[dropcap]H[/dropcap]istory little notes the final great confrontation in the West European theater, and not without reason. When supercharged American armies were encircling and—in an ironic echo of the Blitzkrieg—crushing the last Wehrmacht force there, Germany was scant weeks from unconditional surrender. Amid the war’s final tumult, peals of relief at Adolf Hitler’s downfall, and horrifying revelations about the Final Solution, it’s easy to overlook the Battle of the Ruhr Pocket, the climax in a tale of two armies.

The Wehrmacht had dominated the theater’s early years, but by 1945, German losses were soaring, replacements were not keeping up, and much of the Reich’s army consisted of Volkssturm (People’s Assault) units: old men and boys, sketchily trained and haphazardly equipped. German weapons—Tiger tanks and Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters—might have been quite advanced technologically, but they rarely made a difference to the men at the front. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, German supreme commander in the west, once complained that leading German armies in those days was like “playing a Beethoven sonata on an old, rickety, out of tune piano.”

As the Wehrmacht was descending, the U.S. Army was rising. The Americans stumbled in their North African and Italian debuts, but by 1945 had grown as seasoned and professional as any combatants in the field. Buttressed by weapons, fuel, ammunition, and food of lavish proportion and quality, the U.S. Army was mobile and lethal. Finding a seam in enemy defenses, an American unit could slash through and hurl more brute firepower than any force ever. The intensity of American artillery never ceased to shock the Germans, who had to obliterate more selectively. And overhead, American commanders had a literal thunderbolt: the Republic P-47, which, along with the Consolidated P-51 Mustang and other fighter-bombers, made it nearly impossible for German forces to move by day.

In 1945, all these advantages coalesced in an engagement of a rare sort. World War II was messy and unpredictable, and plans rarely worked out as conceived. In the Ruhr Pocket, however, the U.S. Army lived and fought the dream: establishing full-spectrum dominance to achieve, at minimal cost, the greatest American victory of the European war.

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]arly 1945 saw the Allies still trying to shake off the shock of the great German offensive in the Ardennes Forest. Even after they righted themselves and regained momentum, the going was slow, with a month of gritty fighting needed to clear the densely populated Rhineland and close on the great river itself. Allied armies were still 300 miles from Berlin, and final victory seemed a long way off for Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower’s four-and-a-half-million men: in the north, 21st Army Group, consisting of British, Canadian, and American forces under Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery; the all-American 12th Army Group in the center under General Omar Bradley; and in the south the 6th Army Group, American and French forces under General Jacob L. Devers.

The Rhine presented a dauntingly serious obstacle—until, in one of the war’s most dramatic moments, that watery barrier evaporated. On March 7, astonished Americans, seeing that the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen still stood, rushed the span just as German explosives failed to knock it down.

Suddenly, the Allies were over the Rhine. Within the hour, Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges was pushing every man and vehicle of his First Army that he could across the railroad bridge to form a powerful lodgment on the east bank.

Despite that lucky break, a Rhine crossing was only the means to an end. The task now was to smash the Wehrmacht and finish the war—easier said than accomplished. In the Americans’ path stood German Army Group B, with the 5th Panzer Army on the right and on the left the Fifteenth Army, a total of 400,000 men. The 5th Panzer was defending the Ruhr, one of the last remaining German industrial centers, home to the massive Krupp Steel Works at Essen. The Fifteenth Army opposed the U.S. bridgehead east of Remagen.

Army Group B’s commander, Field Marshal Walter Model, was one of the most determined fighters left in Hitler’s stable. A bitter-ender and highly skilled defensive specialist, Model was, in his men’s words, the “Führer’s fireman,” thrown in where the fighting was hottest and the straits most dire.

A mean Prussian with an acid tongue, Model was a gifted tactician. Son of a non-military middle-class family, he fought as a lieutenant in World War I, was badly wounded twice, and was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. On World War II’s Eastern Front he earned a reputation as a defensive genius, commanding the Ninth Army during the furious Soviet winter offensive of 1941–1942, holding the city of Rzhev while German armies around his were reeling back or dissolving, and reprising that feat during the massive 1943 Soviet thrust at Orel.

