The punishments meted out in the Lichfield courts-martial of 1946 underscored the long-held belief that military justice is far from fair.

In June 2003, four months after the United States invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein’s totalitarian regime, disturbing reports and photographs of the mistreatment and torture of Iraqi detainees in the American-controlled Abu Ghraib prison began surfacing, and pressure from the news media and human rights organizations eventually forced a full investigation. A U.S. Army report, released in February 2004, confirmed “numerous incidents of sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses” by “the military police guard force.” The torture and vile conditions at Abu Ghraib galvanized renewed armed resistance to the U.S. military occupation of Iraq.

In a different war, in a different country half a century earlier, another scandal involving American military abuses of prisoners shocked the nation, prompted official investigations and courts-martial, and ended the careers of soldiers implicated in the case. In the matter of the U.S. Army’s 10th Reinforcement Depot in Lichfield, England, however, the abusers and the victims were all American soldiers.

More than 200,000 enlisted service members had passed through the depot in 1944, either en route to their first frontline assignments in World War II or as they were returning to the front after being wounded or reassigned. Soldiers ended up in the depot’s guardhouse for such minor offenses as being two hours late returning from a pass, and the guardhouse was run with the intent of making it “the most miserable place in the world.”

Troubling allegations surfaced in Stars and Stripes and U.S. newspapers that soldiers confined in the Lichfield depot’s guardhouse were subjected to terrible abuse at the hands of guards and depot officers. Former inmates said they were beaten with clubs, kicked, made to perform calisthenics or stand “nose and toes to the wall” until they were unable to do so any longer, and kept in solitary confinement in dark, cold cells. Men who complained about insufficient rations were made to eat massive portions of food and then administered castor oil to induce vomiting and diarrhea.

The army responded only after an outcry from the American people, who were shocked by stories of mistreatment of their men in uniform. Even then, the military authorities seemed more concerned with putting the matter to rest as quickly as possible than undertaking any real effort to investigate the allegations and punish the perpetrators of the abuses.

When the initial investigation substantiated the charges of brutality and inhumane treatment at the Lichfield depot, the army convened a general court-martial on December 1, 1945, to try the men accused of “cruel and inhuman disciplinary treatment of stockade prisoners” during the previous winter. But if military authorities hoped that such action would calm the critics, they were surely disappointed in the legal maelstrom that ensued. The courts-martial erupted into monthslong snarls of personality clashes, perjury and recantation of testimony, countering charges, and repeated attempts by the lead defendant to trigger a mistrial.

The first courts-martial focused on nine former staff members of the depot. All the defendants were enlisted men, a fact that was not lost on most observers, including a soldier familiar with the case who, in a letter published in Stars and Stripes, said they were “scapegoats.”

It appeared from the start of the trials that nothing would go smoothly. The defense’s primary strategy was obfuscation and denial, which the prosecution argued was not for the benefit of the defendants but to protect senior personnel who bore the real responsibility. “It was immediately apparent that the witnesses for the defense were falsifying their testimony and that such falsification was apparently prearranged and preconcerted,” the trial advocate wrote in his official report of the first trial. “To prevent an obvious fraud against the government of the United States it was necessary to break down this falsification. This resulted in an extended trial and with the now well-known results of defense witnesses, officer and enlisted, recanting their former false testimony.”

Witnesses for the prosecution testified that they had suffered brutal treatment in the guardhouse. Private Robert Schwerdtfeger said that on one occasion he had been beaten by six guards using clubs, rifle butts, and their fists before being confined in solitary for five days on bread and water with no light or heat, no blanket, and no cot. Sergeant Joseph Miller testified that when he was supervising work details at the guardhouse he had seen Lieutenant Leonard Ennis, one of the depot officers, following a prisoner who was being forced to double time around the compound, striking him in the back with a billy club whenever he slowed down.

Private James Jones, a former guard at the depot, testified that he had struck—and had seen other guards strike—prisoners and that repeat offenders were “worked over.” Prisoners testified that they were given only five to seven minutes to eat their meals, and those who complained were beaten by groups of guards. One soldier said he was beaten unconscious for refusing to eat a rotten potato. After regaining consciousness, he was put in solitary for 16 days and received only four loaves of bread for food.

