It is frequently presumed that Pickett’s Charge, on July 3, 1863, was doomed to defeat before a single cannon opened fire or a Confederate soldier stepped off toward Cemetery Ridge. No question, Lee’s plan for a massive frontal assault against the Union center on Gettysburg’s third day was a huge gamble that might cost him dearly in casualties. Two days earlier, however, he had watched his soldiers successfully execute a frontal assault on Seminary Ridge. The scale was smaller, but the risks were similar.

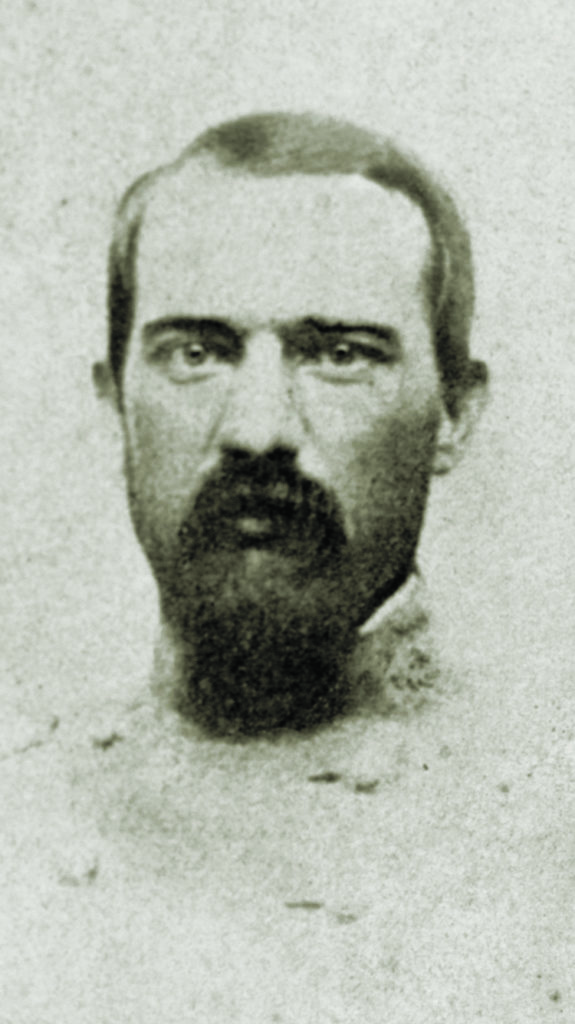

The attack on Seminary Ridge by Maj. Gen. Dorsey Pender’s troops, of A.P. Hill’s Corps, is not well known in the popular memory of the battle, and it doesn’t help that a portion of that hotly contested ground, owned by the Lutheran Theological Seminary, now holds a parking lot and that some terrain has been recontoured.

In 1862, Pender’s unit had been A.P. Hill’s famous Light Division, but when the Army of Northern Virginia was reorganized after Chancellorsville in May 1863, two brigades were transferred to create a new division under Maj. Gen. Henry Heth. The four remaining brigades featured crack combat veterans led by Pender, one of the rising stars in Lee’s army. On July 1, Pender’s men followed Heth’s Division on its reconnaissance-in-force up the Chambersburg Pike toward Gettysburg. After Heth suffered defeat during the morning action, Pender advanced to Herr Ridge, about two miles west of town. When the fighting renewed about 3 p.m., he advanced with three brigades to support Heth, fiercely engaged in bloody fighting along McPherson’s Ridge and Herbst Woods.

As the South Carolinians of Colonel Abner Perrin’s Brigade approached Willoughby Run, west of McPherson’s Ridge, they encountered a field “thick with wounded hurrying to the rear, and the ground was grey with dead and disabled” from Brig. Gen. James Pettigrew’s North Carolina brigade. Shocked by the combat they had just experienced, some of Pettigrew’s men warned the South Carolinians that “we would all be killed if we went forward.”

