As the light faded over Normandy, France, on June 7, 1944, Maj. John Donald “Don” Learment of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders was among many newly captured members of that Canadian infantry regiment bound for the German rear under guard.

“As we marched along,” Learment recalled, “I heard a shout from behind and turned to see a German lorry [troop truck] swerve into the marching column, pull out and continue on its way.” Two Canadian POWs were killed instantly; another was badly wounded. German troops in the trucks laughed and jeered as they sped off, obviously pleased with their handiwork. It was not an isolated atrocity. Other POWs reported scores of summary executions, after which the Germans either left the Canadians’ corpses to rot or dragged them into the road to be horribly mangled by passing vehicles.

Death and destruction were widespread in Normandy, but as many as 156 Canadians killed by the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) in the aftermath of the Allied invasion were not combat casualties—they were murder victims. Hailing from Nova Scotia’s isolated and impoverished mining and farming towns, the Canadians were killed while trying to surrender or executed well after their capture. The spate of murders committed by young fanatics of the Hitlerjugend constitutes one of the most savage war crimes committed during the Allied campaign in northwestern Europe.

On Aug. 19, 1942—less than two years before Allied forces stormed ashore in Normandy—German defenders decimated the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division as it mounted a massive raid on the occupied French port of Dieppe. Of the 6,086 men who made it ashore, 3,623 (nearly 60 percent) were killed, wounded or captured. Given that debacle, by midnight on June 6, 1944, Canadian commanders were relieved they had suffered “only” 1,074 casualties in return for significant initial gains.

At dawn on June 7, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division resumed its advance south from the Juno invasion beach, with the 7th Brigade on the right, the 8th in the middle and the 9th on the left. Opposing the Canadians were remnants of the German 716th Infantry Division and, just arriving on the field, the Hitlerjugend. The 7th Brigade faced little resistance and settled into defensive positions along the Caen-Bayeaux highway and a railway line that paralleled it.

On the far left of 9th Brigade, the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and Sherbrooke Fusiliers were about to enter combat for the first time. Advancing from Villons-les-Buisson through Buron and Authie, they were bound for the German-held airfield at Carpiquet, 5 miles south of their start line. Initial resistance was minimal, and both units made good progress. Shortly after noon the vanguard reported the airfield in sight. Despite optimism at brigade headquarters, however, the seeds of disaster had already been sown.

The 9th Brigade was on the extreme left of the Canadian advance, the British 185th Infantry Brigade advancing south from Sword Beach on its left flank. As the Canadians moved forward, however, the British got bogged down, leaving 9th Brigade with an exposed and vulnerable flank. Waiting to pounce were the 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, commanded by veteran Standartenführer Kurt “Panzer” Meyer, and 50 Panzer IV tanks from Obersturmbannführer Max Wünsche’s 12th SS Panzer Regiment. Both units were part of Meyer’s Hitlerjugend Division, among the most elite formations in the German military.

