It looked like curtains for the crew of the lumbering Spectre gunship as the surface-to-air missiles closed in for the kill.

We slaughtered ’em. As that night’s first AC-130 Spectre gunship into Laos, we found trucks everywhere. In less than three hours we destroyed 21 and wrecked 15. Inside a booth in the gunship’s belly, we sensor operators felt as if we had been given free passes to a shooting gallery. I ran the low-light-level TV sensor on most missions, but that night I was giving on-the-job combat training to Major Ed Coogan. He had no other place to learn the trade; the dozen Spectre gunships flying out of Ubon Royal Thai Air Base were the only ones in the world.

On his first mission, Coogan excitedly guided the attack, practically tripping over targets and setting fire to most of what he found. Having the time of his life, he grinned and shouted, “Is it always like this?” I nodded, thinking to myself, soon he’d learn there was no Santa Claus.

With an hour of on-target fuel and a couple hundred 40mm rounds remaining, we broke into laughter when Major Jim Ballsmith used the electronic magic of his Black Crow sensor to lead us to 16 more vehicles. We were on our way to chalking up our highest one-night score of the 1970-71 dry season.

The sight of so many untouched trucks keyed Coogan to an even higher pitch. He jerked the TV’s electronic crosshairs toward a truck and called out, “TV tracking!”

The infrared sensor (IR) operator, Captain Lee Schuiten, looked back at me and started to speak, but sucked on a tooth instead. I shrugged, and then suggested to Coogan, “Maybe you ought to take a break.”

“No,” he said, “I’m fine.” Tightening his grip on the TV joystick, he hunched his shoulders like a dog guarding a bone.

Looking into his eyes, I saw nothing but flaming trucks. He was hooked. “I thought maybe you’d like to have Schuiten track targets for a while,” I said.

“No,” Coogan said. Focused on the television picture, he was floating in a world of pure adrenalin.

Unwritten booth etiquette demanded that the TV and IR operators shared in tracking targets, when possible. After all, that was the fun part of the mission. Perhaps I had failed to explain booth protocol properly, I decided. So I drew a breath and hollered: “Hey, Coogan, you’ve shot 36 f—in’ trucks in a row. How ’bout giving Schuiten his turn.”

Less than a minute later, with Coogan apologizing and Schuiten now happily tracking, our pilot Major Ed Holley set fire to a convoy leader. Major Dick Kauffman, the navigator seated behind the pilots on the flight deck, best described the next several minutes:

“Lam Son 719 was in progress and we were not allowed to fly east of Tchepone at the time. A lot of truck traffic was trying to end-run the push on the ground. The triple-A was pretty intense. The trucks Ballsmith found were in two groups, about three miles apart, around five miles southwest of Tchepone. When we pounded the south group, multiple triple-A guns started up. I decided we could hold orbit maybe three or so turns before breaking off and attacking the north group. I thought that if we stayed in orbit any longer the gunners would start aiming where they expected us to be. I intended to vary the number of orbits we spent on each group. We moved back and forth between the two groups and destroyed or damaged a lot of the trucks.”

Coogan would later say: “I knew I was an FNG [f—ing new guy] without reference points, but I still couldn’t believe the intensity of the triple-A. I kept hoping it wasn’t going to be like this on every mission.”

About then, Our Lady of Loreto or Saint Therese of Lisieux, or Saint Joseph of Cupertino, or whichever bony relic supposedly protected the living flesh of fliers, snoozed off at the switch. Working a new truck, Major Holley fired one round—“Ka-ping”—as if clearing his throat. But, in that short pause before he followed with his usual lethal burst of three, Ballsmith said, “I have a SAM activity light.”

Holley’s burst never came. Nobody spoke.

SAM was Death.

“I have a SAM activity light,” Ballsmith repeated with conviction, as if trying to convince himself as much as the rest of the crew. The scope display on his Radar Homing and Warning (RHAW) gear indicated that a missile launch site was tracking our slow-moving, high-winged, four-engine airplane. This was the worst imaginable mismatch of the war. “Turn to a heading of two-seven-zero,” Major Ballsmith said as he locked his unblinking eyes on the RHAW gear.

