A common maxim during the Civil War held that it was “a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” Both Union and Confederate critics leveled this charge—especially in the wake of conscription. But was that the case? Did the poorer classes of Union and the Confederacy bear the burden of fighting while the rich remained at home? The answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no.

In the two principal armies in the Eastern Theater, the Union’s Army of the Potomac and Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia, precise numbers are difficult to determine. Approximately 240,000 soldiers served in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (although the average at any given time ranged between 35,000 and 90,000).

On the Union side, approximately 350,000–375,000 men served in the Army of the Potomac (although its strength at any given time averaged 125,000). Most of the soldiers on both sides were in their teens or early twenties when the war began. Single men—those with the fewest ties to keep them at home—were the most likely to rush off to war in 1861.

Unwedded men, therefore, dominated both armies. The same held true for soldiers with children. Only one in three Confederates had children at home. But Union soldiers were even less likely to be married and have children than Confederates—only one of five Army of the Potomac soldiers left a family behind. Ninety-five percent of Lee’s soldiers came from farming communities. Conversely, only 30 percent of soldiers in the Army of the Potomac were farmers or farmhands. The Army of the Potomac was instead a predominately working-class army. The largest segment were day laborers, finding any work they could. Others constructed homes and buildings, some worked as shoe or boot makers, while a handful held skilled positions such as blacksmiths.

The next question concerns personal wealth. It is helpful to consider not an individual soldier’s wealth, but rather that of his family, as a majority of the soldiers on both sides still resided with their parents or older siblings. Approximately half of Lee’s men still lived with their families and therefore reaped the benefits of their parents’ lifestyle and wealth. For example, in 1860, Howlit Irvin was a student and owned nothing. But his father was the former lieutenant governor of Georgia, whose wealth was valued at $170,000—including an estate with 117 slaves—making him one of the richest men in Georgia, if not the South.

On the Union side, two of five soldiers still resided with their parents or other family members when the war began. Examining the combined personal and family wealth therefore reveals a dramatic disparity between Union and Confederate soldiers: The median wealth of most Federal soldiers was a paltry $200. Conversely, soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia enjoyed a median personal and family wealth that was 6½ times greater than their Union counterparts.

