The ragged force of 250 French Canadian, Abenaki, Huron and Mohawk warriors hunkered down in the snowy underbrush just before midnight on Feb. 28, 1704. They wrapped their blanket coats and furs tightly about themselves and kept careful watch for any signs their presence had been detected. The men had arrived at a frozen meadow just north of the village of Deerfield, in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, after an arduous journey of more than 300 miles on snowshoes from Chambly, Quebec. Although they surely smelled the wood fires burning in nearby hearths, the warriors could only huddle together for warmth—campfires would risk the all-important advantage of surprise. They chewed on the last of the dried pemmican and corn to ease the gnawing in their bellies. If everything went according to plan, they would all soon eat their fill from the kitchens of New Englanders.

While some warriors quietly chanted tribal war songs, others, particularly the French Canadians and their Roman Catholic Mohawk and Huron allies, whispered Christian prayers for the success of their raid against the heretic English Protestants. For the French and some warriors the expedition was a religious crusade, encouraged by Roman Catholic priests in New France. For the Mohawks the raid also offered the promise of captives to be adopted into their clans. For some of the Abenakis the attack would serve as vengeance against the English for having been evicted from their lands. All warriors looked forward to the rewards of plunder and the wealth the sale of captives could bring.

In the predawn darkness Lieutenant Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville, the expedition’s French Canadian commander, quickly dispatched scouts to observe the sleeping hamlet. The 35-year-old Hertel was the son of renowned bush fighter Joseph-François Hertel de la Fresnière. The younger Hertel was no stranger to frontier partisan warfare, having accompanied his father on raids against the English settlements of Salmon Falls and Casco, in what today is Maine, and Schenectady, N.Y. But this was his first command.

Philippe de Rigaud, the Marquis de Vaudreuil and governor general of New France, had ordered the raid deep into New England. His instructions were in keeping with directives from the court of Louis XIV to conduct offensive actions that would strike terror into the English and deter their territorial expansion in North America. The expedition had the secondary goal of drawing northern tribes into the broader struggle between the European powers by binding them to the French through plunder, captives and bloodshed. On a more personal level, Hertel hoped a successful outcome would finally convince the Crown to approve his family’s petition for nobility, a request previously denied due to his father’s lack of wealth. As he waited in the darkness, however, Hertel must have been singularly focused on ensuring the war chiefs of the various tribes, as well as his French Canadian subordinates, clearly understood the plan of attack.

Ensconced within Deerfield’s stockade walls, the Rev. John Williams lay in bed beside his wife, Eunice. He had likely read Bible passages to his seven children as they gathered around the blazing stone hearth after dinner. Perhaps the Williams’ slaves, Frank and Parthena, and the pair of militiamen quartered in the house had joined them by the fire until it was time for bed.

They and their fellow townspeople slept soundly. True, back in October two settlers working in the fields outside the village had been captured by marauding warriors, stoking fear. But such risk was part of the price Deerfield’s 270 inhabitants were willing to pay for fertile farmland on the western fringes of Massachusetts. Months had passed with no attacks.

Not to say townspeople were complacent. Reasonable precautions could reduce the risk of French and Indian attack, and the Rev. Williams and other prominent leaders had petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature for protection. Indeed, it was in the best interest of Massachusetts, as well as Connecticut, to defend Deerfield and other frontier settlements rather than do battle with raiders in the streets of Boston or Hartford. The Legislature duly dispatched soldiers to Deerfield and approved a tax abatement so the town could repair the crumbling wooden stockade that enclosed the heart of the village. Connecticut also sent troops.

Periodic reports about a large force of French and Indians assembling near Montreal had reached Deerfield as early as the summer of 1703, but there had been scant enemy activity, other than the autumn marauders. Subsequent reports generated fresh anxiety, but the rumored threats never materialized, and Massachusetts and Connecticut had ultimately withdrawn their forces. Finally, the leaves turned crimson and gold, temperatures dropped and the snow fell.