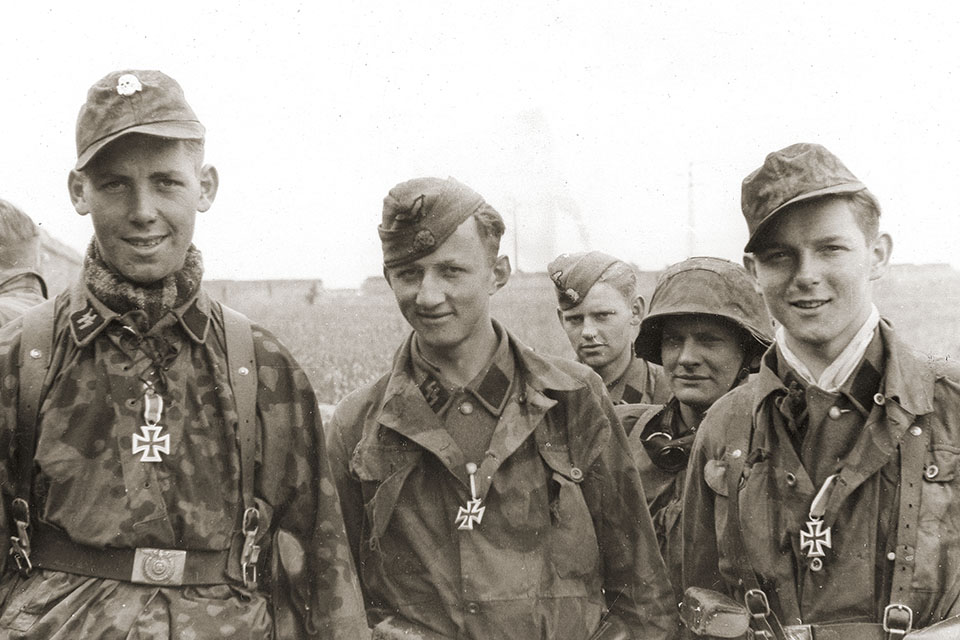

In early 1943, Adolf Hitler had approved formation of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. A cadre of veteran NCOs and officers drawn from the 1st SS Panzer Corps trained the division’s young grenadiers, all of whom were graduates of the Hitlerjugend organization. Most were under age 19 and had spent their entire lives in a Nazi milieu. Their education, their extracurricular lives, indeed their entire ethos was steeped in the warped values of National Socialism. With no alternative sources of information, saturated in a steady diet of propaganda about German “racial superiority” and wholly convinced of the righteousness of their cause, the young soldiers were willing to do anything for their Führer.

At a strength of almost 20,000 men, the Hitlerjugend was larger than other divisions of both the Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht. It was also better equipped, with more tanks than typical German armored divisions and such supplementary weapons as Nebelwerfer rocket launchers. Though unbloodied before D-Day, it had undergone better training than virtually any other combat formation in any World War II army. Training focused on teamwork and field craft, conducted under the eyes of harsh, battle-proven taskmasters who had spent years in the no-holds-barred slaughterhouse of the Eastern Front. Most exercises included the use of live ammunition, and while this led to an inordinate number of deaths, it also gave the young grenadiers valuable and highly realistic training.

In early April 1944, before the division moved from its training camp northeast of Antwerp, Belgium, into France in expectation of the Allied invasion, the Hitlerjugend reportedly received a series of secret orders. Assembled by platoon or company, with no officers present, the young grenadiers listened intently as senior NCOs verbally outlined the “attitude at the front” expected from the Hitlerjugend. They were expected to fight to the death and never surrender; French civilians were to be treated ruthlessly if they showed any signs of insubordination or insolence; and, most important in terms of this narrative, no prisoners were to be taken. Individual memories differ as to whether the directive ordered captured enemy troops to be shot out of hand or interrogated and then executed. But it is clear the rule of the day was that prisoners’ lives were without value.

Watching the Canadian advance from the vantage of Abbaye d’Ardenne, a medieval monastery northwest of Caen, Panzer Meyer quickly deployed his forces to prepare an ambush. Placing the majority of his armor directly in the 9th Brigade’s line of march, he arrayed the remainder of the tanks and his grenadiers on a reverse slope along the exposed Canadian left flank. Shortly after noon the 9th’s advance guard encountered Meyer’s blocking force, at which point the bulk of Meyer’s forces fell on the Highlanders’ exposed flank. In the ensuing melee the Germans overran the Canadian lead elements, taking many prisoners and driving the survivors back to their start line.

Learment, commander of the Canadian vanguard, was unnerved by his captors’ mania. “They were wildly excited and erratic…continually yelling and screeching to one another,” he recalled. “I actually thought they must have been taking drugs.” (In light of recent revelations about the prevalence of methamphetamine use in the wartime German military, the grenadiers may very well have been on drugs.)

The killing began immediately. A wounded Private Lorne Brown and Lance Cpl. Bill MacKay huddled in the same trench as the Germans overran the Canadian positions. MacKay, shot through the face and in his right arm, was fading in and out of consciousness when an SS trooper ordered the pair from their trench. Brown, who was bleeding profusely from his left wrist, was trying to rise to his feet when the trooper pinned him down with a boot and bayoneted him repeatedly in the chest and abdomen.

Constance Raymond Guilbert, a stonemason, was hiding in his basement when the fighting swept over his home in Authie. Crawling upstairs, he peered out a window in time to see a Canadian soldier, arms held high, in the act of surrendering. “He was crossing Madame Godet’s garden,” Guilbert recalled, “and when he had got within 3 or 4 meters of the Germans, he was shot down.”

