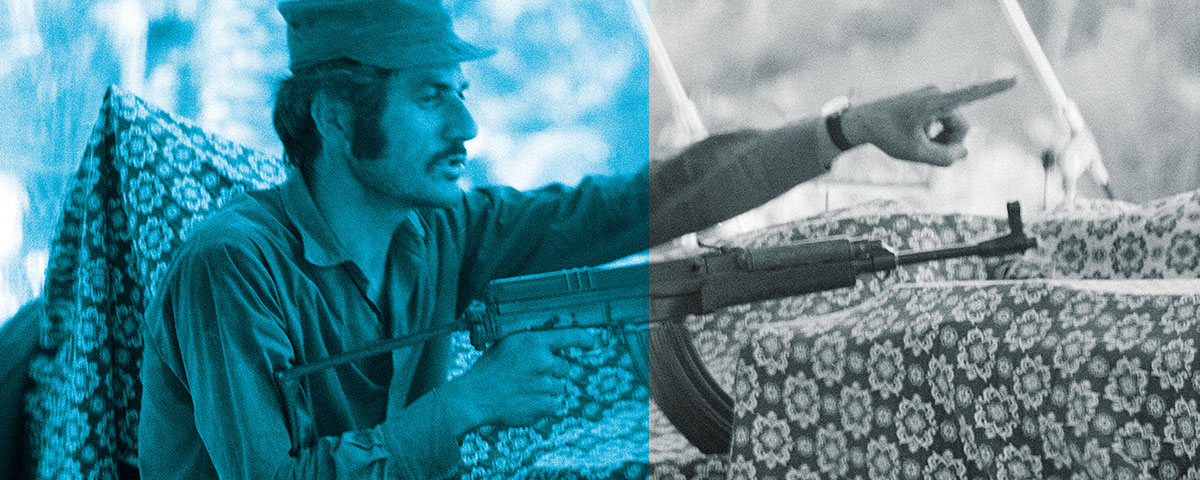

In 1974 Turkish and Greek factions took up arms on the island nation of Cyprus, sparking a divisive conflict with lasting ramifications.

His black clerical robes flapping behind him, Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios III (born Michael Christodoulou Mouskos) fled his office in Nicosia on the morning of July 15, 1974. The Cypriot National Guard, under the command of Greek officers loyal to Athens, was attacking the Presidential Palace and would largely burn it down. The “Regime of Colonels”—a junta of military officers that had overthrown King Constantine II and taken control of Greece in 1967—had sponsored the coup. It suspected Makarios of communist sympathies and was angry he had rejected enosis, the proposed political union of Cyprus into Greece, in favor of Cypriot independence. Eluding the rebelling guardsmen, the Eastern Orthodox prelate-politician made his way to his native Paphos District, on the west end of the island. The next day a Royal Air Force transport evacuated him to Malta. The exiled president flew on to London, and on July 19 he addressed the United Nations Security Council in New York regarding the coup. Meanwhile, his supporters back home refused to bow to the new regime, sparking infighting across the island.

Cyprus’ problems were only beginning.

Turkey, concerned about the population of Turks on the island and determined not to allow Cypriots to join Greece as Cretans had earlier that century, invaded on July 20. It was a short war, but one whose effects are felt to this day.

From 1878 Cyprus had been a British protectorate and colony, until gaining its independence in 1960. But by 1974 the island was a growing problem for NATO, to which both Greece and Turkey belonged. For decades the majority Greek Cypriots had pressed for enosis—the political union of Cyprus and Greece. Turkish Cypriots were understandably opposed to such a union and instead pressed for taksim—political partition of the island. Intercommunal violence had persisted since the mid-’50s.

Before the 1960 grant of independence, Greece, Turkey, Britain and members of the opposing Cypriot factions had signed agreements preventing the island nation from joining another country and dictating much of the machinery of its government. It also made Athens, Ankara and London guarantors of the accord, while also providing them a diplomatic excuse to intervene in Cypriot affairs if the treaty were abrogated. The Greek Cypriots loathed the agreements for two main reasons—they felt the accords disproportionately favored the minority Turkish Cypriots (who accounted for scarcely 20 percent of the population), and they worried the terms essentially gave Turkey a green light for military intervention.