By the morning of February 29 a 3-foot-deep blanket of snow lay on the ground, further lulling townspeople into a sense of security. Surely such deep snow would impede the progress of any attacking force, or at least slow them to the point the alarm could be sounded in plenty of time to establish a solid defense. Furthermore, 20 militiamen had arrived just four days ago. So, the townspeople slept on.

Two hours before dawn Lieutenant Hertel listened with eagerness to the hushed reports of his scouts. Snow had drifted up against the 10-foot-high northern wall of the Deerfield stockade. Nimble men on snowshoes should be able to scamper up over the wall and drop down into the village. Once inside, the advance party could open the gates for the attacking force.

Hertel ordered his men to advance to concealed positions just outside the stockade. Rather than approach en masse, small squads rushed forward for short distances to mimic the sound of wind gusts. Once the entire force was in position, they awaited their opportunity to strike. The only complication was a lone militiaman on night watch, keeping a listless patrol inside the stockade.

The militiamen had undoubtedly taken turns at watch, patrolling the perimeter through the long winter’s night, trudging through the snow and lugging their heavy muskets up and down the watchtower ladders. Like most colonial militiamen, they were probably poor, unskilled young men offered up by neighboring towns to fill the militia levy.

Perhaps they assumed no raiding party of any size could advance quickly and quietly through the deep snow. Perhaps they thought the reinforced palisade would thwart any invaders from entering the village. Perhaps, like the sleeping townspeople, they were wrong.

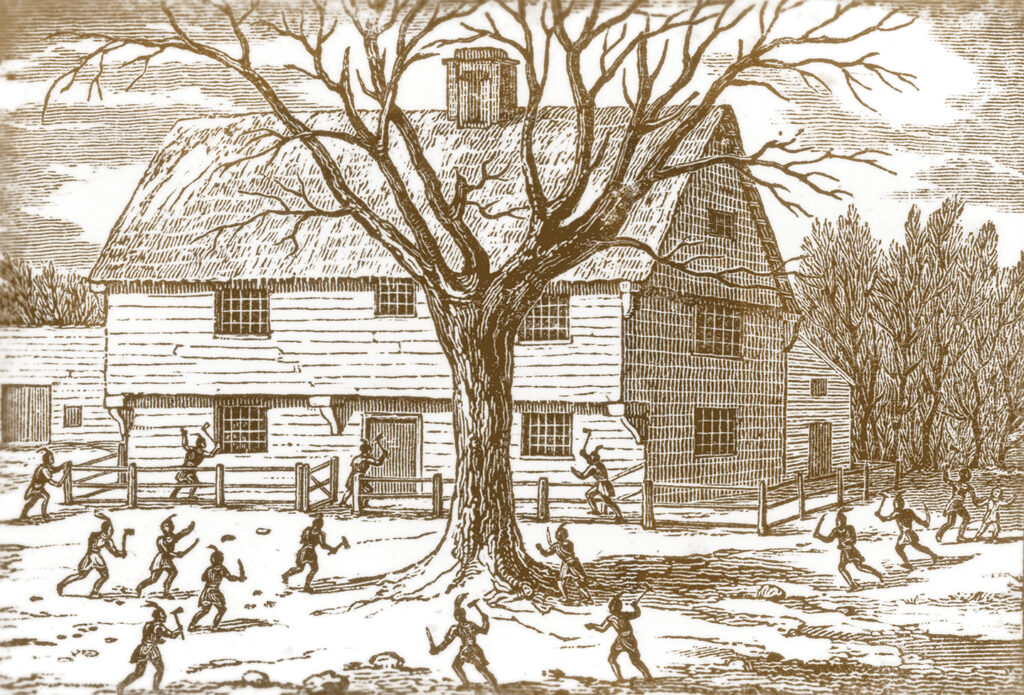

Lieutenant Hertel squinted in the predawn gloom as he scanned the north side of the stockade. Suddenly, a gap opened amid the timbers, and he cautiously led his force forward through the north gate of the stockade. The first phase of his plan had gone perfectly. Several chosen men had silently crept up the snowdrifts against the north wall and dropped down into the village. Undetected, they had swung open the gate’s heavy doors for their waiting comrades.

