Legendary lawman Wyatt Earp and family associated with an assortment of Western characters before, during and after their tumultuous time in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. The long list of fellow sophisticates includes such notable gunfighters/lawmen as Bat Masterson and brothers, Doc Holliday, Bill Tilghman, Fred Dodge, Luke Short, “Buckskin Frank” Leslie, “Rawhide Jake” Brighton, Bob Paul, Jim Leavy, John Behan, Clay Allison and John Ringo. But they befriended plenty of others outside that circle, from writer Jack London to film star William S. Hart, boxing promoter “Tex” Rickard, businessman “Lucky” Baldwin, mining investor George Hearst and oil man Ed Doheny. The Earps’ ties to such noteworthy figures deserve a deeper look.

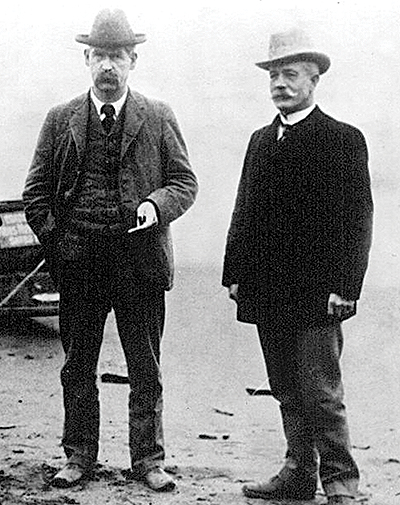

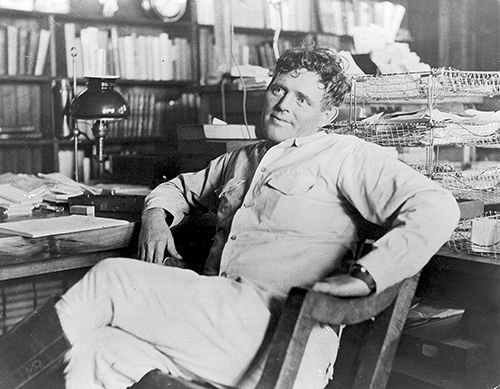

Any discussion of Earp connections should begin with a mention of prolific Western diarist George Whitwell Parsons (at top, second from left), who wrote extensively of his time in Tombstone during the Earp era. By the late 1880s Parsons was well established in Los Angeles, where he became a Chamber of Commerce kingpin, headed several mining information bureaus, was active in church affairs, served as an officer in and president of the Southern California Academy of Sciences and spearheaded a campaign to signpost water sources in the desert. In an era when influential individuals were pressing for Santa Monica to become the Los Angeles area port city, Parsons advocated preservation of that picturesque ocean resort. Due in part to his tenacious efforts, San Pedro wound up with the port facilities. He was an admirer of Wyatt Earp from their Tombstone days and remained so when the famed lawman moved to Los Angeles with common-law wife Josie. He commented broadly on the Earps in his six decades’ worth of diaries. Little wonder he was a pallbearer at Wyatt’s 1929 funeral. Parsons stopped keeping a diary that year.

Most mentions of Wyatt in the two decades after Tombstone originate from San Diego and San Francisco, where he engaged in his usual pursuits—gambling, mining, horse racing and the sporting life in general. But as family members settled in Colton and San Bernardino, and Wyatt, Virgil and James followed the boxing and horse racing circuit, the brothers—and sometimes father Nicholas—found themselves increasingly drawn to Los Angeles.

There is no telling how often these fellows may have met, even in passing, in Los Angeles. Hints suggest encounters at the Agricultural Park horse racing grounds

Several prominent personalities with Tombstone ties had assumed leading roles in Los Angeles’ affairs. Albert Bilicke was operating the downtown Hollenbeck Hotel (billed as the “Headquarters for Arizonans”), while Remi Nadeau erected L.A.’s first four-story building (the Nadeau Hotel, which also boasted the first elevator in town). Operating the restaurant at the Nadeau was Hyman Solomon. The trio had already made their mark in Tombstone.

