Being hauled into the dock is not unheard of

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]HE MILLS OF THE LAW, like those of God, grind slowly, but they grind small. Donald Trump’s enemies and accusers hope to involve him in lawsuits that will tenderize him in court.

This spring a U.S. District Court judge ruled that the attorney general of the District of Columbia may sue Trump on the grounds that rents foreign diplomats pay for rooms in his hotel in the Old Post Office on Pennsylvania Avenue NW represent unconstitutional gifts. The alleged unconstitutionality arises from the stern words of Article I, Section 9: “no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under [the United States] shall…accept of any present [or] Emolument…from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

A New York State Supreme Court judge ruled that Summer Zervos, a contestant on Trump’s reality show The Apprentice, could sue him for defamation. Trump called Zervos a liar during the homestretch of the 2016 campaign after she accused him of groping her in 2007. “No one,” the New York judge intoned, “is above the law.” Another U.S. District Court judge let Trump off the hook, denying a motion to depose him by pit-bull lawyer Michael Avenatti. Avenatti represents porneuse and ecdysiast Stormy Daniels, who has sued to overturn an agreement she made to keep mum about an alleged 2006 fling with Trump. The judge called Avenatti’s motion “premature.” The attorney vowed to return with new motions.

English kings occasionally were murdered or killed in battle by upstarts, but custom and an aura of near-mystical respect kept monarchs from being dragged into court. Was America’s president meant to enjoy similar immunity from prosecution? From testifying in other people’s cases? The Constitution says Congress may impeach a president and remove him from office for the sonorous if vague offense of high crimes and misdemeanors. But can a president also be subject to ordinary legal proceedings?

The founders weren’t sure. In 1789, during the inaugural session of the First Congress, Vice President John Adams and Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay had an impromptu cloakroom debate on the subject. The president, declared Adams, “was above the power of all judges.” Otherwise, any troublemaker in a black robe could entangle the chief executive in a prosecution that might “stop the whole machine of government.” But, Maclay asked, suppose the president “commits murder in the streets?” Impeach him and indict him, answered Adams. Maclay pressed on: “Suppose he continues his murders daily” and Congress is not in session to impeach him? The people would rise up to stop him, Adams exclaimed. So, Maclay concluded, we should rely on a mob to do what the legal system can’t? Too bad there were no high schools—Maclay would have been a star debater.

The issue grew from bull session to reality in 1807 with Aaron Burr’s trial for treason. Burr had been vice president during Thomas Jefferson’s first term, but his evident ambition caused Jefferson to drop him from the ticket in 1804. Burr spent his newfound free time traveling the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, promoting a settlement in Arkansas. In January 1807, President Jefferson learned that Burr was up to something darker: James Wilkinson, commanding general of the U.S. Army, claimed that Burr planned to lead 7,000 men to seize New Orleans, invade Spanish Mexico, and start a nation. Wilkinson’s evidence was a coded letter from Burr inviting the army commander to join the plot.

Jefferson told Congress that Burr’s guilt was “beyond question,” and ordered his arrest. The “invasion force” amounted to 60 men. The scheme’s staging area had been an island in the Ohio River, so Burr was tried in Richmond U.S. Circuit Court, whose senior judge was Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall.

The trial was a circus. Richmond overflowed with spectators; nine lawyers—three for the prosecution, six for the defense—wrangled endlessly. The