The next phase, a standard procedure for French-led raids, was to array small squads around each house. Once all squads were positioned, the attacks would commence simultaneously, thus attaining total surprise, minimizing resistance and limiting one’s own casualties.

But something went wrong. While Hertel’s raiders were still pouring through the north gate, a musket shot rang out, probably fired by the late-reacting sentry. Chaos erupted as mixed bands of French, Mohawks, Abenakis and Hurons fanned out through the sleeping village.

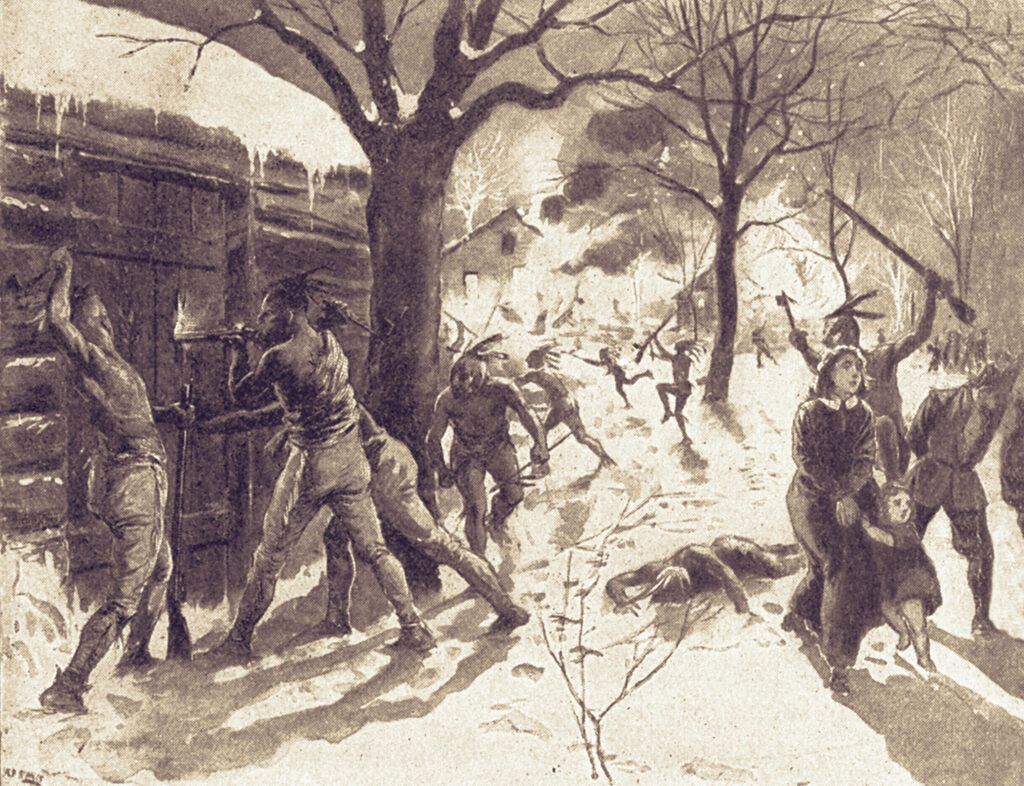

The Rev. Williams leaped from his bed at the commotion and hurriedly retrieved and cocked his flintlock pistol. As a clutch of warriors burst into his bedroom, he pointed its muzzle at the leading Abenaki and pulled the trigger. The resulting harmless click of a misfire probably saved the reverend’s life. Had Williams shot the Abenaki, follow-on warriors would almost certainly have slain him on the spot. Things were bad enough.

His assailants overpowered the reverend and bound his hands. Meanwhile, elsewhere in the house warriors murdered his 6-year-old son, John, and smashed 6-week-old Jerusha’s head against a doorway, killing her. Parthena, the Williams’ female slave, was also killed, likely defending the children.