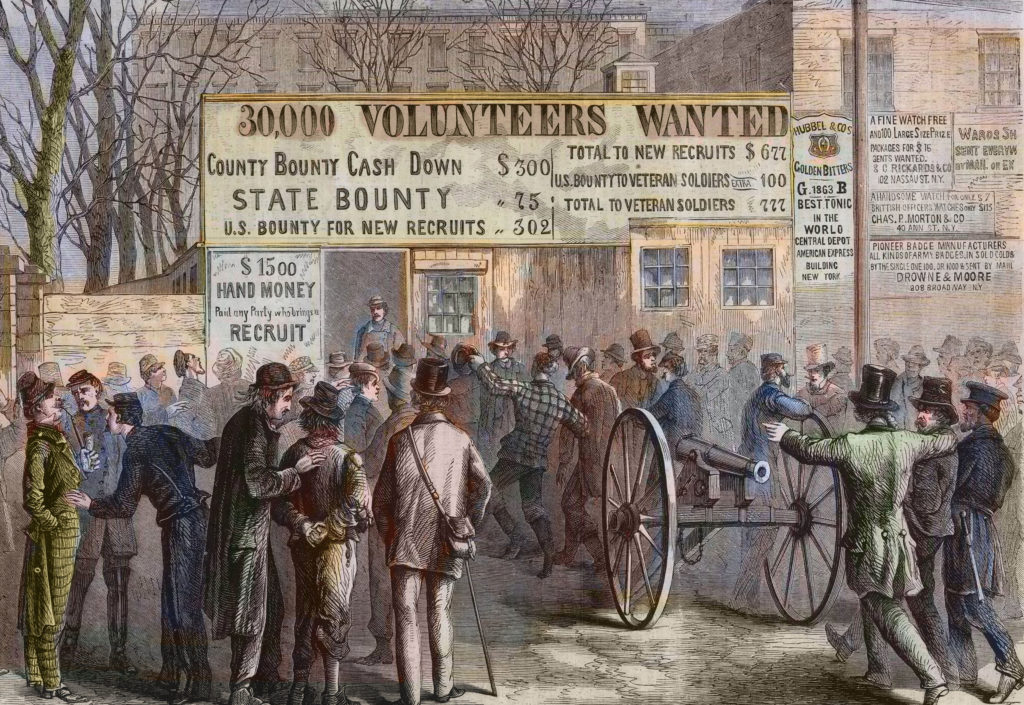

Moreover, more than half of the Union soldiers fell into the category of “poor.” In fact, historian William Marvel has shown that the men who enlisted earliest in the Union Army proved to be some of the poorest. While popular belief has held that those who enlisted earliest did so from unbridled patriotism, Marvel finds that the desire for economic relief proved a more likely motivating factor for Union soldiers in 1861-62.

Many men still reeling from the effects of the financial panic that swept New York City in 1857 found the prospect of a steady paycheck and bounties their overriding motive for enlisting. For example, when men from the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Infantry were captured by Confederates at Ball’s Bluff in the fall of 1861, they explained their motivations: “A great many of them gave it as their excuse for fighting that they were out of employment and had nothing else to do,” noted their North Carolinian captor.

Returning to the Army of Northern Virginia, perhaps even more telling when we consider the lament of a “poor man’s war” is that Lee’s army had, as a percentage, according to historian Joseph Glatthaar, fewer poor folks (those worth less than $800) and more wealthy men (those from families claiming more than $4,000 in property) than the Southern states at large.

There was considerable affluence among Lee’s army, and that wealth was tied to the ownership of enslaved people. As Glatthaar has explained, “slaveholding had a powerful grip on…Lee’s army.” While only 13 percent of Lee’s soldiers were slaveholders, if we look at their families—we find that 44 percent came from slaveholding households—a statistic revealing that slaveholders were far more prevalent in Lee’s army than in the Southern population at large (where only 25 percent of households owned slaves).

In the Confederacy, therefore, this was not a poor man’s fight. Slaveholders, among the richest in the South, served in disproportionally high numbers in Lee’s army. Believing that slavery was under attack, they flocked to the cause. Those from the middle- and upper-classes in the Army of the Potomac, however, did not have the same financial interest in fighting. Even those who came from the wealthy class would not have lost a fortune had the South achieved its independence.

But that fact must be balanced with the reality that there were certainly those from more privileged backgrounds that fought for the Union. For example, approximately 1,300 men with Harvard ties fought in the Union ranks—they clearly were from the privileged class. In other words, the poor, elite, and middle classes were represented in the Union Army just as they were in the Confederate armies.