Private Edward Skul testified that he was in the guardhouse on two separate occasions. On the second occasion, the group he arrived with was asked whether any of them had been there before; the seven or eight who answered in the affirmative were taken to the latrine one at a time and savagely beaten. Skul also said that he and some other prisoners were punished for complaining to an inspecting officer that they didn’t have enough time to eat. Skul and four others were forced to eat two trays of food each, then administered castor oil and made to stand against the wall while they were racked with vomiting and diarrhea.

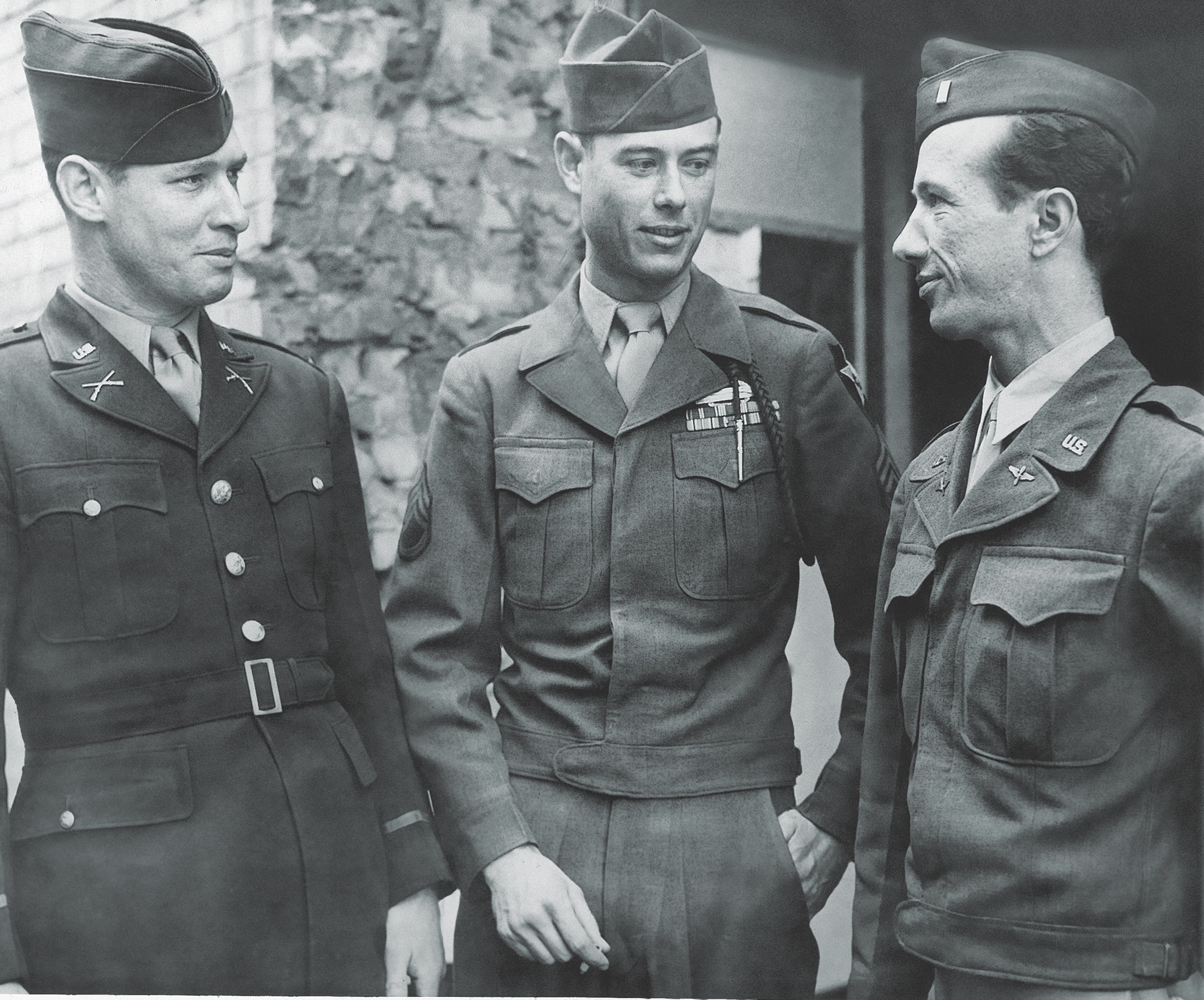

Sergeant Judson Smith, the former provost sergeant of the guardhouse, was found guilty as charged and sentenced to three years imprisonment at hard labor and a dishonorable discharge. The other enlisted defendants were given shorter sentences. The preponderance of evidence produced in these first trials finally forced the army to reluctantly turn its attention to the officers responsible for conditions at the depot. Its commander, Lieutenant Colonel James A. Kilian (who held the temporary rank of colonel); Major Richard LoBuono, the depot provost marshal; and Lieutenants Granville Cubage and Leonard Ennis were indicted. The first to be tried were the junior officers.

The defense produced numerous witnesses, mostly of officer rank, who testified that they never saw prisoners abused when they were at Lichfield. The depot chaplain dismissed the allegations of abuse out of hand, saying that prisoners were occasionally “shoved around” but insisting that “any man in the guardhouse will say he’s been mistreated.” The trial transcripts quickly filled up with ferocious arguments between members of the court as the legal proceedings careened ever closer to chaos. Some witnesses were rejected when it was shown that they were not at the depot during the period the investigation covered; other witnesses perjured themselves and then recanted; at one point the panel declared the defense counsel to be in contempt of court and then changed its mind; and the trial judge advocate, Captain Earl J. Carroll, made repeated official protests over what he described as attempts to intimidate or retaliate against enlisted soldiers who testified for the prosecution.

Carroll’s concerns were corroborated in April 1946, when seven enlisted men then in confinement on minor charges refused to testify at the court-martial of a former guard, Staff Sergeant James M. Jones. One of them, Private Otto Holt, told the court that he was being mistreated and feared further mistreatment if he testified.

