After sundown, the Luftwaffe’s leading night fighter wreaked havoc on RAF bomber formations.

Germans took an enormous toll on the RAF’s Bomber Command during World War II. Among the most aggressive Nachtjäger, or night fighters, were Helmut Woltersdorf (24 victories), Martin Drewes (43), Ludwig Becker (44), Heinrich Prinz zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (88) and Helmut Lent (110). Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer, however, topped them all, downing an incredible 121 Allied aircraft to become history’s night-fighting ace of aces.

Born in Stuttgart on February 16, 1922, Schnaufer was exposed during his teens to the rapidly expanding nationalism of the Third Reich. Intrigued by the state-sponsored propaganda on aviation, he entered glider school in Potsdam in 1939 and joined the Luftwaffe on November 15 of that year. Originally trained on multi-engine aircraft and the Messerschmitt Me-110 Zerstörer (destroyer) twin, he switched to night fighter training and was assigned to II Gruppe of Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (II/NJG.1) in November 1941, and became its technical officer in April 1942.

The Luftwaffe’s principal aircraft for night interception, the Me-110 was armed with two 20mm cannons and four 7.92mm machine guns in the nose, in addition to a flexible rear-mounted machine gun. The Germans discovered the most successful method of attacking enemy bombers was to approach from below and behind, using the dark land as cover and the lighter night sky to silhouette a victim. Once in position, the pilot would pull up and fire, trying to hit the inboard fuel tanks in the wings. Since the tanks were not self-sealing, a few well-placed shots usually resulted in the bomber’s catching fire or exploding.

In late 1943 Paul Mahle, a Luftwaffe NCO, came up with the idea of using a pair of 20mm cannons mounted obliquely behind the pilot. After numerous tests of the system, code-named Schräge Musik (slanted music), it was installed on the Me-110G. Nachtjäger pilots now had a choice: Attack in the usual way or position their fighters some distance below a bomber, then gradually climb to the bomber’s underside and fire the dorsal cannon at a 70-degree angle from about 100 to 200 meters away. Schnaufer wrote that he generally aimed at the right-hand wing, a large target. But unlike some who became addicted to the Schräge Musik method, he was equally proficient with both tactics.

The Me-110G night fighter normally carried a three-man crew. Wilhelm Gansler was Schnaufer’s usual flight mechanic, while radio operator Fritz Rumpelhardt was responsible for communications, navigation and defending their tail with the 7.92mm MG 15 machine gun. Later Me-110G variants were equipped with twin machine guns, but Schnaufer eventually dispensed with his rear armament entirely to increase his plane’s speed. Although both men contributed to Schnaufer’s 121 victories, Rumpelhardt officially shared in 100 of them.

Schnaufer scored his first kill on the night of June 1-2, 1942, when he shot down a Handley Page Halifax of No. 76 Squadron, RAF, about 15 kilometers south of Louvain, Belgium. Schnaufer positioned his Me-110 slightly below the Halifax and about 150 meters to the side, and his victim was apparently caught completely off guard when Schnaufer went in for the kill, pulling up and banking in astern of the British bomber. He pressed the firing button, and the Halifax flew through a deadly concentration of cannon shells and machine gun bullets. At the last moment Schnaufer shoved his control column forward, diving steeply away to avoid any return fire from the Halifax’s rear turret before making another pass at the bomber. His first pass started a fire, but with the second attack flames began pouring out of the wing, sealing the bomber’s fate. Just before the Halifax dived to earth, all but two of the crewmen managed to bail out. “We saw the crew bailing out,” Schnaufer later wrote. “We were glad that they would survive and become prisoners. Our joy at our first victory was boundless.”

Schnaufer’s elation was short-lived. As he closed in on a second bomber, its return fire struck him in the left leg. Although he landed safely at Saint-Trond airfield, he did not return to II/NJG.1 until June 25. It would be the only time that Schnaufer or any of his crewmen were wounded during the war. On August 1, he came back into his stride and then some, downing two Vickers Wellingtons and an Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley. His score stood at seven at the end of the year, and he steadily raised it to 42 by the end of 1943, when he received the Knight’s Cross.