Model spurned complexity. He preferred to maintain a cohesive front, no matter how weak in spots, and backstop it with multiple fortified lines, husbanding his reserves until the Soviets committed to an attack, whereupon he plugged the holes with a brisk counteroffensive. This doctrine did not bring victory, but did ward off catastrophe often enough to make Model Hitler’s favorite commander.

Above all, Model was ruthless: toward his officers and men, toward the enemy, toward Soviet civilians unlucky enough to live in his zones of operation. During the Ninth Army’s 1943 retreat at Orel, he infamously evacuated the district’s entire population, with great loss of life. In 1944, hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens died in concentration camps behind his lines in Latvia. These deeds landed him on a Soviet list of war criminals. He even made Hitler uncomfortable. “I trust that man to make it happen,” the Führer declared, “but I wouldn’t want to serve under him.”

To get home, the Americans had to go through Model and Army Group B, whose armies were still strong enough to bloody an attacker foolish enough to launch a frontal assault. As the Soviets had learned, even weakened German forces usually had cohesion, experienced troops, and morale enough to gut a clumsy assailant. If German boys were willing to die hard in the Caucasus and in the Crimea, there was no reason to think they would fold on home soil.

Even before D-Day, the Allies had in mind to seize the Ruhr and paralyze German heavy industry. But a fight through the Ruhr, that sprawl of cities, factories, and millions of civilians, was the stuff of bloodbaths, promising urban warfare on an unimaginable scale. For that very reason, Eisenhower had always intended not to blast straight at German forces in the industrial area but to encircle them. Often maligned as a dull “broad front” strategist who preferred to keep his armies advancing in lockstep, Ike nonetheless knew a battlefield opening as well as any general in the war. And that lucky turn of the card at Remagen revealed an enormous one.

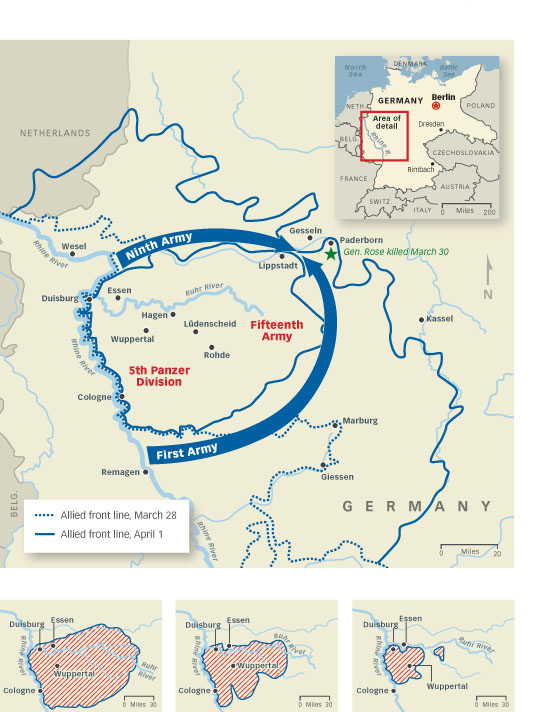

Eisenhower called for a classic two-army pincer maneuver. Hodges’s First Army would break out at Remagen and drive east. Meanwhile, 90 miles north, the U.S. Ninth Army under Lieutenant General William H. Simpson would traverse the Rhine at Wesel as part of Montgomery’s multi-army crossing, Operation Plunder. Once over the river, the Ninth, too, would motor east. Essentially, one American army would be on the Ruhr’s northern flank, and another on its southern. Each would wheel toward the other and link up, enveloping Army Group B.

The plan was fraught. As they advanced, the American armies would not be able to maintain contact. Success required the immobilization of German forces by denying them fuel and attacking from the air, along with surprise and speed—but mainly speed. Otherwise Model might spot the threat and deploy reserves, as he had done on the Eastern Front.

