‘The Americans have . . . captured several of our frigates; but to-day, I trust, they will find out the stuff British sailors are made of’.

After the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy dominated the high seas and blockaded enemy ports, particularly those of Western Europe, trying to paralyze the navies of France and her allies and to control the flow of imports and exports. Napoleon’s response in late 1806 was to attempt to destroy Britain’s economy by closing ports to British merchant ships and to neutral vessels trading with Britain. The British government retaliated in early January 1807 by placing restrictions on neutral merchant vessels, forbidding them to move between enemy ports, and in turn Napoleon declared it illegal to comply with those regulations.

American merchant vessels were especially affected, as they were unable to collect cargoes for their return journey across the Atlantic. Commerce became a major source of aggravation between the United States and Britain.

Sailors were another area of contention between the two countries. Throughout the Napoleonic wars, the Royal Navy was always short of seamen and continually resorted to impressment—compulsory enlistment in which trained sailors were forcibly seized from merchant ships far and wide, as well as from terrified fishing communities and other settlements along the rivers and coasts of Britain, including the city of London on the Thames River. American merchant ships were at times targeted in these manpower raids, particularly as thousands of British seamen (many of them deserters from the Royal Navy) were known to work on board American merchantmen, attracted by the better pay and conditions and the reduced likelihood of encountering a Royal Navy press gang. Some British sailors also enlisted with the U.S. Navy.

The Royal Navy insisted on the right to board American and other neutral merchant ships, even on the high seas, to impress British citizens and remove deserters. To the Americans, this was nothing less than a violation of their sovereignty.

If British seamen had been the only ones taken from American vessels, there might have been much less rancor, but British ship captains also claimed many Americans. One problem was deciding who was an American, because at that time there was no marked American accent. Certificates of citizenship were issued to many American seamen to prevent them from being seized by press gangs, but British citizens could easily purchase bogus protection documents, both in America and in major British seaports, so the Royal Navy tended to treat them all with suspicion.

While the United States granted citizenship to immigrants, Britain held that nationality could not be renounced unless by permission of that nation. This meant that anyone born in the British Isles could not escape the obligation of serving in the navy simply by becoming a naturalized American citizen. The Royal Navy therefore believed that it had the right to impress anyone who spoke English, resulting in thousands of Americans being mistakenly—or deliberately—seized. It has been estimated that from the start of the war with France in 1793 to the outbreak of war with America, between eight and ten thousand American seamen were impressed into the Royal Navy, while others served as volunteers.

Although war between the United States and Britain did not start until 1812, an incident five years earlier almost led to an outbreak of hostilities. In June 1807, the British warships Bellona, Leopard, and Melampus were lying in wait in Lynnhaven Bay, just inside the Chesapeake Bay. They were hoping to intercept two French seventy-four-gun ships of the line, Patriote and Eole, which had been part of the squadron of Rear Admiral Jean-Baptiste-Philibert Willaumez that had taken refuge there nearly a year before, after being damaged by a severe hurricane. The British flotilla, setting up a blockade to keep an eye on these warships, regularly anchored in Hampton Roads to obtain provisions and fresh water in the port of Norfolk.

During the first part of 1807, the British had problems with men deserting from their warships whenever they could seize the opportunity. In one such incident in February 1807, five seamen deserted the frigate Melampus, moored in Hampton Roads, while its officers were entertaining guests. They then enlisted with the American frigate Chesapeake, which was fitting out at the Washington Navy Yard. The men included William Ware, Daniel Martin, and John Strachan. A report described what happened: “While the Officers were engaged and all the Ship’s boat except the captain’s gig hoisted in, they and two other men availed themselves of the opportunity to seize the gig and row off. That as soon as they got into the boat, they were hailed to know what they were going to do: they replied they were going ashore. A brisk fire of musketry instantly commenced from the ship; but in defiance of the danger and at the hazard of their lives, they continued to row and finally effected their escape to Sewell’s point.”

In another incident the following month, five more sailors deserted, this time from the sloop HMS Halifax. Under cover of thick fog, they seized control of the sloop’s jolly boat and threatened to murder the midshipman in charge. When they reached shore, the sailors, one of whom was Jenkin Ratford, joined the U.S. Navy under assumed names. Complaining about all the deserters, the British exchanged considerable correspondence with various American authorities.