By 3:30 p.m., Heth, with help from Robert Rodes’ Division, had driven the Union 1st Corps from McPherson’s Ridge and Herbst Woods—at a frightful cost. Heth’s men were fought out and low on ammunition.

“We could see the Yankees running in wild disorder,” wrote a 1st South Carolina officer. To complete the rout, A.P. Hill was confident all he needed to do was commit Pender’s Division.

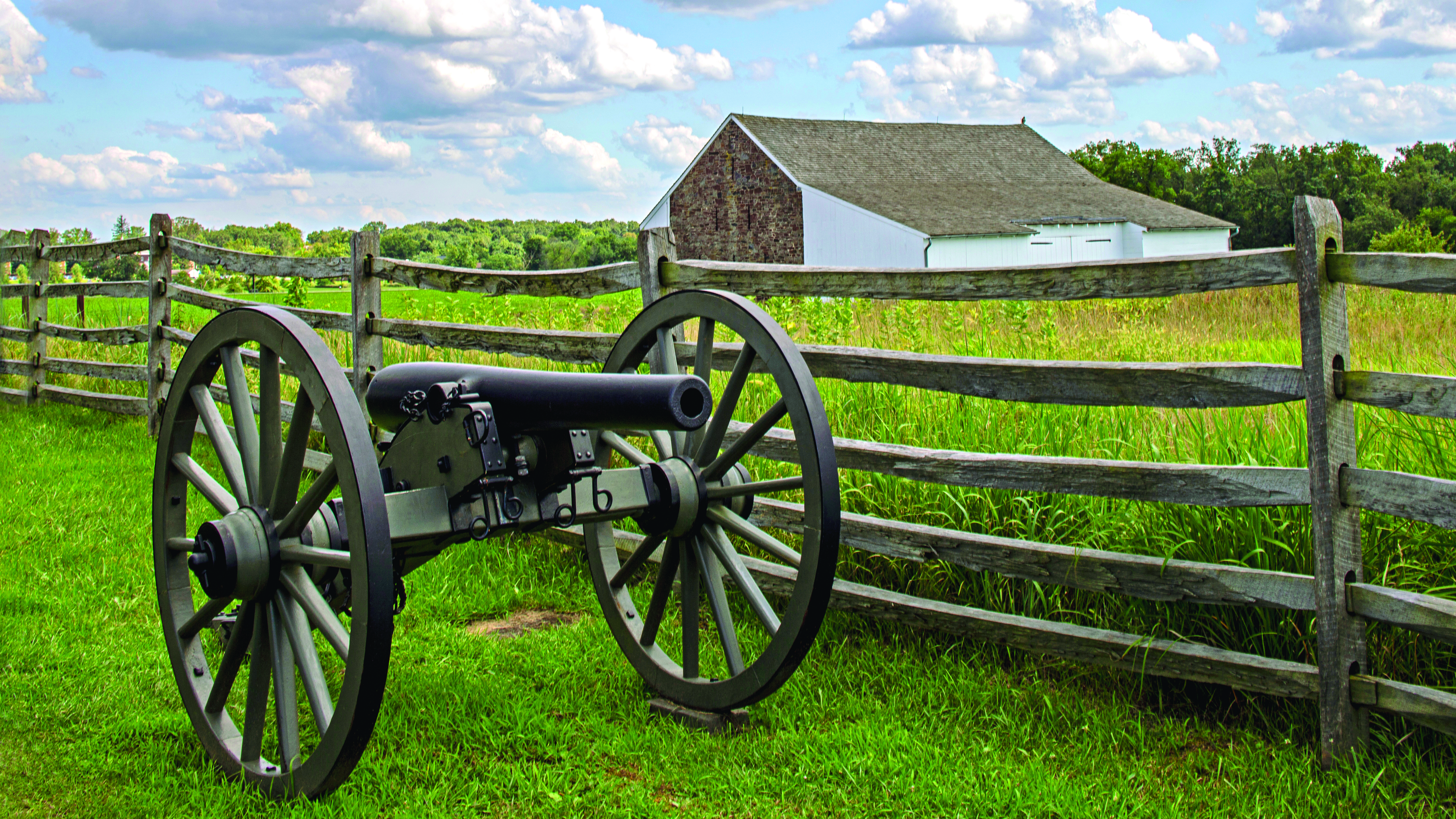

The Yankees were running, but they were far from routed. Rather, they were hurrying to cross the open space between McPherson’s Ridge and Seminary Ridge to get cover. Four 1st Corps batteries, with 22 guns, had been unlimbered along Seminary Ridge, from the unfinished railroad cut north of the Chambersburg Pike to the Hagers-

town Road. In the small wood lot directly in front of the Seminary building, 1st Corps soldiers earlier had dismantled fences and built a rail barricade that curved through the entire woods. Survivors of the Herbst Woods and McPherson’s Ridge fighting took cover behind the barricade or fell in between the artillery batteries and prepared to defend their position.

Pender wanted to have his men move swiftly in force and give the Federals no time to reorganize or rally. Before the Rebels could step off, however, Union Brig Gen. John Buford adeptly maneuvered his cavalry and impeded the movement of Brig. Gen. James Lane’s Brigade on Pender’s right, letting Pender advance with only two brigades: Brig. Gen. Alfred Scales’ North Carolinians and Perrin’s South Carolinians, about 3,000 men total.

At about 4 p.m., the two brigades started forward at a quick step. When they crested McPherson’s Ridge, the Union batteries, their guns loaded with shrapnel or canister, were ready. As the gray lines passed over the ridge, the guns opened fire with terrible effect. Scales’ Brigade took the brunt of that fire—“[e]very discharge made sad loss in the line,” wrote one North Carolinian—and Union infantry added to the slaughter, felling Scales’ men by the dozens. Though survivors managed to reach low ground between the two ridges, Scales reported, “our line had been broken up, and now only a squad here and there marked the place where regiments had rested.” Scales was wounded, all but one of his field officers had been shot, and the 13th North Carolina alone had lost 150 of 180 men. Some survivors lay down and began firing at the enemy. Others, panicked by the slaughter, fled back across McPherson’s Ridge.

