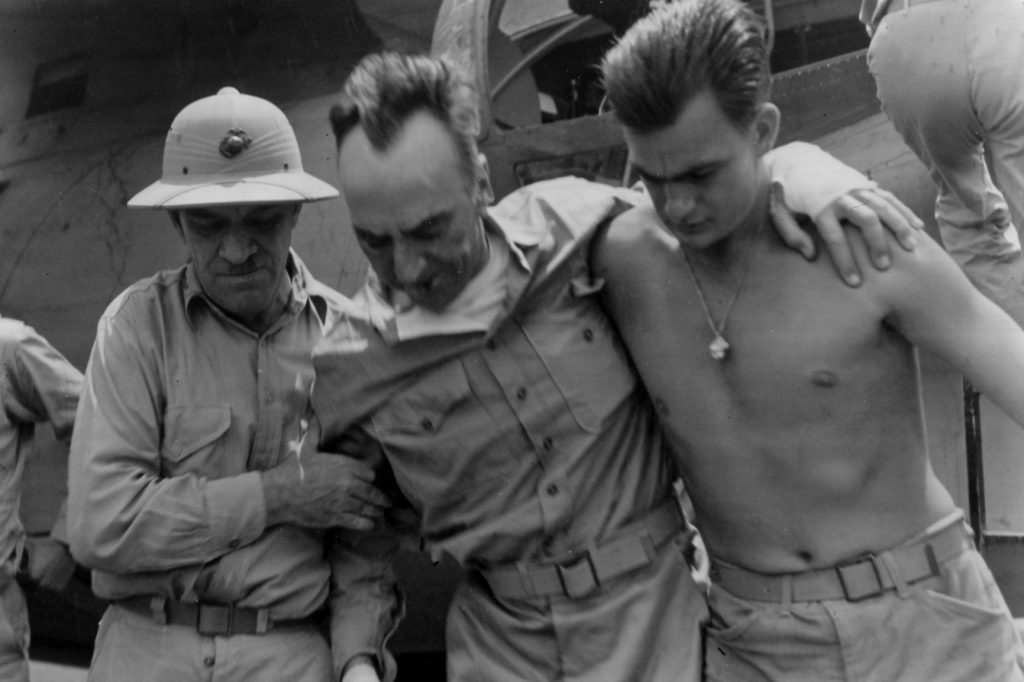

At the hospital all the men except Adamson were soon making a satisfactory recovery, and Rickenbacker wired Secretary of War Stimson that he expected to be well enough to continue his mission in about two weeks. General Arnold sent word that he would send a plane from the United States as soon as Rickenbacker was ready.

After two weeks of drinking gallons of fruit juice and eating everything placed before him, the man the Boston Globe called ‘The Great Indestructible’ was feeling great, had regained half of the 40 pounds he had lost and told General Arnold that he was ready to go. Before leaving, however, Rickenbacker had to break the news to Adamson that he would have to stay behind, but promised to pick up his aide on the way back home. Bartek had arrived at Samoa looking quite frail but well on his way to recovery. He reported that Reynolds was out of danger but still too ill to be moved.

The plane, piloted by Captain H.P. Luna and a crew of six, took off at sunrise on December 1 for Brisbane, Australia. After the first day, much of the flying was done at night so that Rickenbacker could visit island air bases during the day.

At Brisbane he visited with Australian military officials, then boarded an armed B-17 and flew to Port Moresby, New Guinea, to visit General Douglas MacArthur’s headquarters and spend time with Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, commander of the Fifth Air Force, Brig. Gen. Ennis C. Whitehead and Brig. Gen. Kenneth N. Walker. In the course of his stay, Rickenbacker had many eye-opening discussions with the generals who were directing action against the Japanese.

On the way back to Brisbane, they stopped at several bases before Rickenbacker boarded a Consolidated B-24 and headed for Guadalcanal, where he learned much about combat conditions that would prove beneficial to Washington. From Guadalcanal, Rickenbacker stopped in Samoa before heading for home.

On Samoa, he visited Adamson, who had suffered a relapse. He recovered quickly, however, and soon was fit enough to make the trip home accompanied by his physician.

Before leaving Samoa, Rickenbacker received the good news that Reynolds, though very thin and weak, would also be allowed to return home with them. They left on December 14, dropping Reynolds off at his hometown of Oakland and stopping by Los Angeles so that Rickenbacker could visit his mother before the final leg to Bolling Field at Washington, D.C. They arrived on December 19, exactly two months from the day they had left San Francisco.

A large group greeted them at the airport, including Robert Lovett, assistant secretary of war for air; General Arnold; Maj. Gen. Harold George, chief of the Air Transport Command; and other high-ranking officials—as well as Rickenbacker’s wife, Adelaide, and sons, David and Billy, and Mrs. Adamson.

A portion of Rickenbacker’s mission report to Stimson and General Arnold included practical suggestions for survival equipment—including a sheet to cover rafts and collect rainwater and saltwater distilling kits. There is no doubt the recommendations came from a man with real-life experience.

This article was written by Billy A. Rea and originally appeared in the February 2004 issue of World War II magazine.

For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!