Iran will build a bomb when it’s ready, despite treaty restrictions

After nine years of negotiating, the United States, Iran and five other nations—Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—signed an agreement in July 2015 in Vienna lifting international trade sanctions on Iran in return for restrictions on its nuclear program: Research and development is capped for 10 years, and enrichment of uranium is limited for 15.

President Obama praised the deal as an example of “strong and disciplined diplomacy,” and the UN Security Council voted its unanimous approval. But critics hammered what they believe are the agreement’s flaws: Foreign inspectors must give 24 days’ notice before they visit Iranian nuclear facilities, ample time to hide evidence of any violation; and with Iran’s path to an atomic bomb ensured (if slowed), its rivals in the Islamic world may try to build their own bombs.

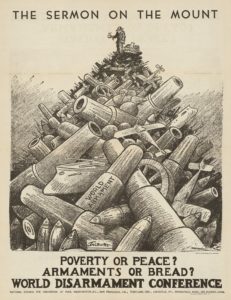

The United States has a long history of seeking peace through disarmament. Isolation from Europe, and an aversion to taxes, encouraged military cutbacks after each of the country’s early wars. At the end of the 19th century the U.S. began building up its Navy, and in 1917 it entered the World War. But once peace came, the country reverted to its old attitudes—and hoped the rest of the world would adopt them.

After the armistice Senator Hiram Johnson, R-Calif., expressed the traditional pro-disarmament view: “War may be banished from the earth more nearly by disarmament than by any other agency or in any other manner.” In December 1920 Senator William Borah, R-Idaho, proposed a practical disarmament policy: a Senate resolution asking the world’s three largest naval powers—the United States, Britain and Japan—to cut their shipbuilding in half over the next five years.

Borah’s resolution quickly caught on. Do-good groups, such as the Federal Council of Churches and the League of Women Voters, naturally supported it. But so did war hero General John J. Pershing, who argued that unless armaments were cut, the world would plunge “headlong down…to darkness and barbarism.” In May 1921 the Borah resolution passed the Senate 74-0; in July it passed the House 332-4. Disarmament gave Republicans, who had taken the lead in keeping the United States out of the League of Nations, a foreign policy that went beyond naysaying.

On Armistice Day, November 11, 1921, President Warren G. Harding dedicated the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. In an emotional ceremony that included the interment of the unidentified remains of an American serviceman who had died in the World War, the president said, “With all my heart, I wish we might say…that no such sacrifice shall be asked again.” The next day he opened a disarmament conference with representatives from Japan, Britain and six other countries. The American delegation included Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, Senate majority leader Henry Cabot Lodge, R-Mass., and Senate minority leader Oscar Underwood, D-Ala.

Harding made a lofty appeal for “less preparation for war and more enjoyment of fortunate peace,” but Secretary Hughes stunned the assembly with “a practicable program which shall at once be put into execution”: a 10-year moratorium on building capital ships, an American offer to scrap 30 battleships, a challenge to Britain and Japan together to scrap 36, and a proposal that the ratio of America’s, Britain’s and Japan’s remaining battleship tonnage be set at 5-5-3, respectively. Esteemed journalist William Allen White later called it “the most intensely dramatic moment” he had ever witnessed in his career.

Hughes had more to deal with than naval disarmament. Since 1902 the Anglo-Japanese Alliance had protected the interests of both nations in Asia. But the United States feared the alliance might quash American plans for the region. Hughes wanted to break the alliance and keep the U.S. out of any new coalitions. (In the aftermath of the World War, with its complicated political and kinship ties, Thomas Jefferson’s old warning against “entangling alliances” seemed especially pertinent.)

The Anglo-Japanese Alliance had served both parties well, but Britain considered American friendship even more vital and was willing to let the alliance go. Japan had wanted a higher battleship tonnage ratio but accepted the cuts because they still allowed the Japanese to maintain dominance in the western Pacific. (Britain and the United States had to spread their fleets over several oceans.) Hughes agreed that any future problems would be discussed with the other powers, but he refused to commit the United States to any particular actions. Hughes was mindful that any treaty he negotiated would have to be approved by two-thirds of the Senate, but he expected Lodge and Underwood to secure enough votes from among their colleagues.

By February 1922 the conference had proposed four major treaties: One covered naval disarmament, two recognized China’s sovereignty (a hedge against Japan’s aggression toward its regional rival), and one pledged that the United States, Britain, Japan and France (which controlled Indochina) would consult on future crises. The Senate ratified all four treaties, and Senator Samuel Shortridge, R-Calif., declared that “the very angels sang in joy” over the strides the conference had made toward peace in the world.

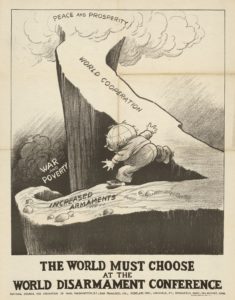

How did naval disarmament fare after the Washington conference? A treaty lasts only as long as its signatories choose to honor it. (John Jay put the point bluntly in  1782 when he called treaties “parchment securit[ies]” that “had never signified anything since the world began.”) The major naval powers met for a second time in London in 1930 and signed an agreement limiting construction of battle cruisers. But in the midst of a third conference in 1935, the Japanese walked out. Militarists were in power in Tokyo and spurned foreign directives. For more than a dozen years the United States and Britain had avoided an expensive arms race, but when a second World War broke out in 1939 both countries found their navies weakened. As historian Paul Kennedy put it, the democracies “ignored until the very last moment the possibility that…pacifistic inclinations might not be shared by others.” The U.S. Navy, thanks to America’s industrial capacity, was able to catch up, even after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, but Britain’s never truly did.

1782 when he called treaties “parchment securit[ies]” that “had never signified anything since the world began.”) The major naval powers met for a second time in London in 1930 and signed an agreement limiting construction of battle cruisers. But in the midst of a third conference in 1935, the Japanese walked out. Militarists were in power in Tokyo and spurned foreign directives. For more than a dozen years the United States and Britain had avoided an expensive arms race, but when a second World War broke out in 1939 both countries found their navies weakened. As historian Paul Kennedy put it, the democracies “ignored until the very last moment the possibility that…pacifistic inclinations might not be shared by others.” The U.S. Navy, thanks to America’s industrial capacity, was able to catch up, even after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, but Britain’s never truly did.

President Harding and Secretary Hughes had guaranteed Senate approval of the Washington conference treaties by sending Senators Lodge and Underwood as negotiators. President Obama neutralized the Senate by making the Iran deal an executive agreement, not a treaty. Any attempt by Congress to block it would have to override a presidential veto.

But the Iran deal shares the limitation of all treaties—it will last only as long as the parties want it to. General Martin Dempsey, Obama’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, acknowledged as much when he told the Senate Armed Services Committee in July that “time and Iranian behavior will determine if the nuclear agreement is effective and sustainable.” And if the angels will continue to sing in joy.

Richard Brookhiser is a historian and a columnist for the National Review.

[hr]

This column appeared in the December 2015 issue of American History.