The Gatling gun, precursor to the fearsome modern machine guns that have wrought gruesome havoc on global battlefields since World War I, was invented by Richard Gatling in 1861. The introduction of a rapid-firing marvel like the Gatling early in the war should have given Union officials plenty of time to acquire and deploy it in combat. But, despite the lethal potential of what Gatling called his “Revolving Battery-Gun,” it is possible only a handful were ever used during the conflict. To his credit, Gatling energetically promoted his revolutionary weapon, even appealing directly to President Abraham Lincoln, but he was largely ignored. Union armies would continue to fight without this groundbreaking device—what may well have become the Civil War’s deadliest weapon.

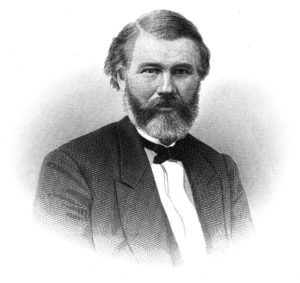

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]ichard Jordan Gatling was born September 12, 1818, in Hertford County in northeastern North Carolina, near the Virginia line. Although he received a medical degree in 1850, Gatling never practiced medicine. Instead, he worked at a variety of jobs, including schoolteacher, county clerk’s assistant, dry goods store merchant and self-employed businessman. Yet Gatling’s consuming, lifelong passion was inventing, and he proved to be prodigious. From his first known invention at age 21 (a steamboat screw propeller) until his death on February 26, 1903, at age 84, Gatling churned out dozens of ingenious inventions for improving daily life in the home and on the farm. These ranged from more efficient toilets to rapid planting devices (notably a rice-sowing machine and a wheat drill) to steam-powered farm implements.

In 1854, at age 36, he moved to St. Louis, and by 1861 was living in Indianapolis. The war’s outbreak turned the inventor’s attention from farm fields to battlefields. In a postwar letter, Gatling revealed:

It occurred to me if I could invent a machine—a gun—which could by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a great extent, supersede the necessity of large armies.

By the end of 1861, he had designed his “Revolving Battery-Gun” prototype.

