In the thick of presidential primary season, Republican candidate Donald Trump canceled a rally at the University of Illinois in Chicago because of the number and vehemence of protesters in and out of the hall. “We shut shit down!” demonstrators shouted. “We stumped Trump!” A Chicago police officer took a thrown bottle in the head.

A Trump campaign statement calling off the rally asked everyone to “please go in peace.” But for months, Trump himself had been making incendiary remarks about hecklers at his own events. “If you see somebody getting ready to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of them, would you, seriously,” the candidate told supporters in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in February. “I promise you, I will pay for the legal fees.”

The First Amendment is designed to protect freedom of speech and of the press from overbearing government. “A bill of rights,” as Thomas Jefferson put it, “is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth…and what no just government should refuse.” But historically in America, government has not been the only censor; bullying mobs can shut down free expression as effectively as any bureaucracy and have been doing so for more than 200 years. In 1787-88, mob violence even marred the struggle to approve the Constitution. The framers ratified our fundamental law in an atmosphere that sometimes slipped into lawlessness.

The first such episode occurred in Philadelphia in September 1787, days after delegates to the Constitutional Convention finished their work. They signed the document in the State House (now known as Independence Hall) on September 17. The next day, the Pennsylvania Assembly—the state’s unicameral legislature—met in the same room to hear a public reading of the new instrument. The framers had stipulated that the Constitution take effect once it had the approval of nine states; Pennsylvania—one of the largest—was considered a must-win. The Assembly ordered 3,000 copies printed (2,000 in English, 1,000 in German) for the public’s edification and heard a motion to call a state ratifying convention.

The call for a convention struck assemblymen representing central and western Pennsylvania as too much, too soon. Their state’s vast distances and mountainous interior meant that their constituents would be weeks learning what the new Constitution said. At the end of September, enough skeptical assemblymen absented themselves to deprive that body of a quorum—until, in a sweep of Philadelphia boarding houses, the sergeant-at-arms ran to ground two no-shows. A contemporary observer described the result: “After much abuse and insult,” the reluctant assemblymen were “dragged through the streets to the State House” and kept there “by force.” Quorum in place, the Assembly issued a summons for a ratifying convention that went on to approve the Constitution in December.

The debate spilled into 1788, with the Federalists winning easy victories as well as close calls. The Massachusetts ratifying convention, which sat in January and February 1788, was a model of tough-minded, reasonable argument. Discussion in Virginia’s ratifying convention, which did not meet until the beginning of June, was more heated but intelligent and principled.

It was in New York that mobs made an appearance. Politics in New York had been rough since colonial times, when merchants and supporters of the established Church of England contended with landowners and other Protestants in the elective lower house of the legislature. During a 1769 election, a member of the landed Livingston clan boasted, “We have by far the best part of the bruisers on our side.”

During the Revolution, the pro-Anglican party turned Tory and thereafter faded. The triumphant landowner group then split in two, with older families—the Livingstons and the equally prominent Schuylers—opposing Governor George Clinton, a son of Irish immigrants. Ironically the new man, Clinton, championed the status quo, resisting the new system of government as a threat to his power, while the old families, led by the Schuylers’ young in-law, Alexander Hamilton, were advocating for reform and the Constitution.

New Yorkers debated briskly. The city’s five newspapers—the New-York Journal being the most virulently anti-Federalist—filled their pages with arguments pro and con. “Brutus” (pen name of Robert Yates, a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention who had walked out in disgust) arraigned the Constitution, while “Publius” (a collective pseudonym of Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay) analyzed and defended it.

“All we hear is…Constitution talk,” a New Yorker wrote in the spring of 1788. That talk continued at New York’s state ratifying convention, convened on June 17, 1788, in Poughkeepsie. Governor Clinton led the anti-Federalist majority. Hamilton and Robert R. Livingston, head of his clan, eloquently challenged Clinton and company, while Jay patiently offered them deals. But on the streets, bruisers also were playing a part.

On July 3, Albany got word of a decisive moment.

A ninth state, New Hampshire, had ratified at the end of June; now Virginia, the largest state, had signed on. Happy Federalists rang church bells and fired guns. But on July 4 anti-Federalists, determined that New York should decide its own destiny, marched to a vacant lot where they ceremoniously burned a copy of the Constitution. Later that day, hundreds of Federalists affixed another copy to a felled pine tree and paraded the document through town. As Federalists passed the tavern where their foes maintained their headquarters, the pub’s occupants hurled bricks, rocks, and scraps of iron. In retaliation, the Federalists trashed the building and took prisoner some of their assailants, including the mayor’s brother.

Bowing to the national trend, the Poughkeepsie convention finally ratified the Constitution on July 26.

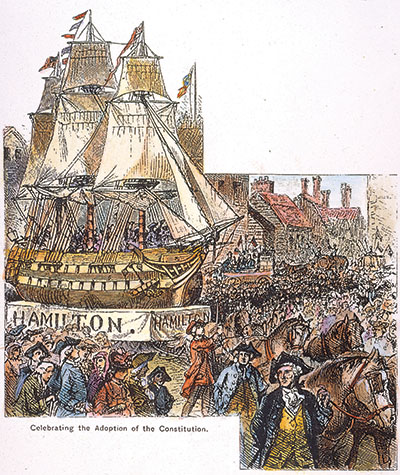

When that news reached New York City, Federalists fired salutes from Fort George in the harbor and from the deck of the “Hamilton,” a 27-foot float in the shape of a ship, moored at Bowling Green. After dark, the celebration turned sinister. Five hundred men attacked New-York Journal publisher Thomas Greenleaf’s home. The crowd smashed Greenleaf’s windows, then advanced on Clinton’s residence and the home of prominent anti-Federalist John Lamb.

Fortunately, in none of these incidents was anyone killed. The sergeant-at-arms waylaying the Pennsylvania assemblymen in Philadelphia only roughed up and humiliated the pair. The anti-Federalists who had been seized in Albany were soon released.

In New York City, Greenleaf escaped the mob by fleeing out his back door. Clinton was not at home, and Lamb had barred his windows and armed himself, which cooled the crowd’s enthusiasm. But force did succeed in stifling free expression. The Pennsylvania assemblymen were compelled to count themselves present. Greenleaf’s attackers not only vandalized his home but also threw his type into the street. In five days, the New-York Journal had resumed publication—not daily, but weekly.

It is to the country’s credit that such episodes were the exception. Most Americans who were involved in ratification, from leaders to ordinary voters, took the issues seriously and behaved responsibly.

As Pauline Maier wrote in her book Ratification, “‘We the People’ of 1787 and 1788” were engaged in “a dialogue between power and liberty,” not a brawl.

But the bruisers remained on call even after the Constitution was up and running.

When the Livingstons did not receive one of New York’s seats in the new national Senate, they turned on Hamilton; their rejection helped demote him from home-state and hometown hero to goat. In 1795, trying to address a hostile mass meeting on Wall Street, Hamilton was hit in the head by a stone. Making a joke about “knock-down” arguments, he left the scene.

Memo to municipal police departments across the land: A lifelong New Yorker, fellow name of Trump, is running for president.✯

This story was originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.