The Greek Cypriots’ fears about a Turkish invasion were wholly warranted, for Ankara had been working on a contingency plan for landings on Cyprus since 1967. Code-named Attila, the operation foresaw landing Turkish troops on the north end of the island, then expanding the beachhead toward the largest enclave of Turkish Cypriots, near the capital city of Nicosia. The Greek Cypriots, for their part, had been planning a defense of the island for at least as long. Their operation to counter such an invasion—code-named Aphrodite—aimed to secure the Turkish Cypriot enclaves, deny the Turks supply bases and maintain a full Greek division on the island.

However, under the terms of the 1960 accords Greece had withdrawn virtually all of its troops, thus the Greek Cypriots developed a revised defense plan, Aphrodite 2, with the same basic objectives but involving a smaller body of troops drawn from the Cypriot National Guard (CNG).

The plans on either side might have remained theoretical had it not been for the Greek overthrow of Makarios III. While the exiled president’s address to the U.N. had damaged the international legitimacy of the Regime of Colonels, with the cleric temporarily out of play, the junta could more easily sway the political current on Cyprus. Athens began speaking openly of uniting Cyprus with Greece, which alarmed Ankara and the Turkish Cypriots. A few days after the coup, having failed to get London’s support in opposing the junta, Turkey invoked its guarantor status to justify an invasion. Ankara simultaneously issued an ultimatum demanding Cyprus observe the terms of the 1960 accords and permit Turkish forces on the island to protect the Turkish Cypriots while removing the few Greek troops still there.

Turkey’s posturing was no idle threat, as it had received modern U.S. military equipment in its role as a NATO bulwark against the Soviet Union. Over the course of the coming conflict, Ankara would commit those assets to the invasion of Cyprus, including M47 and M48 Patton tanks and North American F-100 Super Sabre and Lockheed F-104 Starfighter aircraft. By contrast, the 1960 accords had severely restricted Cyprus’ own military capabilities. Available forces included the CNG and a scattering of militias and paramilitary groups the Cypriots had used to agitate for independence. The sole Greek military unit on the island was the well-trained but comparatively ill-equipped Hellenic Force in Cyprus (ELDYK). The Greek Cypriots could muster perhaps 14,000 active-duty troops, but they lacked both a navy and an air force—two enormous disadvantages in a modern war—and their armored force comprised poorly maintained World War II–era Russian T-34/85 tanks. Making matters worse, at the time of the Turkish invasion Greek Cypriot forces were widely dispersed across the island, either suppressing resistance to the coup or resisting it.

On July 20 an amphibious force of 3,000 Turkish troops came ashore at Five-Mile Beach in Pentemili, west of the northern port of Kyrenia. The Turks had complete air superiority, and the only opposition they encountered on approach came from two Greek Cypriot torpedo boats. Turkish shipboard gunners sank both vessels before they could engage the flotilla.

The first Greek Cypriot troops to arrive at the Pentemili beachhead were two companies of the 251st Infantry Battalion, supported by five T-34/85 tanks. Their attack knocked out two Turkish armored personnel carriers and inflicted casualties, but the Greek Cypriots could not dislodge the Turks, and in trying lost all five of its tanks.

Simultaneously with the amphibious invasion, the Turks dropped paratroopers near Nicosia to unsettle the Greek Cypriots and secure control of the roads for the advancing main invasion force. The operation backfired, as many of the best Greek Cypriot units were in the area battling Turkish Cypriots in the Geunyeli enclave. Although unable to capture Geunyeli, the Greek Cypriots did defeat the Turkish paratroopers, capturing many and driving the rest northward. Recognizing the paratroopers would not achieve their objectives, Turkey launched heavy air attacks against CNG units in the area, inflicting substantial casualties.