On October 16, 1944, Adolf Hitler added the Diamonds award to Schnaufer’s Knight’s Cross. He was placed in command of NJG.4 at Gutersloh on November 4, and promoted to major in December. At 22, he was the Luftwaffe’s youngest wing commander. His score stood at 108 as 1945 began, but he was far from finished.

Schnaufer’s most productive night came on February 21, 1945, when he was credited with destroying nine RAF heavy bombers—two that morning and seven more that evening. Research shows that he actually destroyed 10 aircraft on February 21, one of which was not officially acknowledged.

His eighth victim that night was an Avro Lancaster with No. 463 (Australian) Squadron returning from a raid on the Mittelland Canal. Commanded by Flying Officer Graham Farrow from South Australia, the Lancaster had a big problem: a hung-up 1,000-pound bomb. Farrow was flying level with the bomb bay doors open while a crewman tried to resolve the situation. Shortly after the bomb was finally jettisoned, the Lancaster was hit with cannon shells, damaging the far right engine and shattering the navigator’s table, electrical panel and starboard wing flaps. The flight engineer was wounded by shrapnel. Although none of the crewmen could positively identify the attacker, the mid-upper gunner thought he saw an aircraft pass from left to right moments before the attack.

Fire started to spread over the right wing. Ordering his men to bail out, Farrow held the aircraft steady until his six crew members exited the doomed plane. Then, with his plane almost upside down, he too bailed out.

The odds of surviving a crippled bomber in its death throes during World War II were about one in four. After the war, Rumpelhardt testified that in this particular instance the Halifax’s crew survived because Schnaufer’s Schräge Musik guns jammed at a critical moment, causing him to break off the attack.

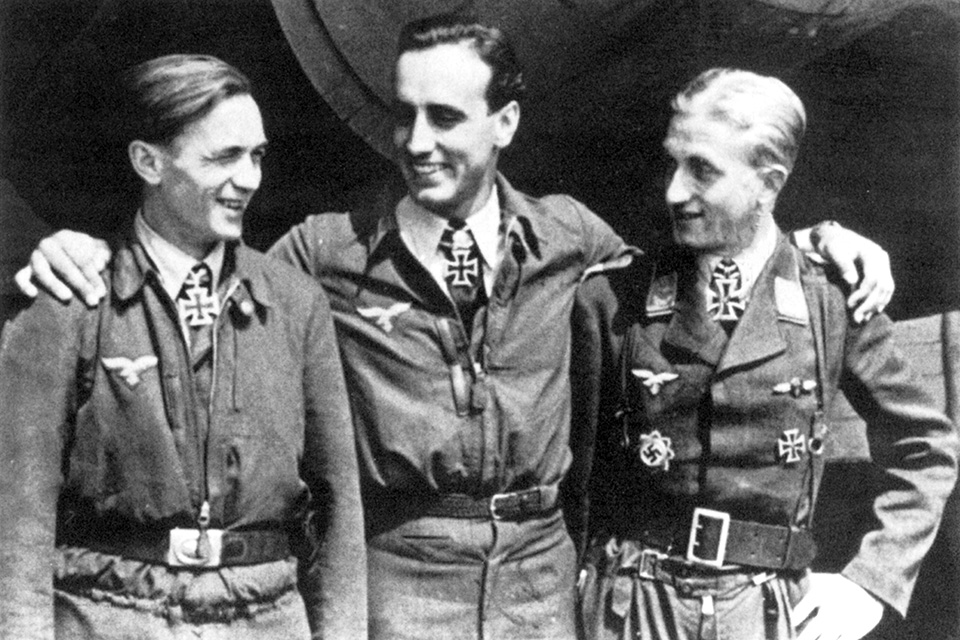

As the war ground on, with the German military machine collapsing on all fronts, the fate of the Luftwaffe was sealed. On May 4, 1945, surrender documents were signed for all German troops in northwest Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark. By that time Schnaufer and his crewmen had destroyed the equivalent of five complete squadrons, putting out of action approximately 850 Allied airmen, with an estimated 700 killed, 125 becoming prisoners of war and 25 evading capture and eventually returning to England. Apart from their impressive tally, Schnaufer, Rumpelhardt and Gansler constituted the only complete aircrew in the Luftwaffe to be awarded the Knight’s Cross.