But Allied intelligence had drawn a detailed and accurate portrait of the German defense. In the south, Hodges would target German LXVII Corps, holding the left—southern—flank of the Fifteenth Army. Hard fighting in the Rhineland had left the corps understrength, undersupplied, and shy about reconnaissance patrolling, a sure sign of ebbing German élan. In the north, however, the U.S. Ninth Army would be moving more slowly, and Simpson’s forces were not yet over the Rhine. Montgomery, a by-the-numbers fellow, liked to square things away and take his time doing so. Moreover, the marshy, wooded terrain east of Wesel harbored a reserve Panzer division that Allied reconnaissance flights had just identified as the 116th. Characteristically, Montgomery decided to augment his crossing with an airborne drop, Operation Varsity, to disrupt defenders and keep German reserves from the front.

Montgomery launched Operation Plunder-Varsity on March 23 with a four-hour, 4,000-gun barrage preceding drops by British 6th and U.S. 17th Airborne Divisions.

The parachute troops experienced heavy losses, but the main body got over the Rhine against weak resistance, installing itself on the far bank. (See “Storm over the Rhine,” January/

February 2015.) Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army now prepared to break out to the east, with 8th Armored and 2nd Armored Divisions probing for German weaknesses.

As anticipated, the pace was plodding. The Ninth Army took a full week to chew through the enemy and the terrain, aided every step of the way by heavy artillery fire and nonstop air sorties. Even so, not until March 29 could Simpson break clear.

While the Ninth Army was shouldering ahead, the First Army at Remagen put on the one of the great American shows of the war. North to south, Hodges arrayed three corps abreast: VII Corps under Major General J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, III Corps under Major General James Van Fleet, and V Corps, led by Lieutenant General Clarence R. Huebner. Crowding 35 miles of the Rhine’s east bank, the corps bulged with manpower and equipment and the usual extravagant firepower.

The attack that began the Battle of the Ruhr Pocket opened before dawn on March 25 and simply vaporized the German defenders. Even the weather cooperated, offering a crystalline day; XIX Tactical Air Command owned the skies, swooping at will onto hapless Germans. By noon, all three American corps had departed the bridgehead, covering 12 miles that day and 20 the next. In the frenetic advance, infantrymen, rather than wait for trucks, often hitched rides on passing Shermans.

Already, American forces were taking the surrender of myriad Germans—17,000 by III Corps on March 26 alone. A few enemy units attempted counterattacks, but American momentum smothered those efforts before they got started, and most GIs probably never even noticed them.

Onward came the Americans, reaching Giessen and Marburg on March 28. Having advanced 80 miles, the First Army wheeled north. It was time to cut across Army Group B’s rear and link up with the Ninth Army to envelop the entire German force in the Ruhr—giving the enemy a taste of his trademark Kesselschlacht, or “battle of encirclement.”

Third Armored Division commander Major General Maurice Rose was an aggressive and hard-driving leader, considered by many the best tanker in the U.S. Army. Rose believed in attacking “even with insufficient strength and against superior numbers,” capitalizing on armor’s speed and power.

Assembling a task force—a reinforced tank battalion, including three of the army’s newest M26 Pershing tanks, under Lieutenant Colonel Walter B. Richardson—Rose now issued a simple order: “Just go like hell.”

The troops in the task force complied, loping forward with alacrity. Next morning, groggy tank crews finally met actual German resistance, an ad hoc battalion of SS cadets supported by armor. A tough, two-day scrap ensued. On March 30 General Rose came up to supervise. On the way to the front, his column—two jeeps, a motorcycle, and an armored car—encountered a company of Tiger tanks of the 507th Battalion. In that firefight, Rose was killed. But American forces kept coming, sidestepping SS defenses at Paderborn and heading west toward Lippstadt. As had become a given, the Germans were unable to keep up with their opponents.

Model and his staff spent most of their time trying to elude the rampaging foe. Rocked by the American rush, Model relocated Army Group B headquarters north from Rimbach to Rohde, then moved again, this time further north to Lüdenscheid, finally evacuating to Wuppertal: four headquarters in three weeks. This constant repositioning sapped valuable hours and energy, and forced Model into reactive mode. Chased from town to town to town, the Führer’s fireman could never pause long enough to douse the flames.

