The Philippine Sea: Just After Midnight, Monday, July 30, 1945

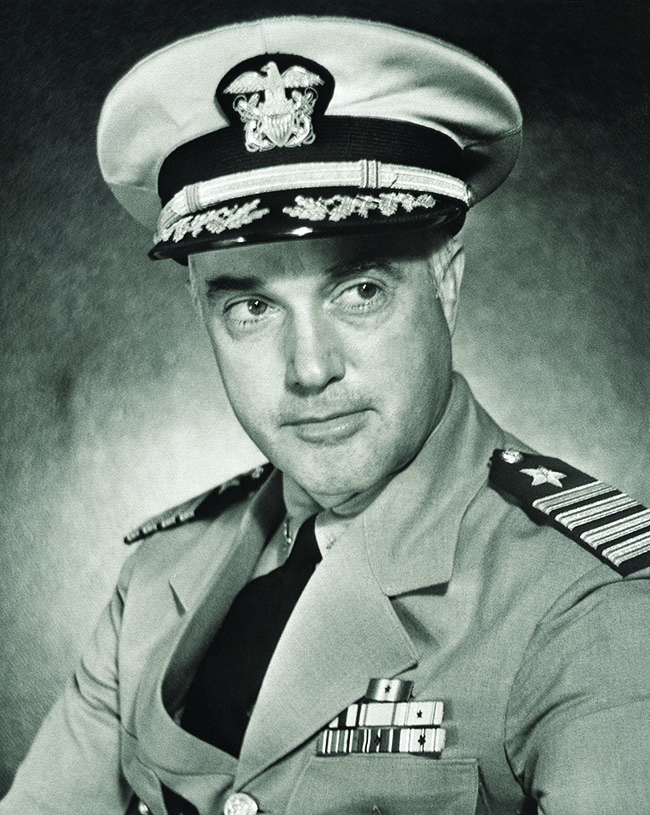

THE FIRST TORPEDO slammed into the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis’s starboard bow, killing dozens of men in an instant. The violent explosion ejected Captain Charles B. McVay III, 47, from his bunk in the emergency cabin just aft of the bridge. The ship whipped beneath him and set up a rattling vibration that took him back to Okinawa four months earlier.

Had they been hit by another suicider?

No, McVay thought. Impossible.

Another shattering concussion rocked Indy amidships. Acrid white smoke immediately filled McVay’s cabin. He picked himself up off the deck, felt his way to the cabin door, swung around the bulkhead, and appeared on the lightless bridge, stark naked. At that moment, there were 13 men on the bridge; only three would survive. For the captain and many others, a nightmare that would span decades was just beginning.

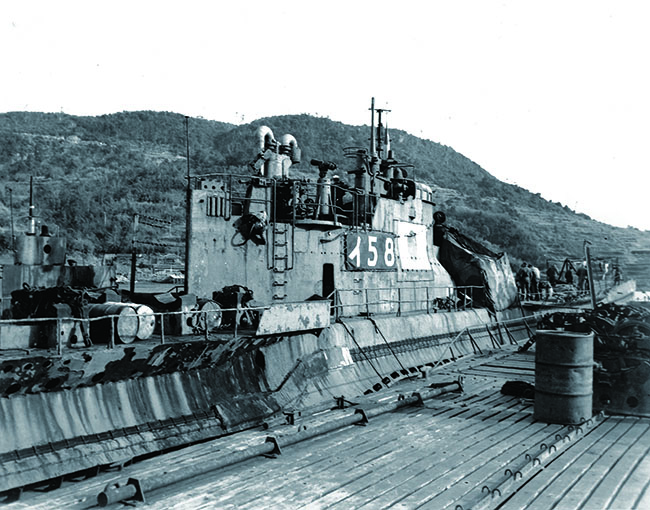

Fifteen hundred yards from Indianapolis, aboard the Imperial Japanese submarine I-58, Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto peered through his night periscope at the scene of destruction unfolding quickly before him.

“A hit! A hit!” he shouted. His elated crew improvised a victory dance.

