As France and Spain vied for the key port of Dunkirk in early 1658, England unexpectedly held the balance.

THE SHIFTING SANDS AND BRACKISH TIDES SURROUNDING THE PORT of Dunkirk were no less treacherous or unpredictable than the murky political alliances on display there in June 1658. Two bristling armies, each commanded in whole or in part by a storied French general and variously including large contingents of French, English, Spanish, Swiss, German, and Walloon troops, jockeyed for position around the besieged city. Even the city’s ownership was in dispute. Although Dunkirk was technically in France, Spain claimed it as part of its northernmost colony, the Spanish Netherlands. A decade earlier, Spain and the Dutch Republic had concluded an uneasy peace settlement that gave the Dutch their independence but allowed Spain to retain the southern half of the Netherlands. Neighboring France, ruled by the regent Queen Anne in the name of her underage son, King Louis XIV, looked on the new arrangement—particularly Spanish control of Dunkirk—with scant enthusiasm.

But the French rulers had more immediate problems than the disposition of Dunkirk or the Netherlands. A series of spontaneous rebellions known collectively as La Fronde (after the slingshots rebels used during the first round of rioting in Paris in 1648) had kept the nation in a near-constant state of turmoil. Less a spontaneous people’s revolt than a reassertion of hereditary rights by French noblemen aggrieved by the crown’s steady accumulation of power, the three Fronde wars featured an ever-changing roster of pro-royal and pro-rebel commanders. Not even the principals could keep track of all the changes. Leaders switched sides at a moment’s notice.

The commander of the royal forces, Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne, had initially opposed the king and been imprisoned during the First Fronde War before repenting and being restored to command. At age 46, Turenne was one of the most respected generals in Europe. He had served in the Eighty Years’ War and the Thirty Years’ War—the names alone were stark evidence of the European propensity for conflict—and had subdued Bavaria and its faithless Elector (prince of the Holy Roman Empire), Maximilian I, at the Battle of Zusmarshausen in 1648. A French Protestant, or Huguenot, Turenne had entered the military at 14 and risen rapidly to command, overcoming not only his minority religion but also a lifelong speech impediment. By age 32 he was a full-fledged marshal of France.

Turenne’s rebel counterpart, Louis II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, was almost exactly 10 years younger than Turenne. A blood relative of Henry IV, the late king of France, he had been forced while still a minor to marry the 13-year-old niece of the all-powerful cardinal Armand de Richelieu. (He eventually locked her away in the countryside after claiming, improbably, that she had committed adultery with numerous men. The princess, by all accounts, kept her marriage vows—and was also notoriously homely.) One of the richest men in France, with hereditary holdings that included the lush provinces of Burgundy and Lorraine, Condé had become a general at 21 and, alongside Turenne, his later opponent, won significant victories during the Thirty Years’ War at Rocroi, Freiburg, and Nördlingen. He had been seriously wounded at Nördlingen while helping avenge a rare earlier defeat of Turenne at Mergentheim.

Condé, unlike Turenne a Catholic, had remained loyal to the crown during the first Fronde revolt but had switched sides during the second and been thrown into the Bastille after losing the Battle of Faubourg Saint-Antoine to Turenne on the outskirts of Paris in 1652. Released by Queen Anne in recognition of his noble bloodlines and his previous service to the throne, the Great Condé, as he had become known, immediately left Paris and offered his services to the Spanish king, Philip IV, his former archenemy. Pleased to have such an experienced general on his side, Philip ignored their previous enmity and gave Condé command of his main army in the field.

FOR THE PAST FOUR YEARS TURENNE AND CONDE HAD SPARRED ALONG THE DISPUTED BORDER between northern France and the Spanish Netherlands, trading victories and defeats. Seeking to break the stalemate, Richelieu’s successor, Cardinal Jules Mazarin, proposed a new alliance with Spain’s other major enemy, the Commonwealth of England. The English Protestants—the Roundheads—under Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, had thrown off the shackles of their own hereditary monarchy a decade earlier and chopped off the head of King Charles I in the process. In the king’s place, the Roundheads had instituted a de facto Protestant theocracy—a development that Mazarin conveniently overlooked in his ongoing negotiations with England. Cromwell, for his part, seemed to regard the French as less stringently Catholic than the Spanish, whose industrious privateers had seized, in a single year, nearly 2,000 English ships from their coastal stronghold at Dunkirk. To Cromwell, the enemy of his enemy was his friend.

