Puckish conservative ran short on votes but won the long game

William F. Buckley Jr.’s decision to run for mayor of New York City in 1965 as the Conservative Party candidate proved a turning point in his career and in the conservative movement. By challenging a charismatic liberal Republican and a bland Democrat in what was perhaps the nation’s most liberal city as President Lyndon B. Johnson was pressing to build his Great Society, Buckley invigorated conservatives across the country.

Buckley’s “paradigmatic campaign,” as he called it, sought to showcase conservative ideas as constructive alternatives to the liberal agenda. The National Review editor contested “group interest liberalism,” in which power brokers maintained control by placating voting blocs. That system, Buckley argued, perpetuated a stalemated status quo, as most voters had multiple interests. Addressing New Yorkers as individuals and talking about their city writ large, Buckley brought to bear wit, erudition, and theatricality, attracting more attention than normally accorded third-party candidates.

Buckley’s campaign had its origins in an appearance he made before the New York City Police Department’s Holy Name Society Communion Breakfast on April 4, 1965. His theme was the establishment of civilian review boards to investigate allegations of police brutality. Buckley opposed the imposition of such boards. Charges against police had been overstated, he said, positing that New Yorkers faced a greater threat from rising crime than from occasional police overreactions. He insisted that existing procedures might best address whatever abuses had occurred. Recent Supreme Court decisions, Buckley believed, had made it tougher for police officers to do their jobs.

The month before, the Alabama State Police had beaten civil rights marchers in Selma. The episode at the Edmund Pettus Bridge was very much on the minds of Buckley’s audience, the press, and the public. Buckley said events in Selma had “aroused” the “conscience of the world,” adding, based on information he later found to have been faulty, that television coverage of the episode had excluded footage of police showing restraint as demonstrators provoked them. Buckley might better have cited proven false allegations against police leveled locally.

The New York Herald Tribune reported the next day that Buckley’s audience had applauded his comments about the Alabama police and laughed at his references to the murder of civil rights volunteer Viola Liuzzo. Buckley remembered his listeners being silent during both passages. The New York Times, which mentioned neither applause nor laughter in its “bulldog” edition, a day later published an expanded story under the headline, “Buckley Praises Police of Selma/Hailed by 5,600 Police Here as He Cites ‘Restraint.’”

Unable to persuade the Herald Tribune to retract or modify its story, Buckley sued for libel. The Holy Name Society had recorded his talk; for members of the press, he played that tape, which documented the absence of applause and laughter. Clearly audible were Buckley’s references to “injustices” dealt African-Americans. Hearing the tape, the National Catholic Reporter wrote that of 26 quotations in the Herald Tribune story attributed to Buckley 19 were inaccurate. The Tribune agreed to correct the record. Buckley withdrew his suit. But the memory of how a single newspaper—however wrong its facts—could shape the narrative stayed with him. “Corrections very seldom catch up with distortions,” he observed. The manner in which the media covered his speech, as well as public figures’ demonstrated disinclination to counter such faulty reporting, lest it cost them votes, drove home to Buckley certain realities about municipal politics in the New York of that era.

Buckley later said he decided to run for mayor about 45 minutes after his April 4 speech; more likely, his decision flowed from the Herald Tribune incident. Another impetus was liberal Republican congressman John V. Lindsay’s contemplation of a mayoral run. Were Lindsay to win the mayoralty in a city where registered Democrats outnumbered Republicans three to one, Buckley surmised, commentators would declare Lindsay a contender for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination. That would reverse inroads conservatives had made in shifting the party’s ideological center rightward with the 1964 presidential nomination of Senator Barry Goldwater. This conservatives were determined to resist.

The night Goldwater lost, Lindsay had won a fourth term in Congress with 71.5 percent of the vote in a district LBJ swept. Lindsay’s campaign slogan, “The District’s Pride, the Nation’s Hope,” telegraphed his ambitions. New York’s Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller and fellow GOP moderate Jacob Javits, the state’s senior U.S. senator, both were thinking presidentially, and unlikely to leave office soon. Junior Senator Robert F. Kennedy had won election months earlier. In 1965, the mayoralty seemed the only way station that might open for Lindsay on the path he hoped to take from the House of Representatives to the White House.

Mayor Robert F. Wagner was retiring after 12 years at City Hall. The Liberal Party, which usually backed Democrats, was poised to endorse Lindsay, enlarging his prospects. As tribute for that gesture, the Liberals demanded Lindsay name one of their operatives to his ticket and award the Liberal Party a third of mayoral patronage. Lindsay entered the race with a record as one of the most liberal members of the House, with an 85 percent approval rating from Americans for Democratic Action. On May 13, 1965, Lindsay, 43, announced his candidacy for mayor.