Holley turned to the heading, putting the radar tracking site behind us, and then rammed the airspeed up to 185 knots. He said, “Are you pos—”

“I have a SAM ready-to-launch light,” Ballsmith announced.

Everyone aboard the gunship froze.

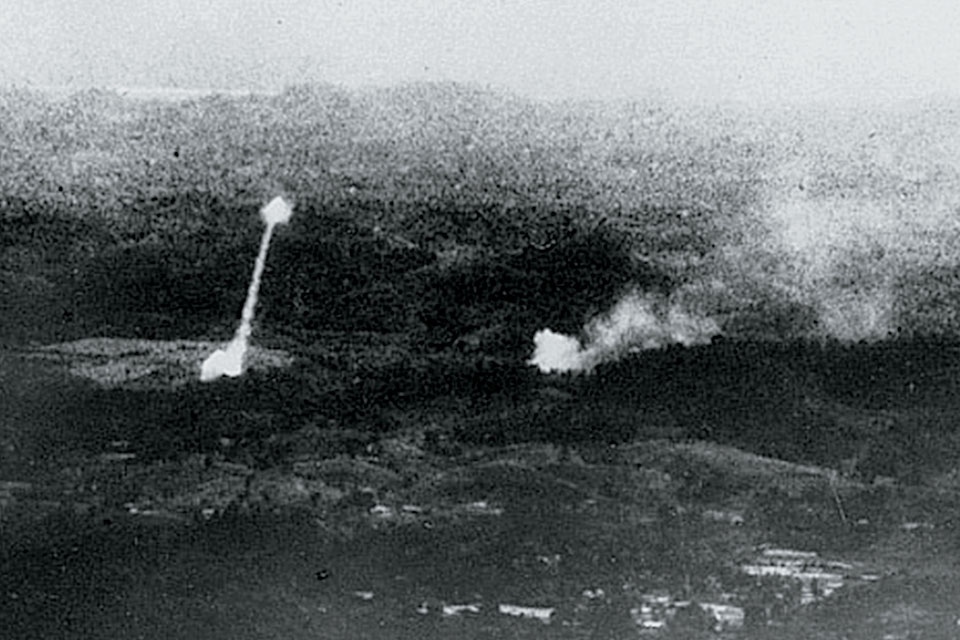

The SAM (surface-to-air missile) employed in Southeast Asia was the Soviet-built SA-2 (NATO code name “Guideline”), which, once it got humming, reached twice the speed of sound. Ground radar (code name “Fan Song”) guided the missile. An SA-2’s 300-pound high explosive warhead detonated upon impact, or upon command of a Fan Song operator.

The SA-2 had been designed for use against high performance aircraft—fast movers. A lot of swift F-4 Phantoms had outmaneuvered SA-2s. But there were also a lot of them who had watched the missile eat their lunch. The turkey we were in was no match for missiles. Our predicament seemed akin to drifting along in an old South Sea steamer and suddenly being attacked by a torpedo-firing nuclear submarine.

Every flier knew that North Vietnam was stacked wall-to-wall with SAM sites. However, up to that date—March 2, 1971—no SA-2s had been detected in Laos. United States Air Force intelligence publications declared that the Guideline had “poor cross-country ability and would not be expected to be deployed in forward areas.” Could be North Vietnamese planners failed to read those reports.

To better understand everything that was happening, I pulled out all the control buttons on my intercom box. At once I could hear the high-pitched rattle, similar to a continuous whine, of the ground radar that had homed in on us.

During training I had frequently listened to tape recordings of ground radar activity. First came the short mid-range squeaks, several seconds apart, of the normal 360- degree search scan; each time the radar beam passed over the airplane, the RHAW gear picked up and converted its energy to light signals, for the Black Crow sensor to read, and also to sounds, for the other crewmen to hear. When radar tracked the airplane, its sweep narrowed to a few degrees as it painted back and forth across the target; in the airplane, the RHAW gear squeaks became higher pitched and more frequent, occurring every second. When the ground radar scan narrowed to approximately one degree for aiming a missile, the RHAW gear picked up a high-pitched rattle. Instructors had likened the sound to a rattlesnake’s warning immediately before it strikes.

“I have a SAM launch light!” Ballsmith said loudly and clearly. The signal indicated that a missile had been fired at the gunship.

“Ohhhhh,” somebody moaned over the interphone.

