New Smithsonian museum director see her task as making democracy relevant

In February 2019, Anthea M. Hartig became the Elizabeth MacMillan Director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. A third-generation Californian, Hartig previously was executive director and CEO of the California Historical Society in San Francisco. She holds a Ph.D. in public history from the University of California, Riverside.

Why does the National Museum of American History matter? We help people understand the promise, the power, and the fragility of the American experiment. Our greatest task is to make democracy relevant to the three to four million people who come here every year and the eight or so million we reach online. I tell my staff we’re the temporary stewards of some of the most important material objects that tell the story of the United States.

What’s your background? I have been lucky to become a public historian—learning conservation management, archival management, oral history, interpretive public art. Those tools coalesced in my two most recent positions, as Western regional director for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and with the California Historical Society, both based in San Francisco. At the Historical Society, I had a remarkable opportunity to reestablish the organization’s museum component and to begin to digitize the collection. We partnered with the State of California to create a “Teaching California” history curriculum and with the city of San Francisco to restore the 1874 Old U.S. Mint to serve as the society’s home and as a hub for community-based history activities. After we got to drive around in 1930s cars in conjunction with an exhibit on the 75th anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge’s opening, my sons told me, “Mom, you’ve got the best job ever!” When the Smithsonian called, I realized what an opportunity the National Museum of American History would be.

How will your preservation expertise inform your work? As an architectural historian, I am sensitive to complexities involved in preserving and re-enlivening the museum. My experience in cultural heritage provides me with a deep and layered understanding of the nature of our past as well as to the mid-century modernism of the museum’s physical building.

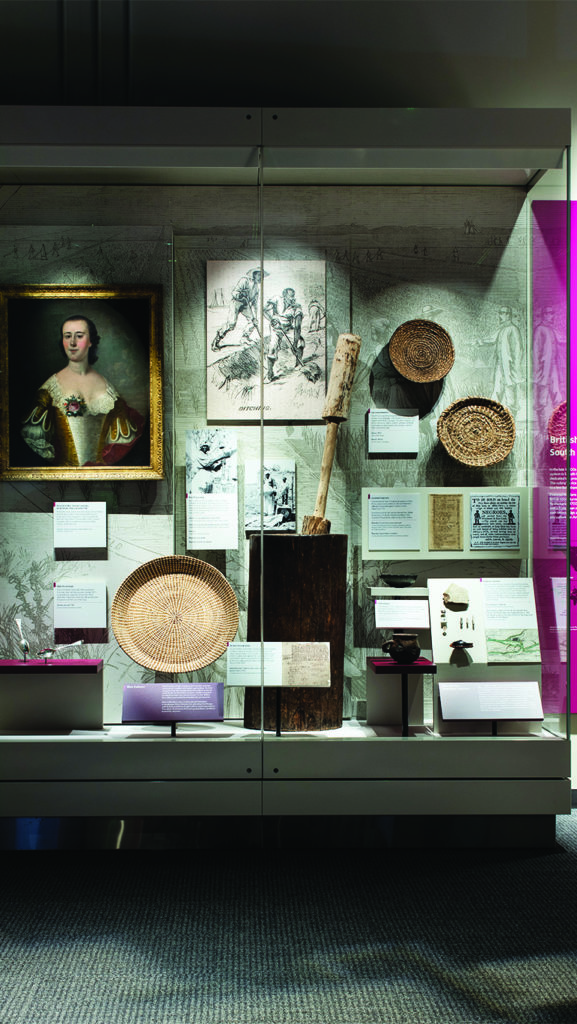

What exhibits evoke big responses? On our second floor, several exhibitions and spaces address the theme of “The Nation We Build Together.” In our “Many Voices, One Nation” exhibition, visitors find it compelling and very meaningful to follow the 500-year journey of how we became us, the United States. We see that it is a journey involving those who were here, those who came here, and those who were forcibly brought here. Throughout the exhibition, the symbol of Lady Liberty recurs, especially in the sculpture made by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers for a 2000 march for fair wages. The sculpture represents more than liberty. On her pedestal is a simple, powerful message from poet Langston Hughes: “I too, am America!”

The museum’s presentation on women’s history is dominated by Julia Child’s kitchen and first ladies’ gowns. Is that enough? This year we opened a petite but powerful exhibition called “All Work and No Pay,” which illuminates the truth that even if they didn’t hold paying jobs, women have always worked. We are working on two other women’s history exhibitions as part of the Institution’s American Women’s History Initiative, marking the centennial of the ratification in 1920 of the 19th Amendment granting women the vote. Our signature exhibition that opens next year and then travels around the nation is called “Girlhood! It’s Complicated.” We think it’s the first-ever in-depth exhibition about the trajectory of girlhood through time. “Girlhood!” will include artifacts ranging from Helen Keller’s “touch” watch, given to her by a retired diplomat, which allowed her to use her fingertip to feel what time it was, to the scarf 11-year-old Naomi Wadler wore when she spoke against gun violence at the March for Our Lives in March 2018. A third exhibition, “Creating Icons: How We Remember Women’s Suffrage,” will include objects related to leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association that were collected and brought to the Smithsonian just weeks after the amendment passed Congress. Susan B. Anthony’s shawl will be featured along with her portrait, which has not been on display here in over 50 years.

Tell us about the Molina Family Latino Gallery. I am thrilled that the museum will host the Smithsonian’s first-ever large display space dedicated to Latinx history. Just before I arrived at the Smithsonian, the Molina Family Foundation donated $10 million to create this gallery, which will end up comprising almost 5,000 square feet. It’s critical to understand that the histories of the first peoples of the Americas, Europeans, and Africans have been complicatedly and inextricably intertwined since the early 16th century, when Spain established St. Augustine, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico. The Smithsonian Latino Center is supporting a range of projects including one that will bring together artifacts and oral histories that are related to Spanish-language news media in the post-WWII United States. (During World War II, the Federal Communication Commission withheld licenses from Spanish-language radio stations licenses for fear that non-English programming could spread anti-American propaganda). In October 2020, a bilingual exhibition on Latinos in baseball—“Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues”—will open.

What is your vision? I want this facility to be the nation’s most accessible, inclusive, and relevant history museum. I want to reach people who learn in different ways, including online. And I want public history to reach the broadest possible audience. I am deeply heartened by the appointment of Lonnie Bunch, who was director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture and understands the importance of telling complicated stories, as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. We have a phenomenal challenge as we interweave stories with the broadest scope possible, and through them teach America’s past. As James Baldwin said in 1963, “American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

This interview appeared in the February 2020 issue of American History.