Days later, Buckley, 39, published in National Review a column titled “Mayor, Anyone?” Proposing to lead New York City out of what he termed its “perpetual crisis,” Buckley described a 10-point program. He suggested measures to reduce juvenile crime. He advocated repealing narcotics laws regarding adults and allowing certified addicts to buy drugs at pharmacies. He favored legalizing gambling, exempting teens from minimum wage requirements, and ending union monopolies over city contracts. Businesses locating in depressed areas and hiring neighborhood residents would, under a Buckley plan, receive tax benefits.

To keep traffic moving, Buckley would ban loading and unloading of commercial vehicles between 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. He suggested that the city allow people with good driving

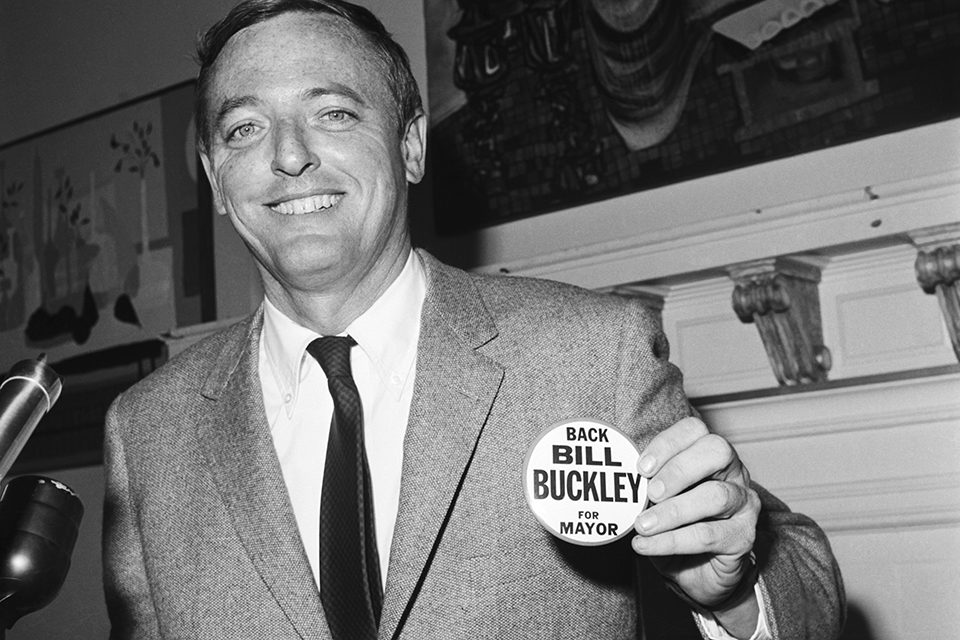

records to use their cars as taxis. His proposal to build a bikeway from 125th Street to 1st Street generated considerable interest. Buckley favored residency requirements for welfare and wanted to require recipients to perform some kind of work. In laying out the magazine, the managing editor added to the cover a teaser: “Buckley for Mayor?” On June 7, Buckley told Conservative Party chairman Daniel Mahoney he would accept the party’s nomination for mayor. At the Overseas Press Club on June 24, Buckley announced his candidacy. His opening line—that he often wished more of the press was overseas—got a sustained laugh. Buckley said he was running on the Conservative Party ticket because the Republican slot was closed to anyone not in the “mainstream of Republican opinion.” Lindsay and his managers countered that Buckley’s views were outside the “mainstream” of New York opinion. When someone inquired whether he wanted to be mayor, Buckley said he had “never considered it.” Asked how many votes he expected to receive, he replied, “Conservatively speaking: one.”

Most of the press editorialized negatively about his politics and his policy recommendations, but reporters covering Buckley found his ready humor, candor, and unconventionality refreshing. Liberal columnist and Lindsay supporter Murray Kempton, a friend of the candidate, said he found it reassuring that Buckley had pledged not to campaign during the day, given his duties at National Review, while incumbent elected officeholders would be campaigning on taxpayers’ time.

Buckley, asked the first thing he would do if he won, shot back, “Demand a recount!” His jest became the campaign’s most quoted line. Such witticisms tickled reporters and audiences; intimates feared Buckley was not taking his campaign seriously. He established credibility, however, by releasing well-reasoned position papers on virtually every issue. A commentator likened the volunteers crowding Buckley’s headquarters to “a ‘New Frontier’ elite of the political right.”