To ensure he struck the American cruiser even if it had zigzagged—a maneuver for evading torpedoes the ship was almost sure to make—Hashimoto had fired six Type 95 oxygen torpedoes in a fanwise spread. His tactic had worked. Now, on the target’s main and after-turrets, skyscrapers of silver water shot toward the moon. Red tongues of flame followed immediately after, tasting the night.

Hashimoto had watched the enemy send many of his fellow submarine commanders down to salty underwater graves and feared that he would fail to take a prize for Japan before the war was lost. Filled with joy, Hashimoto prepared to send a message to his commander in chief: I-58 had torpedoed a large American warship.

Facing Death

Aboard Indianapolis, Captain McVay was trying to verify that a distress signal had been transmitted when a wall of water swept him from the ship along with hundreds of his men. From the sea, they saw the flagship of the Pacific Fleet standing on end, its stern towering over them. McVay and his men stared spellbound as Indy’s massive screws kept up a lazy turning, while all around them the phosphorescent water glowed like green fire.

Only 12 minutes had passed since the torpedo blasts. Now, amid a roar like waves pounding the beach in a storm, Indianapolis plunged straight down. McVay looked up to see men still leaping from the stern and the giant silhouettes of Indy’s port screws falling directly toward his head. As he pivoted and began to swim, hot fuel oil slid up the back of his neck, and soon he heard a loud churning sound behind him. When McVay looked again, his ship was gone.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Of the 1,195 men aboard Indianapolis, some 300 had gone down with the ship, including McVay’s executive officer, Commander Joseph Flynn, and the ship’s dentist, Lieutenant Commander Earl Henry Sr., whose wife had just had a baby boy. Now in the ink-black center of the Philippine Sea, 280 miles from the nearest land, McVay swiveled his head in the liquid darkness. He could hear men calling out as he floated alone in a thick layer of fuel oil, which rocked on the surface in a gooey slab, its tarry stench climbing down his throat like the caustic fumes of road construction. McVay found a pair of emergency rafts and soon after heard his quartermaster, Vince Allard, calling out in the dark. The last time McVay had seen Quartermaster Third Class Vincent Allard was on the deck, when Allard logged the captain’s order to cease zigzagging and return the ship to base course. Allard was struggling to support two young sailors who were in such bad shape that McVay thought they were dead. Both men, in fact, survived.