At Lippstadt, American lead elements—the Ninth Army coming over from Wesel, the First coming up from Remagen—made contact. Just after the noon hour on April 1, Easter Sunday, the pincers snapped shut, and the U.S. Army achieved its greatest encirclement of the war.

The Americans had trapped Model’s Army Group B—5th Panzer and Fifteenth Armies, seven corps, and 19 divisions, each accompanied by its support troops and headquarters—in an egg-shaped portion of the heavily developed Ruhr. The pocket, which roughly measured 30 miles by 75 miles, was studded with cities, towns, and factories. Within its precincts were 26 German generals and even an admiral, Werner Scheer, who commanded Defense District I in Essen.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Americans’ blistering tempo so shredded German command and communications that Model and cohort could barely respond. Since 1945, historians have composed litanies of explanations: half-strength divisions, scarce fuel, Allied air superiority, morale collapse, and of course, Hitler’s allergy to tactical retreat. Caught in a perfect equation of military disaster, Model did his best, trying to shift his meager reserves into the path of the American thrust and ordering counterattacks that died just as they were getting started. By April 2 Model had lost contact with the commander of his Fifteenth Army, General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen. Presumed captured or killed, Zangen was neither—however, he and Model could not make radio contact. Model appointed another commander and ordered him to launch a counterattack with units from the Fifteenth Army, just as Zangen was trying to form his stragglers into a new defensive position to the east. No wonder confusion gripped so many German soldiers.

To the Ruhr’s populace, the Americans seemed to arrive out of the blue. Near Paderborn, villagers at church in Gesseln on Tuesday, April 3, heard sprocket wheels squeaking, treads clanking, and engines roaring. As a woman was whispering to the celebrant, “Herr Vicar, they are here,” the muzzle of a Sherman’s 76mm gun poked through the church door, trained on the altar. GIs defused the moment by entering the nave, kneeling, and joining parishioners attending Mass.

The battle wrought enormous physical destruction. Since Easter, artillery units attached to U.S. XVI Corps northwest of the pocket had fired no fewer than 259,000 rounds. At that rate American gunners may well have fired one million shells during the battle. Factories closed. Production ceased. So did distribution of food in the region’s densely populated municipalities. Electricity, water, and sewer systems broke down—a recipe for epidemic. Russians and Poles unshackled from the Nazi slave empire pillaged at will. The merest gesture of resistance—a sniper’s shot, a random mortar round, a skirmish—enraged the “Amis,” who almost always replied with a storm of shelling that flattened the vicinity. German civilians could try to surrender early at the risk of retribution by Nazi diehards, or wait too long to do so, and chance experience with the American way of war. All too often, a local Nazi bigwig incited townsmen to fight to the death, then, just before the Americans attacked, hit the road.

Model at first wanted to fight on. From Berlin, the High Command demanded that he stay put and defend “Fortress Ruhr.” Hitler promised to send a newly formed army, the Twelfth, as relief, hinting that “wonder weapons” would turn the tide. Model soon realized that neither the Twelfth Army nor miracle weapons would be materializing.

During Easter Week, April 1 to 7, the Americans solidified the ring enclosing Army Group B, placing four corps around the perimeter. Those forces immediately launched converging drives, squeezing the outmanned and unsupplied Germans into an ever-smaller space. By April 11, the pocket was half the size it had been on Easter; by April 14, American attacks toward Hagen, a city in the center of the encirclement, had split the pocket. Here and there, often encouraged by residents of towns they were crowding, German troops started surrendering. On April 14, with the pocket torn in two and German units short on ammunition and rations—the 116th Panzer Division had not one serviceable tank nor an artillery round to its name—mass surrenders began. “What’s the point in this?” a Wehrmacht man asked. “I have a wife and children.” On loudspeakers, the Americans called for the Germans to call it quits, and thousands, then tens of thousands, did. The POW tally reached 317,000, twice what U.S. Army intelligence had estimated. The human herd milled in barely fenced fields—“Rhine meadow camps,” Germans called them—stretching as far as the eye could see.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne german did not surrender.