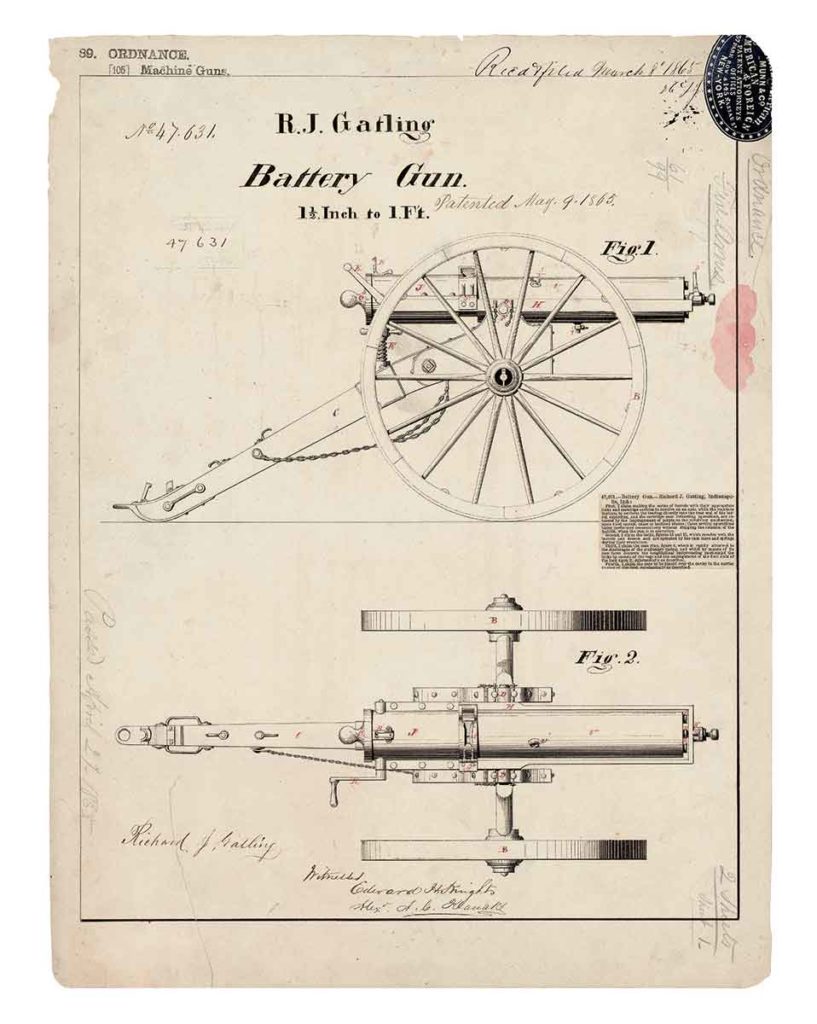

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen Gatling received U.S. government Patent No. 36,836 for his gun on November 4, 1862, it was not the Civil War’s first rapid-firing weapon. The most notable of the Gatling’s competitors was inventor Wilson Agar’s Union Repeating Gun—nicknamed the “Coffee Mill Gun” because its top-mounted hopper-loader and hand-crank firing mechanism resembled that kitchen utensil. After Agar (sometimes spelled “Ager”) demonstrated his single-barreled, two-wheeled carriage-mounted weapon to Lincoln in 1861, the president advised its purchase—several dozen Coffee Mill Guns (capable of firing 120 rounds per minute) were obtained, a few of those eventually used in combat. Rapid firing, however, tended to overheat the gun’s single barrel, and its hopper and breech often jammed.

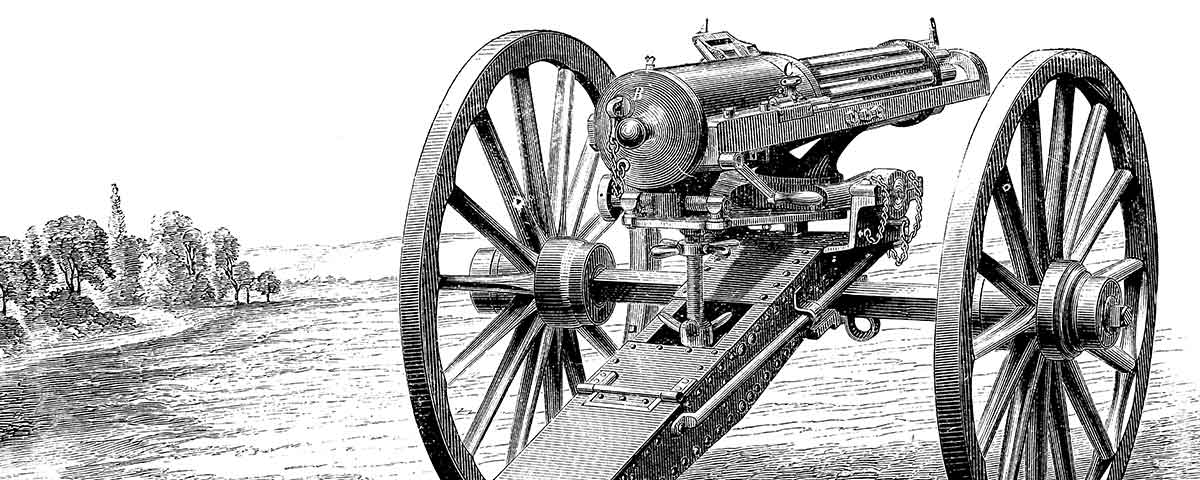

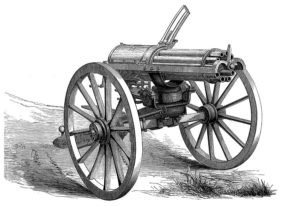

In fact, the Civil War Gatling had several common features with Agar’s gun: Both had similarly style top-mounted hopper-loaders (what Gatling called “reservoirs”) for feeding loose rounds of ammunition into the weapon; each was mounted on a two-wheel gun carriage; and firing was by a hand-crank. But Gatling’s innovation was to use six ordinary rifle-musket barrels, each with its own breech, revolving around a central horizontal axis. A brief interval between firing rounds through each barrel prevented overheating, allowing a remarkable rate of fire of 150 rounds per minute.