Charles I’s eldest son, Charles Stuart, had narrowly escaped death after his defeat by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. That defeat had necessitated six weeks of hair-raising flight, with Charles creeping across the English countryside at night from attic to outhouse to priest’s hole before he managed to escape to the continent. Dismissively called “the Pretender” by Cromwellians, he had spent the next several years in Paris, nursing grudges, spinning plots, and playing the angles in the ongoing power struggle between Spain and France. When he wasn’t plotting, he was womanizing. He promised lavish rewards for momentary pleasures, but with no intention on either hand of keeping his word.

In a bid to curry Cromwell’s favor, Mazarin abruptly expelled Charles and his entourage from Paris in 1654. “You will do well to put him in mind that I am not yet so low,” a humiliated Charles warned, “but that I may return both the courtesies and the injuries I have received.” Two years later Mazarin agreed to support a joint Anglo-French expedition against the Spanish forces in the Netherlands. France would provide 20,000 men, England 6,000 foot soldiers and an English fleet to blockade the ports of Dunkirk, Mardyke, and Gravelines. After capturing those cities, the allies would divvy up the spoils, with England taking title to the first two and France assuming control of the third. The agreement would be in effect for one year only, starting in 1657. For both sides, the clock was ticking.

Along with his religious differences with Spain, Cromwell harbored a deep personal grudge against the country, stemming from the dismal failure of his overly ambitious transatlantic campaign two years earlier. In the winter of 1654–1655, determined to strike a crushing military and economic blow to Spain by seizing its lucrative colonies in the West Indies, Cromwell had launched a joint army-navy operation to ferry thousands of English soldiers halfway around the world to the Spanish-held island of Hispaniola (now Haiti). Once there, the soldiers would drive off the Spaniards and make the island a forward base for expanding English interests in the New World.

But problems arose before the first English ship ever left port. Preoccupied with pressing affairs of state, Cromwell had delegated the planning of the expedition, known as the Western Design, to subordinates. Supplies for the five-week voyage across the Atlantic were inadequate, and the miserably seasick soldiers were penned below decks on the 40-ship task force and forbidden to go topside, lest they get in the sailors’ way. By the time they made landfall in Barbados a month later, many of the soldiers could barely walk, much less mount an effective attack. To make matters worse, supply ships carrying the men’s muskets and swords failed to arrive in time, and the English were ultimately forced to attack Santo Domingo, Hispaniola’s capital, armed only with homemade pikes. Raging thirst and venomous snakes plagued the soldiers every step of the way.

The Spanish defenders, with weeks to prepare, easily repelled the English attack. The battered invaders limped back to their ships and sailed to Jamaica. There they had better luck, bombarding the island from the sea and storming Spanish-held Port Royal by land. Leaving behind an occupying force of 7,000 soldiers and sailors, Sea General William Penn and Colonel Robert Venables, the joint commanders of the expedition, returned to England, where Cromwell promptly threw them both into the Tower of London for leaving their posts without his approval. Within six months, nearly 4,000 of the men they had left behind in Jamaica died of disease, deprivation, or wounds inflicted by Spanish guerrillas. Angry and embarrassed, Cromwell vowed revenge. His treaty with France was the first step in that direction.

In the meantime, unaware of Cromwell’s diplomacy, Charles Stuart secretly met with Philip IV and urged him to invade England and seat Charles on the empty throne. In return, Charles promised to restore Jamaica to Spain and abjure any further English encroachments into the New World. To cement the deal, he offered to provide 2,000 English troops under the command of his brother James, the Duke of York, to Philip’s army in the Netherlands. (James had served under Turenne in the Fronde wars and disapproved of Charles’s overtures to Spain, to no avail.) The numbers were insignificant; it was mainly a symbolic gesture on Charles’s part designed to underscore his intention to return to his homeland—with his shield or on it.

