“I never imagined I was going to be doing this when we launched,” said Captain Earl Ehrhart of U.S. Marine attack squadron VMA-231 (“Ace of Spades”) aboard the Marine landing ship Bataan (LHD-5). The vessel’s crew had been looking forward to the end of their deployment when Hamas made its mass incursion from Gaza into Israel on October 7, 2023, slaughtering about 1,200 civilians and kidnapping 253.

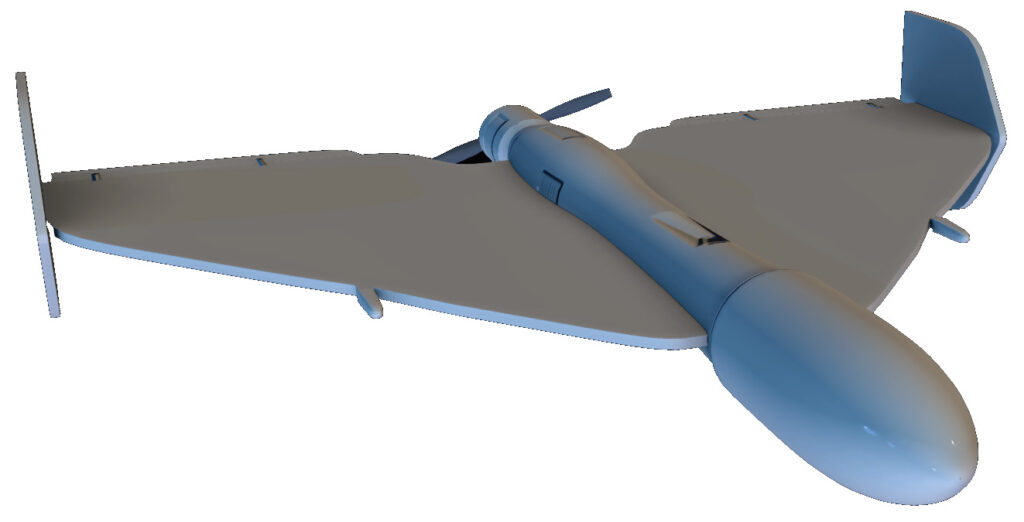

With that, Bataan’s deployment was extended and the ship dispatched to the eastern Mediterranean while Israel Defense Forces launched a draconian counterattack into Gaza. Shortly afterward, Houthi rebels, a Yemeni militant group armed by Iran, began launching Iranian-produced Shahed (“witness”) 136 explosive drones at every cargo ship they regarded as being owned or associated with Israel or the United States that entered the Red Sea via the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. (However, on February 12, 2024, the militants targeted Star Iris, a Marshall Islands-flagged bulk carrier full of corn bound for Iran, for all intents and purposes making the Houthis’ show of solidarity with the Palestinian refugees in Gaza a declaration of war against the world.) In reaction, the Bataan transferred to the Red Sea to use its AV-8B Harrier II vertical-takeoff-and-landing fighter-bombers in defense of the endangered merchantmen.

For Earl Ehrhart V in particular, things were about to get controversial. In a BBC interview on February 12, 2024, Ehrhart stated that since December 2023 he had personally destroyed seven drones before they could strike. “The Houthis were launching a lot of suicide attack drones,” he said. “We took a Harrier jet and modified it for air defense. We loaded it up with missiles and that way, we were able to respond to their drone attacks.” Ehrhart’s claim of seven Shaheds revived a debate of sorts that has been going on since World War I: should this kind of aerial victory be equal to the downing of a manned airplane? And if so, does downing more than five of them make Earl Ehrhart the first American ace since 1972?

Although the Harrier’s primary mission involves ground attack and troop support, its British predecessor, the British Aerospace Sea Harrier, had demonstrated its air-to-air capabilities during the 1982 Falklands War, shooting down at least 20 Argentine fighter-bombers without loss. This astounding kill-to-loss ratio was primarily due to the Argentines’ lack of an airbase between their home bases and the Falkland Islands, depriving them of the loiter time to engage the British fighters and limiting their options to attacking the British ships before hightailing it for home. Being remotely controlled unmanned aircraft, the Shahed-136s were likewise unable to fight back against intercepting fighters and had the added handicap of a maximum speed of 115 mph. They also cost only $20,000 apiece and could be produced in great numbers and dispatched en masse. To deal with them, Ehrhart and his VMA-231 colleagues were often guided to their targets by the radar of accompanying warships and attacked the drones with AIM-120 AMRAAMs (advanced medium range air-to-air missiles) or AIM-9M Sidewinder heat-seeking missiles. In spite of the inherent disparity between a piloted fighter and an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), the low altitudes at which the UAVs could fly over the water could make them difficult targets for the Sidewinders. The more sophisticated AMRAAM was far more likely to score a hit, but at a monetary cost many times that of a Shahed. (The AV-8B could also carry a 25mm GAU-12/U Equalizer automatic cannon and 300 rounds.)