To make matters worse, British officers frequently saw the five deserters in Norfolk, which increased their irritation at being unable to recover them. On one occasion, the captain of Halifax met two deserters, including Ratford, on a Norfolk street and asked them to return. The captain wrote that Ratford retorted “with abuse and oaths, that he was in the land of liberty and would do as he liked.”

When nothing was done to return any of the seamen, the matter was taken up with Vice-Admiral Sir George Cranfield Berkeley, commander of the British squadron, who was based at Halifax, Nova Scotia. At the beginning of June 1807, he issued an order to his captains to search Chesapeake for deserters if the American frigate was met “at sea, and without the limits of the United States.” In turn, Berkeley ordered, if the Americans made a similar demand, they should be allowed to search for any deserters, “according to the usages of civilized nations on terms of peace and amity with each other.”

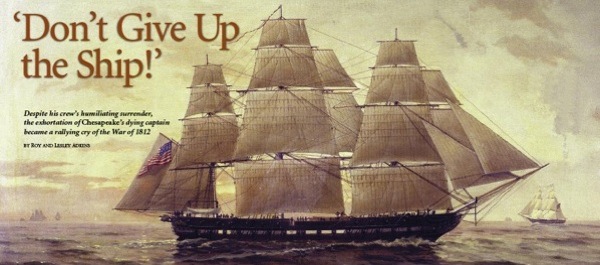

Chesapeake was supposed to head for the Mediterranean to relieve the frigate Constitution, which had been away since August 1803—nearly four years. Constitution’s crew should have already returned home and been paid their wages, so its men were disgruntled over the delays in fitting out its sister frigate. In early June, Chesapeake was at long last ready to sail down the Potomac River to Norfolk, where it still needed to be provisioned. This included fitting further guns and loading stores and water, all of which was completed on June 19. Three days later, on the 22nd, Chesapeake sailed into the Atlantic under the command of Commodore James Barron, with Captain Charles Gordon in charge of the ship. It carried a crew of nearly four hundred men and boys, as well as several passengers. They sailed past two of the anchored British warships, Bellona and Melampus. As the United States was not at war, it was of no concern that Chesapeake’s decks were strewn with stores and lumber, that little had been stowed away, and that the crew had never practiced firing the guns.

The British frigate Leopard, under Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys, had moved farther out to sea, well beyond American waters, and in midafternoon it approached Chesapeake, signaling that it had dispatches. Although a boat from Leopard—a foreign warship—was allowed alongside, Commodore Barron did not call his men to quarters, a common practice if there was no obvious threat.

Lieutenant John Meade boarded Chesapeake and was shown to Barron’s cabin. There he presented him with Vice-Admiral Berkeley’s orders, which complained that “many seamen, subjects of his Britannic Majesty…while at anchor in the Chesapeake, deserted and entered on board the United States frigate called the ‘Chesapeake,’ and openly paraded the streets of Norfolk, in the sight of their officers, under the American flag, protected by the magistrates of the town and the recruiting officer belonging to the above-mentioned American frigate.”

Barron claimed that he knew of no such deserters and that he had given instructions not to enlist deserters. Furthermore, he refused point-blank to allow a search for these men. Barron obviously felt uneasy at the belligerent tone of the dispatches, so as Lieutenant Meade returned to Leopard, he ordered his officers to quietly call the men to quarters, clear the gun deck, and prepare for action. They had hardly begun when the British frigate fired two warning shots across Chesapeake’s bow and stern, followed by three devastating broadsides from a distance of less than two hundred feet.

The two ships were evenly matched in terms of firepower, but Chesapeake had a much larger crew. However, the American gun crews could not return fire because, even though the guns were loaded, they had neither lighted matches nor red-hot irons. Already British cannons had caused much damage to the hull, sails, and rigging, with three men killed and eighteen wounded, including Barron himself. After just fifteen minutes, the commodore decided to surrender rather than risk further massacre of his men, but Chesapeake had yet to fire a single cannon in retaliation.

The two ships were evenly matched in terms of firepower, but Chesapeake had a much larger crew. However, the American gun crews could not return fire because, even though the guns were loaded, they had neither lighted matches nor red-hot irons. Already British cannons had caused much damage to the hull, sails, and rigging, with three men killed and eighteen wounded, including Barron himself. After just fifteen minutes, the commodore decided to surrender rather than risk further massacre of his men, but Chesapeake had yet to fire a single cannon in retaliation.