With his country defeated, Schnaufer had the unpleasant task of making a final speech to the remaining men of NJG.4. In an emotional address, he recounted the wing’s proud record: They had shot down 579 bombers, but at a cost of 102 fighters as well as some 400 officers, NCOs and enlisted men, including 50 on the ground.

Schnaufer and his men were taken prisoner by the British in May 1945 at Eggebeck, NJG.4’s final base in Schleswig-Holstein. On their release later that year, Schnaufer returned to his hometown in Calw, then part of Allied-controlled Germany.

In 1946 Schnaufer and another German ace, Georg-Hermann Greiner, were arrested and imprisoned for six months after they illegally crossed the border into Switzerland. Hoping to continue flying in South America, the two had left Germany to try to initiate contacts within the outside aviation industry.

Schnaufer subsequently took over managing his family wine business and built it up to a very successful company. Wilhelm Gansler went to work for Schnaufer’s firm, while Fritz Rumpelhardt became an administrator at an agriculture college in West Germany.

The Schnaufer products are still highly regarded in Germany’s wine trade today. But in an ironic twist of fate, the skilled night fighter who survived the dangers of war was killed in France in 1950 by a speeding trucker. For a time there were stories that Schnaufer had actually been assassinated by members of the former French Resistance, but an independent autopsy found that his death had been an accident.

The former Nachtjäger is buried in Calw. The inscription on his gravestone reads: “Here rests the best and undefeated night fighter of the Second World War, Major and Wing Commander Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer 1922-1950.” There are also lines of verse, including: “Thee would I salute in the threshing of my wings / My heart foretells me triumph in thy name / Onward proud eagle, to thee the cloud must yield.”

