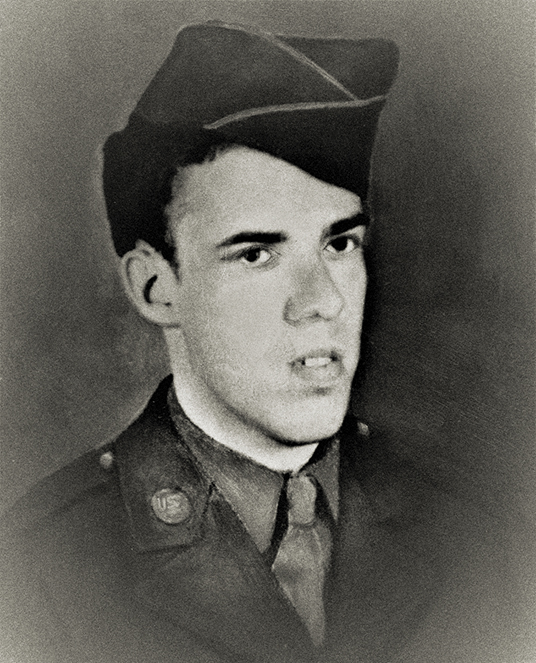

My brother, Private Joseph Patrick Donnelly, was a member of the 9th Armored Division, 19th Tank Battalion, Headquarters Company. He was killed on November 10, 1944, in Scheidgen, Luxembourg, and is buried in Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery and Memorial in Belgium. Unfortunately, most of Joe’s military records were destroyed in the 1973 St. Louis Archives fire. What can you tell us about Joe and his unit? —Rich Donnelly, Williamstown, New Jersey

The lineage of your brother’s unit, the 19th Tank Battalion, goes back to 1836 and the formation of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment. The 2nd Cavalry saw action in some of the most notable campaigns in U.S. military history, including Gettysburg, Little Big Horn, and the Meuse-Argonne (as America’s only horse-mounted cavalry unit to fight in World War I).

The week after the Pearl Harbor attack, the regiment was sent to Arizona to guard military installations before being assigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, in July 1942. There, the 2nd’s century-old service as a cavalry regiment came to an end and it was redesignated the 2nd Armored Regiment, part of the 9th Armored Division, with its men transitioning from horses to tanks. The 2nd Armored Regiment comprised the 1st Battalion (light tanks), the 2nd and 3rd Battalions (medium tanks), and a Provisional Battalion, which included Headquarters Company.

The newly formed 2nd Armored Regiment trained at Fort Riley until June 1943. Your brother enlisted in the army on November 12, 1942, so he joined the regiment there. While Headquarters Companies like your brother’s were most often responsible for the overall administrative maintenance of a regiment, they often included recon and mortar platoons. It’s likely your brother was assigned to one of the latter.

In June 1943 the 9th Armored Division headed west for desert maneuvers in, as the unit history described it, “brain-broiling heat” near Needles, California. On October 9, 1943, the 3rd Battalion was redesignated the 19th Tank Battalion and, in November 1943, moved with the rest of the 9th Armored Division to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for nine months of maneuvers, training, and testing before deploying overseas.

On August 20, 1944, the 9th sailed from New York to Scotland’s west coast before taking a train south into England to be billeted at Tidworth Barracks, only a few miles from Stonehenge. Assigned to the U.S. Ninth Army, the 9th was the first armored division to receive the latest model Sherman M4A3s—with 76mm guns and 500-hp V-8 engines—and new 105mm howitzer assault guns. With these tools in hand, they sailed from England on October 1, 1944, and landed in France two days later. The troops stayed in Ste.-Marie-du-Mont, Normandy, for ten days while prepping to march east, and the unit history evokes the details of what might have been your brother’s experience: “Nightly movies and broadcasts of the 1944 World Series helped to while away the chilly, rainy days.”

On October 13, the push toward Germany began. The 9th covered 475 miles in six days, arriving in central Luxembourg, an active combat zone, on October 19. For two weeks the division remained in reserve, during which time it transferred from the U.S. Ninth to the First Army. On November 3, the 19th Tank Battalion moved to the front at Scheidgen, Luxembourg, an evacuated town, where it shelled German positions in its first wartime action. On November 10, the 19th took its first casualties. An assault gun platoon moved under cover of fog into firing position. When the fog suddenly lifted and exposed the platoon, a barrage of German artillery found its mark. All six tanks in the platoon were hit, killing three men and injuring six. This is no doubt the battle in which your brother lost his life.

The 9th Armored Division soon found itself at the forefront of the Battle of the Bulge, meeting the initial German thrust on December 16. The 19th Tank Battalion was assigned near Echternach, Luxembourg, with some elements of the battalion farmed out to support other units. On January 3, 1945, after months of intense fighting and 125 battalion casualties during its advance east, the 19th was relieved and its role in the Bulge ended. Fifteen battalion officers and men later received decorations for their actions.

The 19th rejoined the fight in late February 1945 as the U.S. Army advanced across western Germany and headed east toward the Rhine. During this campaign, the 19th split up into company-size groups attached to various infantry units. On March 24, the battalion crossed the Rhine on a pontoon bridge at Remagen, near the site of the famed bridge that had been taken by other elements of the 9th Armored Division on March 7, but which had collapsed on March 17 after repeated German sabotage and bombings.

On April 8 the battalion received orders to drive about 150 miles toward the Elbe River, near Leipzig. Fighting intensified throughout April in the last-ditch German attempt to stave off defeat. Town-by-town battles against anti-tank guns, sniper fire, mortars, and artillery from retreating Wehrmacht troops resulted in heavy American casualties, but by early May the end of the war was clearly at hand. The unit history recalls the subdued mood when Germany surrendered on May 8: “As in most combat units, the news came to the 19th Tank Battalion as no surprise and was taken with little excitement.… Despite the lack of wild celebration there was a definite feeling of relaxation…and everyone began to realize just how great the strain had been.”

The 19th then assumed occupation duty. First stationed between Leipzig and Nuremberg, the battalion took on outpost duty to help control refugees fleeing west from the Soviets and to pick up any straggling German soldiers. Some battalion members guarded factories, hospitals, and POW work patrols, while others served in the newly established camps for displaced persons.

In October 1945, the 9th Armored Division returned to the United States, and the division was inactivated on October 13, its major role in the defeat of Germany complete. Your brother’s name, Joseph Patrick Donnelly, is listed in the unit history among the 52 members of the 19th Tank Battalion who died in those final months of World War II. Major General John W. Leonard, division commander, wrote in an official commendation letter to the 9th Armored Division after the Battle of the Bulge: “Let us not forget our gallant dead, and let each of us say a fervent and humble prayer that God will have mercy on their souls.”