Barron kept calling for one gun to be fired before he surrendered, as was customary to save the honor of a ship, so that it could not be said to have surrendered without firing a shot. At the very moment he finally ordered the flag hauled down, Chesapeake managed to fire a single gun. The third lieutenant, William Henry Allen, had heroically carried a burning coal from the galley in his hands.

HMS Leopard ceased firing and sent a boat to the frigate with several lieutenants and other officers, including Marine Sergeant James Atkins, who noted that “the American officers presented their swords which, however, Britons refused to accept; we mustered the ship’s company and found many English in their service but as our orders were only to secure deserters, we in consequence secured only 4 belonging to the Melampus.” How many of Chesapeake’s crew were British, and how many of those were Royal Navy deserters, remains uncertain, but Atkins made it clear that the British followed Admiral Berkeley’s orders to remove deserters only, and that merely a handful could be identified—three (not four) from Melampus and one from Halifax.

Thirty-four-year-old Jenkin Ratford of Halifax had enlisted with Chesapeake under the assumed name of John Wilson. He was now dragged from his hiding place and put on board Leopard. The other three men—John Strachan, Daniel Martin, and William Ware—were in fact Americans. They had originally been illegally pressed into the Royal Navy, only to return to their merchant ships and then desert again, this time joining Melampus as volunteers.

Commodore Barron sent Captain Humphreys a letter stating that the American frigate was now his prize, but the British declined to take the ship. The captain declared that “having to the utmost of my power fulfilled the instructions of my commander-in-chief, I have nothing more to desire, and must in consequence proceed to join the remainder of the squadron.”

Barron rejected Humphreys’ offers of help, and the battered Chesapeake limped back to Norfolk, the crew working furiously to pump out water that was already several feet deep in the hold. Marine Sergeant Atkins contemptuously wrote that “we had the satisfaction of seeing the poor Yankee…return past us again, skulking close into the shore like a dog with his tail burnt and with nothing appearing but his sides well hammered.”

On July 1, Commodore Stephen Decatur took command of Chesapeake. The following day President Thomas Jefferson ordered all British warships to leave American waters.

At Halifax on August 26, the court-martial of the three Melampus men and the deserter Ratford took place. Vice-Admiral Berkeley ordered the three Americans to receive five hundred lashes each, though the punishment was never carried out. Instead, the sailors were held in prison, where William Ware died. The other two were returned to Chesapeake in 1812. Ratford “was found guilty of mutiny, desertion, and contempt, and hanged at the fore yard-arm of the Halifax, the ship from which he had deserted.”

United States citizens reacted with outrage and shame at what had happened. Public meetings were held in many places, and some of Norfolk’s residents rioted, smashing water casks belonging to the British squadron. Crowds demanded war with Britain; indeed, many of the British anticipated war.

Both sides made attempts to resolve the issue, the British disavowing Admiral Berkeley’s decision to fire on Chesapeake. The Admiralty recalled him to England, and his fellow Royal Navy officers expressed horror at the unprovoked attack on a warship. Vice-Admiral Lord Cuthbert Collingwood wrote from his flagship, the ninety-eight-gun HMS Ocean, based off Syracuse in Sicily, that “the affair in America I consider as exceedingly improvident and unfortunate, as in the issue it may involve us in a contest which it would be wisdom to avoid. When English seamen can be recovered in a quiet way, it is well; but when demanded as a national right, which must be enforced, we should be prepared to do reciprocal justice. In the return [report] I have, from only part of the ships, there are 217 Americans. Would it be judicious to expose ourselves to a call for them?”

Still, Great Britain did continue to assert its right to search American merchant vessels for deserters. On October 16, its government issued a proclamation that ordered all British seamen engaged in the service of foreign vessels and foreign states to return home and instructed all British naval officers to seize any such seamen. It also reinforced the right of impressment from foreign merchant vessels, but disclaimed the right to search naval ships of other nations. All of this increased American ire.

In early 1808 Commodore Barron was court-martialed at Norfolk, on board his former ship, Chesapeake. Found guilty of failing to call his men to quarters when Leopard approached, he was suspended without pay from the U.S. Navy for five years and spent the time abroad, taking no part in the subsequent war against Britain. (Stephen Decatur had been a friend of Barron’s, but was among the trial judges. In 1820 Barron would kill Decatur in a duel stemming from the incident.)