In the tense wake of the O.K. Corral shootout Bilicke’s Cosmopolitan Hotel served as the Earps’ emergency headquarters, and the family later held murdered brother Morgan’s funeral ceremonies there. In quieter times Bilicke and Earp had consummated mining deals in the same building. In April 1882, after the Earp/Holliday party had left Tombstone on their vendetta ride, the Cosmopolitan welcomed General William Tecumseh Sherman, who had replaced Ulysses S. Grant as commanding general of the Army in 1869 after Grant was elected president. Local dignitaries, including Tombstone Epitaph editor John Clum, attorney Ben Goodrich and Oriental Saloon owner and local politico Milt Joyce, wined and dined the general at Bilicke’s hotel. Sherman’s Tombstone visit and territorial inspection tour is detailed by diarist Parsons, whom the general personally invited to accompany him to Fort Huachuca. On May 7, 1915, Bilicke was a passenger aboard RMS Lusitania when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the British ocean liner—one of the events that precipitated World War I. He was killed, while his wife survived. Nadeau, a leading freighter in the region, had purchased mining property in Tombstone from the Earps. Solomon, a merchant and member of the Tombstone Common Council and Cochise County Board of Supervisors, had presented a Winchester to the rifleless Holliday as the Earp party left town on their vendetta ride.

There is no telling how often these fellows may have met, even in passing, in Los Angeles. Hints suggest encounters at the Agricultural Park horse racing grounds. In July 1890 one of the races was dubbed the Nadeau Handicap, while entered in other races were mounts belonging to both Wyatt Earp and Lou Rickabaugh, a former partner of Wyatt’s in the gaming concessions at Tombstone’s Oriental Saloon. The following month the track featured the running of the Hollenbeck Stakes, and the onetime saloon partners had horses in races.

Nadeau himself had died in 1887, leaving middle son George in charge of his business concerns, including a namesake racetrack, primarily a practice area for trotters. Another Nadeau holding that would have interested the Earps was the area’s largest winery and newest distillery.

The Curtis family of San Bernardino must have encountered Earps many times over the half century ending in 1930. In 1864 they joined the California-bound caravan led by cantankerous Nicholas Earp and family, a trek documented in the diary of fellow traveler Sarah Jane Rousseau. The Earps and Curtises don’t appear to have been social intimates in San Bernardino County, but they moved in similar circles. Nicholas served as justice of the peace and Virgil as chief of police in Colton, while James ran a San Bernardino saloon. Around the same time William Jesse Curtis, the patriarch of his family, served as district attorney of San Bernardino County. His son Jesse succeeded him as district attorney and later served on the California Supreme Court.

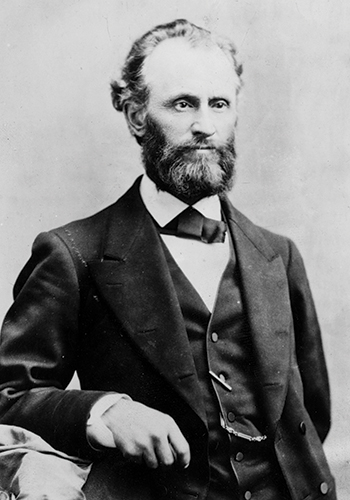

The Earps doubtless encountered other prominent Tombstoners in Los Angeles. Tombstone lumber dealer Lewis W. Blinn became the lumber king of southern California, with 40 yards in the region, and also had banking interests in Los Angeles and San Pedro with Parsons. Dr. George E. Goodfellow, who tended to the Earp brothers’ assorted wounds in Tombstone, lived and traveled in the Los Angeles area and died in town in 1910. Tombstone attorney Goodrich—who had represented Ike Clanton as a prosecutor in the 1881 post–O.K. Corral gunfight “Spicer Hearing” and served in the Arizona Territorial Legislature—later bounced between Tombstone and Los Angeles, where he was the attorney of choice for the mining empires of Eliphalet Butler Gage and Colonel William C. Greene.