Walter Model, crushed by the totality of his defeat, as well as by the news that the Soviets wanted to try him for war crimes, grew despondent. The shadows were closing in. His wife and daughter, one of his three children, lived in Dresden, and while they had been lucky enough to survive the terrible Allied firebombing in February, an air raid on March 2 destroyed the family home. Late that month, grasping the situation, Model had his personal papers burned. On April 15, more bad news: without a word to Model, LIII Army Corps commander Lieutenant General Fritz Bayerlein had surrendered his entire force. On top of all that, the field marshal learned this while diving for cover during a heavy American air attack on his Wuppertal headquarters. The final twin blows—Bayerlein’s stab in the back and his own brush with death—seem to have induced an epiphany. Model now saw himself abandoned from below by subordinates and betrayed from above by Hitler, whose promised relief army was a chimera.

Nevertheless, Army Group B’s commander would not raise the white flag. As the Führer had, Model had often derided the “cowardice” he thought General Friedrich Paulus had shown in letting himself be taken prisoner at Stalingrad on January 31, 1943, one day after Hitler had elevated him to field marshal. “A field marshal does not become a prisoner,” Model had muttered. “It simply isn’t done.” The same day that Bayerlein gave up, Major General Matthew Ridgway, commander of the U.S. XVIII Airborne Corps on the southern face of the pocket, sent Model a letter demanding he surrender in language that blended conciliation and threat. In his communiqué Ridgway invoked “a soldier’s honor,” as well as the “German lives” and the “German cities” Model would save by surrendering immediately. The Prussian refused even to consider the American’s overture; he had other plans.

On April 17, Model decided to dissolve Army Group B; his men could find their way home. The order was ex post facto: Army Group B had already dissolved. “What is left for a defeated general?” the field marshal asked his chief of staff, General Carl Wagener, that day. Wagener said nothing. “In ancient times,” Model continued, “they took poison.”

On April 21, on the run and fresh from hearing Joseph Goebbels on the radio call on the German people to fight on without “weakness or wavering,” Model took leave of his aides outside Duisburg. He trudged into a beautiful copse of tall oaks and, with his Walther 6.35mm service pistol, shot himself.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]iming is everything, and the Battle of the Ruhr Pocket had the unfortunate timing to occur near enough to Germany’s surrender to be consigned to its shadow. (See “Countdown to Victory,” below.) To regard the confrontation in that way, however, is to read backward. The German surrender took place so quickly precisely as a result of the all-encompassing nature of the American achievement, which ripped the heart out of the German army in the West.

In the Ruhr, the Wehrmacht proved unable to match the Americans in a contest of maneuver, or successfully slug it out with them. Many of Model’s soldiers did present stiff resistance, and some 100,000 Germans died in the Ruhr fighting, but those sacrifices went for naught.

The Ruhr, font of German military hardware, was where Germany’s army died, where German dreams of world conquest dissipated, and where modern Germany began to become what that nation was destined to be all along: an important regional power, not a global juggernaut.

Rather than live with such a reality, the German commander in the Ruhr—Model— shot himself, as his Führer would nine days later. Their life’s work of bringing the planet under the Reich’s heel had come to nothing in the course of two world wars.

The U.S. Army, by contrast, came of age in the Ruhr. Like the Germans, the winning side could claim a dead general—not a suicide in a dark wood but a hero on the verge of triumph: Major General Maurice Rose of the 3rd Armored Division, who died boldly riding forward to be with his men in the thick of the fight. American troops fought a battle of maneuver to perfection, deftly synchronizing fire and movement and proving, once and for all, that when their nation is threatened, soldiers of a democracy will fight like lions. Moreover, they did these things at the end of a 4,000-mile logistical pipeline, and at a cost of only 10,000 casualties, remarkably light by late-war standards.

A year before the Ruhr, the U.S. Army had been mired in an attritive grind of a campaign in Italy; nine months before, its lead assault waves had barely gotten ashore at Omaha Beach. Since then, the forge of battle had tempered that force into a new superpower’s terrible swift sword. ✯

This excerpt was originally published in the May/June 2015 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.