Kauffman later told me:

“I could hardly believe how fast the enemy radar got on us with sweep location and an altitude finder. We were working the northern group of trucks when all of a sudden they barrage-fired every gun down there. As we started to dance around the fire, the SAM radar came up and transitioned from low to high rate within seconds. Then Ballsmith called launch.”

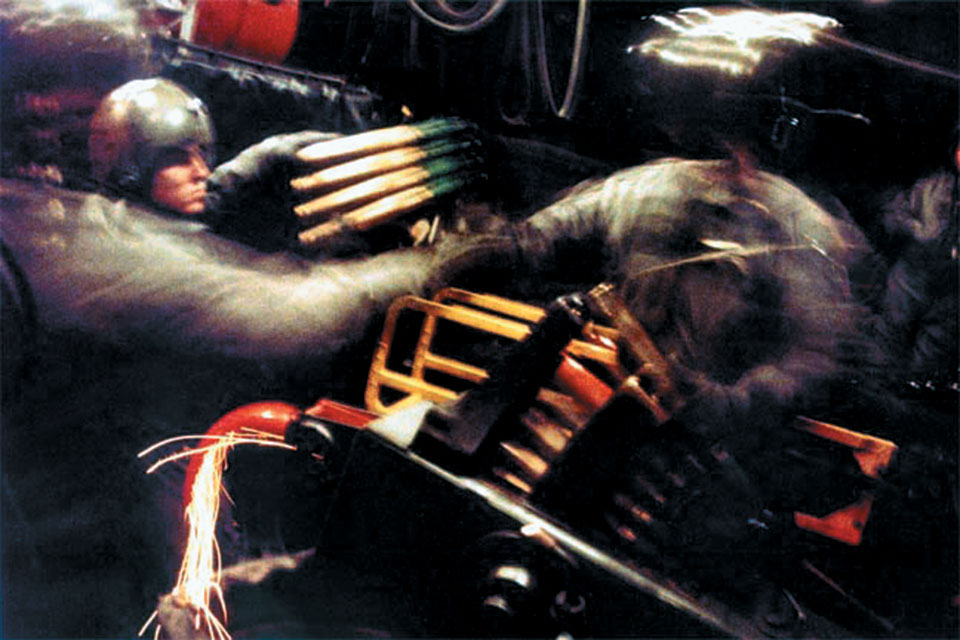

Stretched out on the open aft cargo ramp and acting like a pair of eyes in the back of the pilot’s head, Staff Sgt. Bob Savage searched in the blackness of the night. A moment after Ballsmith’s “SAM launch” call, he reported: “I saw a flash, 6 o’clock. Six to eight, maybe 10 miles.” Held by a thin steel safety line, Savage leaned far beyond the edge of the ramp until he hung partially airborne in the aircraft’s slipstream. “I saw another flash!” he shouted over the interphone, “think it was separation.” The SA-2 had two stages: liquid-propelled and a solid fuel booster. Suddenly Savage clearly recognized the missile engine’s fire. “I see it!” he shouted. “It’s climbing!” He watched the flames for several seconds. “Turn right, sir,” he said. Holley banked hard right, and a moment later Savage said: “It turned with us. Left! Break left, sir!” Holley rolled hard to the left and again the missile turned with him. Savage shouted, “It’s leveling off, headed this way!”

I looked at Coogan and grinned. The fire in his eyes had flickered out. Santa Claus was dead.

“It’s coming straight at us!” Savage yelled. He later recalled how he had read accounts by fighter pilots who had described Guidelines as “the size of telephone poles.” When you were nose to nose with one of the big white bastards, the missile was huge. “It’s coming straight at us!” he warned. “It’s coming right in the ramp! Dive! Dive! Dive!”

“Hang on,” Holley said, “we’re going down!”

There have been great moments in sports when the man transcended the moment by calling his shot. Remember? The Babe pointing to the stands before belting a World Series homer; Broadway Joe predicting Super Bowl victory; time and time again, Ali naming the knockout round: Those feats gave rise to immortality. But no such feat ever related to cheating death, calling the shot with premeditated certainty. And that was what Holley was about to try: He intended to snatch 14 souls from the gates of hell—exactly as he had once told us he would!