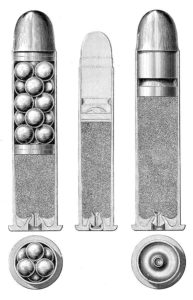

Like the hopper-loader, carriage, and hand-crank it shared with Agar’s gun, the Civil War Gatling fired the same ammunition—standard .58-caliber rifle-musket paper-wrapped cartridges containing bullet and black powder charge. Each cartridge was placed inside its own specially constructed “cartridge chamber”—a steel tube, open on one end (to load the cartridge), and closed on the other end with a rifle-musket nipple for a standard percussion cap. After firing, each empty cartridge chamber fell to the ground by gravity when the fired barrel rotated to the bottommost position. Empty cartridge chambers were collected and subsequently reloaded with new paper cartridges and percussion caps—a laborious, time-consuming process.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Gatling’s innovation allowed for a 150-round-per-minute rate of fire that could be sustained indefinitely[/quote]

Although patented in November 1862, the Gatling already had been successfully demonstrated, notably on July 14, 1862. On that day, T.A. Morris, A. Ballweg, and D.G. Rose tested the gun at Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton’s direction. Their enthusiastic report: “The discharge can be made with all desirable accuracy as rapidly as 150 times a minute, and may be continued for hours without danger, as we think, from over-heating.” Unfortunately for Gatling, Morton declined to buy the weapon, a pattern of refusals to be repeated throughout the war.

Gatling’s innovative firearm faced a firmly entrenched roadblock: Brig. Gen. James Wolfe Ripley, Union Army chief of ordnance. Ripley (born in 1794) considered repeating weapons unnecessarily expensive inventions that encouraged ammunition waste, thereby overburdening the Army supply system. Ripley stubbornly resisted all rapid-fire weapons (in addition to Gatling and Agar guns, blocking or delaying Sharps, Spencer, and Henry rifles), claiming single-shot, muzzle-loading, rifle-muskets “good enough.” Gatling called Ripley “an old fogey” who “believed flintlock muskets were on the whole the best weapons for warfare.” In an 1863 meeting, Gatling recalled, Ripley “received [Gatling’s agent] coldly,” told him “he had no faith in the [Gatling] gun” and that “he would have nothing to do with him.” Gatling persevered, going straight to the top.

Since Lincoln had championed repeating weapons—notably, the Spencer repeater and Agar’s Coffee Mill Gun—Gatling appealed directly to the president. In a February 18, 1864, letter to Lincoln, Gatling pleaded his case (with a swipe at his competition):

[My gun] is regarded by all who have seen it operate, as the most effective implement of warfare invented during the war….[I]t is just the thing needed to aid in crushing the present rebellion [emphasis in original]….I assure you my invention is no “coffee mill gun”—but is entirely a different arm, and is entirely free from the accidents and objections raised against that arm.

Lincoln ignored him—most likely for politics than for doubts about the gun’s capabilities. Gatling’s Southern roots raised doubts about his loyalty, and his name was linked with Northern Copperhead politician Clement L. Vallandigham—a “whispering campaign” probably promulgated by competitors alleging Gatling held membership in a Southern-sympathizing secret society, the Order of American Knights. Always pragmatic and facing reelection, Lincoln feared Gatling being in league with Copperheads.

A direct appeal by Gatling produced no U.S. government contract during the war. Still, it remains widely claimed that at least some Gatlings saw combat use. Publications mentioning Gatling guns typically insist they “were first used in combat in the Civil War.” The mostly anecdotal evidence offered to substantiate this, however, is suspiciously thin and undated—hardly conclusive proof.

It is asserted that Union Army of the James commander Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler personally bought 12 Gatlings (for $1,000 each, though Gatling’s agent embezzled the money) and that he briefly used a few to fire on enemy forces “near Richmond” during the siege of Petersburg. Butler allegedly mounted up to eight on Union James River gunboats. Even then, no claim has been made that those gunboat Gatlings were fired in anger during combat.

After the war, Gatling would boast: “Ben Butler took the guns he had with him to the Battle of Petersburg and fired them himself upon the rebels. They created great consternation and slaughter.” Obviously, Gatling was not a disinterested party. He, of course, had a financial stake in promoting his weapon as vigorously as possible. Tellingly, Civil War firearms historian William B. Edwards points out that Butler, a notoriously self-promoting individual who seldom missed a chance to brag of his accomplishments, “neglects to mention this colorful use of an important novel weapon of war.” The failure by Butler to mention Gatlings “is conspicuous” by its absence, Edwards concludes.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]No verifiable proof exists that gatlings were ever used in combat during the war[/quote]

Edwards also explains revealingly that in February 1864 Butler officially obtained 10 Agar Coffee Mill Guns from the Washington Arsenal (Ripley, by then, no longer around to block their issue) and concludes that the confirmed possession of those Agar guns “must be assumed [the] ‘Gatlings’” that Butler placed on the James River gunboats.