Increasingly provoked by the issues of impressment and continuing interference with trade, the United States declared war on Britain in June 1812. Since Trafalgar, the overconfident British had become lax in training their crews, particularly in gunnery. They were shocked to encounter determined and skillful American opposition, as well as a few superior frigates. From an early stage in the war, the Royal Navy suffered humiliating defeats, such as USS Constitution’s capture of HMS Guerriere, and USS United States taking HMS Macedonian. The British people, shocked and disillusioned, wondered what had become of their once universally victorious navy.

British Captain Charles Napier commented, “I cannot help observing that the Americans owed their success in a great degree to our Government and naval officers holding them too cheap, and instead of sending out large and well-manned frigates to crush them at once, we trusted to our supposed naval superiority….We unfortunately considered them far below the French in naval knowledge and gunnery, when they were actually superior to ourselves, having devoted much attention to that science, which we had shamefully neglected.” The Admiralty in London, though, responded by implementing an effective counterstrategy—using their superior numbers to blockade American ports.

The blockade started at a low level in 1812, but by February 1813 more British warships were available, and an effective blockade covered the Atlantic coast from the Delaware to the Chesapeake. The ports of New England were spared at this stage, as their merchants were supplying grain for the Duke of Wellington’s troops fighting in Spain and Portugal. Licensed American merchantmen carried this vital cargo under the Royal Navy’s protection. The British also hoped that such a selective blockade would increase the dissension between the Northeastern states, which had opposed the war, and the rest of the United States.

Already some American frigates were so securely trapped in port that they would take no further part in the war. Others were forced to wait weeks or months before they found an opportunity to slip out to sea. Toward the end of March 1813, the blockade was extended farther south and as far north as New York, and gradually the stranglehold was completed.

After being damaged in 1807, Chesapeake had been repaired and continued in service, but with little success and a growing reputation as an unlucky ship. In April 1813 the frigate reached Boston after a cruise, and many of the crew were paid off. Several of the officers were sick, including the captain. James Lawrence, whose previous command, Hornet, had recently sunk the brig HMS Peacock, replaced him. Lawrence joined Chesapeake in May, when the ship was nearly ready to put to sea again—except that the British were now blockading Boston Harbor. At the end of April, two frigates—President and Congress—had successfully eluded the British frigates Shannon and Tenedos, escaping from Boston into the Atlantic, much to the consternation of the Admiralty. Only Chesapeake remained at Boston.

After being damaged in 1807, Chesapeake had been repaired and continued in service, but with little success and a growing reputation as an unlucky ship. In April 1813 the frigate reached Boston after a cruise, and many of the crew were paid off. Several of the officers were sick, including the captain. James Lawrence, whose previous command, Hornet, had recently sunk the brig HMS Peacock, replaced him. Lawrence joined Chesapeake in May, when the ship was nearly ready to put to sea again—except that the British were now blockading Boston Harbor. At the end of April, two frigates—President and Congress—had successfully eluded the British frigates Shannon and Tenedos, escaping from Boston into the Atlantic, much to the consternation of the Admiralty. Only Chesapeake remained at Boston.

Captain Philip Bowes Broke commanded the blockading thirty-eight-gun Shannon. He had been with the frigate nearly seven years, and was unusually diligent about instilling discipline. Broke was constantly training his men in all forms of gunnery, using floating targets such as empty beef casks. Gunnery was his passion, and he introduced many innovations and adaptations for Shannon’s guns. While blockading the harbor, Captain Broke captured several merchant ships, but he burned these rather than take them back to Halifax as prizes, so as not to deplete Shannon’s crew. At a dinner hosted in London that summer of 1813 by the artist Joseph Farington, one naval captain, a guest, remarked (as Farington recorded in his diary): “Capn. Broke he was much acquainted with—that he was a remarkably good-natured man, and was always laughing. He had his mind long bent upon capturing an American frigate & that to keep the complement of men in his ship compleat, he burnt whatever prizes he took, not regarding their value. His ship was a pattern of perfect discipline, & his men were much attached to him.”

Toward the end of May, everyone on board Shannon was worried that Chesapeake would try to slip away under cover of the thick fog they were experiencing. All that changed on the first day of June, as Lieutenant Provo Wallis later recalled: “For some days previous to the 1st June…the weather in Boston Bay had been very thick and foggy, so much so that we had to guess our position. The morning of the above-named day, however, was ushered in by a brilliant sunrise, and the land near Boston sighted; but we were not without fear lest the Chesapeake had effected her escape during the thick weather….