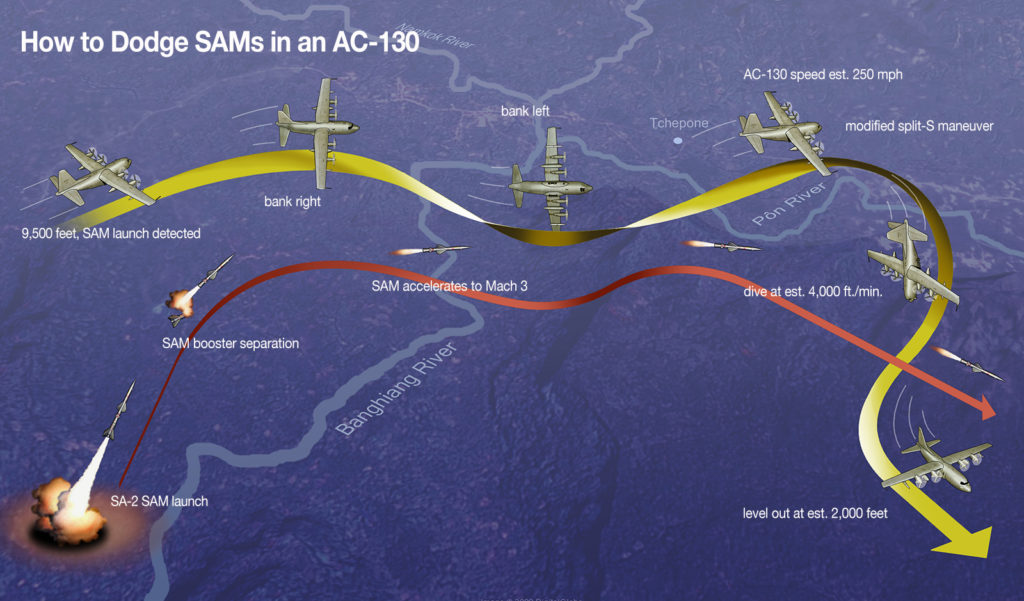

Based on instrument readings in the booth, from an altitude of 9,500 feet, Holley rolled the gunship into a 135-degree bank, practically upside down, and then arced the nose earthward in a 4,000- foot-per-minute dive. The maneuver was like turning over a dump truck and still expecting to steer it. Our turkey wasn’t designed for such a feat. Yet Holley did it. Maintaining a positive one-gravity load on the creaky, antiquated airframe, he plunged downward in open defiance of several laws of aerodynamics.

On the flight deck, Kauffman viewed the maneuver from a different perspective: “We had already turned away from the source. I had logged our position. When Sergeant Savage said, ‘Dive,’ Ed immediately started a roll to the right. I was staring at the attitude gyro and watched it passing 90 degrees of bank. A few seconds later we passed a 120-degree of bank when the gyro failed. I was calling barometric altimeter readings. I had the radar altimeter on and noted the height above the terrain at the start of the descent. When the gyro failed I looked at the radar altimeter and it had no pulse to indicate height. I assumed it was looking sideways or upward. Shortly thereafter the electrical generators started failing and we were on battery power at least up front. We pulled out, according to the barometric altimeter, at between 1,500 and 2,000 feet. The ground elevation was 600 feet in the area. Our heading was approximately 180 degrees’ difference from when we started the roll.”

Throughout the maneuver, Kauffman’s soothing voice spoke only to Holley: “Maximum terrain elevation is 3,100 feet,” which meant that somewhere in the general area below us a chunk of karst jutted up that high. Acting as if he knew there definitely was a tomorrow, Kauffman calmly read the altitudes as we vertically flashed through them: “Eighty-five hundred feet…8,000 feet…7,500 feet….” Gertrude Stein once wrote, “A rose is a rose is a rose.” Had she described Holley and Kauffman in tandem, she would have said: “Cool is cool is cool. And then some.”

While Kauffman tolled the altitudes, I shouted at Coogan, “Don’t give up yet!” I didn’t know what he thought, but I put little faith in my words. I found it difficult to believe what we were doing. I aimlessly tapped the altitude indicator. The airplane did not have ejection seats. The crew had no choice but to ride it out.