Airplanes have been shooting down other airplanes since 1914, and by 1916 lighter-than-air craft, such as kite balloons and Zeppelin airships, were added to the “fair game” menu. By observing the front and directing artillery fire, balloons became tactically viable targets. Attacking one could be dangerous, too—they may have lacked their own armament, but they were encircled by anti-aircraft guns and located far behind enemy lines. The Zeppelins bombing British cities were armed, although they relied more on high-altitude climbing to escape interception.

Another aspect of air-to-air combat that was generally settled upon was that a victory scored by more than one airplane would be shared by all involved and go down as a whole victory in each pilot’s logbook. The main exceptions to this were the Germans, who generally stuck to one pilot, one victory, while British policy on the matter followed an inconsistent course. Also during World War I, a victory scored by a two-seater reconnaissance plane or bomber would be shared between the pilot and his observer, who was usually manning a machine gun or two of his own.

While one-on-one combat ending in a crash or an adversary in flames makes exciting fodder for the movies, a high percentage of “kills” in aerial combat were “moral victories” involving an enemy going down OOC (out of control) or being FTL (forced to land). More aircraft since World War I were “shot up” than “shot down,” but still counted in good faith as a victory. Postwar access to enemy records usually reveals that their real losses were only a fraction of what their adversaries had reported. Aces with complete matches to their claims have always been exceptions to the rule, known examples being Americans Douglas Campbell (six in World War I) and Steve Ritchie (five over Vietnam) and North Vietnamese aces Nguyen Tien Sam (five) and Nguyen Duc Soat (six).

By World War II the warplane had matured considerably, and single combat had largely given way to sprawling air battles, which added a few more variations to the tallying process. Some, like Britain, the United States and Finland, logged each pilot’s victory in fractions if more than one were involved in a shoot-down. As Allied bombing raids became an increasing threat to the Axis war effort, Germany, Romania and Bulgaria introduced a point system to encourage their fighters to brave the huge bomber wings. Pilots received one point for a single-engine airplane, two for twin-engines and three for four or more. Many fighter pilots from those three air arms kept tally of separate scores, realizing that the point system was a way to get medals but also likely to invite post-war skepticism over claims.

UAVs first appeared in the form of the German Vergeltungswaffe (“vengeance weapon”) V-1 against British cities in June 1944. The V-1’s debut led to the question of its status as an aircraft. These “divers” or “doodlebugs” were a serious menace to life and industry and had to be eliminated, and they also presented intercepting Allied fighter pilots with the threat of serious damage or destruction if they exploded in their faces. A safer prospect of eliminating the V-1 was for the pursuer to slip a wingtip under the enemy’s and raise it to upset the gyro-based guidance system, causing the V-1 to crash in a relatively less vulnerable open area. In spite of the special challenges the V-1 presented, the Royal Air Force chose to put multiple-scoring “diver aces” into a category separate from those who downed manned aircraft.

The United States used AQM-34 jet-powered reconnaissance drones over Vietnam, and North Vietnamese fighter pilots sometimes intercepted these swift, elusive little targets—and sometimes, while chasing them over the hilly terrain, crashed in the process. Many North Vietnamese counted the destruction of drones in their scores, including two by their nine-victory ace of aces, Nguyen Van Coc. The Americans at that time were not inclined to count them as such and U.S. Air Force ace Steve Ritchie made his own opinion known in an interview: “I don’t count robots.”

Since the Vietnam War, however, advances in technology have brought a new generation of UAVs into play, guided by operators thousands of miles away. The possibility of dueling drones dogfighting for local control of the sky while being flown from office chairs in faraway control centers is no longer science fiction, which seems to be what the USAF had in mind in 2017 when it revised its criteria for air-to-air combat: “The Air Force may award an aerial victory credit to an Air Force pilot or crew that destroys an in-flight enemy aerial vehicle, manned or not, armed or not.”

Which brings us full circle to 2024, in which, according to the USAF, Nguyen Van Coc retains his place as Vietnam’s ace of aces and Captain Earl Ehrhart V, USMC, credited with seven Shahed-136 attack drones, rates as the latest American ace.