Lindsay sought to make a virtue of his newness to the New York municipal scene. His campaign advisers, taken with a Kempton line—“He is fresh, when everyone else is tired”—printed it on campaign posters. When not citing his personal attributes and professed idealism, Lindsay, by design, avoided specifics.

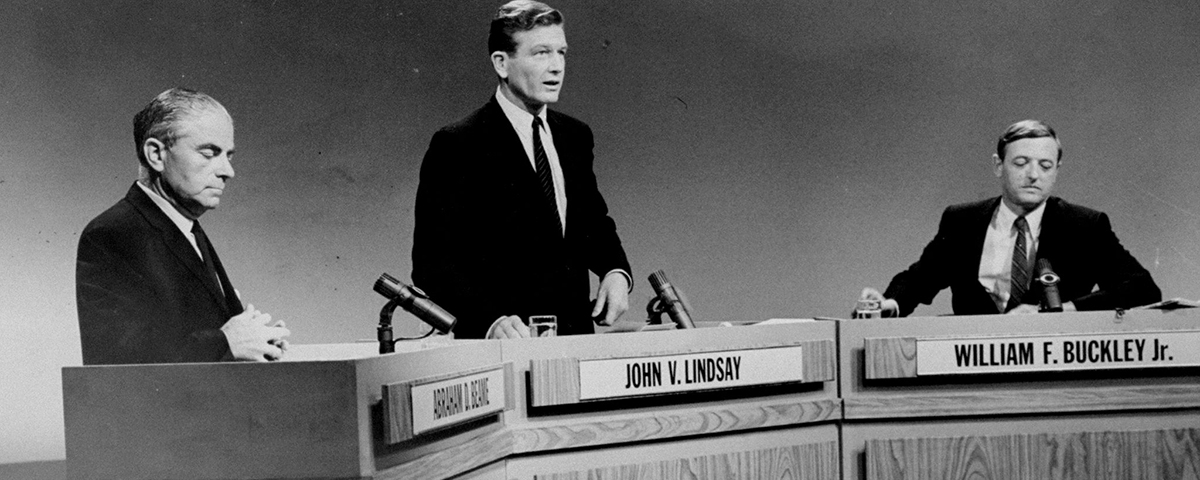

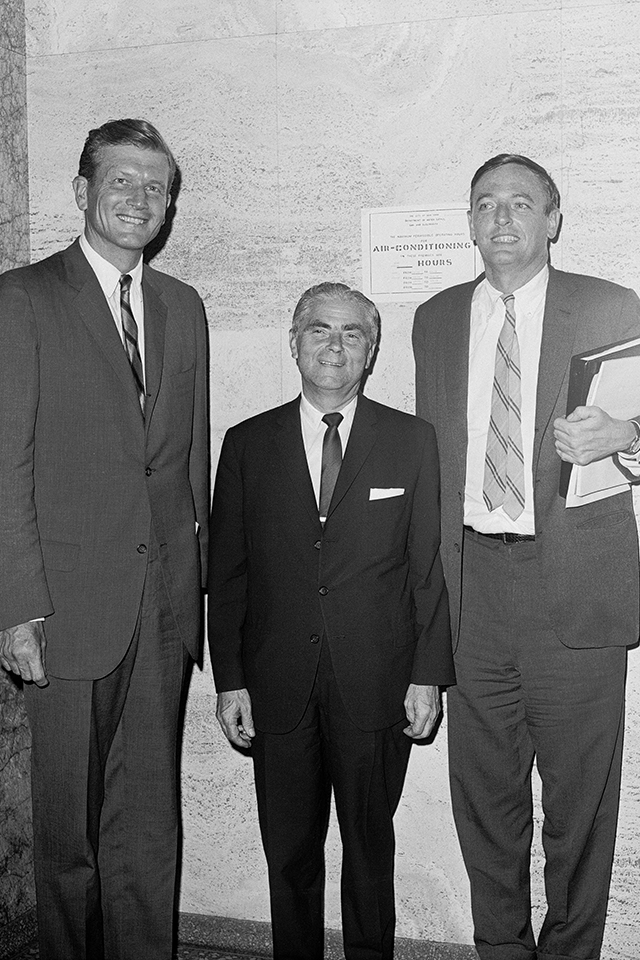

In September, city comptroller Abraham D. Beame, 59, won the Democratic primary. Asked to discern between the diminutive Beame and Lindsay, whom master builder Robert Moses likened to a matinee idol, Buckley pronounced their differences more “biological than ideological,” noting that he would be running against a tall liberal and a short liberal.