Holley’s maneuver was termed a “split-S.” He had explained its use one morning over breakfast when the crew had been playing “What if…?” Thinking the unthinkable, I had asked, “What if they launch a SAM at us?” Everyone at the table had laughed, except Holley. Without hesitation he had said: “I’ll dive and turn into it. The maneuver works for fighters. No reason it can’t work for us.” He had been irritated when his answer brought more laughter. “I can do anything with a 130 that you can do with a jet,” he had boldly proclaimed, “only I do it lower and slower and tighter. I can escape from a SAM.”

He had called his shot. And now, incredibly, he was taking it— maybe, I thought.

I also recalled a conversation with a pilot who had flown with Holley in Alaska. He had said: “I’ve watched Ed land resupply flights in total whiteouts. In that situation, there’s no sky or ground or horizon—nothing to see or guide by. It’s all done on confidence and instinct. Ed’s the best Herky pilot in the business—on wheels or skis or anything you can name.”

Now, fixated on the unwinding altimeter, I wondered how many men had sat in exactly the same manner, expecting to be hit by a missile—ground-to-air or air-to-air—and unable to do anything except wait it out. I decided that a lot of guys had died that way. Right before it happened, they probably had thought exactly what I was thinking: This could be the end.

Seconds passed like minutes. It seemed as if Ballsmith had made his warning calls hours earlier. I looked at Coogan and grinned again, but my gut felt hollow. The altimeter seemed to unwind in slow motion but its numbers stopped registering in my mind. We all hung suspended in an aerodynamic world of Holley’s creation.

Involuntarily, I hunched my shoulders, contracted my neck and lowered my head. After long moments, I became aware of my reactions and looked up. The three other men in the booth had struck similar motionless poses. I realized I was holding my breath and wondered about the others. I expected death but, at the same time, felt no fear of dying. I didn’t hope or pray.

Then the plane felt as if it were leveling off, and after what seemed to be a long silence, Holley asked: “Bob? Anybody? You see it?”

“No, sir,” Bob Savage said softly. “I think it went over top of us.”

Somewhere that big deadly son of a bitch was still chugging along in the dark.

Holley eased the gunship’s nose above the horizon and started a climb back to 9,500 feet. He had outflown the most fearsome threat—the sparrow had escaped the hawk. “Nice work, Sergeant Savage,” he said convincingly, “Very nice work. You too, Major Ballsmith. You too. Great work.” He spoke to Kauffman without calling him by name: “Think you can find that last convoy again?” Kauffman instantly gave him a heading. Holley said, “What do you think, gang, want to finish off those trucks?” It was a rhetorical question.

Coogan asked me, “Should we be working around out here any more tonight?”

I shrugged: Never pass up a piece….

“That had to be an SA-2,” Ballsmith said.

“Affirmative, sir,” Savage said. “It looked just like the pictures.”

“How long did that take?” Kauffman asked.

I said, “About 45 minutes.”

Schuiten corrected me: “More like 45 seconds.”

“Seemed like an hour and a half to me!” I shouted at Coogan off interphone, and I meant it.

He waved a hand irritably, as if dismissing me. “How come you were grinning like that? You think it was funny?”

“No,” I said. “Except when we all hunched over—you know….”

“We should be coming up on that intersection,” Kauffman said. “You see it, sensors?”

“IR has it.”

“TV has the trucks. TV tracking.”

“Put IR in the computer,” Holley said. He rolled into a 30-degree left bank, intercepted the firing orbit, and opened up with a 40mm. Rounds impacted near the last truck in line.

Schuiten said, “You hit—”

“Good God!” Ballsmith shouted, “I have another SAM activity light. Turn to three-zero-zero.”

I looked at Coogan and tried not to grin, but I couldn’t control my face. “Here we go again,” I said. Coogan said something that I didn’t hear and tightened the leg straps on his parachute.

This part of the mission is impossible to comprehend—even today, even if I live to be 100. What made us go back? Gallantry? Arrogance? Ignorance? We later learned that simultaneous with the first missile launch against us, another missile made a head-on pass at another gunship. For some reason, that crew didn’t detect Fan Song activity, and they had no inkling of being under attack until the SA-2 loomed in front of the cockpit. Before the pilots could react, the missile streaked over the gunship and disappeared back into the night. That crew had broadcast SAM launch warnings and—except for us—all aircraft evacuated the Steel Tiger section of Laos. Meanwhile, occupied with our own missile, we simply failed to hear the message and remained oblivious to the other activity.

