The venerable, award–winning series American Experience has often featured engaging stories about the American West. Several of the episodes of the Native American series We Shall Remain and the insightful biography Wyatt Earp stand as recent examples. The series has at times dealt with “Old West” stories that involved range wars or conflicting claims to the discovery and ownership of natural resources. On Monday, January 17, 9:00 pm ET on PBS, American Experience will premiere another of these adventure-filled discovery sagas. But rather than a battle over gold or silver or water rights, this program tells the little-known story of a battle over … bones.

Really, really old bones.

Specifically, American Experience: Dinosaur Wars tells of a battle that ranged over many thousand square miles and lasted for decades over the bones of prehistoric animals and dinosaurs that once thrived in what is now the western United States. The combatants in this fight for fossils were just two men: pioneering paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

“It really is an American Western story,” notes the program’s writer-producer-director Mark Davis. “And in some ways, even though they didn’t shoot at each other, they behaved as though they were in a range war.”

This range war started because the scientific world was beginning to embrace the theory of evolution that resulted from the publication of British scientist Charles Darwin’s landmark work on his study of the natural world.

“The timing was really remarkable,” says Davis. “Darwin published (On the) Origin of Species in 1859. The one thing he lacked to back up his theory was fossil evidence of animal species in transition from one form to another. Less than 10 years later, the transcontinental railroad opened the west to scientists for the first time, and the fossils were there for the taking. Just at the moment when science was asking the question ‘How did life evolve, what are the details of the story?’ bones became available, and Cope and Marsh were really the first two American scientists to go west and exploit it.”

“The timing was really remarkable,” says Davis. “Darwin published (On the) Origin of Species in 1859. The one thing he lacked to back up his theory was fossil evidence of animal species in transition from one form to another. Less than 10 years later, the transcontinental railroad opened the west to scientists for the first time, and the fossils were there for the taking. Just at the moment when science was asking the question ‘How did life evolve, what are the details of the story?’ bones became available, and Cope and Marsh were really the first two American scientists to go west and exploit it.”

To say the two men’s backgrounds and personalities were diverse would be understatement. Marsh, a conniver and a loner, often treated the teams who worked with him contemptuously, and he didn’t want to share credit. Cope was loved by his friends and co-workers, and he gave credit to others’ contributions—but he also could be quite defensive about his work, a quality Marsh would later exploit. Cope had a family of his own while Marsh never married or had a romantic relationship.

Both men had money behind them for their work. Cope came from a wealthy Quaker family in Philadelphia. Marsh was raised on a struggling farm in upstate New York, but he was bankrolled by his uncle, philanthropist George Peabody, who plucked him off the farm, educated him and installed him into a Yale professorship. Both paleontologists were also keenly ambitious and truly interested in making scientific firsts as their careers got started in the late 1860s. They actually became fast friends for a time while studying in Berlin early in their careers.

Cope worked, studied and produced a great number of scientific papers at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, of which he was a member. The Philadelphia Academy was the oldest of America’s scientific enclaves, where the leisurely exchange of information was the realm of American science at the time. It also had the world’s first displayed dinosaur fossil, called Hadrosaurus, a skeletal set of bones discovered in a Haddonfield, New Jersey, quarry. The trouble between Cope and Marsh began over the source of the Academy’s prehistoric vertebrate.

“Before the Civil War, American science was a gentleman’s pastime, done by amateurs,” Davis explains. “That’s the world Cope came from, a kind of heir to the tradition of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson. Marsh was something new in the world of American science—a professional from a humble background. He operated aggressively, like a businessman. He didn’t follow the rules of the older gentleman’s world.”

After Cope introduced his friend to the Haddonfield find, Marsh infuriated him by making a secret deal with the quarry’s owner to get all future fossils from the pit, effectively poaching on what Cope considered his primary source. Making use of his opportunistic character, along with the money and prestige that came from his position as a Yale scientific scholar, Marsh became the type of enterprising scientist that had been leading Europeans to make the world’s scientific advances.

After Cope introduced his friend to the Haddonfield find, Marsh infuriated him by making a secret deal with the quarry’s owner to get all future fossils from the pit, effectively poaching on what Cope considered his primary source. Making use of his opportunistic character, along with the money and prestige that came from his position as a Yale scientific scholar, Marsh became the type of enterprising scientist that had been leading Europeans to make the world’s scientific advances.

Unlike the Europeans, he had the advantage of living in the United States where the topography was more conducive to fieldwork than were the large forests and damp conditions of Europe. America’s westward-expanding railroads opened the areas where vast dinosaur fossil deposits lay awaiting discovery.