Having, however, stood in to reconnoiter, we were gratified by a sight of her at anchor in Nantasket Roads, a sure proof that she was ready for sea.”

With the greatly improved weather, Captain Lawrence wrote to the American secretary of the navy: “I have been detained for want of men. I am now getting under weigh [sic]….An English frigate is now in sight from my deck. I have sent a pilot boat out to reconnoiter, and should she be alone I am in hopes to give a good account of her before night. My crew appear to be in fine spirits, and, I trust, will do their duty.”

Shannon maintained the blockade alone because the seventy-four-gun warship La Hogue had gone to Halifax for supplies and Captain Broke had sent Tenedos farther away, to set up a one-on-one contest between Shannon and Chesapeake. The two frigates were evenly matched, but although Lawrence claimed in his letter that his men were in fine spirits, they had rarely practiced together, and some of the officers were still incapacitated by sickness. It was a crew, but not a trained team of skilled fighters.

Captain Broke decided to send a challenge to Captain Lawrence: “Sir, As the Chesapeake appears now ready for sea, I request you will do me the favor to meet the Shannon with her, ship to ship, to try the fortune of our respective flags.” He informed Lawrence that he had sent away other ships of his squadron so that the duel between them would be fair, and then gave him details of the crew and armament of his ship: “The Shannon mounts 24 guns upon her broadside, and one light boat gun; 18-pounders on her main deck, and 32-pound carronades on her quarter-deck and forecastle; and is manned with a complement of 300 men and boys, (a large proportion of the latter), besides 30 seamen, boys, and passengers, who were taken out of recaptured vessels lately.”

Captain Broke decided to send a challenge to Captain Lawrence: “Sir, As the Chesapeake appears now ready for sea, I request you will do me the favor to meet the Shannon with her, ship to ship, to try the fortune of our respective flags.” He informed Lawrence that he had sent away other ships of his squadron so that the duel between them would be fair, and then gave him details of the crew and armament of his ship: “The Shannon mounts 24 guns upon her broadside, and one light boat gun; 18-pounders on her main deck, and 32-pound carronades on her quarter-deck and forecastle; and is manned with a complement of 300 men and boys, (a large proportion of the latter), besides 30 seamen, boys, and passengers, who were taken out of recaptured vessels lately.”

He added: “You must, Sir, be aware that my proposals are highly advantageous to you, as you cannot proceed to sea singly in the Chesapeake, without imminent risk of being crushed by the superior force of the numerous British squadrons which are now abroad….Choose your terms—but let us meet.” On the envelope of the letter he wrote, “We have thirteen American prisoners on board, which I will give you for as many British sailors, if you will send them out; otherwise, being privateers-men, they must be detained.”

The letter never reached Lawrence. Inexplicably, he had already decided to risk an encounter rather than slip away under cover of poor weather or darkness, as the other two frigates had done. He left Boston at midday on Tuesday, June 1, even though Chesapeake was completely unprepared for action. On shore, there was an expectation of imminent success, and crowds of people gathered to watch. It was reported that “so confident were the Americans of victory, that a number of pleasure-boats came out with the Chesapeake from Boston, to see the Shannon compelled to strike; and a grand dinner was actually preparing on shore for the Chesapeake’s officers, against their return with the prize!”

“I took a position between Cape Ann and Cape Cod,” Captain Broke later wrote, “and then hove to for him to join us—the enemy came down in a very handsome manner, having three American ensigns flying.” Broke addressed his men: “Shannons! The Americans have, owing to the disparity in force, captured several of our frigates; but to-day, I trust, they will find out the stuff British sailors are made of when upon an equality. I feel sure you will all do your duty. In a word—remember, you have some hundreds of your brother sailors’ blood to avenge!”

One seaman then asked him: “Mayn’t we have three ensigns, sir, like she has?” “No,” said Broke, “we’ve always been an unassuming ship.” Unusually, he also prohibited cheering, insisting on silence as they headed into battle.

All Chesapeake’s guns had stirring names, engraved on copper plates, including “Yankee Protection,” “Liberty for Ever,” “America,” and “Washington.” While they approached Shannon, Lawrence tried to encourage his men further with the words “Peacock her, my lads! Peacock her!” referring to Hornet’s destruction of that ship.