Confederate Conscription

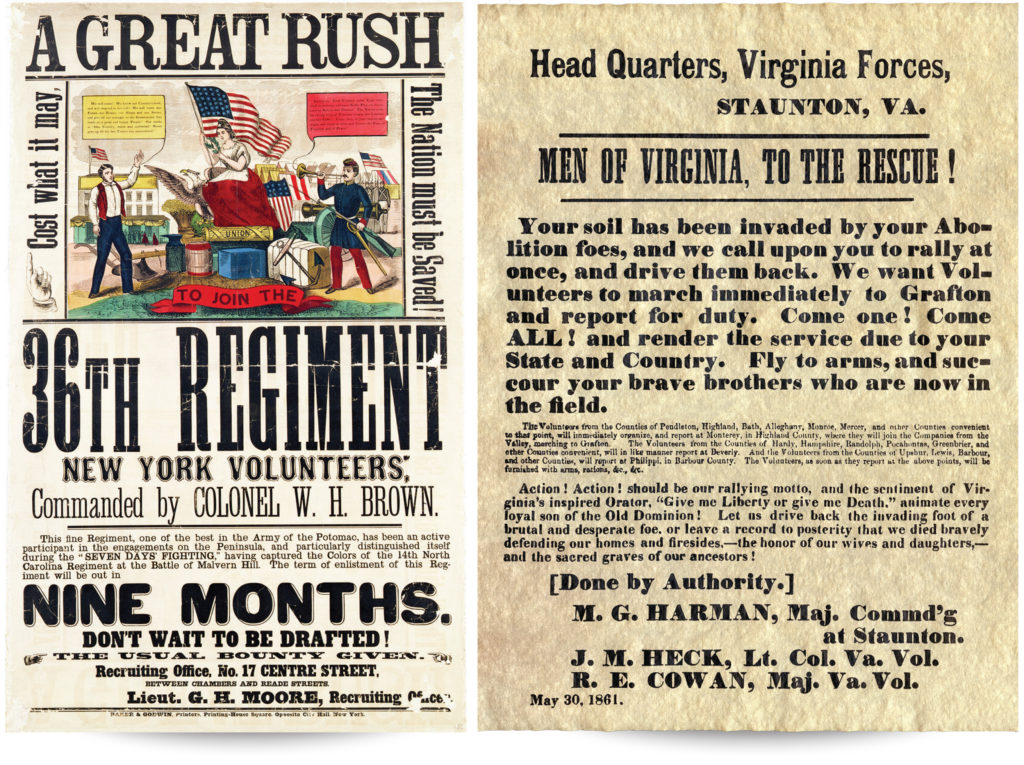

Despite these men’s service, by the spring of 1862, Confederate armies were shrinking because of battlefield casualties, sickness, and disease, but also as a result of expired enlistments and desertion. The Confederate Congressresponded to the emergency by taking one of the most momentous steps of the war: conscription (or the draft). On April 16, 1862, the first of three Confederate conscription acts became law and required the following:

- All able-bodied White men already serving would have their enlistments extended for two years—men who had enlisted in good faith for one year’s service

- All other White males between the ages of 18-35 would serve for three years

Two subsequent revisions to the legislation, passed in September 1862 and February 1864, changed the age limits—eventually setting the range from 17-50. In effect, if the Confederacy got a man into uniform, he never got out. The draft was unprecedented in American history. But we need to keep in mind it was as much carrot as it was stick. The potential for conscription convinced men to enlist. Men of 1861 worried that if they didn’t reenlist, they would be forced to add three years, instead of two. Others worried that if they went home and risked draft, then they would be forced to serve in units other than the ones they had joined by choice. Fear of serving with strangers drove Spencer Barnes of North Carolina to admit to his father, “I hate to be thrown into another company.”

There certainly were those that complained. Unionists were distraught at having to fight for a cause they opposed. Others complained on ideological grounds: they argued that the Confederacy had been founded to protect states’ rights—but the conscription law allowed the central government to usurp states’ rights. Then there was the list of exemptions from the draft. The occupations exempted included government officials, teachers, millers, some artisans, and laborers engaged in industries such as mining, railroads, textile mills—all things necessary for the war effort. But there were two exemptions that particularly galled many Rebels. The first was the Overseer Clause—added in October 1862. This clause exempted one white male from each plantation with 20-plus slaves under the assumption that one white man was needed to manage large numbers of slaves. But non-planters and slave-less whites claimed the clause gave preferential treatment to planters and their sons.

The second exemption that triggered protests was substitution, which allowed draftees to avoid military service by finding someone exempt from the draft to replace him—this meant hiring someone who was either under or over the mandatory conscription age, someone whose trade of profession exempted him, or a foreign national. Prices for substitutes in the South were said to range as high as $3,000 in specie (gold) or even higher in Confederate money—a sum that only the very wealthy could afford. Like the Overseer Clause, this provision also seemed to favor the wealthy and provoked calls of “rich man’s war,” and the Confederate Congress did ultimately abolish the practice.

