Captured by photographer Herman Schnipper, the USS Astoria endured the three-hour frenzy during the bloody fight for Okinawa

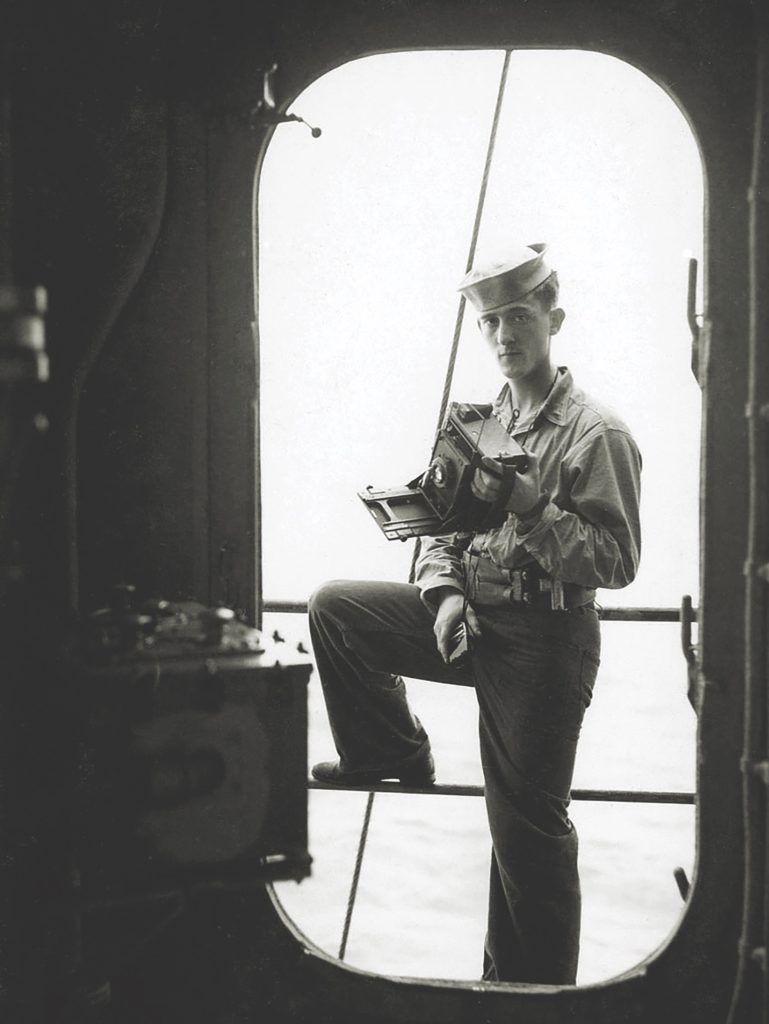

THE OVERCAST DAWN of April 11, 1945, brought no visible sunrise, just another order to general quarters. Across the light cruiser USS Astoria (CL-90)—“Mighty Ninety” to the crew—men raced to their battle stations. Such mornings had grown commonplace over the past four months. After protecting the flattops of the Fast Carrier Task Force during airstrikes in the Philippines, the South China Sea, Iwo Jima, the Japanese Home Islands, and now Okinawa, a once-neophyte crew had grown salty. Photographer’s Mate Third Class Herman Schnipper held his navy-issue Graflex Anniversary Speed Graphic medium-format camera at the ready with plenty of film handy.

Based on the past few days, action shots would come. When the U.S. Tenth Army had landed at Okinawa on April 1, Astoria and the fast carriers conducted offensive missions to suppress the Japanese response, as they had been doing for weeks prior. U.S. Navy and Marine aircraft bombed airfields, strafed enemy planes on the ground, and intercepted them in the air—everything to soften resistance the landing forces might face. The invasion codenamed Operation Iceberg had been inevitable—no secret to Japan—as Okinawa was the final steppingstone in an island-hopping campaign taking Allied forces to Japan’s doorstep. So from the first day, enemy planes targeted the Fast Carrier Task Force in return. Increasingly those attacks included the most desperate of all: suicidal kamikaze strikes aiming to sink or damage the aircraft carriers bringing so much floating airpower over a critical island stronghold. Across the 30-odd vessels surrounding Astoria in formation, men stood at their guns, lookouts scanning the skies. For Herman Schnipper, his assigned role would also be to pull the trigger and shoot—photographs.

