Many escaped slaves succumbed to an implacable new foe: smallpox.

On Christmas Eve 1862, Julia Wilbur, a freedman’s aid worker in Washington, D.C., wrote to her family in upstate New York: “Small pox ambulances may be seen in every part of the city. I think it is all over & all around us. The 19th Conn Regt is encamped a little west of us. An officer…told Mr. W[hipple] last night that 90 of their men had black measles, but we know when they talk about black measles, that it is very likely to be small pox….”

In an 1863 report to the Rochester (N.Y.) Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Wilbur wrote, “During the winter and spring, the small pox made dreadful ravages among the freed people. No measures were taken at first to prevent it, and it spread all over the city….Of the contrabands, we think about 700 died of the disease.”

John Williams, an African-American soldier in New Bern, N.C., supplied more chilling detail in an 1864 letter to a Union officer outlining the disparity in treatment of white and black victims: “I write to know if theire cant be some protection for the colored people of new Bern the people of coler when they are taken with the small pox they hae to be dragged across the river and their they have not half medical attendanc for them. It is said by the folks that has got well that they do not get enough to eat and when thy die thy have a hole dug and put them in without any coffin and I think this is a most horrible treatment and therefore thy ought to have some person that will look after them in a better manner then this[.] the[re] is A grat distinction made between the white and the colored in such cases as this when the whites are taken with this disseas thy taken care of and so you will pease to look into this matter.”

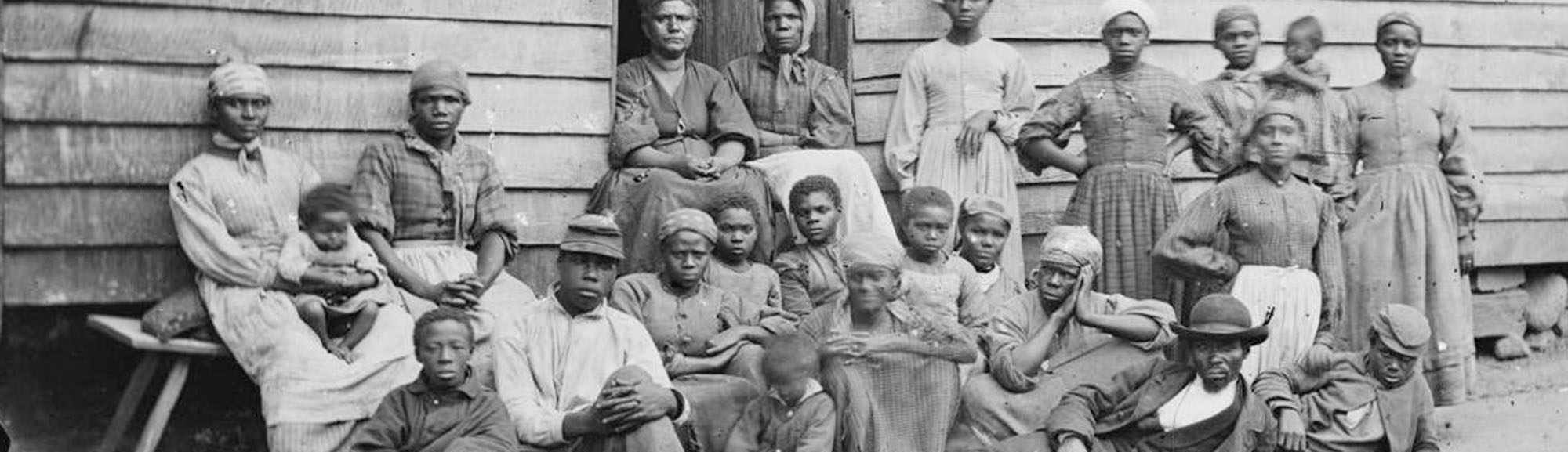

Vignettes like these tell the story of a smallpox epidemic that decimated the newly freed people. It began in Washington in the winter of 1862, spread to the Upper South in 1863-64, culminated in the Lower South and Mississippi Valley in 1865, and eventually seeped into the Western territories in 1867-68, infecting Native Americans. In the millions of documents that chronicle the battles of the Civil War and the coming of Reconstruction, there are no photographs of those suffering from smallpox. Instead, the dominant images of Reconstruction show hard-fought political battles won: large groups gathering under a banner of citizenship, and freedwomen singing about liberty. Virtually no sources describe what the epidemic meant for freed people during emancipation.

Smallpox broke out in 1862 in the nation’s capital, where wartime upheaval was promoting conditions for transmitting the virus, which spreads through air exhaled by an infected person and by contact with an infected person, bedding or clothing. The Union troops were assembled in makeshift quarters, and freed slaves were flooding into squalid settlements known as “contraband camps.” The city was in a panic. While wealthy Washingtonians were vaccinated two to three times to ward off being infected with the full-blown deadly virus, city officials scrambled to develop a procedure to vaccinate all the city’s school-age children. Some freed slaves dosed their bodies with tar to ward off possible infection. The metropolitan police requested that the army remove the bodies of former slaves who died of smallpox and were left on city streets. Letter-writers from the capital warned travelers and passersby to avoid the area at all costs, and yellow flags were hung throughout the city to signal the presence of the “deadly scourge.”

While military officials ordered some former slaves to recross the Potomac to live in prisons and former slave pens in Alexandria and Fortress Monroe, others were left on their own. After a snowstorm struck the city, followed by rain and icy cold temperatures, former slaves were forced to find shelter on frozen or muddy streets. With few options available to them, many former slaves congregated in overcrowded tents in the center of Washington, D.C.

