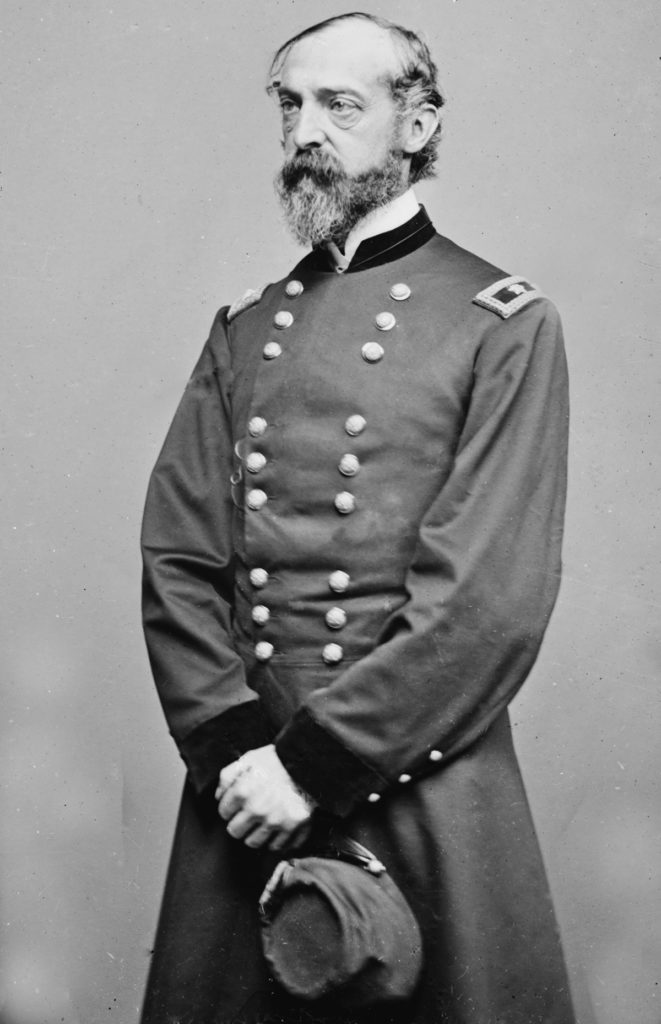

Despite the critical role Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade played in the Civil War, his historical legacy typically downplays or ignores his success on the battlefields upon which he bettered the Confederacy’s legendary General Robert E. Lee. An intelligent, hard-working, and courageous commander, Meade was wounded twice at the June 1862 Battle of Glendale, during the Seven Days Campaign, and later in the year he was in the thick of the fighting at Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. After his immediate predecessor in command of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, was humiliated at the May 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville—spurring Lee to invade Pennsylvania—President Abraham Lincoln almost literally “dumped” army command in Meade’s lap—only three days before Union and Confederate armies collided at the Battle of Gettysburg. Meade, however, would prove he was up to the challenge, leading the Union victory over Lee at Gettysburg.

Meade remained in command of the Army of the Potomac through the end of the war, fighting in all its major battles during the 1864 Overland Campaign, at the Siege of Petersburg, and, finally, victory at Appomattox. Given such notable accomplishments, why is Meade not better known and respected? Perhaps most significant were the calculated efforts of Union Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles and his subordinates to strip him of credit for defeating Lee at Gettysburg—a scheme magnified by anguish that Meade had missed a golden opportunity to destroy Lee’s army with a cautious post-battle pursuit as the Confederates retreated to Virginia. Moreover, the decision by Union Army commander-in-chief Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to establish his headquarters with Meade’s army at the outset of the Overland Campaign—Grant thereby taking direct operational as well as strategic control of the Army of the Potomac in 1864 and 1865—inevitably cast the impression that Meade was serving merely as a figurehead.