But did conscripts change the composition of Lee’s army? In large part, no, because nearly all of those men volunteered. Only eight percent were drafted or served as substitutes. In fact, the vast majority of Lee’s soldiers, nearly 80 percent, volunteered before the Confederacy implemented conscription. But draftees did tend to be poorer and owned fewer slaves than their comrades who volunteered. They also tended to be older—between the ages of 26 and 40. The most glaring difference between Confederate volunteers and draftees, however, revolved around marital status and children: 70 percent of conscripts were married. And nearly every drafted married soldier left behind children. In other words, having a family and children to support made men less likely to volunteer than the younger, single enlistees.

The Union Draft

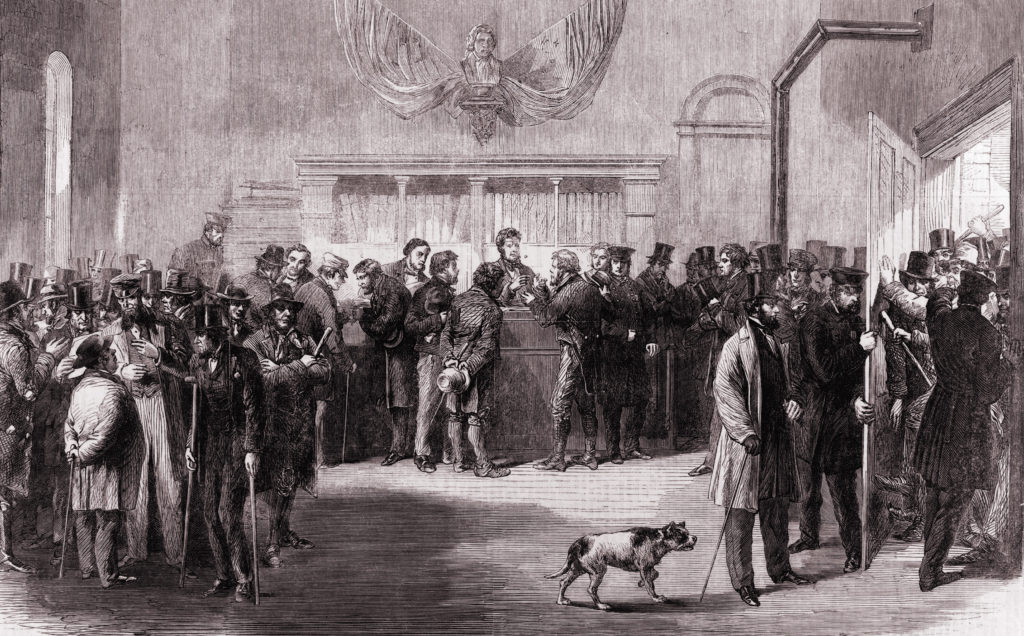

The Union draft began a year after Confederate conscription and operated somewhat differently. Each loyal state was divided into recruiting districts, and each district had a quota to meet based on population. When the recruiting district failed to meet its quota through volunteers, soldiers would be drafted by lottery among men between the ages of 20 and 45—as well as immigrants seeking U.S. citizenship. If a man’s name was selected by the lottery—he had three options: enlist, find (and pay) a substitute to take his place, or pay a $300 commutation fee that exempted him from that round of the draft. In 1860, $300 would have been the equivalent of the annual wage of an unskilled laborer.

Unlike Confederates, the Union lawmakers allowed no occupational exemptions. But there were some exemptions—exemptions that critics charged favored the poor. For example, the only son of a widow or of infirm parents did not have to serve if he was their primary support. And a widower with children younger than 12 was not subject to conscription. Those with more means, of course, could afford to hire a substitute (essentially bribing someone else to fight for them) or pay the commutation fee. Thousands of middle and upper-class Northerners, including John D. Rockefeller and future president Grover Cleveland escaped military service by these means.

In the first national draft levy, in 1863, only one drafted man out of every 30 went to war. In some states, this number was far higher—for example, in Connecticut only one in 63 drafted men found himself in a blue uniform. In some communities, men subject to the draft pooled their money in draft insurance clubs that would hire substitutes for those selected. As Marvel pointed out, “[U]nless a man was unable to simultaneously support his family and hire a substitute or pay the commutation fee, it was easy to avoid going into the Union Army, and the overwhelming majority of those who were called to serve” avoided it. In 1864, Congress abolished the commutation provision, but not substitution.