Hailing from Bayonne, New Jersey, the wiry 21-year-old lucked into a photographer’s role upon induction into the navy. He did not attend the photography schools of the larger units stationed across the fleet; he simply owned a 35mm camera and knew how to use it. Before long he was issued his Speed Graphic and assigned routine work as needed. As Astoria trained and joined the fleet, Schnipper learned to love his work. Far from the mundanity of shooting portraits for sailor ID cards and personal photo requests for a wife or sweetheart, capturing operational images brought a thrill. The December 1944 typhoon, the bombardment of Iwo Jima, even refueling operations—Schnipper’s tiny darkroom below decks began to fill with enlargements of favorites he secured to the walls. He always sought to land another shot worthy of Our Navy magazine. Yet Okinawa was proving to be different—more taxing—given the daily onslaught of counterattacks.

Schnipper had grown accustomed to having full run of the ship during general quarters; he wasn’t tied to a gun mount or any other specific station. He learned during training exercises and then in combat that the fire control decks were far from ideal locations for photog work. While positions high up in the ship provided long views and unobstructed sightlines, the five-inch secondary mounts directly below them tended to shake a man to the core and toss him around. Even the fire controlmen and the ship’s captain, George C. Dyer, complained about that Cleveland-class battery configuration.

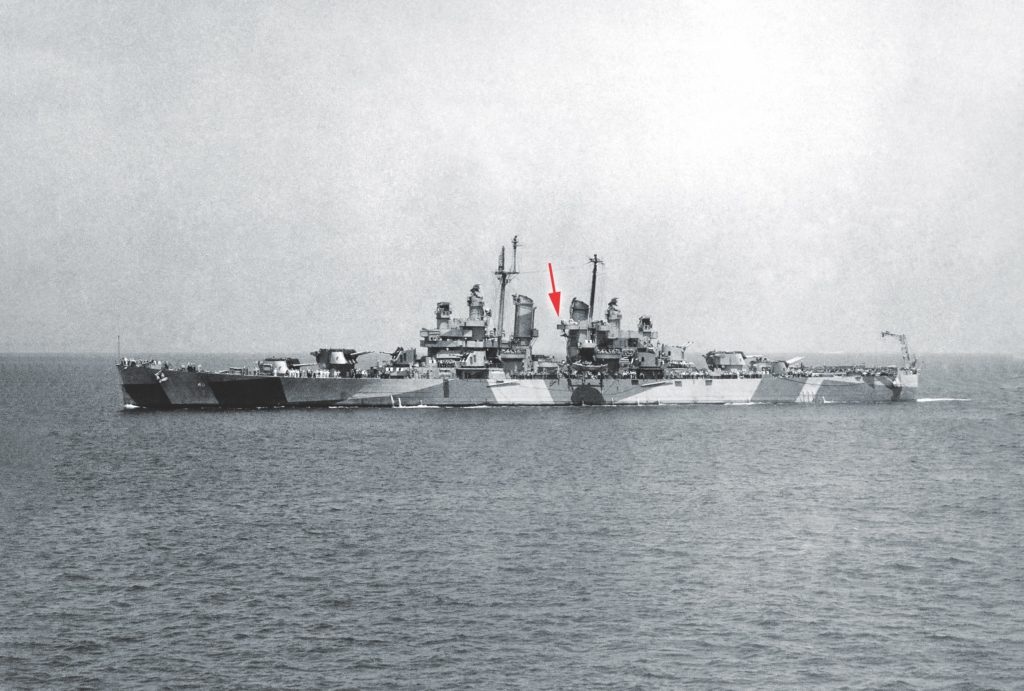

The photographer landed on a suitable alternative: he took position in the main searchlight platform protruding from Astoria’s aft funnel. High in the superstructure, with unobstructed access to vantage points port and starboard, the platform offered the additional benefit of distance from the guns. Plus he had it to himself; no one manned its 36-inch General Electric lamps in broad daylight. Exhaust fumes from the forward stack proved a small price to pay for not having to endure muzzle blasts when working on framing a shot.