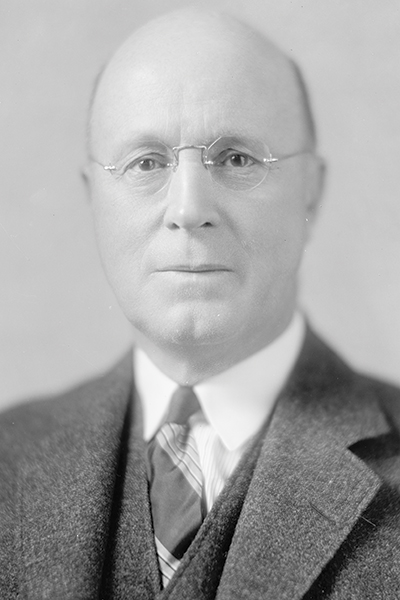

Attorney William J. “Will” Hunsaker, who practiced law in Tombstone when the Earps were in town, served as mayor of San Diego in 1888 and was a leading figure in California legal circles, eventually becoming president of the California Bar Association. He was a pallbearer at Wyatt’s funeral (see photo at top of post), and until Hunsaker’s own death in 1933 Josie took her personal and financial issues to him—probably too often, as it is doubtful he would have allowed her to pay for his services. Tom Fitch, a leading figure in the O.K. Corral hearings, also lived in Los Angeles for years but doesn’t seem to have had much contact with the Earps.

According to Josie, rancher Henry Clay Hooker, who retired to Los Angeles and died there in 1907, “was in touch with Wyatt for years after he left Tombstone and was one of his best friends.” Hooker’s former daughter-in-law Forrestine promised Wyatt she would “tell the world” of his importance, but only a flabby manuscript resulted.

Former Tombstone Epitaph editor Clum moved to San Bernardino in 1886, where he dabbled in real estate and intermingled with the Earps. He later encountered both Wyatt and Parsons while serving as a postal inspector and postmaster in Alaska from 1898 to 1909. In 1928 Clum moved to Los Angeles, where he made sporadic visits to Wyatt. He spoke with Earp the night before his death and was a pallbearer at his funeral. Clum died in Los Angeles in 1932.

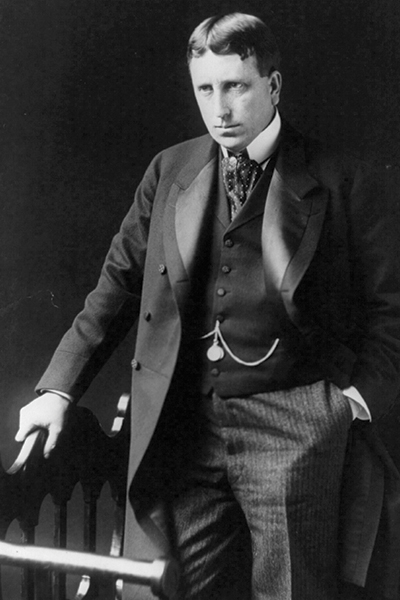

Wyatt first met George Hearst early in 1882 when Hearst was considering mining properties in and around Tombstone. Later, in San Francisco, when then U.S. Senator Hearst and son William Randolph Hearst were running the Examiner, Wyatt renewed their acquaintance. In 1903, when the Hearst newspaper empire opened an office in Los Angeles, it set up in the Bilicke Building, reasserting the old Tombstone connections.

The Baldwin-Earp affiliation spanned virtually the entire Pacific Coast. Wealthy real estate and mining investor Elias Jackson “Lucky” Baldwin was a headline-grabbing personality known for his namesake San Francisco hotel, his thoroughbred racehorses, his arrogance and his womanizing (he was twice shot by women, once in a courtroom drama). Lucky and Wyatt first met in San Diego racing circles in the 1880s and later in the Los Angeles racing world (Earp and Rickabaugh trained some of their horses on the Baldwin Ranch), as well as the racing-gambling world of San Francisco (negotiations for the 1896 Fitzsimmons-Sharkey fight, controversially refereed by Earp, took place at the Baldwin Hotel). In 1900 Lucky and Wyatt met over a few glasses at the Earp-run Dexter Saloon in Nome, Alaska. Wyatt, Josie and Lucky remained in contact in the Los Angeles area until Baldwin’s death in 1909.

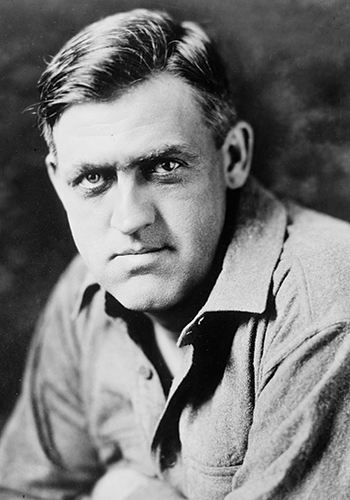

It is astonishing how many individuals destined for fame Wyatt and Josie met in Alaska amid the Klondike Gold Rush. Sid Grauman and Alexander Pantages of movie theater fame were there at the outset of their working lives, trying to make a buck by entertaining miners, and at best saw Wyatt dispensing drinks or sitting at a faro table in Nome. Others, like boxing promoter Rickard, would continue their relationships with Wyatt in Nevada and California. Although some say Call of the Wild author London first knew Wyatt in Alaska, they most likely didn’t meet until later in California.