As it had in the Confederacy, the Northern draft provoked outrage, with many arguing that it abridged their fundamental personal liberties. Both substitution and commutation produced cries of “a rich man’s war” just as the Overseer Clause had done in the South. Combined with emancipation, the draft of 1863 unleashed a storm of violent protests in the loyal North. Some provost marshals—those in the army charged with enforcing of the law—were shot, their families threatened, their property vandalized. More than 160,000 men—one-fifth of those drafted—refused to report for duty. Thousands more who did eventually deserted and others dodged the draft by going to Canada.

The draft likewise spurred protests. Democrat politicians, especially Copperheads (the name given to anti-war Democrats), inspired the most violent protests. The most notorious and deadliest rioting erupted in New York City on July 13-17, 1863. Anti-conscription sentiment spilled into four of the bloodiest days of mob violence in the city’s history—by the time the smoke cleared, at least 105 people, mostly rioters—lay dead and another 300 were severely injured. Twenty thousand armed troops marched from Gettysburg to quell the rioting.

The draft began without incident on July 11—but that evening and into the next day disgruntled draftees, including urban laborers and immigrants—many of whom were Irish—gathered and planned to disrupt the draft proceedings by attacking the provost marshal’s station and setting it on fire. The cry of a “rich man’s war” may have ignited the riot, but racial tensions and economic dislocation fanned the flames. The working poor, including the mostly unskilled Irish workers, competed with African Americans for jobs—yet African Americans were not subject to the draft. This infuriated Whites—they might be forced to serve and die in a war that was now about liberating slaves. Rioters burned the Colored Orphan Asylum and rampaged through Black neighborhoods lynching at least six African Americans on lampposts and brutally mutilating others. There were other smaller riots—in Boston, in New Hampshire, and even Wisconsin—but theses riots served as the high point of draft resistance.

The question remains: did the draft alter the composition of the Union Army? Historians have yet to answer this question regarding the Army of the Potomac as fully as they have for the Army of Northern Virginia.

What we do know is that in the Army of the Potomac, approximately three percent were drafted while another six percent were substitutes. Like the Confederate draft, the Union draft was far more crucial as a spur to local recruitment than as an end unto itself. And, as such, it likely had a similar impact—that is, draftees were probably poorer, older, and more likely to be husbands and fathers than their volunteer counterparts.

So was the Civil War a poor man’s fight?

In answering this question, we need to keep in mind the difference between reality and perception. Many people at the time believed that it was a rich man’s war and poor man’s fight. But a closer examination suggests that all classes were well represented. Indeed, as Glatthaar has explained, “on the whole, soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia were very comfortable financially, whereas the men in the Army of the Potomac were comparatively poor.”

Even though Lee’s soldiers were more likely to come from wealthy families, we should keep in mind that war placed great strain on the poor and middle classes of both sides. War always takes harder toll on those who have fewer resources. Even those of the middle class had a great deal to lose in the war. Their families had worked quite hard to achieve even moderate success—and they worried about losing all of it. Given the scale of the mobilization on each side—the war did not belong to one class alone.

Despite what some chose to believe, it was not a poor or rich man’s fight, it was every man’s fight.

Caroline E. Janney is the John L. Nau III Professor in History of American Civil War and Director of the John L. Nau Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia. She has published seven books, including Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox (2021) winner of the 2022 Lincoln Prize.

This article is an excerpt from The Great Courses’ 10 Big Questions of the American Civil War, by Caroline E. Janney on Audible.com. Janney’s lecture is based on research from Joseph Glatthaar’s books General Lee’s Army and Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia, and his article, “A Tale of Two Armies,” published in the Journal of the Civil War Era, Vol. 6, No. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 315-346. William Marvel’s book, Lincoln’s Mercenaries, also provided a wealth of important data.