One of the militiaman quartered in the house, garrison commander Lieutenant John Stoddard, jumped from an upstairs window, the deep snow breaking his fall. Clad only in his nightshirt and a cloak, he bound his feet with strips of cloth and ran through the snow to raise the alarm in the village of Hatfield, nearly 12 miles away.

The remaining occupants of the house—Eunice Williams, her surviving five children, Frank the slave and the other militiaman—were ordered to dress and ready themselves for the northbound trek into captivity.

Gunshots, war whoops and screams resounded through the village lanes and in homes where residents had quietly slumbered just moments before. Lieutenant Hertel must have been exasperated as he watched his plans evaporate into mayhem. All hope of command and control was gone.

Several townspeople, particularly those in the southern end of the village, fled in the direction of the nearby towns of Hatfield and Hadley. Some managed to shelter south of the village in the garrison house of Captain Jonathan Wells. Others burrowed into cellars and likely nooks to evade the attackers. Several of those in hiding survived the raid. Other unfortunates burned alive when their houses were set afire.

The raiders spread death and destruction throughout the village, indiscriminately killing babies and young children who would prove a burden to them on the return march to New France. They set torch to all structures in the village and slaughtered as many cows and sheep as they could while plundering food stocks and portable items of any value.

Entire families were rounded up and herded into the meetinghouse, which served as a holding area for captives. The raiders captured 112 residents of Deerfield and killed 50 others during the attack. But not all villagers were slain or taken without a fight.

Sergeant Benoni Stebbins had escaped from Indian captivity as a young man and resolved never to be captured again. Built for defense, the inner and outer walls of his house were filled with “nogging”—unfired bricks certain to stop musket balls. At the first sounds of the attack Stebbins had rushed to secure his home, which sheltered seven men, five women and several children. The well-armed defenders were determined to hold out as long as possible.

Hertel sent wave after wave of attackers in a costly effort to either overwhelm Stebbins’ outpost or set it afire. It would have proved smarter to bypass it. A Huron chief, an Abenaki captain and Ensign François-Marie Margane de Batilly were among the raiders killed or mortally wounded during the assaults. Hertel himself was wounded while leading one of the attacks, though the wound didn’t appear serious. At one point the French offered the defenders terms of surrender, but Stebbins would have none of it. After a firefight of more than two and a half hours, the raiders finally broke off the attack, but only after they’d wounded one of the women and a militiaman and killed the valiant Sergeant Stebbins.

As the first rays of dawn shone through the thick smoke, small groups of attackers made their way back toward the meadow where they had gathered the night before. Their progress was slowed by the plunder they carried and the bound prisoners who stumbled through the snow, choking on acrid smoke and their bitter tears. Behind them lay the blood trails of slain villagers and butchered farm animals, as well as the smoldering remains of their homes and everything they owned.

Lieutenant Hertel, anticipating counterattackers would not be far behind, sternly ordered his men to hurry. The chastened raiders in turn brandished hatchets and threatened their weeping captives to pick up their pace or face a quick death. Not all raiders heeded their commander’s warnings, however. Some lagged behind in the greedy search for further plunder or drunken bloodlust as they searched the ruins for more victims.

By early morning a force of armed New Englanders, alerted to the attack on Deerfield, rode to its relief from villages to the south. The force gained strength along the way, adding to their number soldiers who had taken refuge in Captain Wells’ fortified home. Other militiamen who’d fled the attack joined the group of 30-odd avenging New Englanders as they approached the charred village and engaged in a chaotic running fight with the last of the straggling raiders. Faced with the fury of the enraged militiamen, the attackers dropped their plunder and fled north.

Hertel knew from experience the New Englanders would follow. He also realized that his force, strung out and burdened by captives and plunder, would never be able to outrun pursuers hellbent on vengeance. But the experienced officer also understood that emotionally charged counterattackers were likely to act in haste, without proper reconnaissance. So, he rallied 30 reliable men and concealed them along a riverbank with clear fields of fire.