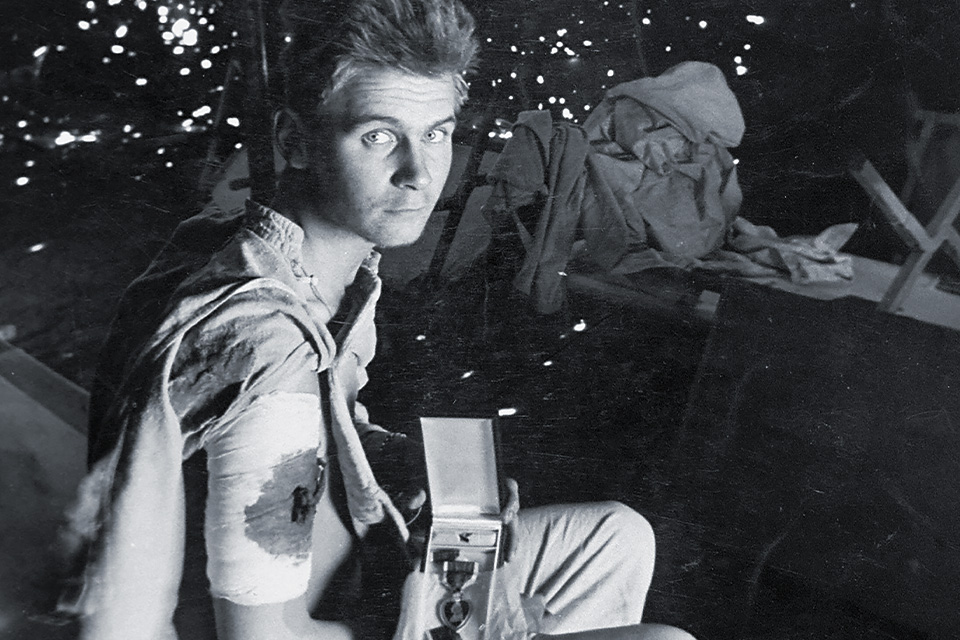

North of McVay’s position and far out of sight, Seaman Second Class L. D. Cox swam into another young sailor, Seaman Second Class Clifford Josey, who was covered in flash burns. In the dim moonlight, it looked to Cox as if Josey’s face was melting off. Cox stayed with Josey, held him, and soothed him with talk about what it was going to be like when they both got home to Texas. Within an hour, Josey was dead.

Over the next five nights and four days, many such quiet heroics—along with acts of cruelty and cowardice—would spin out across the survivor groups. Roughly 300 of the 880 men in the ocean coalesced into a single large mass. Some of these men only had life jackets; others, nothing at all. Other survivors were fortunate enough to find floater nets and rafts equipped with meager rations, flares, fishing supplies, and flashlights.

HOurs Become Days

At first, the men held out hope for rescue. But hours turned into days because the navy did not even realize the ship was missing. After delivering components to Tinian for the atomic bomb to be dropped on Hiroshima, Indianapolis regrouped at the nearby base at Guam before departing for Leyte, Philippines—an 1,100-mile straight shot across the Philippine Sea. Afterward, officers at Guam had done nothing other than move Indy westward on a plotting board according to her planned speed of advance—this despite confirmed reports of an enemy sub chase dead ahead of the heavy cruiser’s track. At Leyte, meanwhile, when Indy’s estimated time of arrival came and went, naval personnel noticed her absence, but also did nothing. Furthermore, intelligence personnel had intercepted the message Hashimoto sent about sinking a large warship and had transmitted it to high-ranking officers at Guam and Pearl Harbor, along with intelligence officers working for Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. The message was missing the location and type of ship sunk, but previous intel had placed Hashimoto’s boat, I-58, in the same area where Indy and her men were known to be. Again, no one took action.

As the days passed, hundreds of men died of their wounds or gave up hope and drowned themselves. Many sailors were taken by sharks. One moment, these predators behaved like gentle and curious giants, nosing up close to inspect the men with black, unblinking eyes. The next, they attacked, their steel-trap jaws snuffing out a man’s life before he could draw a breath to scream.

✯✯✯✯✯

Recommended for you

Over the Philippine Sea: Aug. 2, 1945

By the morning of Thursday, August 2, the men had been in the water for four nights and three days. Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn, a navy pilot, was flying over the Philippine Sea in his Lockheed PV-1 Ventura bomber. It was just after 11 a.m., and Gwinn was 350 miles north of Palau, cruising at 3,000 feet. At this altitude, he could see 20 square miles at a glance, and the sea below appeared as smooth and reflective as a foil sheet.

His crew was testing a new trailing antenna that had become tangled for the third time. Frustrated, Gwinn turned the controls over to his copilot and ducked into the Ventura’s belly to help. Gwinn bent to take a look through a window in the deck—and almost as quickly leapt to his feet and dashed for the cockpit.

“What’s the matter?” his aviation ordnanceman shouted over the propeller noise.

Gwinn shouted back, “Look down and you’ll see!”

He had spotted an oil slick, which he took for the telltale trail of an enemy submarine. When he descended for his attack run, though, Gwinn saw the last the thing he expected—people.

The pilot alerted his squadron commander at Peleliu, who dispatched a PBY-5A Catalina, or “Dumbo,” with Lieutenant Adrian Marks at the controls. When Marks reached the survivors, he saw that many would not last until a ship could arrive to fish them out of the sea. Then his crew saw a shark take another man; Marks, against regulations, decided to make an open-sea landing.

Shortly after 5 p.m., against a lowering sun, Marks executed a power stall into the wind and slammed his airplane belly-first into the back of a huge swell. The Dumbo’s hull screeched in fury, emitting all the sounds of a crash. The crew pitched forward, safety harnesses crushing their chests. The sea rejected the plane, batting it 15 feet back into the air. Fighting physics, Marks gripped the control column with both hands. The Dumbo’s belly again smashed into a wave and again bounced—but not as high this time. Marks wrestled the controls, willing the plane to obey. Finally, the Dumbo breached the swell’s shining skin.