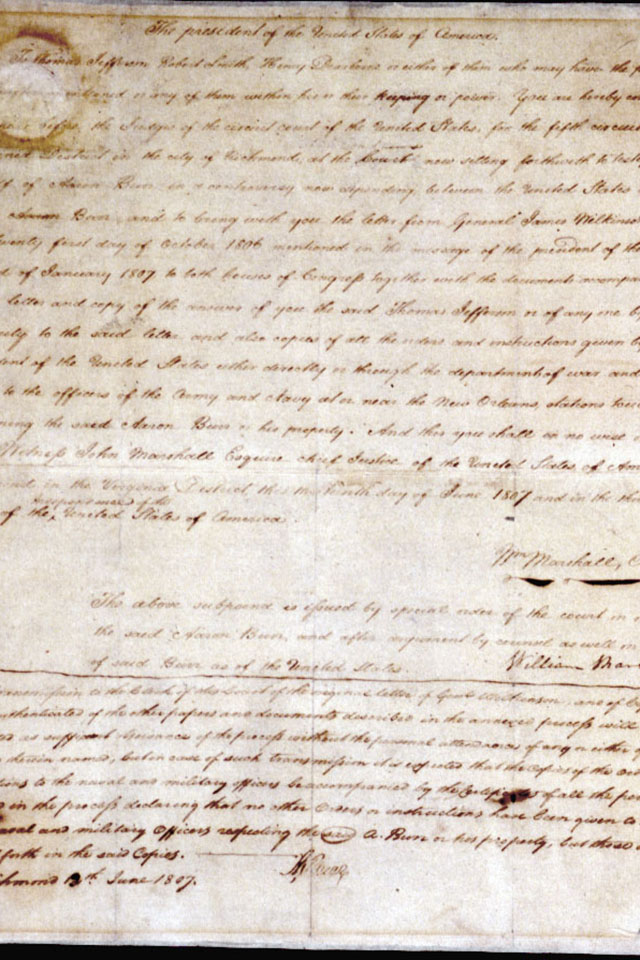

government was prepared to call 140 witnesses to Burr’s general awfulness. In May, the defendant enlivened the proceedings by asking Marshall to subpoena the president. Burr wanted Jefferson to come to Richmond bearing the original of the coded letter.

Lawyerly polemics reached gale force. Most eloquent was Burr’s senior attorney, Luther Martin, a veteran of the Constitutional Convention, an iron-lunged orator, and a high-functioning alcoholic. Jefferson, Martin stormed, “has let slip dogs of war, the hell-hounds of persecution.” If the president now withheld “information that would save the life of a person, charged with a capital offense,” he would be “a murderer, and so recorded in the register of heaven.”

Marshall ruled on Burr’s request in June. “The court,” he declared, “would not lend its aid” to frivolous motions. However, defendants did have “the right of preparing the means to secure…a fair and impartial trial.” Marshall issued the subpoena.

Jefferson’s response denied the form while conceding the substance. He declined to appear in court. “To comply” with such a request “would leave the nation without an executive branch,” he said. But Jefferson told his attorney general to let Burr see the coded letter. Privately Jefferson steamed; he wanted Luther Martin indicted as a co-conspirator. Prosecutors in Richmond wisely ignored this specimen of premature Nixonianism.

After all this, the coded letter did not figure in the trial; modern scholars doubt Burr even wrote it. He walked because the government could not prove he had committed treason.

Jefferson was off-stage pulling wires in Burr’s case. But suppose the president himself is a party? In 1994 Paula Jones sued Bill Clinton, claiming he had sexually harassed her when he was governor of Arkansas and she a state employee. The president’s lawyers countersued to stop the action, on the grounds that allowing to suit to proceed while Clinton was in the White House would pose “serious risks for the institution of the Presidency.” They cited Adams’s off-the-cuff judgment in 1789, and Jefferson’s refusal to go to Richmond in 1807, and asked the court to delay Jones’s suit until after Clinton left office.

The Clinton team’s argument came before the Supreme Court in 1997. Justice John Paul Stevens, delivering the opinion of the court, found no guidance in the past, since Adams and Jefferson said “tomato” while Maclay and Marshall said “tomahto.” Examining the argument on its merits, Stevens decided that postponing Jones’s suit would burden her, since delay would fog memories and erode evidence. Letting the case proceed would not burden the president, since “it appears to us highly unlikely to occupy any substantial amount of [his] time.” The Supreme Court let Jones sue. Her lawyers asked Clinton if he had had sex with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Clinton’s denial, under oath, began a circus that made Burr’s trial seem like a Quaker meeting.

The president may be the most powerful man on earth, but he can be compelled to give evidence or testimony on his behalf, or on behalf of others. The lawyers circling Trump no doubt hope to entangle him under oath in a Clintonesque contradiction. Be careful what you ask for. Jefferson’s day in court left him looking like an unsuccessful bully. Clinton’s left him looking like a bullied sexual everyman.

All it cost him was time.