It quickly became apparent that the problems at the depot went all the way to the top of the chain of command. In his trial, Cubage admitted falsifying his first testimony in the Smith case and said that Kilian had instructed him to do so. Defense counsel insisted that the accused officers were unaware of any mistreatment by depot staff, but the prosecution produced testimony refuting that. A former guard, Private William Morris, testified that Cubage once ordered him to beat a prisoner but then told him not to because the prisoner “was going to court the following morning” and the bruises would prove problematic.

When Ennis took the stand in his trial, he testified that Kilian had chewed him out for being too lenient and said: “What are you running down there, a playhouse or a guardhouse? You’ve got to be tougher.” Because of this order, Ennis said, he told the guards under his command that “if they were not rough enough they would be relieved from duty.” He admitted telling guards that “they could ‘drive a man to the floor’ ” but claimed he did not intend his words to be taken literally. The finger-pointing and blaming continued, with every defendant claiming that his superiors knew full well what was going on in the depot.

Cubage was found guilty, reprimanded, and fined $250. His punishment, coming on the heels of the harsher prison sentences and dishonorable discharges that the enlisted defendants had received, produced another round of outrage from both military and civilian observers. The Harvard Crimson summed up many opinions in an editorial that concluded, “The military caste system is merely adding cruel insult to a long list of injuries.” The assessment seemed borne out when Ennis, whom numerous witnesses said was particularly brutal in his treatment of prisoners, was also convicted but was only reprimanded and fined $350.

As the trials of the more senior officers got underway, the army found itself dealing with a public relations crisis that worsened with every official blunder and misstep. In February 1946, when the Senate Military Affairs Committee sent forward a list of 349 lieutenant colonels recommended for promotion to full colonel, Kilian’s name was on it. “An embarrassed committee,” newspapers gleefully reported, “asked the Senate if it could withdraw the list” when Kilian was indicted. The House Military Affairs Committee received so many letters protesting the results of the Lichfield trials that a form letter was prepared for committee members to reply to their angry constituents. “Please be assured,” the letter said, “that this inquiry will continue until the reduction to a minimum of injustices is accomplished.” This blithe assurance was repudiated when Kilian went to trial in the summer of 1946 in Bad Nauheim, Germany.