About twenty miles from Boston, at half past five that afternoon, Chesapeake met Shannon. They exchanged two or three broadsides, but from the first, the training of Shannon’s men proved devastating. Lieutenant Augustus Ludlow, acting first lieutenant of Chesapeake, remarked, “Of one hundred and fifty men quartered on the upper deck, I did not see fifty on their feet after the first fire.”

Marksmen high up in Shannon’s rigging reckoned “that the hammocks, splinters, and wrecks of all kinds driven across the deck formed a complete cloud.” The two ships became so entangled that Chesapeake could no longer fire at Shannon. Lawrence gave orders to board the British ship, but in vain. He was hit by a musket ball from one of the topmen and carried below. Before he left the deck, his last words were: “Tell the men to fire faster and not give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks!” A modified version of this would serve as a rallying cry for the U.S. Navy: “Don’t give up the ship!

According to Lieutenant Wallis, Captain Broke quickly assessed the situation and decided to board Chesapeake: “Broke, who saw the confusion on board of her, ran forward, calling out, ‘Follow me who can’ and jumped on board, supported by all who were within hearing [about fifty seamen and marines]. A minute had hardly elapsed before the ships had separated, and a general cry was then raised, ‘Cease firing,’ and by the time I had got upon the quarterdeck from the aftermost part of our maindeck the ships had got so far asunder that it was impossible to throw any more men on board of her; but it was unnecessary, as they hailed, ‘We have possession.’”

The gallantry of Broke’s men was noteworthy, but their casualties were high, not least from friendly fire. Broke later wrote, regretfully: “My brave First Lieutenant, Mr. Watt, was slain in the moment of victory, in the act of hoisting the British colors; his death is a severe loss to the service.” While they were hauling down the American colors and replacing them with the British flag, Lieutenant George Watt and some of the men surrounding him had been fired on by Shannon men, who mistook them for Americans.

Broke himself was lucky to survive. “Having received a severe saber wound at the first onset whilst charging a party of the enemy who had rallied on their forecastle,” he remarked, “I was only capable of giving command till assured our conquest was complete, and then directing Second Lieutenant Wallis to take charge of the Shannon, and secure the prisoners.” Wallis explained, “My first care was to get the prisoners secured, which was an easy matter, as the Chesapeake had (upon deck) some hundreds of handcuffs in readiness for us.”

The Americans had been so sure of victory they were planning a triumphant return to Boston with Shannon’s crew in handcuffs. The battle had indeed been one-sided, but not in the direction the Americans anticipated. It gained the dubious distinction of being the quickest slaughter in naval history up to then, as it was all over in eleven minutes. At least sixty-one crewmen were killed and eighty-five injured from Chesapeake, while from Shannon thirty-four were killed and fifty-two injured. With a prize crew and prisoners on board, Chesapeake left Boston and headed for Nova Scotia, accompanied by Shannon. The ships reached Halifax on June 5, but thick fog forced them to wait outside the harbor until the 6th, a Sunday.

Some fifty years later, the author and judge Thomas Chandler Haliburton recalled the events that day: “I was attending divine service in St. Paul’s Church at that time, when a person was seen to enter hurriedly, whisper something to a friend in the garrison pew, and as hastily withdraw. The effect was electrical, for, whatever the news was, it flew from pew to pew, and one by one, the congregation left the church.

“My own impression was that there was a fire in the immediate vicinity of St. Paul’s; and the movement soon became so general that I, too, left the building to inquire into the cause of the commotion. I was informed by a person in the crowd than ‘an English man-of-war was coming up the harbor with an American frigate as her prize.’ By that time the ships were in full view, near George’s Island, and slowly moving through the water. Every housetop and every wharf was crowded with groups of excited people, and, as the ships successively passed, they were greeted with vociferous cheers. Halifax was never in such a state of excitement before or since.”