He didn’t mind the solitude. His singular role on a ship of 1,300 men already rendered him an outsider. His Jewish faith amplified this isolation; men brought their prejudices aboard ship with their seabags, and some of the same sailors who hounded him for photographs used ethnic slurs behind his back. Just as his darkroom compartment became a place of refuge, so did the searchlight platform. Schnipper had grown accustomed to the bulk of the camera beyond his gray-painted M1 helmet and sweaty, full-body experimental flak suit, even when climbing ladders. After months in theater, the Speed Graphic felt like an extension of his arm. From his searchlight perch, Schnipper would be ready to capture whatever might ensue.

NOT THAT THE MORNING brought much. Heavy overcast, rain, and whipping winds brought terrible flying conditions for aircraft operating from the carriers. There were only so many photographs one could take of Corsairs, Hellcats, Avengers, and Helldivers launching for perimeter patrols and strikes over target areas. For Schnipper, that particular novelty had worn off long ago, and the day’s weather sealed the deal. Still, he waited as the steady drizzle soaked into his suit.

If the past three weeks served as any indication, photo opportunities would be plentiful. Beginning in mid-March, the first phase of pre-invasion fast carrier operations had focused on reducing Japanese air capability from Kyushu, the southernmost of the Japanese Home Islands. The carriers paid dearly for their efforts. USS Franklin, burned and gutted, now steamed stateside for massive repairs. USS Wasp followed suit, also heavily damaged from bombing during the strikes. USS Randolph had been struck by a kamikaze before even leaving the carriers’ anchorage at Ulithi Atoll, more than 1,500 miles south of Japan; after a month it was just joining the fray. A fourth fast carrier, the venerable USS Enterprise, had been hit on March 20 by friendly fire from another ship in Astoria’s task group, an event Schnipper had captured on film. As a result of these carrier losses, the Fast Carrier Task Force entered the April 1 Okinawa landings with fully one-quarter of their force projection capability off the line.

Even after six months in use, kamikaze attacks remained highly censored from the American public. While the Astoria crew had first learned of the Japanese suicide tactic back in December when they were en route to join the fleet, they had yet to see it successfully employed. Suicide planes had struck carriers during the Philippine and Iwo Jima operations early in the year, but never within Astoria’s immediate formation of ships.

At Kyushu, Herman Schnipper had captured images of kamikaze planes diving on the nearby USS Essex and other carriers, all brought down short of their targets by antiaircraft gunfire from surrounding ships of the screen. Some of those images now hung in his darkroom. For days at a time, men slept and took meals at their stations, successfully fighting off the enemy when raids appeared. While repelling such attacks, Schnipper and his shipmates learned a serious side effect of low-flying Japanese planes screaming by: they were causing American ships to fire into one another. On the same afternoon that friendly fire had damaged Enterprise, Astoria had been hit by a five-inch round from a neighboring ship. The shell pierced Astoria’s bridge armor, even peppering Captain Dyer’s flak suit with metal splinters. Yet the month ended without a single kamikaze hit on a ship in Astoria’s task group.

That changed five days earlier. On April 6, Schnipper witnessed a glancing kamikaze blow to the light carrier USS Cabot. The friendly fire effect persisted during the attack, as Astoria put a round into the aircraft crane of sister cruiser USS Pasadena, killing a Marine. Such incidents abounded even as ships worked to cut off their fire earlier.

The next day, an excruciating tradeoff ensued when a Japanese plane dove at the USS Hancock. When Astoria and other ships stopped shooting at the kamikaze, with no clear shot and their own ships in the line of fire, a suicide crash delivered a devastating blow to Hancock. As the crippled Essex-class carrier maneuvered, engulfed in flames and smoke, men across Astoria feared all would be lost. Their guns silent, helpless shipmates could only watch and hope that the men of Hancock who were blown into the water or forced overboard by flames could be fished out by destroyers. Sickened, Schnipper reluctantly took photographs for the ship’s action reports while lamenting his lack of zoom optics for the Speed Graphic.

Effective damage control by its crew extinguished Hancock’s fires, but the attack meant yet another carrier was out of action, forced to retire at the cost of 62 men killed and many more wounded. Hancock became the latest casualty in a war of attrition where one man could sacrifice his life to take an entire aircraft carrier off the line and reduce American striking capability by almost 100 planes.

Between almost daily attacks leading to attrition, numbing fatigue, mounting casualties, and friendly fire damage, by April 11 Operation Iceberg was proving to be a slog. One bright spot brought encouragement for the day: Schnipper noted that their old friend Enterprise, the “Big E,” had just returned to join their task group last night, back from repair. With five aircraft carriers surrounded by their protective screening ships, Astoria’s group made for a formidable force. It also offered a ripe target.