Kilian’s defense counsel maintained that the colonel knew nothing about any alleged mistreatment of prisoners. “There must have been something wrong at Lichfield which was concealed from me,” Kilian said when he took the stand. “It looks like they have passed the ball to the old man.” His junior officers, he insisted, had acted without his knowledge or instructions. The defense argued that he was only “following orders”—the same philosophy that the international war crimes tribunal rejected when it was offered in defense of senior Nazi officials during the Nuremburg trials that were even then in session 150 miles away.

When Cubage was recalled as a prosecution witness in Kilian’s court-martial, he testified that during the trials of the enlisted guards he had “attended meetings in Colonel Kilian’s room in London, at which meetings the testimony to be given in the Smith trial was discussed. At these meetings Colonel Kilian said he hoped to obtain a mistrial.” If Cubage’s testimony was true, Kilian’s actions presented a clear case of a defendant attempting to interfere with witnesses, and Cubage was not the only one to make that assertion. As the prosecutor told the court: “We have in this case a situation without parallel to my knowledge to any trial before a military court. We have a high ranking officer, a full colonel of the regular army, contacting witnesses, bringing them to his rooms, instructing those witnesses as to their testimony, checking up on what the witnesses have testified to, and calling them back for criticism when the testimony does not agree with some prearranged idea of his own. If this were an ordinary court of justice I would ask for a bench warrant and have him placed in arrest immediately.” The court chose not to pursue the matter of witness tampering.

Never one to avoid confrontation, Kilian took the stand in his own behalf. After four days of Kilian’s testimony, Carroll, the judge advocate, recommended that he should face additional charges of “contempt of court, interference with witnesses, and conspiracy to administer cruel and unusual punishments to prisoners in custody.” When the court rejected these charges, Carroll resigned in protest. Adding to the procedural chaos, Colonel Buhl Moore, the president of the court, effected his own resignation from the court-martial panel by asking that his fitness be challenged for cause. The reason, he said, was “friction between himself and law members of the court.”

When Kilian’s court-martial concluded on August 29, 1946, the outcome echoed the earlier trials of his subordinate officers. He was convicted of permitting conditions that resulted in the mistreatment and degradation of American soldiers, but the panel acquitted him of having knowingly permitted the abuses at the Lichfield depot. His sentence: an official reprimand and a $500 fine.

The verdict infuriated almost everyone except Kilian’s superiors. “This wrist-slap satisfied no one but the Army’s brass hats, who were only too glad to see the whole unsavory mess over and done with,” the correspondent for Time magazine wrote. The editor of the Washington Post had an especially pointed rebuke. “Generals Yamashita and Homma were convicted,” he wrote, referring to the two Japanese commanders who had been executed following U.S. Army courts-martial earlier that year. “Is the principle of a commander’s responsibility for Japanese only?”

One person who wrote a letter to Congress expressed the outrage that many Americans surely felt over “the obvious travesty [of] justice of the disparity in sentences between enlisted men and officers, particularly Colonel Kilian.” A former officer wrote, “Sadism, brutality, and flagrant misuse of authority and responsibility has gone virtually unpunished, with such punishments as has been made apparently being in inverse ratio to the rank and measure of control involved.” To critics such as these, it was especially galling that Kilian was promoted to the permanent rank of full colonel a few months after his court-martial conviction.

This stark imbalance between punishments was echoed 58 years later when soldiers accused of abusing Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib faced military justice. Two senior officers received reprimands and a brigadier general was demoted to colonel. Eleven enlisted soldiers, however, were court-martialed and received sentences ranging from terms of imprisonment, dishonorable or bad conduct discharges, fines, and reduction in rank. For many soldiers, it confirmed the rank-and-file’s long-held cynical belief that military justice is far from fair. “Different strokes for different folks,” the old barracks saying went, and the punishments handed down in two different cases in two different prisons half a century apart seemed to bear it out. MHQ

John A. Haymond is the author of Soldiers: A Global History of the Fighting Man, 1800–1945 (Stackpole Books, 2018) and The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law, and the Judgment of History (McFarland, 2016).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Laws of War | Disparate Justice

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!