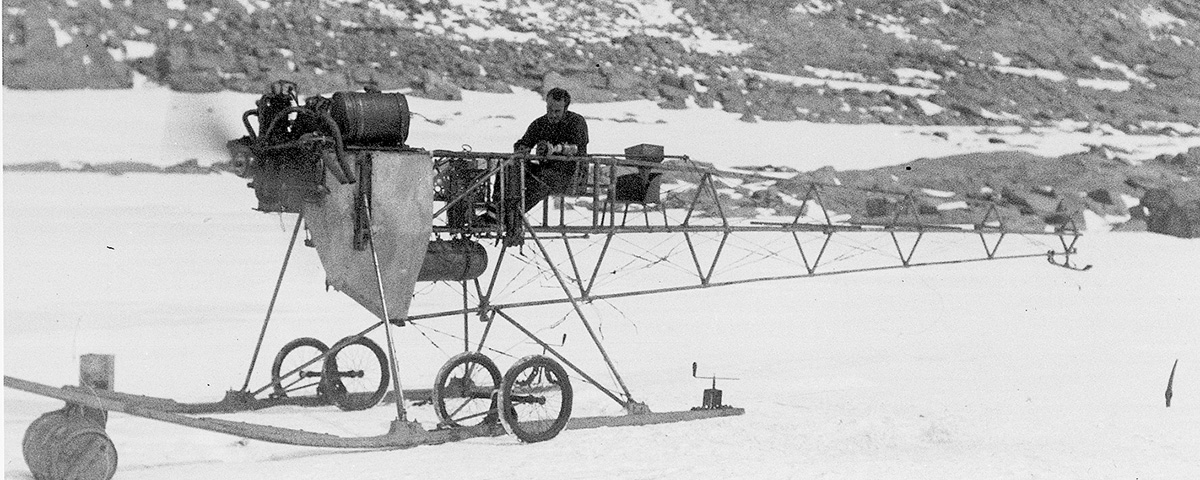

Douglas Mawson and his ‘Wingless Wonder’ headed for the Antarctic in 1911.

The three men were yoked like pack animals to a sled carting their supplies. They suffered from unrelenting frostbite, trudging along through the ice and snow, carrying with them only enough food to barely sustain life. Along the perilous route, hidden crevasses threatened to swallow them, and their objective was elusive. Exhausted by hunger and cold, the youngest man confided in his diary: “The Prof had talked of returning down coast in Jan, when much ice out, at average rate of 20m[iles] per day. I guess I would like to see [us] fly.”

It was 1908, and the writer was Douglas Mawson, a 26-year-old Australian professor at the University of Adelaide, in Antarctica as part of the 1907-09 British Antarctic Expedition (BAE) led by Sir Ernest Shackleton. Together with Edgeworth David (“the Prof”) and A. Forbes Mackay, Mawson journeyed 1,260 miles in 122 days to ascertain the position and directional movement of the south magnetic pole.

Mawson’s wry comment about flying was not just fatigue-induced sarcasm. An engineer and geologist, Mawson was fascinated with emerging technology and scientific advances. Always an innovator, throughout his life (1882-1958) he displayed a breadth of technical skills, including engineering, industrial and architectural design. He patented advances in ore processing, and pioneered techniques in forestry and erosion control. After gaining international acclaim for his role in the BAE, he became one of the foremost scientific figures in Australia, well known for leading two subsequent expeditions to Antarctica, championing environmental conservation and powering national-level Australian scientific research, education and policy. He was knighted in 1914, and today his likeness can still be seen on Australian currency.

In 1911 Mawson began planning his own expedition, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE), to map the Antarctic coastline directly south of Australia. The AAE would depart from Australia in December 1911 in the expedition ship Aurora. Under the command of Captain John King “Gloomy” Davis, the ship would return to retrieve the expedition in early 1913. The AAE was primarily supported by the Australian scientific community, a group long on enthusiasm but short on funds. This did not stop Mawson from ambitiously planning to be the first to take an airplane to the Antarctic.