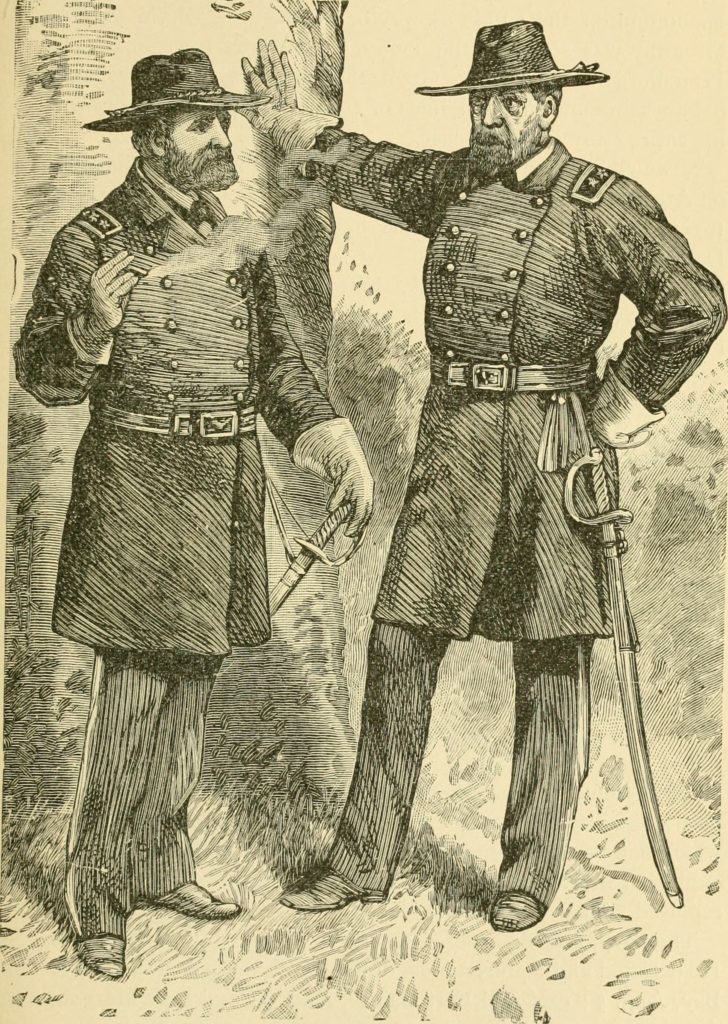

The seed for Meade’s adversity was planted on July 2, 1863—Gettysburg’s second day—when he made a lasting enemy of his 3rd Corps commander, Sickles, the disgraced but still influential congressman from New York. Disliking the contour of the land along Cemetery Ridge that Meade had assigned the 3rd Corps to defend, Sickles marched his men to what he believed was better ground three-quarters of a mile in front of the rest of Meade’s defensive line. By doing so, Sickles placed the Army of the Potomac in great peril, as his isolated corps now had both flanks unsecured, and his advance also meant that Little Round Top—critical ground on the Union’s left flank—was unprotected.

Known as “Old Snapping Turtle” for his customary dour look and volatile temper, Meade rebuked Sickles for the insubordination. But before Sickles could even consider retracing his steps, Confederates in Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s Corps attacked and the Peach Orchard and the Wheatfield were embroiled in furious fighting. Meade did not hesitate to respond, and gaps were plugged at several key points. Despite resilient Confederate pushes across the southern end of the battlefield, the Federals succeeded in preventing a Rebel breakthrough.

Famously, Sickles would soon be out of the fighting, as he was struck in the right leg near the Trostle Farm by a Confederate cannonball, necessitating its amputation.

Before Gettysburg, Meade, an 1835 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, was relatively unknown. Suddenly he was a national hero, lauded in newspapers across the North for delivering a glorious Union victory. Just 11 days later, however, the platitudes had turned mostly to outrage. Meade was being pilloried for allowing Lee’s battered and retreating army to recross the Potomac River to Virginia on July 14. It later became known that Lincoln was himself distraught at Meade’s “hesitant” pursuit of Lee and had composed a critical letter to the general that he decided to keep in his desk.

Meade would be further criticized later in the year for the outcome of the Mine Run Campaign, essentially a bloody stalemate that effectively concluded the 1863 campaign season in Virginia. Meanwhile, as he recuperated in Washington, the one-legged Sickles told as many as he could—including the president—that he had been the real hero of Gettysburg and that his unapproved advance had ultimately spoiled Lee’s battle plans, thereby saving the Army of the Potomac from destruction.

When Meade denied a request by Sickles to return to command, Sickles sought revenge. In February 1864, he went before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, a highly influential committee dominated by Radical Republicans, and gave distorted testimony that Meade had handled the army ineptly at Gettysburg—that the Union army had won a great victory despite Meade. Notably, Sickles alleged that on the battle’s second day Meade had been a coward, eager to retreat rather than fight.

Major General Abner Doubleday supported Sickles’ egregious claims by testifing that Meade had played favorites in command assignments. Doubleday in particular was bitter that Meade had ignored army seniority and not promoted him to command of the 1st Corps after its commander, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, was killed early on July 1—instead choosing Maj. Gen. John Newton as Reynolds’ replacement.