As the Germans rounded up their captives, a trio of enemy troopers cut out eight Highlanders from Company C and ordered them to sit by the roadside. In this group were Cpl. Thomas Davidson and Pvts. John Murray, Anthony Julian and James Webster. After ordering the Canadians to remove their helmets, the three German guards summarily shot them. Not content with cold-blooded murder, the sadistic executioners then dragged Davidson’s body and that of another man into the street, where a passing tank soon ground their flesh and bones into unrecognizable gore. Six days passed before the Germans finally allowed the residents of Authie to bury the remains of all eight Canadians. “We were obliged to take two of them up with a shovel,” Guilbert recalled, “because they had been reduced to jelly.”

The Germans marched their surviving captives through Buron and Authie on the road to Caen. Any men unable to keep up were immediately shot. But stamina proved no guarantee. As the column marched through Authie, guards took a half-dozen able-bodied men aside and unceremoniously executed them. Another four, including a medic and his patient, faced similar fates before Major Léon M. Rhodenizer, commander of Highlander Company A, managed to convince the escorts to stop the killing. Regardless, German troops headed to the front left another nine dead by the side of the road.

When the POWs reached Meyer’s headquarters at Abbaye d’Ardenne, a group of German military police approached, asking for volunteers to step forward, though they refused to specify for what purpose. When none of the Canadians raised their hands, the Germans selected 10 at random and escorted them into the abbey. After a perfunctory interrogation, guards led each man in turn down a dark passageway into the abbey garden and murdered him. The first six were killed with blows from a cudgel. Their assassins soon tired of the effort, however, and simply shot the last four in the head. That night Meyer was heard to complain: “What do we want with these prisoners? They only eat our rations.” The German commander was implicitly condoning the murder of Canadian POWs under his very nose.

On the morning of June 8, German guards brought an additional seven Canadian prisoners to Meyer’s Abbaye d’Ardenne HQ. Jan Jesionek, a Czech conscript employed as a driver in the Hitlerjugend, was washing up in abbey that afternoon. He looked on as each man was called by name and escorted through an archway to the garden. As each prisoner entered, he was ordered to make a left turn, then promptly shot in the back of the head. A full 24 hours after the battle the Germans continued to slay their Canadian POWs.

In all, 58 Canadian prisoners were killed in the wake of the fighting around Buron and Authie on June 7. Eleven of the murders occurred in the immediate aftermath of the battle, 27 were committed in transit to the rear, and the last 20 were carried out with brutal precision far from the battlefield.

As the 9th Brigade’s nightmare unfolded, the 7th was preparing to defend against counterattacks. June 7 was relatively quiet, as their opponent, the 26th SS Panzer Grenadier Regiment, was only then arriving in the area behind Meyer’s troops. The 26th’s commander, Wilhelm Mohnke, had a reputation as a fearless warrior but a poor tactician. To his further detriment, while recovering from a severe leg wound suffered in 1941, he’d become addicted to morphine and was known to be highly erratic.

Befitting his reputation, Mohnke did not wait for his entire regiment to arrive in the area of operations before hurling his units piecemeal against the entrenched Canadians. At 3 a.m. on June 8 he directed probing attacks against the section of defensive line held by the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, threatening the entire position. Through the morning the fierce battle seesawed back and forth amid the stone villages and farmsteads on either side of the railroad embankment.

A German attack in the afternoon overran Companies A and C of the Winnipeg Rifles. Again the Germans took many prisoners, and again they began killing their captives in earnest. Lt. Don James was among a group of prisoners marched south down the road toward Le Mesnil-Patry. He watched as the SS guards separated out several men, ordered them to kneel on the roadside, then coolly shot them. It was overt act of murder, the unarmed POWs offering neither resistance nor provocation.

Another party of more than two-dozen Canadian prisoners was marched to the headquarters of the 12th SS Reconnaissance Battalion at Château d’Audrieu. There in the shade of a sycamore tree behind the château Sturmbannführer Gerhard Bremer interrogated Maj. Fred Hodge, Lance Cpl. Austin Fuller and Pvt. Frederick Smith. Infuriated by their refusal to divulge any more than name, rank and serial number, Bremer abruptly ordered them shot. Minutes later the same fate befell Pvts. David Gold, James McIntosh and William Thomas.