Haliburton and a friend found a boat and rowed out to Shannon, but were denied admission. Instead, they were allowed to board Chesapeake, and because the vessel only had a small prize crew, the carnage of battle had not yet been removed. Haliburton remembered the grim scene: “Externally she looked…as if just returned from a short cruise; but internally the scene was one never to be forgotten by a landsman….The coils and folds of ropes were steeped in gore as if in a slaughter-house. She was a fir-built ship, and her splinters had wounded nearly as many men as Shannon’s shot. Pieces of skin, with pendant hair, were adhering to the sides of the ship; and in one place I noticed portions of fingers protruding, as if thrust through the outer wall of the frigate; while several of the sailors, to whom liquor had evidently been handed through the portholes by visitors in boats, were lying asleep on the bloody floor as if they had fallen in action and had expired where they lay. Altogether, it was a scene of devastation as difficult to forget as to describe. It is one of the most painful reminiscences of my youth, for I was but seventeen years of age.”

Once Captain Broke was taken off Shannon, the surgeon of the naval hospital examined him: “I was requested…to visit Captain Broke, confined to bed at the commissioner’s house in the dockyard, and found him in a very weak state, with an extensive saber wound on the side of the head, the brain exposed to view for three inches or more; he was unable to converse, save in monosyllables.” Miraculously, he survived and returned to England in October. He would never serve at sea again, and although he lived to the age of sixty-four, he never fully regained his health.

Captain Lawrence survived four days, but died of his wounds on June 5, just before they reached Halifax. He was thirty-one years old. His body was wrapped in Chesapeake’s flag and laid on the quarterdeck, before being buried with military honors at Halifax.

Lieutenant Ludlow, acting first lieutenant of Chesapeake, made reasonable progress, but died a few days after being transferred to the naval hospital, and was buried close to Lawrence. He was only twenty-one years old. His own last words were “Don’t give up the ship.”

When news reached America of the death of these two officers, Captain George Crowninshield from Salem, Massachusetts, called for their bodies to be brought back to the United States. He was given permission to sail with a flag of truce to Halifax, and on August 13 returned to America with the two bodies. At Salem, a further funeral service took place, attended by thousands of people. The coffins were then taken to New York, where some fifty thousand people watched the procession, and where a third funeral service took place, this time in Trinity Church. Lawrence and Ludlow were buried together in Trinity churchyard. In 1847 their remains were removed closer to Broadway, and a new, imposing mausoleum was erected in the Trinity Church graveyard, where it can still be seen.

The news had been slow to spread through America, but Richard Rush, comptroller of the treasury, later wrote: “I remember…the first rumor of it. I remember the startling sensation. I remember, at first, the universal incredulity. I remember how the post offices were thronged for successive days with anxious thousands; how collections of citizens rode out for miles on the highway, accosting the mail to catch something by anticipation. At last, when the certainty was known, I remember the public gloom; funeral orations, badges of mourning, bespoke it. ‘Don’t give up the ship!’ the dying words of Lawrence…were on every tongue.”

In Britain, there was widespread public celebration at the news, with guns fired, illuminations, bonfires, and numerous speeches. Broke was knighted and showered with other honors and gifts, and in Parliament, John Croker, secretary of the Admiralty, said that “the action, which he fought with Chesapeake, was in every respect unexampled. It was not—and he knew it was a bold assertion which he made—to be surpassed by any engagement which graced the naval annals of Great Britain.”

Chesapeake was brought to England and served in the Royal Navy until 1819, when it was sold for dismantling. Its final fate was described by a vicar of Fareham, near Portsmouth, who heard the story from Joshua Holmes, a builder: “She was sold by Government to Mr. Holmes for £500, who found he had made a capital investment on this occasion, and cleared £1,000 profit. He broke up the vessel, took several tons of copper from her, and disposed of the timbers, which were quite new and sound, of beautiful pitch pine, for building purposes. Much of the wood was employed in building houses in Portsmouth; but a large portion was sold, in 1820, to Mr. John Prior, a miller, of Wickham, for nearly £200. Mr. Prior pulled down his own mill, and constructed a new one with this timber, which he found admirably adapted to this purpose.”

The watermill in Wickham became known as Chesapeake Mill and operated until 1970. Extensive historical and archaeological research has recently taken place to investigate the mill, which is one of the finest surviving buildings constructed from old ship timbers.

In America, the British blockade only intensified, but the military, worn out by its exertions against Napoleon, never really mounted an effective invasion. Both nations were eager for peace after half-hearted British attempts were made against Washington and Baltimore in the summer of 1814. The treaty ending the war was signed on December 24, but a British army, unaware of this, made a final, ill-fated assault on New Orleans on January 8, 1815. The British also came to grudgingly respect the U.S. Navy. MHQ