But the fates were against him—his plane would never fly in Antarctica. In fact, 18 years would go by before anyone actually fulfilled that dream. Mawson’s plane did not even arrive in Antarctica intact. It did, however, help to save his life.

Mawson’s plans called for an aircraft that was durable and reliable enough to withstand the harsh Antarctic conditions. In May 1911, he had made an unsuccessful bid on a Breguet biplane. His unidentified agent sent him this message: “Here is the Breguet—this is a very fine machine, I think about as good as any biplane—but I know no one in connection with it and therefore could get no reduction in price….I greatly recommend a monoplane but not a Blériot, their only advantage is that they are fast and you don’t require that. There’s a lot of jobbery in the aeroplane market, that it is scarcely safe to take anyone’s advice. One should really rather fly [it].”

Later, assisted by noted British aviator Claude Graham-White, Mawson purchased a Vickers I monoplane, one of only eight such aircraft built by the shipbuilding and arms manufacturer. The Vickers featured a metal-fortified fuselage, making it more substantial than contemporary planes. The Adelaide Register newspaper described it as being “like a large bird of nickel steel. It had a body 34 feet long from nose to tail, was capable of remaining in the air for 5 hours and could cover 300 miles in that time.” The power plant, built by French aviation pioneer Robert Esnault-Pelterie, was likely one of his 60-hp, 14-cylinder, four-row engines. The bill of sale, dated August 17, 1911, was itemized for the monoplane, a “special ice undercarriage” and shipping from England to Australia. Mawson hired Frank “Bick” Bickerton as mechanic and a Lieutenant Watkins as pilot, and sent them on to Adelaide with the plane.

Before sailing to Antarctica, Mawson planned to boost the AAE’s sickly finances with public flying demonstrations in Australia, where civil aviation was still a novelty. With Bickerton, Watkins assembled the Vickers and scheduled the first demonstration for October 5, 1911.

A test flight was planned before the main event. Watkins took off with expedition member Frank Wild, but the test ended in disaster when the plane crashed and rolled, damaging both wings and slightly injuring the two men.

Mawson’s dreams of flying above the merciless Antarctic surface were shattered. There was neither time nor money for complete repairs. Instead he detached the damaged wings, stripped the sheathing from most of the fuselage to conserve weight, fitted the undercarriage with outsize skis and rebaptized the plane an “air tractor sledge,” a reference to the cargo sleds used by polar explorers. He said that “the advantages expected from this type of machine were speed, steering control, and comparative safety from crevasses owing to the great length of the runners.”

By late January 1912, the AAE had established itself in Antarctica, with its main base at Cape Denison, south of Tasmania. The wingless Vickers was installed in a 10-foot-by-35-foot hangar abutting the living hut. Bickerton spent the polar winter there, reattaching the undercarriage and engine, which had been removed for the voyage, and configuring the machine so it could haul supplies over land during the summer exploration season (October 1912 to February 1913). Mawson would later write of Bickerton’s efforts: “[The air tractor sledge] spent almost the whole year [1912] helpless and driftbound in the hangar. During those months, Bickerton had expended a great amount of energy upon it, introducing brilliant ideas of his own…to adapt it to local requirements.”

On November 15, 1912, the first trial of the air tractor sledge was made, with Bickerton sitting high in the pilot’s seat. The fuselage was perched about 5 feet above the ground so that the propeller was well above any projecting ice. The undercarriage consisted of struts connected to long, snowboardlike skis to help it pass safely over crevasses. A team of men had to move it into position. Expedition member Charles Laseron recorded, “on a trial trip [it] roared its way up the first steep slope in great style.”