Early the next morning the Turks began landing their second wave of invasion forces, including mechanized infantry and a squadron of 15 M-47 tanks. The CNG continued, with little success, its assault on Geunyeli. The Turks also continued their heavy air assaults, one of which fell victim to deception tactics. By transmitting false radio signals, the Greek Cypriot Naval Command tricked Turkish pilots into thinking a trio of its own destroyers were Greek ships coming to reinforce Cyprus. Kocatepe was sunk with the loss of 54 crewmen, while Adatepe and Tinaztepe were damaged and forced to return to port in Turkey.

That same night Athens experienced its own debacle as it sought to airlift in a battalion of Greek commandos from Crete. Greek Cypriot anti-aircraft gunners at Nicosia airport misidentified the arriving aircraft and opened fire on them. Although they shot down one transport and damaged two others, most of the commandos landed safely and were available for the defense of the airport.

Elsewhere on the island Greek Cypriots captured several small Turkish Cypriot towns, notably the Marxist enclave of Limassol, which they evacuated and promptly torched.

On July 22 the reinforced Turkish forces broke out of the bridgehead. Led by Brig. Gen. Hakki Boratas, the Bora Task Force wrested control of Kyrenia, connecting it and its harbor to the Pentemili beachhead. The Turks also pushed south, opening a corridor to Geunyeli. That prompted intense combat around the airport, and the Greek forces in Cyprus (the commandos, under Colonel Konstantinos Kombokis, and the ELDYK, under Colonel Nikolaos Nikolaidis) gave a good account of themselves. Turkish forces were nonetheless able to achieve most of their objectives by that evening, albeit hours after a U.N.-mandated cease-fire was to have started. By the time the fighting finally stopped, Turkey controlled a small but militarily useful portion of the island from Kyrenia to Geunyeli, just north of Nicosia—roughly 7 percent of Cyprus’ land area.

On July 23 the junta in Athens collapsed, in large part due to the conflict on Cyprus, and exiled political leaders began returning to the mainland the following day. That happenstance engendered a hopeful atmosphere for the peace talks being held in Geneva, thus there was little military activity on Cyprus between July 24 and August 13. The returning Greek prime minister, Konstantinos Karamanlis, opted to keep Greece out of the war, leaving Cyprus to fend for itself against Turkey should the peace talks fail. At the end of the second set of talks Turkey, feeling its position would only grow weaker, demanded Cyprus accept its plan to geographically separate Greek and Turkish Cypriots but govern them under a common federal state. The acting president of Cyprus requested time to consult with Athens and Greek Cypriot leaders, but Ankara refused, and on August 14 Turkish forces on Cyprus, which had been steadily building up, launched Operation Attila 2.

Athens’ decision to remain on the sidelines deprived the Greek Cypriots of any possible reinforcement from the mainland, though the commandos and ELDYK remained in the fight. The Turks boasted numerical superiority in nearly every respect, as control of the harbor had allowed them to bring to the island two full infantry divisions as well as armor, mechanized infantry and artillery. With that in mind the Greek Cypriots established two main defensive lines. The first faced the Turks and would be quickly overrun, so the defenders planned to inflict maximum casualties and then fall back to the Troodos line—named for the mountain range spanning the heart of the island from east to west—where they would stand and fight. While they lacked numbers, the Greek Cypriots had gained one notable advantage. Public opinion, originally with the Turks, had swung to their favor. To the world at large the underdog Greek Cypriots were far more sympathetic figures, thus the Turks had only a short operational window before they could expect outside intervention.

The Greek Cypriots had divided their first defensive line into three sectors: western, central and eastern. The central line—the shortest of the three—ran east from Nicosia airport through town to the Mia Milia suburb. The western line ran north from the airport to the coast, and the eastern from Mia Milia to the coast. The eastern line was the strongest, as the defenders expected the weight of the Turkish attack to fall there.