Averring disinterest in which rival he took votes from, Buckley was harder on Lindsay. He insisted that he bore the congressman no personal animosity, stating as his primary objection to Lindsay that he belonged in the Democratic Party. Indirectly nodding to Lindsay’s presidential ambitions, Buckley remarked, “Mr. Beame does not pretend to be anything but what he is, a very ordinary politician.” Lindsay denied having known Buckley when the two men were students at Yale and attributed Buckley’s different recollection to his suffering “delusions of grandeur.” An irked Buckley retorted that he did not take “grandeur” to mean “having known John Lindsay.” Whenever Lindsay donned reformer’s robes to batter Beame, Buckley, invoking Lindsay’s deal with the Liberal Party, proclaimed the Republican “boss backed.”

On September 16, Buckley caught a break when a strike shuttered six of the city’s daily newspapers. The 23-day walkout created a void that television, radio, and out-of-town papers filled, and which worked to Buckley’s advantage. Appearing together for the first time on radio, Beame and Buckley took aim at Lindsay from opposite directions. Beame said Lindsay, by not identifying as a Republican in his campaign literature, seemed to be ashamed of his partisan affiliation.

“I’ll buy that,” Buckley blurted, beckoning to Republican voters.

During the candidates’ first televised debate, Buckley, who at Yale had been a champion debater, employed techniques he had long since perfected, including scene-stealing. His facial expressions matched his rhetoric. Noting that Buckley had time remaining, the moderator asked if he cared to say more. “No,” the candidate said. “I think I’ll just contemplate the great eloquence of my previous remarks.”

In early October, a Herald Tribune straw poll had Beame leading Lindsay 45 percent to 35 percent, with Buckley at 10 percent. Within days, Buckley had jumped to 13 percent. On October 21, the Daily News, back in print, put Lindsay at 42 percent, Beame at 37 percent, and Buckley at 20 percent. Three days later, the newspaper poll had Lindsay at 43 percent, Beame at 40 percent, and Buckley at 18 percent.

Lindsay, playing to liberals, began to slam Buckley as an ultra-rightist, employing the phrase “relocation centers” to describe a Buckley proposal to move unemployed mothers on welfare to areas where the city would provide the women with housing and job training and their children with schools and recreation centers. Beame referred to Buckley as the campaign’s “Clown Prince,” asking rhetorically which groups Buckley intended to send to “concentration camps” once he removed all the welfare recipients and drug addicts.

Buckley was gaining among white ethnic voters, many of them Democrats, in the outer boroughs. Pollster Samuel Label attributed Buckley’s numbers to his “giving emotional voice to many racial discontents among white voters.” In framing his arguments, Buckley repeatedly mentioned Beyond the Melting Pot, a 1963 book by Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Glazer was a prominent Harvard sociologist; Moynihan, an academic on the rise in policy-making circles. As U.S. assistant secretary of labor, Moynihan had written a memorandum to President Johnson on the crisis besetting the black family: rising out-of-wedlock births, fatherless households, and increasing unemployment among black men—phenomena Moynihan said were exacerbated by a welfare system that stifled incentive and discouraged work.

Glazer and Moynihan also noted challenges to other ethnic groups in New York. The book’s chapter on Irish-Americans, which Moynihan wrote, told of how these and other outer-borough Catholic voters, once cogs of Democratic machines and prime beneficiaries of Tammany Hall largesse, had lost influence to “reform” Democrats. These “amateur Democrats,” as political scientist James Q. Wilson called them—were mostly upper-middle-class professionals and almost exclusively Protestant or Jewish. “Amateur Democrats” cared more about programmatic issues and programs, often run in Washington, than neighborhood problems and political patronage, the focus of the “regulars.”

This shift of power from clubhouse to reformers coincided with a surge of African-Americans and Spanish-speaking residents into the city and what has been termed white flight to the suburbs. Increasingly, regulars and reformers battled over school busing, public funding for private and parochial schools, crime control and prevention, taxation, abortion, civilian review of police, and accommodation to alternative lifestyles. Court decisions on school prayer, busing, abortion, and other matters intensified the sense in the white working class of losing influence. Buckley addressed these concerns.

“Either schools are places where education is the primary consideration,” the candidate declared, “or they are places where social policies of politicians are the primary consideration.” He predicted that “if the public schools became little more than social laboratories for the promotion of integration, parents most ambitious for the educational advantages of their children will, if they can afford to do so, send their children to private schools; those who cannot afford to do so will continue to send their children to the public schools but will become bitter, and even hostile, toward the minority groups whose pressures they hold accountable for unnatural arrangements.” He embraced vouchers—later rebranded “school choice”—as a means of relief for families unable to send children to private schools or better schools outside the city.