Marks and his crew saved 53 men. Near midnight of the men’s fifth night in the water, rescue ships finally arrived and hauled aboard 263 more, though men continued to die even after rescue operations began. The ships transported survivors to base hospitals around the Philippine Sea before eventually bringing them all to Guam. While the navy encouraged the men to write letters home, it prohibited them from mentioning their whereabouts, the fact that Indianapolis had sunk, their nurses or doctors, or to refer in any way to the ordeal they had just survived.

✯✯✯✯✯

Mayfield, Kentucky: Aug. 13, 1945

Eleven days had passed since the rescue when Jane Henry, the wife of Indianapolis’s dentist, hurried to the upstairs phone to answer it before the ringing woke up the baby. Jane and two-month-old Little Earl were staying with her parents, George and Bessie Covington. In his last letter, Earl Sr. had gushed about the photos of the son he had yet to meet. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, he wrote, if the war was over by the time Indianapolis returned to the States?

Jane snatched up the phone and heard voices already on the extension.

“George, we are so sorry to hear the news.”

“What news?” Jane heard her father say.

The other voice paused. “Horace and Arletta just got a telegram today from the navy,” he said, referring to Earl’s parents. “It says Earl’s missing in action.”

Jane’s insides went cold. She raised a hand to brace herself against the wall.

The next day, Jane received her own version of the dreaded telegram, which she read through a curtain of tears:

I DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU THAT YOUR HUSBAND, EARL O’DELL HENRY, LIEUTENANT COMMANDER USNR, IS MISSING IN ACTION 30 JULY 1945 IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY. YOUR GREAT ANXIETY IS APPRECIATED AND YOU WILL BE FURNISHED WITH DETAILS WHEN RECEIVED.

Later that morning, a town church bell began ringing, its insistent peal floating down the street in joyous song. Another bell joined, and another, until it seemed every church tower in Mayfield had joined in some kind of rapturous chorus. George opened the door to see people spilling out of their homes, laughing and crying and embracing. Even inside the house, Jane could hear their words: “Japan surrendered! The war is over!” She looked down at the wrinkled telegram still clutched in her hand and wept.

✯✯✯✯✯

Washington Navy Yard: Dec. 3, 1945

Four months after being pulled from the sea, Captain Charles McVay walked into the courtroom in Building 57 at Washington Navy Yard.

A week-long naval court of inquiry had recommended that McVay be tried by court-martial, the primary charge being he had endangered his ship by failing to zigzag— despite the fact that, with no known submarine threat, it was standard procedure to cease zigzagging at night when visibility was poor. On September 25, Admiral Ernest King concurred. King also ordered what would come to be called a “supplemental investigation.” This probe roved far and deep, and the officers conducting it did not hesitate to report facts that might expose the navy’s failures in Indy’s sinking. These men sent regular updates to King. One of these updates may have sealed McVay’s doom.

On November 9, King’s inspector general, Admiral Charles Snyder, said McVay felt the new investigation might produce evidence favorable to his case and suggested the court-martial be delayed until that investigation was complete. That would be sometime in mid-December. King first agreed to the delay, but quickly reversed himself after learning that the men conducting the investigation wished to interrogate the leading lights of the Pacific War—including admirals so senior they had personally accepted the Japanese surrender. On November 12, King ordered the court-martial to proceed at once. In doing so, he would ensure that the admirals’ testimony—and accounts of the navy’s inaction—would not reach the public ear.

✯✯✯✯✯

Washington, DC: Dec. 10, 1945

Sub commander Mochitsura Hashimoto stood atop a run of aircraft loading stairs and looked out at a foreign land: Washington, DC. The victor had summoned the vanquished: the U.S. Navy had called Hashimoto to testify at McVay’s court-martial. Already, a procession of witnesses had testified about such topics as visibility, moonlight, abandoning ship, and whether the Indianapolis crew knew of the protracted submarine chase ahead of its track, while reporters scribbled furiously. But when Hashimoto arrived, American newspapers began calling him a “star witness.”