After returning from Europe, Cope traveled west and south from Philadelphia in his natural studies, but Marsh was the first to see the potential for large fossil finds in the geological formations of the American West when in 1868 he first went on a sightseeing rail tour of the frontier.

Marsh returned with his eyes opened to the West’s possibilities, and he went straight to work assembling the necessary men and equipment for a return trip. Eventually, his search for bones would lead him to the upper prairies of Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

Marsh returned with his eyes opened to the West’s possibilities, and he went straight to work assembling the necessary men and equipment for a return trip. Eventually, his search for bones would lead him to the upper prairies of Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

Cope followed, organizing his own expeditions, which became more frequent once he received a large inheritance. Marsh operated in a clandestine manner, even employing spies to watch Cope, trying to shut him out from new finds. But Cope continued to explore, even entering the badlands of southeastern Montana alone—and, being a Quaker, unarmed—just weeks after George Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn. All the while the two continued a war of words in scientific journals, each attempting to discredit the other. Rather than blazing six-guns, the weapons of their “range war” included forged documents, spies, and battles over who could mine which fields of bones.

“Cope was trying to keep up,” says Davis. “He really didn’t have the resources or the institution behind him that Marsh had, but he had just relentless energy. Cope was a brilliant, prolific scientist who worked all over the ‘tree of life,’ rambled all over the West, and could see the broad sweep of evolution. But he was terrible at politics. Marsh was well connected, a great politician, a well-financed institution builder. But compared to Cope, he was a plodder intellectually. Each had something that the other lacked and badly wanted and I think it (the competition) was driven a lot by jealousy.”

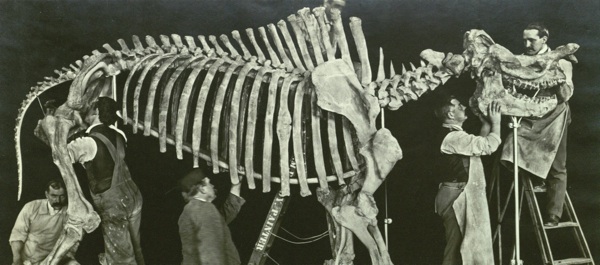

Both men made significant contributions to the field. Marsh presented bones to trace the evolution of the horse and received praise from Darwin himself. Cope was, at the time, the most prolific author of scientific papers in American history. Together they advanced America’s stature in the global scientific community and introduced the world to evidence of the largest creatures on earth—the skeletal remains of the late Jurassic dinosaurs found at Como Bluff, Wyoming.

Mark Davis brings a lot of experience to the program. He started making films about dinosaurs and evolution for NOVA in the 1980s. The on-camera experts, paleontologists and historians, bring some plain-talking insight into an arena that could quickly turn into a yawn-fest of scientific names and theories. And Robert Bakker, who is a noted dinosaur paleontologist, has the look of a prospector who just came in from a long day toiling on his claim. In this case, that claim would be the wonderful world of dinosaur bone sites originally mined by Cope and Marsh. Several of these places are shown in beautiful panoramic vistas in the program, and some are now preserved in public parks such as Dinosaur National Monument in Utah and Colorado.

Mark Davis brings a lot of experience to the program. He started making films about dinosaurs and evolution for NOVA in the 1980s. The on-camera experts, paleontologists and historians, bring some plain-talking insight into an arena that could quickly turn into a yawn-fest of scientific names and theories. And Robert Bakker, who is a noted dinosaur paleontologist, has the look of a prospector who just came in from a long day toiling on his claim. In this case, that claim would be the wonderful world of dinosaur bone sites originally mined by Cope and Marsh. Several of these places are shown in beautiful panoramic vistas in the program, and some are now preserved in public parks such as Dinosaur National Monument in Utah and Colorado.

The bulk of the visual material in the program consists of still images and photographs, but many are unusual and an almost-constantly moving camera keeps them interesting. There are also dinosaur bones as now assembled in museums around the country—the fruit of the labors of Cope and Marsh, who died relatively young without seeing what their “dinosaur war” would lead to. Other than discussing the role played by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as the federal government entered the paleontologists’ war in the last decade of the 19th century, the program does not expand on how the American public reacted to all this. According to Davis, the ideological differences over what these discoveries meant to the story of creation would not surface until this science began to be taught in schools in the 1920s. That aside, Dinosaur Wars makes a very effective presentation of what would be one of the last, and most unusual, struggles in American Western lore.

(Editor’s note: As stated, the ideological battle over evolution began in earnest in the 1920s. However, in 1797, Vice-President Thomas Jefferson was ridiculed and accused of atheism for a paper he wrote and presented to the Philosophical Society in Philadelphia about fossil bones sent to him from what is now southeastern West Virginia. See “Thomas Jefferson and American Vertebrate Paleontology.”)