Many liberals dismissed Buckley’s comments on education and other issues as “racist.” Decades later, academician Timothy Sullivan concluded that outer-borough voters took to Buckley because they felt he understood their frustrations and treated them and their concerns with respect. This mutual attraction abounded with ironies. An elitist by temperament and a skeptic regarding democracy’s ability to remedy social ills, Buckley gave voice to grievances felt by a constituency little disposed to favor conservative economics and less hostile than he to government intervention elsewhere.

The phenomenon of Buckley’s appeal to primarily white, working-class voters persists. “Buckley Democrats” shared demographic and other characteristics with Nixon’s “silent majority,” “Reagan Democrats,” and “Trumpers.” Buckley and his advisers expected him to do best among Republicans concerned about rising taxes and a declining city economy. Few even within his own camp expected Buckley to draw working-class voters away from their Democratic roots. Voters among whom Buckley was making inroads could not have cared less whether he or Lindsay represented the GOP’s future.

Nor did Buckley ignore African-Americans. He traced racial animus in New York “in part to a legacy of discrimination and injustice committed by the dominant ethnic groups. The white people owe a debt to the Negro people against whom we have discriminated for generations.” To right historic wrongs, Buckley embraced what later went by the name of affirmative action. He promised to crack down on unions that discriminated against African-Americans. Appealing to black individuality, Buckley declared educational success, bootstrapping, and capital formation surer avenues out of poverty than government programs.

Four days before the election, Buckley visited the offices of The New York Times. He recalled secretaries, janitors, and non-editorial staff enthusiastically welcoming him, in contrast to the cool response of the paper’s editorial board. He told reporters afterwards that he felt, upon exiting the building, as if he had passed through the Berlin Wall. Asked what he would do if he woke up mayor, Buckley replied, “Hang a net outside the window of the [Times] editor.”

Lindsay won with 45.3 percent to Beame’s 41.3 percent and Buckley’s 13.4 percent. Between them, Lindsay and Buckley won 57.8 percent of the vote. As Buckley had anticipated, news reports began to name Lindsay a presidential possibility. The commentariat’s refrain was that Buckley, by failing to deny Lindsay victory, had not figured in the election, except insofar as he pulled votes from Beame, enhancing Lindsay’s tally. Another explanation was that traditionally Democratic voters made a conscious decision to deviate from past voting patterns.

Buckley polled worst in Manhattan, taking 7 percent to Lindsay’s 55.8 percent and Beame’s 37 percent. He did best on Staten Island, receiving 25.2 percent to Lindsay’s 45.8 percent and Beame’s 28.9 percent. Buckley polled 21.9 percent among Irish-Americans and 17.8 percent among Italian-Americans.

Buckley’s percentage belied the growing and enduring impact he would have on American politics long after both of his opponents, each elected New York’s mayor, had departed the scene. He emerged as the best-known American conservative after Barry Goldwater.

Fan mail inundated his office. Strangers stopped him to have pictures taken and to request autographs. National Review subscribership jumped to 117,000. His newspaper column, “On the Right,” had been running in 150 papers; that figure doubled.

Buckley’s byline began appearing more frequently in Esquire, Playboy, The New York Times Magazine, and other periodicals besides his own. He became a favorite and frequent guest on The Dick Cavett Show and The Tonight Show. He appeared on the prime-time revue Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In and on satirical programs hosted by Woody Allen. He began publishing books at the rate of at least one per year, many of them best sellers.

And Buckley launched his own weekly public affairs television program, usually featuring him matching wits with a liberal intellectual or activist. Debuting less than three months after Election Day, Firing Line ran for 33 years, making Buckley’s a household face.

The Buckley persona became recognizable to millions. Two years after Buckley’s mayoral run, Time ran a cover story, “William F. Buckley, Jr.: Conservatism Can Be Fun.” Presidential hopefuls sought his endorsement.

Buckley likely never would have attained such prominence, or its accompanying influence, had he not run for mayor. Among his many new roles was that of “tutor” to Ronald Reagan, who, a year after Buckley’s “paradigmatic” campaign, won the California governorship. Days after the 1965 New York City mayoral election, Barry Goldwater proclaimed that Bill Buckley had “lost the election but won the campaign.” More than a half-century later, those words appear even more prescient than they did then.