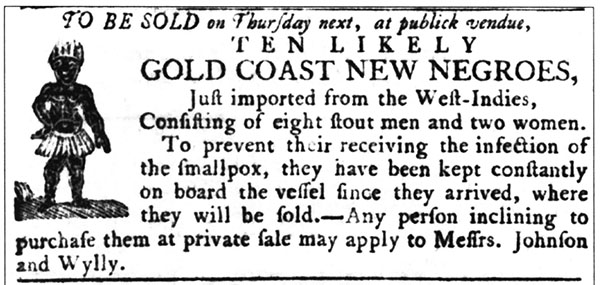

Ironically, smallpox was a virus that local governments and doctors had been battling since the 18th century, yet when it broke out among emancipated slaves, federal officials failed to follow the protocols and procedures—vaccination, and quarantine where necessary—that doctors and communities had implemented for decades. They seemed to regard the outbreak among freed people as a “natural outcome” of emancipation, which only reinforced theories that newly freed black people were on the verge of extinction. From that point of view, officials had little incentive to try to stop its spread. Instead, they propagated a medical fiction that smallpox was a disease limited to former slaves—despite advances in 19th-century medicine that underscored environmental factors as the cause of the virus’ transmission.

According to the Medical Society of Washington, building barracks to house former slaves would have prevented the outbreak of smallpox in the first place. In their report on health conditions during the war, published in 1864, local physicians condemned military officials for not building barracks for freed people on the outskirts of town or in the city’s vacant lots, forcing them instead to congregate in overcrowded camps in the center of town, which was filled with trash, excrement and rotten food. “It is generally admitted,” the physicians posited, “that small-pox is one of the diseases due to domiciliary circumstances, and is at all times a preventable disease. It has been stated over and over again by eminent authorities, that there need not be a single case of small-pox in any city; if the authorities will but take the proper steps to check it.”

Sadly, the authorities in Washington were too late. The effort of the Freedmen’s Bureau to establish the newly freed people as workers was spurring massive migrations across the South. By 1864 the virus was cropping up throughout the South. Describing his experience in Hilton Head, S.C., in 1864, a freedman recounted the initial symptoms of a smallpox infection: “We tuck down wid feber…’case we hasn’t got nuttin’ for keep warm.” In one colony in Hilton Head where former slaves took refuge, smallpox killed freed people by “tens and twenties.”

As one Freedmen’s Bureau official noted in 1864, “In country parishes where vaccination is not the custom, with no physician near, where the colored children are poorly fed and clad, and much exposed, they sicken, die, and are buried, without a record of their numbers.” The Christian Recorder added, “You may see a child well and hearty this morning, and in the evening you will hear of its death.”

By early autumn of 1865, the virus reached Washington, N.C., and infected well over 300 freed people in one week. In the Sea Islands, where former Confederate doctors joined the fight to halt the virus, it killed roughly 800 freed people a week in November and December. Yet in the fall of 1865, when Bureau physicians began to report the increasing cases of smallpox, neither the Freedmen’s Bureau nor the medical profession classified smallpox as an epidemic. James E. Yeatman, president of the Sanitary Commission, recognized the need for the government to declare an epidemic when he arrived at Camp Benton, Mo. He explained to military authorities, “Small-pox has had its appearance at several posts and in one of our hospitals; every precaution has been taken to prevent it from spreading, but, in order to arrest and mitigate the horrors of this dreaded disease it is necessary that some obligatory order be issued to colonels of regiments, holding them responsible for the prompt execution of the same.” Military and government leaders failed to enact a similar order for the freed people.

Even basic food and supplies could not be counted upon, let alone coordinated medical care. When the smallpox epidemic hit the area surrounding Raleigh, N.C., in February 1866, two freedwomen “walked twenty-two miles” in search of rations and support. The unexpected cold weather, combined with the outbreak of smallpox in the state capital, had depleted the bureau’s supply reserve. After discovering that even the benevolent office had “only empty barrels and boxes,” and “nothing of real service to offer,” the women wept.

Not until May 1866 did the outbreak begin to show signs of slowly dissipating. Bureau records indicate that the number of infected freed people dropped from 135 cases a week to about 40 cases.

By 1869, the chairman of the Committee of Freedmen’s Affairs estimated that smallpox had infected roughly 49,000 freed people throughout the postwar South from June 1865 to December 1867. This statistic tells only part of the story. Records of Freedman Bureau physicians in the field suggest that the numbers in their specific jurisdictions were, in fact, much higher. In the Carolinas roughly 30,000 freed people succumbed to the virus in less than a six-month period in 1865. From December 1865 to October 1866, when the epidemic reached its peak, bureau physicians in Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina and Virginia estimated that hundreds of freed people a month became infected with the virus. Due to the countless freed people in need of medical assistance, many bureau doctors claimed to be unable to keep accurate records. “I am unable to forward the consolidated reports of the sick freedmen for the month of February,” wrote a Bureau doctor from North Carolina.

One of the most poignant accounts comes from Harriet Jacobs, a former slave turned author who headed to Washington in 1862 to help in the contraband camps. She told abolitionist William Garrison that the sick and dying freed slaves, unlike ailing soldiers, had no chaplains or nurses to comfort them— that they looked at her with “tearful eyes” that asked “is this freedom?”

Adapted from Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction, by Jim Downs, Oxford University Press (2012). Downs teaches at Connecticut College.

Originally published in the June 2013 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.