That afternoon another seven prisoners were marched into the woods and shot in the face, chest and head. Just after 4:30 p.m., as French civilians Leon Leseigneur and Eugene Buchart passed the château, they watched as German guards herded the 13 remaining POWs into an orchard. As the Frenchmen strode out of view, they heard a fusillade of shots as the Germans executed the Canadians. According to forensic evidence recovered from the scene, an officer had checked each body for signs of life and dispatched any survivors with a shot to the head.

Perhaps alone among the officers of the Hitlerjugend, Sturmbannführer Bernhard Siebken—commander of the 26th SS Panzer Grenadier’s 2nd Battalion—insisted on treating captured Canadians with strict adherence to international standards. On the evening of June 8, despite Mohnke’s insistence he stop sending prisoners to the rear—a demand Siebken correctly inferred as an order to execute them—he dispatched a group of 40 Canadian POWs from a barn in Moulin toward Mohnke’s HQ at Le Haut-du-Bosq. Little more than a mile shy of the village an approaching German staff car screeched to a halt, and an agitated SS officer stepped out, alternately threatening and shouting orders at the NCO leading the column. Moments later their guards marched the hapless Canadians into an adjacent field and seated them in rows. Grenadiers from a waiting half-track then promptly dismounted and sprayed the men with 9mm rounds from their MP 40 submachine guns. Miraculously, five survived the fusillade, were able to escape, and later testified to the massacre.

The final act in this macabre circus occurred on June 17 back at the Abbaye d’Ardenne. Captured in battle early that morning and sent to the abbey for interrogation, Lt. Fred Williams and Lance Cpl. George Gerald Pollard of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders were killed on the orders of either Meyer or Obersturmbannführer Karl-Heinz Milius, Meyer’s successor as commander of the 25th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

Within two weeks of the D-Day landings elements of the Hitlerjugend Division had murdered nearly 160 Canadians. Most of the men, unarmed and ostensibly POWs, had faced humiliating executions far from the field of battle. Yet despite the heinous nature and obscene number of these atrocities, the perpetrators largely escaped justice.

Though at his postwar trial Meyer was not personally charged with any of the killings, he was judged to have fostered an ethos that approved of, even encouraged, the murder of prisoners. In this sense he was deemed “vicariously responsible” for the Canadians’ deaths. Found guilty, he was sentenced to death. The decision was subject to review by Maj. Gen. Christopher Vokes, the court’s convening authority and General Officer Commanding the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Europe. Vokes, reluctant to hold field commanders responsible for acts carried out by subordinates, commuted Meyer’s sentence to life in prison. The former SS officer was sent to Canada in April 1946 and served five years in New Brunswick’s Dorchester Penitentiary. He was transferred to a British military prison in Werl, West Germany, in 1951 and released on Sept. 7, 1954. He died of a heart attack on Dec. 23, 1961, his 51st birthday.

Mohnke remained loyal to Hitler through the final Battle of Berlin and surrendered to Russian troops during the conflict’s closing hours. On May 9, 1945, the Soviet secret police flew him to Moscow for interrogation. He spent the next six years in solitary confinement in the bowels of the notorious Lubyanka Building before being transferred to the officers’ prison camp in Voikovo. Mohnke remained in Soviet captivity until Oct. 10, 1955. After a quiet postwar career as an auto dealer, he died in Germany on Aug. 6, 2001, at age 90.

In August 1944 British troops captured Wünsche, who sat out the rest of the war in a prison camp for high-ranking German officers in Caithness, Scotland. In 1948 Allied authorities, their appetite for war crimes trials seemingly sated, released Wünsche and returned him to Germany. He managed an industrial plant in Wuppertal and retired in 1980. On April 17, 1995, a few days shy of his 81st birthday, Wünsche died peacefully in Munich.

Bob Gordon is a Canada-based historian whose work has appeared in newspapers and magazines in that nation, the United Kingdom and the United States. For further reading he recommends Conduct Unbecoming, by Howard Margolian; Meeting of Generals, by Tony Foster; and Kurt Meyer on Trial: A Documentary Record, edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Chris M.V. Madsen.