BY EARLY AFTERNOON the overcast had dispersed and visibility improved, making for better flight conditions. Men had learned that such improvement worked both ways and, sure enough, shortly after 1:30 p.m. reports came in of large numbers of likely enemy planes in the area. Carriers scrambled additional aircraft to intercept them beyond range of the two task groups on station.

Shortly before 2 p.m. a report came from USS Kidd, a destroyer on picket station outside the group and 28 miles northwest of Astoria’s position: the Kidd had been attacked, and “bandits” were inbound. Men readied at their guns. Within minutes, lookouts spotted a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighter making a run at Enterprise from astern. Schnipper rushed to the searchlight platform’s starboard railing. Astoria didn’t have the range to engage, but the battleship USS South Dakota did, joining Enterprise in blazing away at the diving plane. The fighter fell short, splashing off the starboard quarter of the carrier. Schnipper clicked the shutter at the exact moment a water plume shot higher than Enterprise’s masts under a sky peppered with antiaircraft flak bursts. He hoped he had the shot.

Less than five minutes later, a second plane dove on the “Big E,” identified as a Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” reconnaissance plane. Even as Enterprise executed an emergency turn, the Judy crashed just off the carrier’s port side, striking 40mm mount shields as it plunged. The plane’s unreleased bomb detonated under the ship, throwing one man overboard.

At the same moment, the carrier USS Bunker Hill and light cruiser USS Wilkes-Barre brought down another Judy to Astoria’s port side. The same pair of ships then downed a dive-bomber immediately on the Judy’s heels; both planes splashed off the bow of Bunker Hill. Schnipper missed the action; caught between port and starboard, a lone photographer couldn’t be both places at the same time. Nor had Astoria been in a position to fire from either side; it would have been shooting toward its own ships.

At 2:15 a fifth plane, a Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” army fighter, barreled in toward Essex, off Astoria’s starboard beam. With range and a clear target, this time the “Mighty Ninety” roared. Opening up along with Pasadena and Essex, the trio tore the tail off the plane. Spinning out of control, it hurtled to the water off Pasadena’s starboard beam. Another mountainous spray erupted under the blackened skies. Click went the shutter. Schnipper believed he had a good shot, but he couldn’t be sure until he developed his images. It occurred to him that combat photographers aboard surrounding ships surely captured many of the same events from differing vantage points.

A lull in the action brought a breather for the photographer, new strikes launching from the carriers—and an unexpected visitor to the searchlight platform. Much to Schnipper’s surprise, he looked and noticed Astoria’s chaplain, Al Lusk, standing behind him. Schnipper immediately recognized the tall, slender Baptist “jack of all faiths” from Friday night prayer services. He also knew the chaplain had no business being exposed high in the superstructure, and the lieutenant wasn’t wearing any protective gear to boot—neither a helmet nor a flak suit. The photographer’s instinct was to remind the chaplain of this, but the “padre” was an officer. He was also an avid shutterbug who wanted to see some action. The young enlisted man kept his mouth shut on the matter.

Schnipper instead showed Lusk around his camera, explaining its intricacies. Their photography lesson was interrupted at 3 p.m. by the jarring sound of surrounding gunfire as more inbounds approached. Astoria joined in, elevating the cacophony. Schnipper scanned the sky for flak bursts and spotted a diving Judy, again headed toward Enterprise. Chaplain Lusk positioned himself behind the photographer, like an umpire to a catcher. The Judy dove hard and crashed close aboard Enterprise, throwing debris into the air. A delayed thunderclap reached the two men, who observed fires breaking out on the carrier’s forward flight deck: a pair of F6F Hellcats on the catapults appeared to be burning. Schnipper snapped a quick photo, but Enterprise was steaming farther away and its emergency turns created a poor angle for an image. He knew from this distance he wouldn’t capture much.

Immediately after, the photographer and the chaplain watched as another plane approached the “Big E” from the same bearing, but antiaircraft fire and a pursuing Hellcat chased it off. As the plane sped away, gunfire from their ship again jolted the pair, this time back to port. They crossed the platform in time to see a Zero taking hits as it approached Bunker Hill. White flashes popped across the fuselage of the plane as rounds riddled the suicide attacker. Much to Schnipper’s horror, the crippled aircraft veered toward Astoria. Staring down a spinning propeller, Schnipper in that moment had the same thought as most sailors and Marines in such circumstances—he’s coming straight for me.