McVay’s attorney and his supporters ob-jected vigorously to an enemy commander testifying against an American officer. But Hashimoto ended up testifying that zigzagging would not have saved Indianapolis. Or he tried to: fatefully, an interpreter mistranslated his words, giving the opposite impression.

Defense witness Captain Glynn Robert Donaho, a 15-year submarine veteran, did testify, initially, that zigzagging would not save a target from a torpedo strike. With this, momentum seemed to have swung in McVay’s favor. But after enduring more than 50 sometimes-condescending questions from prosecutor Captain Thomas J. Ryan, Donaho undercut all he had said by admitting that when a target ship zigzags, it can be “disconcerting” for a submarine commander, as it throws off his calculations.

With that, a wrecking ball smashed into the defense. The military court found McVay guilty of hazarding Indy by failing to zigzag. He was sentenced to lose 200 numbers toward his advancement to commodore—meaning 200 men of McVay’s rank would move ahead of him for promotion—with a recommendation for clemency.

McVay knew his career was over and carried his fate with stoic resignation. But grief did not fade for the families of the lost, and many undertook a campaign to never let McVay forget it. While their son or brother or father or husband had disappeared into the deep, McVay, in their view, had received a slap on the wrist and a lifetime pension.

For 23 years, letters from the families of those lost, like the Joseys and the Flynns, arrived in his mailbox in envelopes that seemed sealed with venom.

If it weren’t for you, my son would be 25 years old today!

If it weren’t for you, I’d be celebrating Christmas with my husband!

If it weren’t for you, my girls would have a father!

At first these rants came weekly. Then they tapered down and came mainly around Christmas and other milestone dates. But they never stopped.

McVay bore silently the torture of those 879 Indianapolis deaths, his sense of guilt and grief swelling in that eternal river of hateful letters. Finally, it was too much. On November 6, 1968, he dressed in his usual navy uniform of a pressed khaki shirt and matching pants. At 12:30 p.m., he walked out the front door of his home in Litchfield, Connecticut, sat down on a stone step, put a .38 revolver to his temple, and pulled the trigger.

McVay was not the only Indianapolis survivor to end his own life. At least a dozen more committed suicide within a few years after the sinking. Even among those who lived, no man who went into the water came out the same.

✯✯✯✯✯

Offices of Sen. Bob Smith: June 1999

When salvation came, it came 31 years later, and from an improbable source.

“Look, Bob, I respect you, I’m on the committee with you, but come on,” Senator John Warner of Virginia was saying. “This is some kid’s school project. Is this really worth a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee?”

Warner’s response was typical of the uphill battle New Hampshire senator Bob Smith had been fighting for a year. That’s how long it had been since he had first spied a line item on his daily agenda that stopped him cold.

“What’s this?” Smith had said, shooting a quizzical look at his legislative assistant, John Luddy. “‘USS Indianapolis and Hunter Scott?’”

“It’s a meeting with the survivors of USS Indianapolis, sir,” Luddy said.

“Hunter Scott is an eighth grader,” Luddy added. “He’s a constituent of Joe Scarborough,” a congressman representing Florida’s 1st Congressional District.

From all the material the 14-year-old had collected, one theme emerged. To a man, the survivors were still outraged over the treatment of their captain. Hunter Scott rallied to their cause.

Also outraged was U.S. Navy Commander Bill Toti, the last captain of a nuclear attack submarine—also named USS Indianapolis—decommissioned the year before. Having extensively studied the navy’s position, Toti found their treatment of the captain offensive. At the Pentagon, he worked tirelessly on the survivors’ behalf. He published a new analysis of McVay’s role in the Indy disaster in the prestigious journal, Proceedings. As both a friend to the survivors and an aide to the vice chief of naval operations, Toti found himself uniquely positioned to influence the navy’s final word on McVay’s culpability for the disaster.