Playwright, raconteur and serial entrepreneur Wilson Mizner (another pallbearer at Wyatt’s funeral; see top of post) spent many a tipsy evening with the Earps while snowed in for weeks in the boomtown of Rampart. Entertaining them was luckless prospector Rex Beach on his mandolin (Josie called it a banjo). Beach had better fortune as a novelist, his best-selling saga of Nome, The Spoilers, being adapted for the stage and screen, including five films. Also associating with Wyatt and Josie in Rampart and Nome were U.S. Marshal Cornelius L. Vawter and wife Sarah. Marshal Vawter was among the principal figures in the Nome gold claim swindle, a central plot device of The Spoilers. Coincidentally, he was also related to Williamson Dunn Vawter, an influential pioneer of both Pasadena and Santa Monica.

Among others snowed in with Wyatt and Josie in Rampart were Washingtonians John Harte McGraw and Eugene M. Carr, who were working neighboring gold claims and often socialized with the Earps. McGraw had recently served as the second governor of Washington state and was a former sheriff of King County, while Brig. Gen. Carr had stepped down as head of the Washington National Guard to join the gold rush.

The list of Californians in the Earp orbit is particularly impressive. Associates from northern California included jockey Tod Sloan. He rode several mounts for Wyatt at San Francisco’s Bay District Track in 1895 and went on to become one of the most successful jockeys in the United States and Britain.

Southern Californians also figured into the Earp mix. By the early 1900s Los Angeles oil developer Edward L. Doheny was a millionaire many times over. He apparently entered the Earp fold via Virgil, whom he met in the late 1870s in Prescott, Arizona Territory, where Virgil served as a constable and stagecoach driver, and Doheny dabbled unsuccessfully as both a painter and prospector. In the 1920s Wyatt was a minor player in the Kern County, Calif., oilfields, which may have brought him into contact with the oil baron. Doheny grabbed headlines in 1922 when implicated (with Harry Ford Sinclair of Sinclair Oil) in the Teapot Dome Scandal. He was twice acquitted of having bribed New Mexico politico turned U.S. Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall for oil leasing rights, though Fall and Sinclair both served prison terms for their roles. Doheny and second wife Carrie garnered more headlines for their philanthropy in Los Angeles. They donated the land for Doheny State Beach, in Dana Point, Calif., the surfing strand celebrated in the Beach Boys’ 1960s hits “Surfin’ Safari” and “Surfin’ U.S.A.” When finances were strained, a widowed Josie Earp reportedly contacted Doheny to the point of pestering.

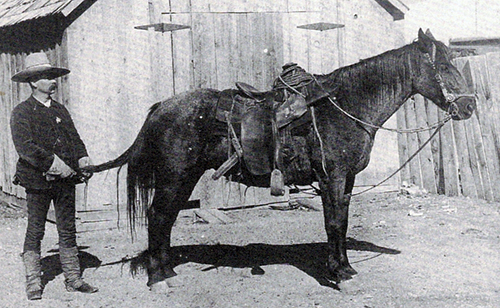

Tom Mix, among few genuine Western cowboys to have starred in films, was a known companion of the Earps and attended horse races with Wyatt and Josie. The couple’s primary Hollywood contact, though, was William S. Hart, the foremost Western star of the silent era. Hart met and corresponded with them frequently from his ranch north of Los Angeles. For years he urged Wyatt to pen his autobiography and have a realistic film made about his life. Mix and Hart both served as pallbearers at Earp’s funeral.

Richard “Dick” Gird—who made a fortune setting up the Tombstone mining district and went on to found Chino, Calif., in 1910—reconnected with Wyatt in the early 1890s through the Los Angeles horse racing circuit.

Not all former fellow Tombstoners in greater Los Angeles fawned over Earp, though. Historians have yet to establish any further interaction between him and mining executive Gage, miner/cattleman John Van Vickers or financier John Vosburg, for example.