On Scales’ right, a 14th South Carolina captain, whose regiment was advancing toward the barricade, described the ground before him as “the fairest field of fire and finest front for destruction on an advancing foe that could well be conceived.” Perrin was spared the worst of the artillery fire that had ripped Scales’ line, but the small-arms fire was murderous. The 14th South Carolina suffered 200 casualties.

Some of Buford’s dismounted troopers, south of the Hagerstown Pike, raked Perrin’s right with carbine fire, but Perrin, displaying remarkable coolness, dispatched two of his regiments to deal with Buford and, finding a seam in the Union defenses on Seminary Ridge, pushed Major C.W. McCreary’s 1st South Carolina (Provisional Army) through it, unraveling the entire Federal line.Charles Wainwright, the 1st Corps artillery commander, remarked as he watched the South Carolinians sweep forward in spite of heavy losses: “Never have I seen such a charge. Not a man seemed to falter. Lee may well be proud of his infantry.”

Though Pender’s Division endured approximately 1,100 casualties, his men pressed on into Gettysburg, scooping up hundreds of prisoners. But it proved a tactical, rather than operational or strategic, success. At the end of the day, the enemy retained the key terrain in the Gettysburg area. The subsequent fighting would cause Lee to attempt to duplicate the feat of Pender on July 3, this time with 11 brigades instead of two and with a massive artillery preparation.

As would be proved late in the day July 3, Lee miscalculated. The enemy were not the battered regiments and brigades that Pender had faced on Seminary Ridge, but determined infantry supported by a fearsome assemblage of artillery. Élan and courage carried the day on July 1. They would not on July 3.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.

This column appeared in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.