Bickerton later fashioned brakes and a steering mechanism from the original landing gear and hand drills used by the geologists. The machine subsequently carried cargo five miles up the ice slope behind Cape Denison to a depot used as a gateway to the Antarctic interior. Laseron wrote: “Bick’s aeroplane sledge was…doing yeoman service at this period….Its advent lightened the labor of all, for on every available occasion it took a load to Aladdin’s Cave [the depot], not only of petrol for its own use, but of stores for all the other sledging parties.” Mawson wrote happily of its performance: “In the execution of this work a speed of twenty miles per hour was attained up ice slopes of one in fifteen in the face of a wind of fifteen miles per hour. Bickerton has reason to feel highly elated with its success.”

The air tractor sledge’s next responsibility was to haul supplies for a team led by Bickerton to explore the coastal highlands immediately west of Cape Denison. The team left Cape Denison on December 3, with the Vickers towing a caravan of four sledges. What happened next is recounted in Mawson’s memoir, Home of the Blizzard. About 10 miles out, he recorded:

…the engine developed an internal disorder which Bickerton was at a loss to diagnose or remedy. This necessitated pitching camp for the night…at 4 p.m. next day, after drifting snow had subsided, the engine was started once more. Its behavior, however, indicated that something was the matter with one or more of the cylinders. Bickerton was on the point of deciding to take the engine to pieces, when his thoughts were brought to a sudden close by the engine, without warning, pulling up with such a jerk that the propeller was smashed. A moment’s examination showed that even more irremediable damage had occurred inside the engine, so there was nothing left but to abandon the air-tractor and continue the journey man-hauling their sledge.

Months later, Bickerson hauled the air tractor sledge back to Cape Denison and found that the pistons had seized and were irreparable. The culprit was the engine oil—in those low temperatures it congealed, becoming too thick for the pistons’ tolerance. Bickerton had tried to preempt this disaster by painting the engine and the oil tank black to absorb the sun’s heat, to no avail. The abandoned vehicle became a sort of landmark. The sledgers passed it as they came back to Cape Denison, bringing stories of their discoveries and their battles with the elements.

In early 1913, Captain Davis and Aurora returned to bring the AAE back to civilization. But Mawson’s three-man party, which had traveled by dog team to map the area far west of Cape Denison, was still in the field. Davis waited for Mawson as long as possible, until Aurora was in danger of being iced in, then sailed back to Australia in March. Aurora would return the next year. Five men, including Bickerton, remained at Cape Denison to try and discover what had become of their expedition leader and his companions, F.X. Mertz and B.E.S. Ninnis.

Mawson was the only one of the three who eventually returned to Cape Denison. After six weeks on the trail, on December 14, 1912, Ninnis and his dog sled disappeared into a crevasse, never to be seen again. Mawson and Mertz were left with one dog team, food for a week and a makeshift tent. They immediately turned back toward Cape Denison.

Mawson and Mertz resorted to eating their sled dogs as they died, finding the liver to be the most palatable. However, as proved 60 years later, Husky liver contains toxic amounts of vitamin A. Both men became dangerously ill with diarrhea, hair loss, peeling skin, disorientation and crippling head and body pain. Mertz succumbed to the poisoning on January 7, 1913.

Staggering, sometimes crawling, Mawson continued alone. His technical skills proved to be his salvation, as he modified his gear to compensate for his weakening state. He miraculously found a food cache on January 29, allowing him to make it to Aladdin’s Cave. There he was trapped by a week-long blizzard, surviving on supplies previously hauled by the air tractor sledge. On February 8 he made his way down the ice slopes to Cape Denison, using ice-shoes fashioned from the remnants of a wooden box. Bickerton was the first to reach the forlorn figure. He knocked the ice from around the man’s hood and saw Mawson’s emaciated face, patchy skin and sunken eyes. “My God,” Bickerton blurted, “which one are you?”

Undaunted, Mawson returned to Antarctica in 1929 in the expedition ship Discovery. During that trip, he was finally able to view Antarctica from the air when he flew as a passenger in a de Havilland Moth floatplane. He wrote about his first flight on January 5, 1930: “As we rose, a wider and wider view of the land unfolded. A black rugged Mountain appeared to the east of the rising plateau slopes.” Mawson had finally risen above the white hostility of Antarctica.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2004 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!