To secure the Senate hearing, there was only one man Smith needed to convince: Warner, the committee chair. But Warner was opposed to reopening the issue.

“The navy’s already decided this,” Warner said. “We’re going to stir up a hornet’s nest that doesn’t need to be stirred up.”

“We’re going to listen,” Smith said. “That’s all we’re going to do. Exoneration comes later, if you agree with it. If you don’t agree with it, we won’t do it.”

After months of wrangling, Smith finally secured his hearing.

✯✯✯✯✯

Senate Armed Services Committee: Sept. 14, 1999

Three months later Senator Warner brought the hearing to order. He praised the courage of the men aboard Indianapolis “that fateful night” 54 years earlier, particularly those survivors present in the hearing room.

Among the witnesses were the young Hunter Scott; survivor Paul Murphy, who argued that the navy had blamed McVay to avoid admitting its own mistakes; and journalist Dan Kurzman, who spotlighted his discovery of a “smoking gun.” Kurzman had found a memorandum buried deep in the National Archives. From the former special assistant to the navy secretary in 1945, it read: “The causal nexus between the failure to zigzag and the loss of the ship appears not to have a solid foundation.”

In the end, however, the man who finally persuaded Warner was the same one who sank Indianapolis. In November 1999 Japanese commander Mochitsura Hashimoto of submarine I-58, then 90 years old, wrote a letter to the senator expressing his dismay over the fact that McVay was ever tried in court:

I HAVE MET MANY OF YOUR BRAVE MEN WHO SURVIVED THE SINKING OF INDIANAPOLIS. I WOULD LIKE TO JOIN THEM IN URGING THAT YOUR NATIONAL LEGISLATURE CLEAR THE CAPTAIN’S NAME. OUR PEOPLES HAVE FORGIVEN EACH OTHER FOR THAT TERRIBLE WAR AND ITS CONSEQUENCES. PERHAPS IT IS TIME YOUR PEOPLES FORGAVE CAPTAIN MCVAY FOR THE HUMILIATION OF HIS UNJUST CONVICTION.

For Warner, it was the final weight on the scale. He decided to take the exoneration resolution to the Senate floor. On October 12, 2000, the measure passed.

House Joint Resolution 48 also passed, and with stronger exoneration language: that the “American people should now recognize Captain McVay’s lack of culpability for the tragic loss of USS Indianapolis and the lives of the men who died as a result of the sinking of that vessel”; and that “Captain McVay’s military record should now reflect that he is exonerated for the loss of USS Indianapolis and so many of her crew.”

Finally, Captain Charles McVay’s record reflected his innocence.

✯✯✯✯✯

The Philippine Sea: Aug. 19, 2017

But Indy’s story still had one final chapter. In 2017—17 years after McVay’s exoneration—a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, whirred across the seafloor 18,000 feet down. Its camera resolved an object that had been shrouded in darkness for 72 years. The number 35 popped out of the inky black, as crisp as the day it was painted.

“That’s it, Paul, we’ve got it. The Indy!”

“Paul” is Microsoft cofounder Paul G. Allen, whose team had found what many argue is the most important American military shipwreck to be discovered in a generation: USS Indianapolis.

Calls rang out across the country to survivors and family members of those lost at sea. Their reactions, although varied, had the same tone—amazement followed by reverence. For Earl Henry Jr., the 72-year-old son of lost-at-sea dentist Lieutenant Commander Earl Henry Sr., emotions unexpectedly broke through. After a lifetime of uncertain longing, he finally knew where his father was.

Back in the Philippine Sea, after many dives to the wreck, the ROV’s thrusters rotate it away from the wreck for the last time. Recalled to its mothership on the surface, the vehicle takes its host of lights, camera, and sensors with it. Once again, darkness envelops the ship’s proud lines. Leaning just slightly to starboard, it’s as if the ship is cresting a wave, shrugging off another swell on her way to an important mission. Guns trained toward the sky, Indianapolis is ready for all who might challenge her, forever on patrol. ✯

Adapted from INDIANAPOLIS by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic. Copyright © 2018 by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.