It was no secret that the Joint Committee’s Radical Republicans desperately wanted “Fighting Joe” Hooker back in command of the Army of the Potomac. The committee’s leaders, Chairman Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, demanded Lincoln dismiss Meade even before he had an opportunity to testify.

On March 6, 1864, Meade’s concern for the Sickles-led damage to his reputation was apparent in a letter to his wife, Margaret:

When I reached Washington, I was greatly surprised to find the whole town talking of certain grave charges of Generals Sickles and Doubleday, that had been made against me in their testimony before the Committee on the Conduct of the War….Mr. [Edwin M.] Stanton [Secretary of War] told me…there was and had been much pressure.…to get Hooker back in command…but there was no chance of their succeeding….The only evil that will result is the spreading over the country of certain mysterious whisperings of dreadful deficiencies on my part, the truth concerning which will never reach the thousandth part of those who hear the lies….It is a melancholy state of affairs…when persons like Sickles and Doubleday can, by distorting and twisting facts, and giving a false coloring, induce the press and public…to take away the character of a man who up to that time had stood high in their estimation.

Sickles elevated his attack on Meade when he (or a close associate) penned an anonymous article by “Historicus” in the March 12, 1864, edition of The New York Herald, the nation’s largest newspaper. Historicus condemned Meade’s handling of Gettysburg while praising the brave and brilliant Sickles. The article claimed Meade had ordered his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Dan Butterfield, to prepare an order of retreat on July 2, the battle’s second day. The Historicus piece set off a firestorm, and stories of Meade’s alleged inadequacies appeared in papers nationwide.

Meade was a proud Philadelphian, and was infuriated having his public standing shredded by Sickles, whom he considered a scoundrel. Outraged by the Historicus article, the Army of the Potomac commander wrote to the War Department on March 15, 1864, requesting an investigation:

For the past fortnight the public press of the whole country has been teeming with articles, all having for their object assaults upon my reputation as an officer, and tending to throw discredit on my operations at Gettysburg.…The prominence given to General Sickles’ operations in the enclosed communication, the labored argument to prove his good judgment and my failings, all lead me to the conclusion he is either directly or indirectly the author….As the communication contains so many statements prejudicial to my reputation, I ask that the Department ascertain whether General Sickles has authorized or endorses this communication and in the event of his replying in the affirmative I request of the President of the U.S. a court of inquiry that the whole subject may be thoroughly investigated and the truth made known.

Meade’s effort to clear his name through a War Department investigation was thwarted when Lincoln declined to order a Court of Inquiry. The president wanted Meade fighting Confederates, not a fellow general, and wrote him on March 29, 1864:

The Secretary of War has asked me to consider your request for a Court of Inquiry concerning an article that appeared in the Herald. It is quite natural that you should feel some sensibility on the subject; yet I am not impressed, nor do I think the country is impressed, with the belief that your honor demands, or the public interest demands such an Inquiry. The country knows that, at all events, you have done good services; and I believe it agrees with me that it is much better for you to be engaged in trying to do more, than to be diverted, as you necessarily would be, by a Court of Inquiry.

Lincoln’s refusal to convene a military court meant that the investigation of Sickles’ accusations would be the only one conducted by the Joint Committee. Meade monitored the ongoing hearings and was dismayed when Butterfield, a close friend of Sickles’ and Hooker’s, falsely testified about the claimed July 2 order to retreat.

Meade informed Margaret in an April 6, 1864, letter of his despair with the bias of the Joint Committee:

General [Henry] Hunt has been up to Washington and before the Committee. He says, after questioning him about the famous order of July 2, and his telling them he never heard of it, and from his position and relations with me he would certainly have heard of it, they went to work and…tried to get him to admit such an order might have been issued without him knowing anything about it. This after my testimony, and that of [Generals Gouverneur] Warren, [Winfield S.] Hancock, [John] Gibbon and Hunt, evidently proves that they are determined to convict me, in spite of testimony, and that Butterfield’s perjury is to outweigh the testimony of all others.

As he prepared for the 1864 campaign season, Meade worried about how Sickles’ attacks would affect his place in history. He entrusted a family friend to transport his sworn testimony to Margaret, telling her in an April 26, 1864, letter: “You must keep this private and sacred. If anything should happen to me, you will have the means of showing to the world what my defense was.”