As expected, that attack began on the morning of the 14th with naval, air and artillery bombardment of Greek Cypriot positions along the eastern line. The Greeks responded with counterbattery fire, but not enough to deter elements of the Turkish 39th Division from advancing shortly thereafter. Though the defenders repelled the infantry assaults, the Turks quickly followed up with armored attacks that skirted the Greek minefields and broke through the sector defended by the 399th Infantry Battalion. Lacking antitank weapons, the men of the 399th fell back toward the Troodos line. To prevent a rout, CNG commanders ordered the 341st and 226th battalions to assemble a secondary defensive line, but that evening the 226th was compelled to retreat south, leaving the 341st isolated. In the central sector, after a preliminary bombardment by artillery and aircraft, Turkish units launched successive attacks against CNG and ELDYK positions around Mia Milia using a reinforced Turkish Cypriot regiment and a squadron of 17 M-48 tanks. The Turks captured a hilltop at Elissaios but gained little else, while sustaining heavy casualties.

On August 15 Greek troops in the eastern sector continued to retreat, all except the 341st Infantry Battalion, which had been reinforced by six 6-pounder guns and three T-34 tanks. Late in the day, however, its commander, given his unit’s isolated position and the approach of the Turkish 14th Infantry Regiment, ordered a retreat, covered by the T-34s. In its haste the unit left behind the tanks and 6-pounders. Meanwhile, lead Turkish units along the western line advanced nearly 4 miles, prompting Greek Cypriots in that sector to withdraw to the Troodos line.

The next day, August 16, there was little fighting in either the eastern or western sector, as Turkish units consolidated their gains of the previous two days and slowly advanced against minimal resistance. In the central sector the Turks resumed their infantry-armor push against CNG and ELDYK forces near the latter’s camp. There were heavy casualties on both sides, but by early afternoon the Turks’ numerical superiority helped them seize control of the camp. They then continued their attack into Nicosia, but were stopped by Greek Cypriot antitank and infantry fire, as well as fire from a few T-34s being used as mobile artillery.

At 6 p.m. that evening another U.N. brokered cease-fire went into effect. But as the Turks had not yet reached the Troodos line in most places, both Greek Cypriot and Turkish forces spent the next day maneuvering for position, though little fighting took place. The Greeks, conscious of their military inferiority, were not about to give up the advantages afforded them by a cease-fire, while the Turks seemingly appreciated increasing international disapproval enough to honor the cease-fire despite their military superiority. Both sides fortified their lines with trenches, mines, barbed wire and other obstacles. There were no further actions after August 18, by which point the Turks controlled just under 40 percent of the island.

By modern standards the 1974 conflict on Cyprus was short and relatively bloodless. Fewer than 80,000 troops had participated, and there was only significant fighting on six days—July 20–22 and August 14–16, though the time between July 23 and August 14 did see low-intensity combat. Total casualties were also relatively low, with fewer than 2,000 killed.

Yet the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus has cast long shadows. The island remains divided between the predominately Greek Cypriot Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The war has also been a sticking point between Turkey and Greece (and much of Europe) since the end of the conflict—a solution to the “Cyprus problem” was made a condition of Turkey’s accession to the European Union when it sought to join in the early 2000s. As it remains unrecognized by the international community at large, the Republic of Northern Cyprus relies heavily on support from Ankara. The status of Cyprus has dogged NATO, too, as the unresolved conflict between member nations only serves to weaken the alliance.

The 1974 invasion was unlike many small-scale wars in that it drew in players beyond the two main combatants, Turkey and Cyprus. The Greek junta, fearing Cypriot President Makarios was getting too cozy with the Soviets, sponsored the coup that precipitated the war. Similarly, the conflict ended not with a decisive military outcome or a truce arranged by the combatants, but because outside powers—notably the U.N. and the United States—stopped it. They trusted in politics and statesmanship to resolve the Cyprus problem—but tensions remain high on the divided island.

David Harris wrote “Father of the Navy” (January 2018), a profile of Commodore John Barry, the first commissioned officer in the U.S. Navy. For further reading he recommends Cyprus 1974: “This Ain’t No Picnic, It’s War,” by Al Gaudet, and The History and Politics of the Cyprus Conflict, by Clement Dodd.