The New England relief force, having chased the last of the raiders out of the village, soon gained a true understanding of the wanton carnage resulting from the attack. Giving vent to anger and rage, some militiamen threw aside their coats and cumbersome equipment and ran in pursuit of the French and their allied warriors. Cooler heads, like Captain Wells, tried to establish command and control, but to no avail.

As the infuriated New Englanders ran headlong toward the river, Hertel sprang his trap. The concealed raiders opened fire, killing nine counterattackers and wounding many more. Though the raiders also suffered casualties, they succeeded in driving the New Englanders back behind the Deerfield stockade.

By nightfall the next day nearly 250 soldiers and armed citizens from western Massachusetts and Connecticut had gathered amid the smoking rubble of Deerfield. Though many were anxious to begin the pursuit of the French and Indian raiders, their leaders convened a war council. As they weighed the merits of various courses of action, the weather warmed and rain began to fall. Those with prior military experience realized the deep slush would slow progress to a crawl. Their plodding approach would in turn alert the raiders, who would probably massacre their captives. In the end, wiser voices prevailed, and the counterattack was called off.

The New Englanders returned to their homes harboring grief and hatred while the raiders and their captives slogged north through the snow.

The long and torturous journey to New France was marked by atrocities, including the drunken murder of Frank, the Williams’ slave, and the heartless killing of Eunice Williams, who was unable to keep pace because she’d recently given birth. A few Englishmen escaped, but warriors killed all those who fell behind. Of the original 112 captives, 89 survived the trek. Firsthand accounts also record small acts of humanity, like the strong words and actions of Huron warrior Thaovenhosen as he implored fellow tribesmen to spare captives from torture and mutilation.

On his triumphant return Lieutenant Hertel received widespread praise for the success of the Deerfield raid. While he led other raids and held additional commands, nothing compared to the devastating impact of the 1704 attack. Hertel was eventually promoted to captain, founded and served as commandant of Fort Dauphin (present-day Englishtown, Nova Scotia) and was decorated with the prestigious Ordre de Saint-Louis. The Hertel family finally received its patent of nobility in 1716.

The fate of the surviving Deerfield captives varied considerably once they reached Montreal and environs. Two men were worked and starved to death by their Abenaki captors. Most townspeople, however, were ransomed by French Canadian citizens, who treated them with compassion and humanity. Though not compelled by force to remain in New France, those who did stay were strongly encouraged to embrace Roman Catholicism. Some captives were adopted as full members of warriors’ tribes. Of the captives who survived the trek, some 60 eventually returned to New England. Many others married and began families, choosing to remain in New France the rest of their lives.

The Rev. Williams and four of his children were among those who returned home, in 1706. By then his 10-year-old daughter, Eunice, had been adopted by the Mohawks. She later married a Mohawk and bore their children in New France. Though she visited her New England relatives on several occasions, she and her growing family made their home in Kahnawake, a Mohawk community on the St. Lawrence River opposite Montreal.

Such happy endings aside, the Deerfield raid had been an act of terrorism, intended to strike fear into a target population through brutal violence, indiscriminate destruction and random victimization of noncombatants. Like many such terrorist acts, the raid was successful in the short term, as the fear of further French and Indian attacks discouraged English settlement in northern New England, if only temporarily. The raid also prompted overreaction against New England tribes as the English launched their own savage, punitive raids.

In the end, however, the policy of terrorism initiated by the French Crown only served to inflame England and her colonists and prompt acts of retribution, like the sorrowful expulsion of French Canadians from Acadia a half century later. Ultimately, the bitter harvest reaped at Deerfield contributed to the final defeat of New France in the 1754–63 French and Indian War.

Retired Brig. Gen. P.G. Smith, a former commander of the Massachusetts Army National Guard, teaches counter-terrorism strategy at Nichols College in Dudley, Mass. For further reading he recommends Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield and Captive Histories: English, French and Native Narratives of the 1704 Deerfield Raid, both by Evan Haefeli and Kevin Sweeney, as well as The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America, by John Demos.

This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.