Not that Charles, still licking his wounds from his thrashing at Worcester, intended to personally lead anyone into battle. He had tried that once already and nearly lost his head. His role now was to get other men to risk their heads. In this endeavor he was surprisingly effective. Responding to his royal summons, hundreds of Englishmen serving in the various continental armies rallied to his cause. He managed to scrape together five regiments—one Scottish, one English, and three Irish—and induced his reluctant brother James to leave Turenne’s army and assume command of the Royalist contingent in Condé’s.

Cromwell was not overly alarmed by Charles’s not-so-secret diplomatic or military efforts. The Pretender, he scoffed, was “damnably debauched. Give him a shoulder of mutton and a whore, that’s all he cares for.” Another disgusted Protestant observed: “Of all the armies in Europe there is none wherein so much debauchery is to be seen as in these few forces which the said King hath gotten together. Fornication, drunkenness and adultery were esteemed no sin amongst them.” The Irish troops in particular were renowned for their begging and their thievery. Those were handy skills to have since Charles’s supporters at Bruges, ill clothed and ill fed, shivered hungrily through the damp Flemish winter. They called themselves “the naked soldiers,” meaning it literally, and they were not above robbing local residents or stealing gold plate from the Catholic church. They even ate dogs when they could get their hands on them. When Charles narrowly escaped death one night at the hands of a panicky sentry who unloosed a round of buckshot at the royal party, many wondered if it was really an accident.

Meanwhile, Cromwell completed his bargain with Mazarin. Announcing his treaty with the Catholic French, the Protestant Cromwell sought to justify war with Spain by depicting England as the righteous avenger of New World natives who had been systematically colonized and brutalized by the Spanish over the past two centuries. Puritan poet John Philips drove home the point in a fiery pamphlet titled “The Tears of the Indians: Being an Historical and True Account of the Cruel Massacres and Slaughters of Above Twenty Millions of Innocent People.” Philips’s pamphlet, dedicated to Cromwell, painstakingly detailed Spanish abuses from the first conquistadors onward. Cromwell himself appeared before Parliament and bluntly warned: “Why, truly, your great enemy is the Spaniard. He is a natural enemy, by reason of that enmity that is in him against whatever is of God. He hath an interest in your bowels.”

Cromwell was scarcely overstating the point. The two nations had been at each other’s throats since the English scuttled the Spanish Armada in 1588 and turned back Spain’s last serious attempt to unseat Queen Elizabeth I. Whatever the rationale for renewed war, the Anglo-French alliance proceeded slowly. In May 1657 Turenne assumed overall command of the combined forces. John Reynolds led the English contingent, six all-Protestant regiments, many of them veterans of the recent French civil war. Under the terms of the agreement, Scotsmen and Irishmen were excluded from serving in the army on the debatable grounds that they could not be trusted to bear arms against their fellow Catholics. Clothed in the bright red coats of Cromwell’s vaunted New Model Army, a uniform that in time would become familiar around the world, the Protestant soldiers followed the aggressive philosophy of Puritan theologian Samuel Rutherford: “The want of fighting were a mark of no grace. Without running, fighting, sweating, wrestling, heaven is not taken.” Since its founding in 1645, the New Model Army had done more than its fair share of fighting, sweating, and wrestling—from Hispaniola and Jamaica to Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and England.

The pragmatic Turenne did not share his allies’ thirst for what they considered righteous battle. He would bide his time. Rather than head immediately for the Flemish ports, as Cromwell wanted, Turenne moved inland instead, marching and countermarching through Luxembourg in a fruitless attempt to lure Condé into battle on less favorable ground. Cromwell, accustomed to a more direct and aggressive approach to war, grew increasingly impatient with the Frenchman’s intricate tactics. He threatened to pull out of the alliance altogether if Turenne did not move at once against the enemy’s coastal strongholds. With illness and desertion having already reduced English ranks by a third, Turenne reluctantly agreed to attack. On September 19, the army arrived on the outskirts of Mardyke, near Dunkirk, on the northern coast of France.

While Turenne advanced, however measuredly, across the Netherlands, Charles Stuart continued to pressure the Spanish to help him mount a cross-Channel invasion of England. But that plan was proving futile. The English navy, operating off the coast of Cadiz, had recently sunk one of the two “silver fleets” that annually carried back to Spain her ill-gotten booty from the Americas. With the loss of £600,000 of long-awaited riches, King Philip could barely support himself, much less take on the additional expense of an amphibious invasion of England in support of a foppish playboy and his insufferable retinue. Charles would have to fend for himself—something in recent years he had gotten all too used to doing.