In early May 1864, the Army of the Potomac commenced its spring campaign at the Battle of the Wilderness. Grant, whom Lincoln had made lieutenant general in charge of all U.S. armies, set up his headquarters within walking distance of Meade’s. As such, Grant began making strategic decisions for the Army of the Potomac. Meade didn’t confront Grant over control of his army, knowing that such infighting would be injurious to the Union cause.

As the press began writing about “Grant’s Army” and his public star faded, Meade soldiered on, working closely with Grant and doing what he could to win battles and shorten the war. Margaret, it should be no surprise, was unhappy with Grant’s ascendency over her husband.

Meade, however, defended Grant, writing her on May 23, 1864:

I am sorry you will not change your opinion of Grant, I think you expect too much of him. I don’t think he is a very magnanimous man, but I believe he is above any littleness, and whatever injustice is done to me, and it is idle to deny that my position is a very unjust one, I believe it is not intentional on his part, but arises from the force of circumstances, and from weakness inherent in human nature which compels a man to look to his own interests.

Meade’s uneasy relationship with the press turned poisonous when he expelled a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter from the Army of the Potomac camp for falsely writing that he had wanted to retreat after the Battle of the Wilderness. In retaliation, AOP war correspondents banded together and agreed to ignore Meade and only write articles that put him in a bad light. This press hostility further darkened Meade’s reputation. He poured out his frustration in a July 17, 1864, letter to Margaret.

I had a visit today from General Grant, who was the first to tell me of the attack in the Times based upon my order expelling two correspondents. Grant expressed himself very much annoyed at the injustice done to me, which he said was glaring, because my order distinctly states that it was by his direction that these men were prohibited from remaining with the army. He acknowledged there was an evident intention to hold me accountable for all that was condemned and to praise him for all that was commendable.

The press was quick to blame Meade solely for the Battle of the Crater disaster on July 30, 1864. A mine had been dug underneath the Confederate fortifications at Petersburg, filled with gunpowder, and spectacularly exploded beneath Brig. Gen. Stephen Elliott Jr.’s South Carolina Brigade. Union troops under 9th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside delayed advancing beyond the huge crater created by the explosion and were savagely counterattacked by the Confederates.

On August 9, 1864, Meade wrote Margaret of his exasperation with the press:

The attempt to implicate me in the recent fiasco was truly ridiculous. Still the public must in time be influenced by these repeated and constant attacks, however untrue and unjustifiable they may be. Have you ever thought that since the first week after Gettysburg, now more than a year, I have never been alluded to in public journals except to abuse and vilify me?

The Crater debacle attracted the attention of Congress, and four members of the Joint Committee descended on Meade’s headquarters near Petersburg to investigate. It was far from an objective inquiry. On December 20, 1864, Meade wrote Margaret:

Members of the Committee on the Conduct of the War made their appearance to investigate the Mine affair. They gave me a list of witnesses to be called, from which I saw at once that their object was to censure me, as all the officers were Burnside’s friends….I asked the committee to call before them General Hunt and Colonel Duane; these officers came out laughing, and said as soon as they began to say anything that was unfavorable to Burnside, they stopped them and said that was enough, clearly showing they only wanted to hear evidence of one kind.

The press attacks continued unabated. On October 13, 1864, The New York Independent harshly blamed Meade for Grant’s inability to defeat Lee:

The advance was arrested, the whole movement interrupted, the safety of an army imperiled, the plans of the campaign frustrated—and all because one general, whose incompetence, indecision, half-heartedness in the war have again and again been demonstrated….Let us chasten our impatient hope of victory so long as General Meade retains his hold on the gallant Army of the Potomac. He holds his place by virtue of no personal qualification, but in deference to a presumed, fictitious, perverted, political necessity, and who hangs upon the neck of General Grant like an Old Man of the Sea whom he longs to be rid of, and who he retains solely in deference to the weak complaisance of his constitutional Commander-in-Chief.

The Independent’s attack deeply troubled Meade, who found it “fiendish and malicious.” By the time he met with Grant, he was considering leaving the Army of the Potomac. On October 29, he wrote Margaret:

I told him that…I did not desire to embarrass Mr. Lincoln, nor did I wish to retain command by mere sufferance; and that, unless some measures were taken to satisfy the public and silence the persistent rumors against me, I should prefer being relieved….In all successful operations I am ignored, and the moment anything went wrong I was held wholly responsible.