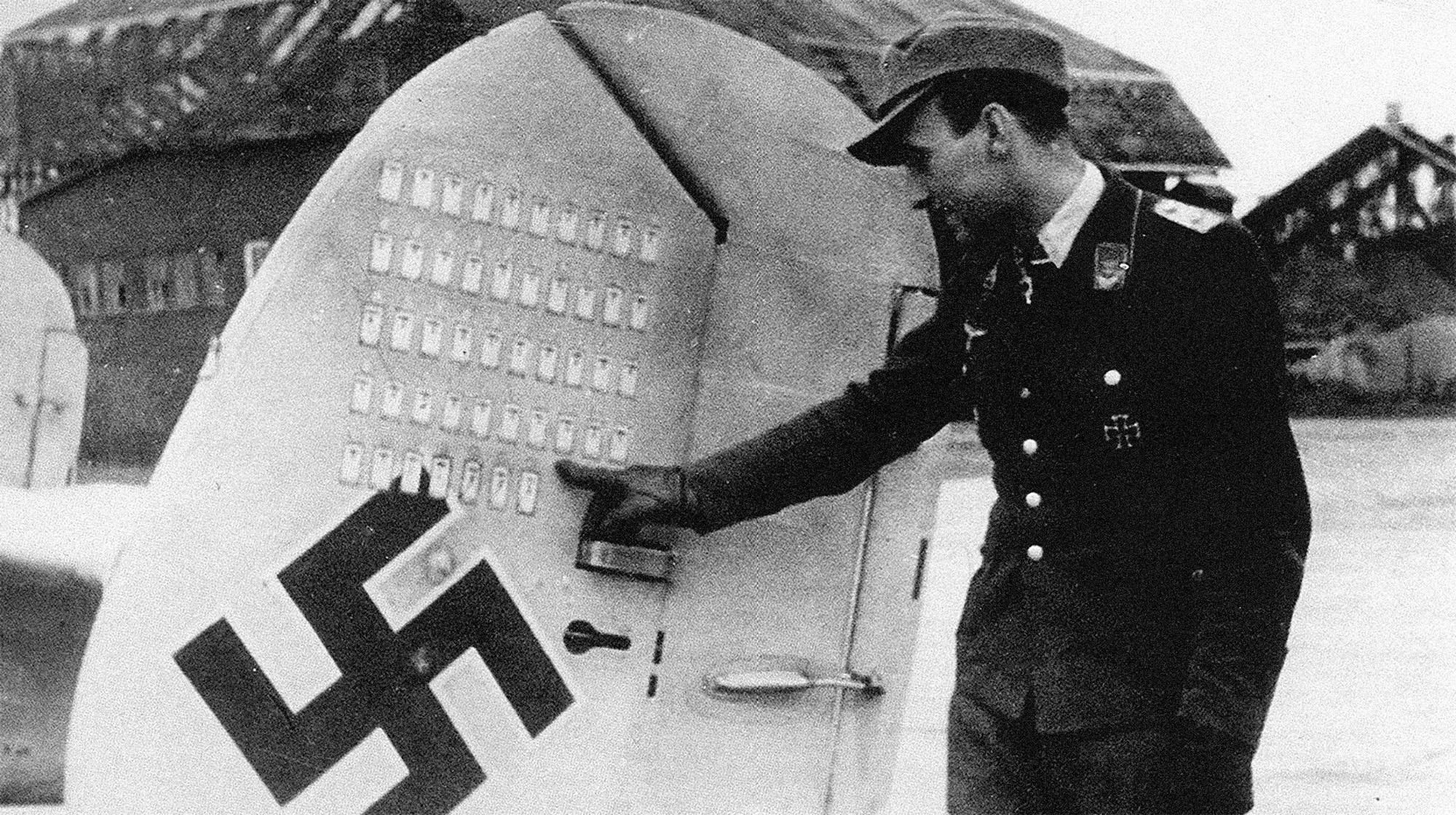

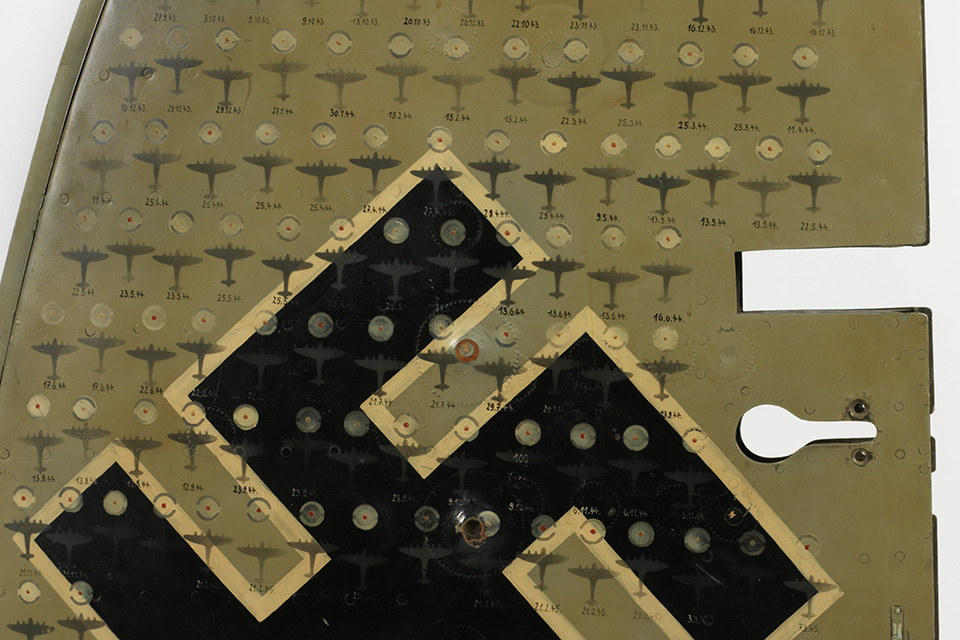

The right-hand vertical stabilizer of the last Me-110G-6 that Schnaufer flew is at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The left-hand stabilizer, apparently from that same plane, is in London’s Imperial War Museum. They both bear 121 symbols representing victories—a reminder of the tragic waste of life on both sides during WWII.

Originally published in the November 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.