One of the world’s most successful book publishers is on the list of Wyatt Earp acquaintances. Bookseller Alexander M. “Aleck” Robertson arrived in Tombstone in 1881, prior to the gunfight of O.K. Corral fame, setting up shop on Fifth Street between Allen and Fremont. Robertson became the publisher and close associate of such famed authors as London, Mark Twain, Bret Harte and Robert Louis Stevenson. In later years he hosted Earp, Parsons, Blinn, Buckskin Frank Leslie and other former Tombstoners in his massive San Francisco book emporium.

Born Nashville Franklyn Leslie, Buckskin Frank was a classic Western figure who at times worked as a Tombstone saloonman and faro player, government scout and prospector. A noted gunfighter, he killed a few folks (including a female paramour, for which he served six years in the Yuma Territorial Prison). On June 22, 1880, while living at Bilicke’s Cosmopolitan Hotel in Tombstone, Leslie shot down Mike Killeen. Days later he married Killeen’s widow, Mary, a chambermaid at the hotel. For the time they lived in town, Buckskin Frank and the Earp brothers saw each other almost daily.

You could say C.S. Fly knew the Earps up close, as his studio abutted the vacant lot behind the O.K. Corral—scene of the 1881 shootout. When the gunfight broke out, Ike Clanton hid in Fly’s studio, and the photographer personally disarmed Ike’s mortally wounded brother Billy

Other Earp associates from the Tombstone days became nationally prominent figures. On leaving Arizona Territory in 1898, restaurateur/hotelier/miner Nellie Cashman spent another quarter century as an entrepreneur, marked by notices in the mining journals as well as The New York Times. Tombstone City Marshal David Neagle—who with Cochise County Sheriff John Behan tried and failed to arrest Wyatt and Warren Earp, Holliday and their vendetta posse at the Cosmopolitan as they left Tombstone for keeps in 1882—later moved to California. In 1889, while serving as a bodyguard for a U.S. Supreme Court associate justice, Neagle killed a former California chief justice amid an assault by the latter. The Supreme Court eventually ruled in Neagle’s favor in a case with profound implications for the supremacy of federal law over state law. Photographer C.S. Fly, revered for his rare images of the frontier Southwest and Mexico, got his start in Tombstone. You could say Fly knew the Earps up close, as his studio abutted the vacant lot behind the O.K. Corral—scene of the 1881 shootout. When the gunfight broke out, Ike Clanton hid in Fly’s studio, and the photographer personally disarmed Ike’s mortally wounded brother Billy.

Six years later in Arizona Territory well-known Western lawman and detective Jonas V. “Rawhide Jake” Brighton sent Ike Clanton to an early grave. In 1893 the lawman had a leading role in ending the depredations of the Sontag-Evans gang in California. After 1900 Brighton served as a policeman and constable in the Sawtelle district of Los Angeles and its Old Soldiers’ Home, where he resided. He would have seen the Earps almost daily in Sawtelle, as James was running illicit booze, and father Nicholas and eldest son Newton also lived in the Old Soldiers’ Home. Corporal Brighton is buried beside wife Mary and not far from Sergeant Nick Earp in the Los Angeles National Cemetery (the former Sawtelle Veterans Cemetery).

A notable Earp associate with no ties to California was Key Pittman. He and Wyatt met in Nome, where Pittman prospected and served as the first city attorney. After leaving Alaska, both men arrived in the silver boomtown of Tonopah, Nev., in 1902. Pittman put down roots, serving as a U.S. senator from Nevada for almost 30 years. A notorious lush, the politico almost certainly patronized Nome’s Dexter Saloon and Tonopah’s Northern Saloon, both Earp operations.

There is more to the Nevada angle. Among the more influential Nevada politicians of the era was Tasker Oddie, one-term governor, two-term U.S. senator and a key figure in the rise of the Tonopah mining district. From his Washington office in 1928 Senator Oddie recalled that in those days “Wyatt Earp and 15 others of similar spirit were mustered to protect our claims from squatters.”

Another notable Earp acquaintance with no known California connection was the Rev. Endicott Peabody. He arrived in Tombstone in the immediate wake of the O.K. Corral fight, founded the historic St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and immersed himself in the community’s social and sporting circles. In later years he heaped praise on the Earp brothers for their roles in law enforcement. Peabody became a nationally known figure in education and officiated at the wedding of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (a former pupil of the reverend’s at Massachusetts’ prestigious Groton School for Boys, as were cousin Theodore Roosevelt’s four sons).