To address Meade’s request for a show of public support, Grant urged Lincoln to move forward with Meade’s nomination to major general of the Regular Army. Grant had proposed William Tecumseh Sherman, Phil Sheridan, and Meade at the same time for promotion, but later asked the president to delay Meade’s promotion so he would not rank Sherman. Meade was upset when his promotion was delayed, particularly because Sheridan, whom he had clashed with when Sheridan was his Cavalry Corps commander, would rank him. At Grant’s request, Lincoln went forward with Meade’s nomination, adding a sweetener by post-dating it to August so Meade would rank Sheridan. He was happy with the president’s public endorsement, writing Margaret on November 25, 1864:

General Grant told me that…the President…had hesitated when appointing Sheridan on the very ground of its seeming injustice to me, and…at General Grant’s suggestion, ordered the Secretary to make out my appointment to August 19th, the date of the capture of the Weldon Railroad, thus making me rank Sheridan….As justice is thus finally done I am satisfied….At one thing I am particularly gratified, and that is at this evidence of Grant’s truthfulness and sincerity….I am satisfied that he is really and truly friendly to me.

The Senate confirmed Meade’s nomination to major general, but that public acknowledgment of his merits as a military leader did not improve his standing with the press. He grew despondent with the unfair coverage of the climactic Appomattox Campaign, writing Margaret on April 10, 1865:

I have seen but few newspapers since this movement commenced, and I don’t want to see any more, for they are full of falsehood, and of undue and exaggerated praise of certain individuals who take pains to be on the right side of reporters. Don’t worry yourself about this, treat it with contempt. It cannot be remedied, and we should be resigned. I don’t believe the truth ever will be known, and I have a great contempt for history. Only let the war be finished, and I returned to you and the dear children, and I will be satisfied.

Grant did not include Meade, or anyone from the Army of the Potomac, in the Appomattox Court House surrender meeting with Lee at the McLean House. The newspapers ignored his role in forcing Lee’s surrender while extolling Sheridan’s. Meade was greatly embittered at the unjust press coverage, writing Margaret on April 12, 1865:

Your indignation at the exaggerated praise given to certain officers, and the ignoring of others is quite natural. I have fully performed my duty and have done my fair share of brilliant work just completed, but if the press is determined to ignore this, and the people determined, after four years’ experience of press lying, to believe what the newspapers say, I don’t see there is anything for us but to submit and be resigned. Grant, I do not consider so criminal. With Sheridan, it is not so. His determination to absorb the credit of everything done is so manifest as to have attracted the attention of the whole army, and the truth in time will be known.

Meade died at age 56 in 1872, without writing a memoir or publicly rebuking Sickles’ falsehoods and distortions about Gettysburg. Sickles lived to 94 and continued to his death in 1914 heralding his heroics at Gettysburg while disparaging Meade’s generalship. The Joint Committee’s reports on Gettysburg and the Battle of the Crater were critical of Meade and negatively impacted his reputation. In an effort to have their ancestor’s voice heard and to balance the historical record, Meade’s son and grandson, George Meade and George Gordon Meade, published his letters in 1913 in The Life and Letters of General George Gordon Meade.

In a 1961 article, The Strange Reputation of General Meade, noted historian Edwin Coddington wrote that Sickles’ attacks on Meade “greatly contributed to an unfavorable opinion of him as a commanding general, which has persisted to this day.” Coddington concluded that, “Sickles’ persistence in continuing his feud long after Meade’s death in 1872 had deep and lasting effects on publicists and historians of the battle,” and that “Sickles achieved a large measure of success” in his campaign to sully Meade’s name.

Bruce Catton’s book Glory Road is but one example of Sickles’ success at creating a narrative where some historians deny Meade credit for his Gettysburg victory. Catton wrote that when Lincoln placed Meade in command, the troops, “in effect…had no leader,” and that Meade won the battle “chiefly because his men were incomparably good soldiers.” Historians such as Coddington and Stephen W. Sears recognize in their Gettysburg books Meade’s significant and active role in winning the battle. Sears wrote that Meade reacted to “Sickles’ folly” by making “two critical, rapid-fire decisions,” ordering reinforcements to support Sickles and dispatching Brig. Gen. Gouverneur Warren to Little Round Top to see if it was protected. Sears praised Meade for “anticipating the needs of his generals, then acting decisively to meet them.”

There are reasons other than Sickles’ vendetta that contribute to Meade not being a more prominent historical figure, including his cautious pursuit of Lee after Gettysburg, Grant’s immense presence and his unfair treatment by the press. But Coddington’s scholarship shows the paramount reason that Meade’s contributions are often overlooked was Sickles’ success in tarnishing his reputation.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.