Holley turned to Ballsmith’s new escape heading, and we went through the same sequence of events as in the first attack: “Ready-to-launch light,” then “Launch light.” Savage reported: “I have two flashes!” He narrated the flight of the two missiles in a dull monotone, and I wondered if he was in shock, or if practice just made perfect. Holley executed the same evasive maneuver.

“You believe this shit?” I shouted at Coogan.

“I don’t like any of it!” he said. Under his eyes were bags that would have qualified as two-suiters. I could not imagine what I looked like.

Although events followed the same script, to me everything happened more rapidly, yet in finer detail. It was like sitting through a movie that I’d seen before. Somehow, the action lacked a feeling of reality. I couldn’t believe we actually were doing it all again. My mind tried to tell me that I was seeing a replay of the first time, or that now was merely a continuation of the first time. I suppose I couldn’t believe that we had encountered—had stupidly walked into—the identical trap, twice within such a short period of time. More than anything, I just wanted it to end. Yet I felt as if I knew the outcome, since I’d seen this movie before. My mind and central nervous system felt short-circuited.

Both SA-2s missed—of course! Our copilot Captain Mike Scott believed he saw them detonate in the distance, far beyond us, out of range. This time, Holley headed home to Ubon, flying at low level.

The booth became a madhouse. The gunners and scanners piled in and everyone shouted and beat on Savage. Several times he said, “I don’t think those last two were guided very well.”

Coogan began to look a little brighter. I fed him food for thought: “What do you think the odds are against doing what we did—against doing what we did twice?”

He shook his head. Frowning, he asked me, “Is it like this every mission?”

I grinned. “No,” I said. “Sometimes it’s a lot worse.”

Of course, Lam Son 719 was a perfect time for the NVA to sneak SA-2 Guidelines into Steel Tiger. Our intelligence experts had focused on the area east of Tchepone, thereby somewhat dismissing activity northward. Consequently, intelligence officers had provided aircrews with no warning of an NVA SAM deployment. In fact, one of Ed Coogan’s sharpest memories of the night concerned our crew debriefing. He said:

“I vividly remember the after-mission briefing when the so-called intel people tried to talk us out of what we experienced. The tape the Black Crow had of the rattlesnake warning of the SAM acquisition radar may have helped convince them that we were truly at tacked by SAMs. I remember how hard the intel people worked to discredit the eyewitness reports of the IO, scanners, and other crew members. Intel simply did not want to admit that they had been outsmarted.”

Rumors later made the rounds that the North Vietnamese air force had planned to sneak a couple of MIGs into Steel Tiger to shoot down a Spectre gunship, but it never happened.

Well after the event, Dick Kauffman may have had the final word on the issue. Reassigned to Seventh Air Force at Tan Son Nhut during the dry season, he researched every intelligence report he could find for the two months before March 2, 1971. He discovered one report that talked of SA-2s and their launchers being moved into the general area around Tchepone a week before we were attacked. As far as he could determine, nobody ever passed the information to aircrews. He also learned that according to Seventh Air Force planners, a 50 percent loss rate for the AC-130 during the 1970-71 dry season had been calculated as acceptable. “No one ever asked me if that was acceptable,” Kauffman said.

The morning after we escaped the SAMs, Kauffman, with whom I roomed, said: “I still can’t believe any of it. Ed split-S’ed. Twice! I don’t know if he actually rolled exactly 180 to complete a perfect split-S, but what he did was good enough to have the missiles go over the top of us.What really amazed me was that I didn’t have my seat belt on and I never came out of the chair. Ed held a positive one G throughout the whole thing. He is really outstanding.”

“Ed’s the champ,” I said. “Undefeated.” Thirteen troops owed him their lives. What more could anyone say?

—Henry Zeybel flew 772 C-130 sorties in Vietnam and 158 AC-130 missions in Laos and Cambodia. He was awarded the Silver Star, eight Distinguished Flying Crosses and 19 Air Medals. He served a third tour as the Special Operations Forces liaison officer.

This feature was originally published in the April 2009 issue of Vietnam Magazine. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe!