‘An injudicious and censurable act’ was how Justice Wells Spicer described Virgil Earp’s decision to involve the notorious gambler in a deadly street fight.

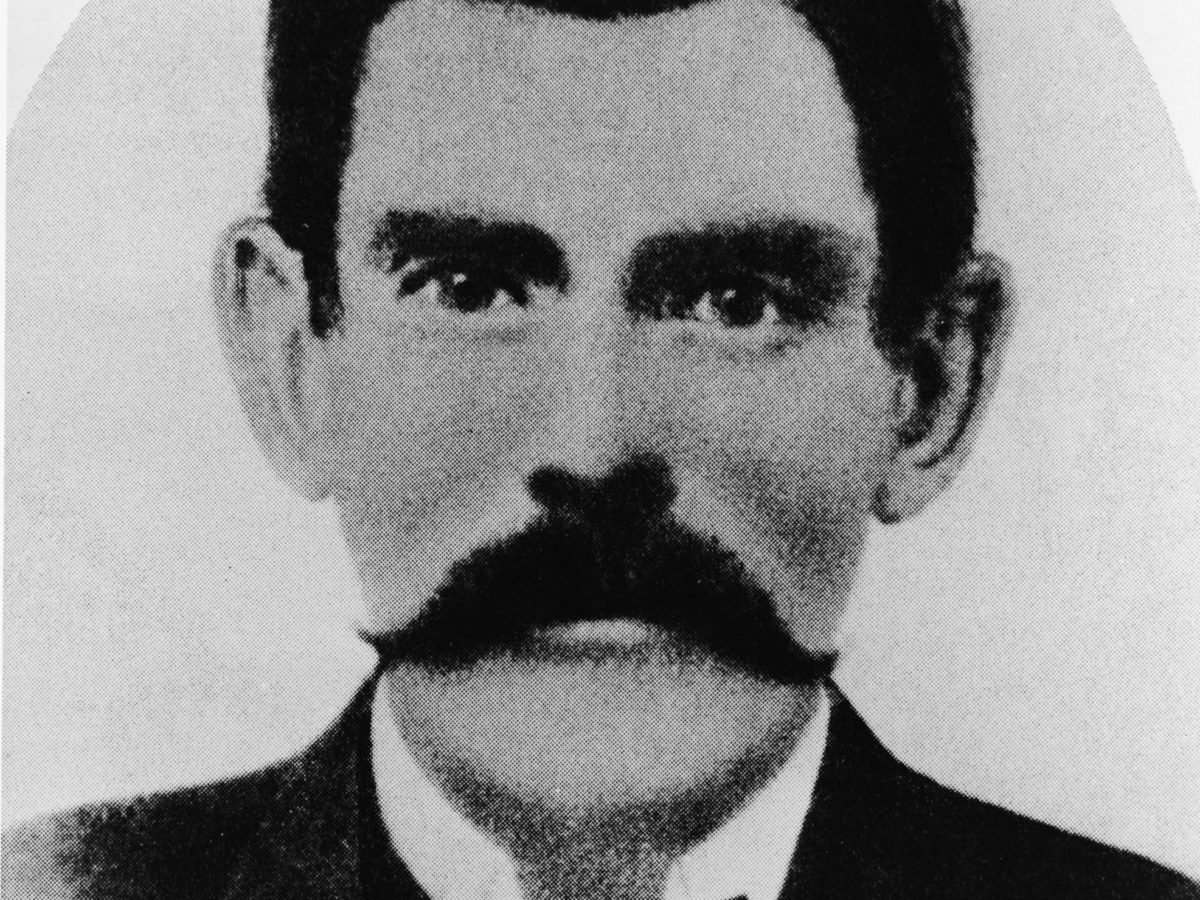

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, on October 26, 1881, John Henry “Doc” Holliday joined the Earp brothers, Virgil, Wyatt and Morgan, on their walk into legend down Tombstone, Arizona Territory’s Fremont Street to the fateful encounter remembered as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Thereafter, the names of Doc Holliday and the Earps were inexorably linked. As soon as it was over, the bloody affray was lost in controversy, remembered both as the triumph of law over outlaw and as senseless murder. Beyond the facts— how many died, how many shots were fired, who fired first and why—the gunfight took on mythic symbolism.

One of the chief reasons for controversy was the presence of Doc Holliday. Virgil Earp was chief of police (sometimes called marshal) in Tombstone, and his brothers, Wyatt and Morgan, held special positions as law officers, but Holliday was a gambler of less than spotless reputation who had quarreled with one of the men in the other party only the night before. His involvement exposed the chief of police to hard questions about why he called on Holliday for assistance.

The deaths of Tom and Frank McLaury and young Billy Clanton that cold October afternoon led to a hearing to determine whether the Earps and Doc Holliday should be tried for murder. Throughout those proceedings before Justice Wells Spicer, Holliday’s actions and reputation were issues. The defense, which was headed by attorney Tom Fitch, managed to convince Spicer that Holliday was not a central factor in the fight, but Holliday’s role would remain an issue in both contemporary debate over the fight and in the historical controversy it spawned.

Recommended for you

Justice Spicer handed down his decision in the case on December 1, 1881, after a month of testimony, and while he discharged the defendants because he found insufficient evidence to warrant a conviction, he did observe that Virgil Earp, in calling upon his brother Wyatt and Doc Holliday to assist him, “committed an injudicious and censurable act.” (Wyatt, like Doc, had had an encounter with one of the Cowboys prior to the fight.) Spicer added that in view of the circumstances surrounding the fight, he could “attach no criminality to his unwise act.” He then observed, “In fact, as the result plainly proves, he needed the assistance and support of staunch and true friends, upon whose courage, coolness and fidelity he could depend, in case of an emergency.”

The controversy was largely a matter of reputation. To understand Holliday’s role in the affair and the impact he had on public perception of the case requires some review of the events that led to the fateful encounter. When he came to Tombstone in 1880, he was simply one more “well-known sport” among many well-known sports. That changed not long after he arrived when he had a quarrel with another gambler, Johnny Tyler, at the Oriental Saloon. Milt Joyce, one of the owners of the Oriental, prevented a fight between Holliday and Tyler, but Doc, who was intoxicated at the time, returned to the saloon to demand his pistol. When Joyce refused, Doc left, secured another pistol and went back to the saloon once again. Holliday opened fire, striking Joyce in the hand and wounding his partner, and was beaten severely by the saloon keeper.

Not only did the incident make Doc an enemy of Milt Joyce (who would later serve on the Cochise County Board of Supervisors), but Doc’s friendship with Wyatt Earp also soured Joyce on the Earps. After the incident with Doc, Joyce was prepared to believe the worst about them, and more important, he would be in a position to use his influence against them. That proved important later.

On March 15, 1881, road agents attempted to rob the Benson stage near Drew’s Station, and in the botched affair they killed the stage driver, Eli “Bud” Philpott, and a passenger, Peter Roerig. The robbers were quickly identified as William Leonard, Harry Head, Jim Crane and Luther King. King was arrested but escaped under peculiar circumstances; the others eluded the posses that set out to catch them.

Because of Doc’s friendship with Bill Leonard—whom he had known at Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory, before coming to Tombstone—and his admitted presence at Leonard’s place earlier on the afternoon before the robbery, Holliday became a suspect in the case, although no charges were filed at the time.

In early July 1881, following a quarrel with Doc, his mistress, Kate Elder, accused him of being involved in the robbery attempt. Sheriff John Behan and Holliday’s bête noir, Milt Joyce, encouraged Elder to bring charges against Doc, and he was arrested for murder and attempted stage robbery. Kate was also arrested by Virgil Earp for being drunk and disorderly immediately following Doc’s incarceration. Kate’s sworn affidavit accusing Doc of complicity in the affair has not been found, so the question of exactly what she said remains unanswered. When Kate sobered up, she may have repudiated her affidavit. In any case, she was fined, and the charges against Doc were quickly dropped because of insufficient evidence. For those predisposed to think the worst, however, the incident left questions unanswered.

In the meantime, Wyatt Earp, who had ambitions to be sheriff of Cochise County, had already decided that arresting the remaining Benson stage robbers was the best way to enhance his chances. He therefore entered into a secret deal with Ike Clanton, who knew the robbers, in which Clanton agreed to betray them in exchange for a Wells, Fargo & Co. reward of $3,600.

It was a daring and dangerous deal, especially for Clanton and his associates, who were par- ties to the plan because of their relationship with the would-be stage robbers and their friends. In June, before the deal could be consummated, Leonard and Head were killed, and in August Crane, the last of the suspects, was killed by Mexican soldiers at Guadalupe Canyon. The deaths of Leonard, Head and Crane left a festering secret between Wyatt Earp and Ike Clanton and eliminated any chance of removing lingering suspicions about Doc’s role in the robbery attempt.

In October 1881, Marshall Williams, the local Wells Fargo agent, while drunk, made comments to Ike Clanton that indicated he knew about Ike’s deal with Wyatt. Angered by this revelation, Clanton sought out Earp and accused him of betraying his trust. In the process, he also accused Earp of telling Doc Holliday of the plan. Earp denied that he had spoken about their deal to anyone other than the original parties to the discussion, and he told Ike that a conversation with Doc would prove him to be unaware of any deal.

Doc was out of town gambling in Tucson, so Wyatt sent his brother Morgan to get him. Before Holliday returned, however, Ike Clanton left Tombstone briefly. He returned on October 25, 1881, in the company of Tom McLaury. That night, Holliday met Clanton at the Alhambra Saloon, and denied knowledge of any deal between him and Wyatt. Their conversation quickly escalated into a noisy, threatening situation that was defused, temporarily, when Morgan Earp separated the pair. Outside the Alhambra, they continued to exchange insults until Virgil Earp intervened and threatened to arrest both parties. At that point, Ike Clanton went to the Grand Hotel and Wyatt Earp led Doc away.

Doc Holliday went to his lodgings behind C.S. Fly’s photographic studio (or gallery) and retired after that, but Ike Clanton continued to make threats not only against Holliday but against the Earps as well, threats that continued the next day until Virgil Earp, as chief of police, was awakened at home and went looking for him. When Virgil found irritable Ike roaming the streets with a rifle in hand, the chief of police struck him with a pistol and hauled him into court. A sore head and a fine did not quiet Clanton. Rather the situation escalated, especially after Wyatt Earp buffaloed Tom McLaury outside the courtroom, and Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury arrived in Tombstone.

Interestingly, Doc Holliday slept through most of the morning’s activities, until Kate Elder awakened him with the news that Ike Clanton had been at Fly’s looking for him. Doc pulled himself out of bed and said, “If God lets me live long enough to get my clothes on, he will see me.” Nevertheless, Doc did not go looking for Ike Clanton. He did speak cordially to Billy Clanton on the street, but he played no role in the day’s rising tensions until he joined Virgil, Wyatt and Morgan Earp at Hafford’s Corner Saloon near 2 o’clock that afternoon.

With the town abuzz with rumors and repeated reports from citizens to the chief of police of threats by the Clanton-McLaury crowd, Virgil made the decision to arrest them. It was Virgil who also decided to make Doc Holliday a part of the arresting party—giving Doc his sawed-off shotgun to hide under his long coat and taking Doc’s cane to appear less threatening. In light of Doc’s public quarrel with Ike Clanton the night before, this was Virgil’s first real mistake. At that moment, though, he needed someone with sand that he could depend on in a fight.

Together, the Earps and Doc Holliday marched down Fremont Street to the vacant lot next to Fly’s studio and into the West’s most famous gunfight. The deaths of Tom and Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton that afternoon caused considerable consternation in the town, and when Ike Clanton filed charges of murder against the three Earps and Doc Holliday, prosecutors immediately saw Doc as their best chance to make their case of murder.

When legal proceedings began, prosecutors quickly demonstrated that their intent was to show that the Earp party had fired upon men with their hands in the air attempting to surrender and, further, that Doc Holliday and Morgan Earp fired the first shots by prearrangement. Virgil’s record as chief of police had been excellent, and his brothers were regarded well by most of the townspeople. Doc stood at the center of the prosecution’s bull’s-eye because his reputation and his confrontation with Ike made him the most vulnerable link.

The case that Doc Holliday initiated the fight with a shot from his nickel-plated pistol did not stand up well under the defense’s cross examination or in light of the testimony of defense witnesses. In fact, taken as a whole, the testimony revealed Doc to have been a man who was surprisingly restrained and controlled on the day of the fight. No evidence was present that he was involved in the preliminary events that occurred earlier on October 26 or that he carried the previous night’s quarrel over into his behavior on the day of the showdown.

When he joined the Earps at the invitation of Virgil, everything changed, regardless of his conduct. In fairness, Holliday appeared to understand that his role was that of containment. When the Earp party reached the vacant lot on Fremont Street where the fight occurred, the Earps moved into the lot while Doc stayed in the street and took a position that blocked any effort on the part of the Clantons and McLaurys to leave the space between Fly’s and the Harwood house.

He did not fire until the fight had commenced and then remained cool as he stalked Tom McLaury, waiting for a shot with the scatter-gun he carried. After killing Tom and discarding the empty shotgun, he closed on Frank McLaury methodically, and when McLaury proclaimed, “I’ve got you now,” Doc responded: “Blaize Away! You’re a daisy if you have.”

Only at the end of the fight, after he had been grazed by a bullet, did his temper seem to flare toward Frank McLaury, as he proclaimed, “The son-of-a-bitch has shot me, and I mean to kill him.” But the fight was over, and he did not fire again. Doc had proved by his conduct why Virgil wanted him with his party.

Still, despite his measured performance in the street fight, Doc’s presence did lay Virgil open to charges of irresponsibility and misconduct. At the hearing, the prosecution used Doc’s alleged connection to the Benson robbery attempt to make more serious charges against the Earps. When Ike Clanton took the stand, he not only made claims about Doc’s participation in the failed robbery but also claimed that the Earps were partners in a criminal combine with Holliday and the street fight was an attempt to kill him because he knew too much.

Predictably, Ike denied the existence of a deal between himself and Wyatt to betray his friends. Instead, he claimed that Doc, Wyatt, Morgan and even Virgil had confessed to him that they were involved in “piping off money” from Wells Fargo and hoped to kill Leonard, Head and Crane to prevent them from exposing their illegal activities. Why all these men would choose him as Father Confessor, he could not explain.

The defense effectively dismantled Clanton’s testimony on cross-examination and shattered whatever was left of it in the defense’s own case. Even so, Clanton managed to plant doubts about the Earps in the public mind that had not been there before the street fight. Ironically, although the Earps were freed, Clanton succeeded in challenging their honesty and credibility in ways that would doom their future in Tombstone. The Benson stage robbery and Doc’s alleged role in it gave Ike the opening.

Ridgely Tilden, writing for the San Francisco Examiner after the hearing, made the anti-Earp case this way: “Doc Holliday is responsible for all of the killing, etc, in connection with what is known as the Earp-Clanton imbroglio in Arizona. He kicked up the fight, and Wyatt Earp and his brothers ‘stood in’ with him, on the score of gratitude.” Tilden was wrong in his analysis, but the fact remained that the one blemish on the Earps in Tombstone before the street fight was their association with Doc Holliday.

Wyatt Earp himself would say in 1926 that whenever his enemies in Tombstone “got a chance to hurt me over Holliday’s shoulders they would do it.” He added: “They would make a lot of talk about Doc Holliday….As they made Holliday a bad man. An awful bad man, which was wrong. He was a man that would fight if he had to.”

John P. Clum, who was mayor of Tombstone, editor of the Tombstone Epitaph, and an ally of the Earps when the street fight happened, did not like Holliday. In 1929 he wrote George H. Kelly, Arizona’s official historian, that Doc “doubtless, was a loyal friend and ‘game’ as a gambler or in a gun fight, but he was not a constructive citizen.” He added, “I have always felt if he had not been in that street battle on Dec. [sic] 26, 1881, the affair would have been relieved of much of its bitterness.”

Clum’s insight was based on his understanding of public perceptions at the time of the fight. Virgil Earp’s decision to enlist Doc Holliday’s help in his attempt to arrest the Clanton–McLaury party was, in Spicer’s words “injudicious” and “censurable,” but it was not because of Doc’s behavior in the street fight itself. In fact, there he was an asset, not a liability. Rather, using a man of questionable reputation who had been in a public quarrel with one of the men that the Earps went to arrest, opened the chief of police to immediate criticism. Perhaps more important, “over Holliday’s shoulders,” as Wyatt put it, Ike Clanton, the man actually most responsible for the street fight, managed to plant doubt in the public mind about the Earps themselves in a remarkable example of “guilt by association.”

Holliday’s participation did more than anything to magnify the street fight into a major incident that caused a shift of opinion against the Earps after the shooting. The prosecution’s argument that Doc fired the first shot was dismantled in court, but many outside the courtroom still believed it. Accusations against him involving the Benson stage robbery attempt made it easier for some of those same citizens to believe Clanton’s lies about an Earp criminal combine as well.

Doc’s loyalty to the Earps helped them to win the fight on Fremont Street and other fights that followed in the territory; the Earps’ loyalty to Doc, on the other hand, ultimately proved costly.

Gary L. Roberts, professor emeritus of history at Abraham Baldwin College in Georgia, has written more than 75 articles on Western history, as well as several books. His 2006 book Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend (see “Interview” with Roberts in this issue) is recommended for further reading, along with John Henry: The “Doc” Holliday Story, by Ben T. Traywick; and Doc Holliday: A Family Portrait, by Karen Holliday Tanner.

Originally published in the October 2006 issue of Wild West.