Further muddying the water regarding the possibility of Gatling gun Civil War combat use is the fact that few soldiers in the Union Army had ever laid eyes on either Agar or Gatling guns. This unfamiliarity with the weapons led to, as Edwards points out, the “contemporary [i.e., Civil War] confusion…that made soldiers and commanders interchange [Agar’s] Union Repeater and the Gatling Battery Gun” when referring to the rapid-fire weapons. Even if soldiers at the one alleged Petersburg/Richmond combat use had seen a rapid-fire weapon being fired against Confederate troops, they likely would not have known if it was a Gatling or one of the Agar guns Butler certainly had.

Although Admiral David Dixon Porter purchased a small number of Gatlings (likely only one) to mount on Navy river gunboats in the West, there is no record of any combat use. Another claim, that Gatlings were used to suppress the July 13-16, 1863, New York City Draft Riots, seems based on Gatling having sent three of the guns to newspaper publisher Horace Greeley (presumably to display as a publicity stunt) and that during the riots the guns were “ensconced in the windows of [Greeley’s] New York Tribune,” their mere presence having “turned away a serious threat of attack by the mobs” on one occasion, Gatling would later claim.

The bottom line is that no verifiable proof exists that Gatlings made it into combat during the war beyond the unsupported claims of Gatling himself and some postwar books written by his friends and publicists. Indeed, even Gatling’s grandson admitted in 1957: “No one seems to know any anecdotes on the Civil War use of the gun.”

Yet the tantalizing “what if?” vision of Union armies armed with dozens of Gatlings sweeping the battlefields clean of Confederate troops and, thereby, shortening the war, fades upon closely and critically examining the weapon’s mechanical and tactical limitations. The Civil War–era Gatling differed significantly in several key aspects from Richard Gatling’s much-improved postwar models, whose substantially greater reliability and efficiency provided armies around the world with a significant source of firepower for nearly half a century.

Gatling’s ‘Revolving Battery-Gun’

Patented November 4, 1862 | Era 1862-1865

Caliber

.58 (standard rifle-musket paper cartridge with percussion cap)

Ammunition Feed System

Gravity fed via hopper-loader

Firing System

6 rotating barrels

Firing Mechanism

Hand-crank

Rate of Fire

150 rounds per minute

Barrel Length

32 inches

Overall Length

60 inches

Weight of Gun (minus carriage)

About 400 pounds

Weight of Carriage

350–550 pounds

Transportation

Horse-drawn, moved short distances by gun crew

Crew

4-6 (Gunner, Loader, Ammunition handlers)

Mechanically, the top-mounted, gravity-fed hopper-loader into which loose rounds of ammunition were placed was, like those on Agar guns, inefficient and subject to jamming if the ammunition failed to drop smoothly into the barrels’ breeches. Moreover, the steel cartridge chambers loaded with .58-caliber paper cartridges primed with percussion caps were clumsy, time-consuming to collect and reload, and added burnt paper residue to the ever-present barrel-fouling black powder residue. The weapon also lacked a swivel mechanism on its carriage mount that would allow it to be fired quickly right or left—in other words, a horizontal sweep of the battlefield. Only gun crews physically manhandling the weapon’s carriage right and left could accomplish that. Even moving the weapon’s fire vertically was possible only via the primitive “elevating screw” it shared with standard field cannons.

Tactically, the Gatling had a potentially fatal deficiency in that when the enemy was within range, the gun, as well as its crew and horses, could be struck by enemy infantry fire—the same problem all field artillery crews faced. Although the Gatling’s firing rate could have unleashed a blizzard of bullets at any force attacking directly along a narrow route, that made it suitable only for firing from protected defensive positions.

The Gatling did not—indeed, could not have—become warfare’s “wonder weapon” until post–Civil War models that fired self-contained, metallic cartridges appeared. It was a killing machine of great future potential—it just wasn’t quite ready for prime time.

Jerry Morelock is America’s Civil War senior editor.