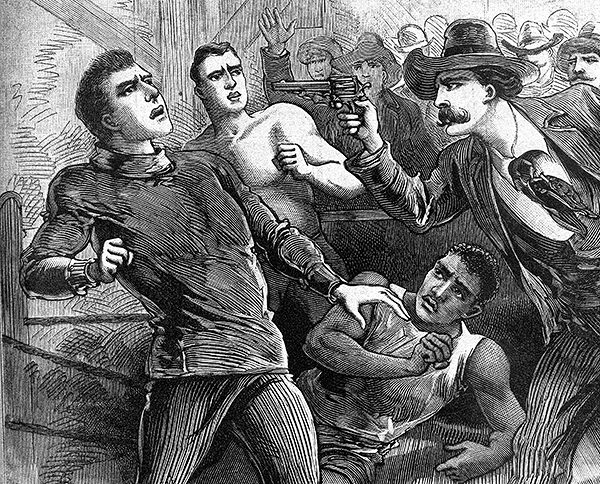

Another nationally known figure with Earp ties was boxing legend James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, a world heavyweight champion and future inductee in the International Boxing Hall of Fame. You could say Virgil Earp knew Corbett up close. As the story goes, Corbett was in San Bernardino in May 1892, giving an exhibition and observing other matches. In one such bout his sparring partner was being pulverized when Corbett intervened. Entering the ring, he proceeded to kick and otherwise abuse the challenger. Referee Virgil Earp told “Ungentlemanly Jim” to desist. Instead, Corbett yelled at and advanced on Earp. Bad idea. “Paralyzed by the sight of a big Navy revolver in the hands of Earp,” one newspaper reported, “Corbett very wisely did not strike.” The story made headlines coast to coast.

When refereeing the controversial 1896 Fitzsimmons-Sharkey bout, Wyatt Earp became all too familiar with Judge James G. Swinnerton and son Jimmy, a budding cartoonist at William Randolph Hearst’s Examiner. In the wake of the fight Judge Swinnerton was part of the cabal seeking to overturn Earp’s upset decision for Tom Sharkey over Bob Fitzsimmons. At the same time Jimmy was lampooning Earp with biting cartoons in the Examiner. Young Swinnerton went on to become a leading cartoonist for the San Francisco and New York papers. Indeed, some consider him the “father of the comic strip,” having drawn his first for Hearst in 1892. A close friend and favorite employee of the famed newspaper publisher (and Earp acquaintance), Jimmy later earned acclaim as one of the Southwest’s preeminent “Painters of the Desert.” He befriended fellow desert painter Victor Clyde Forsythe, whose parents and uncle were merchants in Tombstone in the early 1880s—contemporaries with the Earp brothers there and later in Los Angeles. In 1952 Forsythe painted a well-received, accurate depiction of the “Gunfight at O.K. Corral” based on his parents’ diaries.

In the sporting world of bookmakers and “plungers” (high-risk gamblers), Riley Grannan stood out from New York to San Francisco. Several Earps were familiar with Grannan. In the wake of the Fitzsimmons-Sharkey fight Grannan was among those who lambasted Wyatt’s decision in the press. Days after the bout Wyatt and brother James encountered Grannan at a local racetrack. An alcohol-fueled James cursed Grannan and demanded they shoot it out with revolvers. Apologizing for his brother’s outburst, Wyatt managed to defuse the situation.

One would have to search far and wide to uncover another family with such diverse, influential and historically significant Western connections. And to think the Earps would reconnect with many of them for one last hurrah in the early decades of the 1900s.

A frequent contributor to Wild West, Don Chaput is the author of Virgil Earp: Western Peace Officer and co-author with Lynn R. Bailey of Cochise County Stalwarts: A Who’s Who of the Terrritorial Years. His article “Clusters of Earps” appeared in the October 2020 issue. David D. de Haas’ Art of the West article about Victor Clyde Forsythe is online at Historynet.com. For further reading see the authors’ 2020 book The Earps Invade Southern California: Bootlegging Los Angeles, Santa Monica and the Old Soldiers’ Home (reviewed in the February 2021 issue and online at Historynet.com).