Marooned in Bruges, Belgium, which the English sourly branded Bruges-la-Morte because it was so deathly boring there, Charles busied himself with ever more outlandish invasion plans, ranging from a diversionary landing in Scotland to the assassination of Cromwell by a former military ally, Edward Selby. Dubbed “the Agitator” for his combative personality, Selby effectively torpedoed the assassination scheme at the outset by writing a pamphlet openly advocating Cromwell’s death. Selby cheekily dedicated the pamphlet, titled “Killing No Murder,” to Cromwell, declaring that “it is from your death that we hope for our inheritances.” Cromwell was not amused. He had Selby arrested and thrown into the Tower of London, where he soon died.

Undeterred, Charles continued plotting, corresponding with “the Sealed Knot,” a shadowy cabal of English Royalists who assured the Pretender that they were ready at a moment’s notice to rise up and install him on the throne. Charles sweetened the pot with a standing offer to pay anyone who would kill Cromwell £500 a year for life. (The offer went unclaimed.) Charles also cultivated King Philip’s illegitimate son, Prince Juan José of Austria, the progeny of the king’s longstanding affair with Maria Calderón, a Spanish actress. The only one of the king’s many illegitimate offspring to be formally recognized and educated at court, the 29-year-old Juan José was now governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands. Charles assiduously charmed the younger man, and the two attended lavish concerts, balls, and parties together. But Juan José, like his father, suffered from a continual lack of funds, and though Charles raged in private about his “scurvy usage” at the hands of his Spanish hosts, he could do nothing to advance his dream of a cross-Channel invasion.

Charles’s prospects darkened even further when Turenne’s forces captured Mardyke on September 21 and handed over the harbor, considered the best deepwater port on the Flemish coast, to Cromwell’s supporters. A month later Charles joined Juan José in a desultory attempt to retake Mardyke. Cromwell’s men easily repelled the Spanish counterattack and came near to killing Charles when a Puritan cannonball bounded past his head and disemboweled a courtier’s horse next to him. Once again, Charles had dodged death by a matter of inches.

Prevailed on by his aides not to risk the royal personage again in open combat, a plea that Charles found easy to grant, he relocated to Antwerp for the winter. There he resumed his correspondence with plotters back in England and continued to grouse about the reluctance of the Spanish to mount an amphibious invasion across a channel that was, by then, swarming with English blockaders. The Spanish, he said with sweeping self-interest, “had grossly failed in all their undertaking to send the King into England.” Charles, for his part, failed to see that it was not Spain’s primary—or even secondary—goal to make him king, although of course it remained his sole objective.

Charles did succeed in enticing some of the Protestant defenders at Mardyke to desert to the royal standard. At the same time, Reynolds, the English commander there, conducted an ill-advised parley with Charles’s newly arrived brother, the Duke of York. The two generals merely exchanged civilities between their lines, but Reynolds’s less-civil fellow officers were so critical of his contact with a member of the despised royal family that he immediately rushed back to England to explain himself to Cromwell. On December 5 Reynolds’s ship foundered on the Goodwin Sands, and Reynolds drowned before he could make his explanations. He was replaced at Mardyke by Major General Thomas Morgan, who wisely held no further meetings with the opposing side.

Prodded continually by Cromwell to capture Dunkirk, Turenne broke camp at last in the spring of 1658. Mustering his forces at Amiens, he set out in May at the head of a 25,000-man army. Meanwhile, elbowing Condé aside and assuming personal command of the Spanish forces, the less experienced Juan José completely mistook Turenne’s intentions and rushed east instead to reinforce Cambrai, leaving the English contingent at nearby Cassel unprotected. Turenne’s men fell upon the unsupported regiment and annihilated the Royalists to a man. Charles’s youngest brother, Henry, Duke of Gloucester, commanded the regiment on paper, but he had had the good fortune to fall ill a few months before and go to the rear to recuperate, thus postponing his own date with destiny. (In September 1660 Henry would die of smallpox at age 21.)

Temporarily unimpeded, Turenne reached the outskirts of Dunkirk in early June and immediately threw up two siege lines to block any attempt to resupply the defenders by land. Offshore a force of 18 English ships likewise embargoed the town from the sea. Belatedly realizing his mistake, Juan José hurried to relieve Dunkirk. It was a daunting task, made more so by the fact that he had far fewer men than Turenne—about 16,000 in all, counting the English Royalists. Adding to Juan José’s problems, the relief party soon outdistanced its artillery, whose progress was slowed by the marshy terrain. They would soon pay dearly for the delay.

ON THE AFTERNOON OF JUNE 13, JUAN JOSE ARRIVED AT A CRESCENT-SHAPED RANGE of sand hills a few miles northeast of Dunkirk and began deploying his troops in two wings. Condé commanded the left; the Duke of York guarded the right. Taking the high ground, Juan José aligned his forces perpendicular to the shoreline. His right flank, held by his Spanish Netherlands troops under Brigadier General Don Gaspar Boniface, was anchored on a 150-foot-high sand dune. The other forces, right to left, included the English Royalists, the Germans, the Walloons, and the French, the last directed personally by Condé, who, having been demoted, insisted on that prerogative. Two lines of cavalry under Don Luis de Caracena massed behind the front, with the remainder dispersed along the Spanish left flank, which rested on a road and canal that ran parallel to the shoreline.

Juan José did not intend to offer battle until his entire army was in place, but the uncharacteristically quick-moving Turenne gave him no choice. Leaving behind 6,000 men to guard the siege works at Dunkirk, Turenne swung north to confront the Spaniards in the sand dunes above the city. French cavalry deployed on both flanks, and seven English infantry regiments under Sir William Lockhart of Lee and General Morgan massed on the left, supported by cannon fire from the English ships. Although sporadic and not particularly accurate, the fire from the ships nevertheless compelled Juan José to move his own cavalry to his left to avoid shelling. It was a fatal mistake.

Turenne halted for the night on a low ridge 500 yards from enemy lines. The next morning Cromwell’s infantry began trudging through the dunes toward Dunkirk. Ahead of them waited the main Spanish position. It was 10 a.m. The tide was flooding out as Lockhart’s soldiers moved into position, their red coats shimmering in the sun. Musketeers and pikemen massed while the French cavalry of Jacques, marquis de Castelnau, covered their wings. The horses’ hoofs rested in the receding water at the edge of the beach. Turenne had carefully timed his advance for low tide, when the infantry and cavalry could move unimpeded up the beach beyond the enemy’s flank. He intended to halt 600 yards from the Spanish position and see what the enemy would do next.

But Turenne had not counted on the courage of the English Protestants or their simmering hatred for all things royal. Just ahead, they knew, waited the Duke of York and the remnant supporters of the dead king and his presumptive heir. An angry murmur swelled to a roar as the English footmen broke for the front, shouting their familiar battle cry: “The Lord of Hosts!” French marksmen rushed to their aid, peppering the Spaniards with musket fire as Lockhart and his men charged up the sandy hillside.

Startled by the unexpected English advance, Turenne recovered quickly and sent the cavalry of François, marquis de Crequy, racing forward to support them, while the rest of the infantry, including regular French troops and Swiss mercenaries, surged toward the center. Meanwhile, on the allied left, Lockhart’s infantry stubbornly climbed a commanding sand dune and pitched headlong into the Spanish defenders, who were arrayed in their time-tested tercio formation—pikemen first, then swordsmen and musketeers. Bitter hand-to-hand combat commenced beneath the broiling Flanders sun. The men on both sides were battle-hardened veterans, the English of their country’s civil war, the Spanish of the Thirty Years’ War, and the French of the three wars of the Fronde. They all knew how to fight.

BACK AND FORTH THEY SURGED. IN THE END, RELIGIOUS ZEAL CARRIED THE DAY. While Condé held his own on the Spanish left, Lockhart’s Roundheads overwhelmed the dune’s defenders and dashed down the far side after them. Lockhart’s regiment bore the brunt of the fighting, losing its second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Roger Fenwick, two captains, and 40 to 50 foot soldiers in the charge. Almost all the regiment’s officers were wounded in the attack. Roger Lillingston’s regiment, in close support, lost a captain and another 30 to 40 men. “They came on like wild beasts,” one Spanish survivor said of the English attackers.

The Duke of York bravely rallied his cavalry, personally leading several countercharges, but Castelnau’s horsemen, controlling the flank, got around him and sent the whole right wing of the Spanish army into retreat. The Germans and Walloons in the center gave way, followed finally by Condé’s French. Juan José galloped away to Dunkirk. At the same time the tide began rushing back in, making it impossible (as Turenne had foreseen) for the Spanish cavalry to counterattack. The Royalists fell back in orderly but hasty retreat. The Irish regiment, commanded by Colonel Richard Grace, made a brief stand in the center but soon gave way. Condé, after being unhorsed and nearly captured, withdrew as well. He and Juan José reunited south of Dunkirk. Behind them, Turenne and his English allies were masters of the battlefield. The entire event had lasted a mere two hours.

At the comparatively low cost of 400 men, mostly English, Turenne’s army had killed or captured 15 times that number. Napoleon Bonaparte, a brilliant tactician in his own right, would later declare the battle Turenne’s “most brilliant action.” Knowing their likely fates, the defeated English Royalists rushed to surrender to French troops; one unfortunate sergeant fell into Roundhead hands and was hanged on the spot as a traitor. The Duke of York managed to get away—the younger Stuarts proved far better at escape than their father—and retreated to Nieuwpoort, 23 miles north of Dunkirk. Ten days later the garrison at Dunkirk surrendered to Turenne, leaving him in complete control of Flanders and the Flemish coast. On June 15 King Louis XIV personally handed over the city to Lockhart in recognition of his leading role in the battle. Turenne continued campaigning and in short order captured the Flemish towns of Furnes, Dixmude, Gravelines, Ypres, and Oudenarde.

Waiting apprehensively in Brussels, Charles got word of the Spanish defeat and fled immediately for the Dutch border, taking refuge at Hoogstraten. Remarkably, he then resumed his wastrel life as though nothing had happened. Two months later, while out hunting partridges with his fleet of royal hawks, he received the unexpected news that “the great monster” Cromwell was dead. The Lord Protector had succumbed on September 3 to a sudden bout of malaria, complicated by grief over the death of his favorite daughter, Elizabeth, a few weeks earlier. It would take another 18 months of subtle diplomatic maneuvering before Charles set foot once again on English soil—no thanks to the Spanish, who concluded a separate treaty with France in November 1659 and gave up their last strongholds in the Netherlands. The English navy controlled the coast.

After Cromwell’s death the Protestant Commonwealth quickly fell into disarray, and army commander George Monck, Duke of Albemarle, seized control of Parliament and negotiated with Charles to disband the New Model Army and restore the Stuarts to the throne. Charles, in gratitude, raised Monck to baronet, gave him an annual pension of £7,000, and awarded him with a large swath of land in present-day North and South Carolina. All court documents were backdated to read as though Charles had succeeded his father as king in 1649.

On assuming the throne in 1660, one of Charles II’s first official acts was to have Cromwell’s body disinterred from its place of honor at Westminster Abbey and hanged in chains like a common thief at Tyburn on the 12th anniversary of Charles I’s execution. In an entirely redundant exercise in delayed revenge, the corpse was then beheaded, and Cromwell’s skull was stuck on a pole outside the abbey, where it remained in place for the next 28 years. For centuries to come, English schoolchildren would recite the macabre nursery rhyme: “Oliver Cromwell lay buried and dead, / Heigho! Buried and dead! / There grew a green apple-tree over his head. / Heigho! Over his head!” By then both Cromwell and Charles were beyond caring. In a final bit of irony, Charles sold Dunkirk back to France two years later for £320,000. MHQ

Roy Morris Jr. is the author of eight books, including, most recently, American Vandal: Mark Twain Abroad (Harvard University Press, 2015).

[hr]

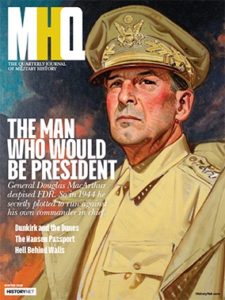

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Dunkirk and the Dunes

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!