Bunker Hill continued to fire as the plane spiraled and fell. While Schnipper tracked its fall through the viewfinder, Lusk clearly saw a muzzle flash from Bunker Hill’s forward five-inch mounts. The plane isn’t the only thing coming straight for us.

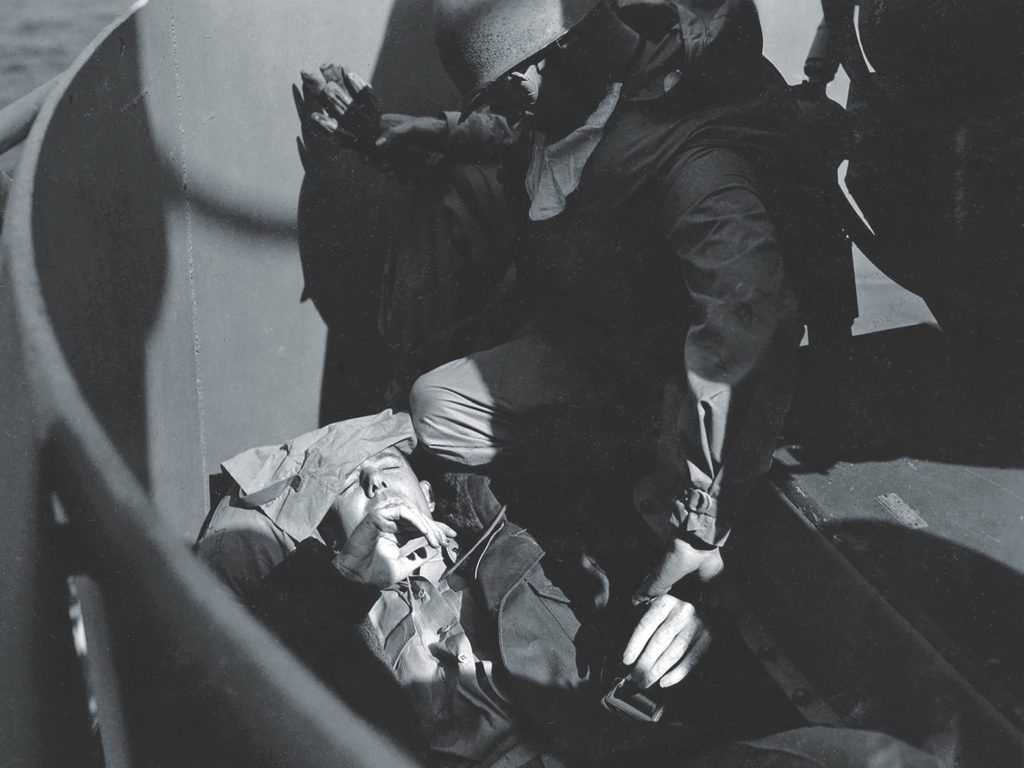

“Get down!” Lusk shouted just as Schnipper clicked the shutter. The chaplain dove on top of the photographer, driving him to the deck. The late round slammed into Astoria’s stack at high velocity and exploded, sending steel splinters flying. All fell momentarily silent as Lusk rolled off Schnipper. Composing himself, Schnipper realized Lusk was wounded, writhing and groaning. He leapt to the edge of the platform and shouted down for a corpsman. Looking back across the ship toward Enterprise, he saw that its fires had been extinguished. Its crew had come up with a novel solution for the burning Hellcats: they launched the planes down the catapults and into the sea.

Waiting for help, Schnipper set his camera aside to comfort Lusk. As he did so, two more Zeroes screamed past in succession with Astoria’s guns, among others, blasting away at them. The starboard 40mm gun crews found their mark and dropped the first plane, but there would be no photographs. Schnipper didn’t need one in this instance; he and others across the ship saw an image they would carry through life. The plane had been so close that even beneath a flight helmet and goggles, they could make out the Japanese pilot’s face looking back at them. Far from the cartoon caricatures drawn in the papers, they looked into the eyes of a terrified kid who died moments later.

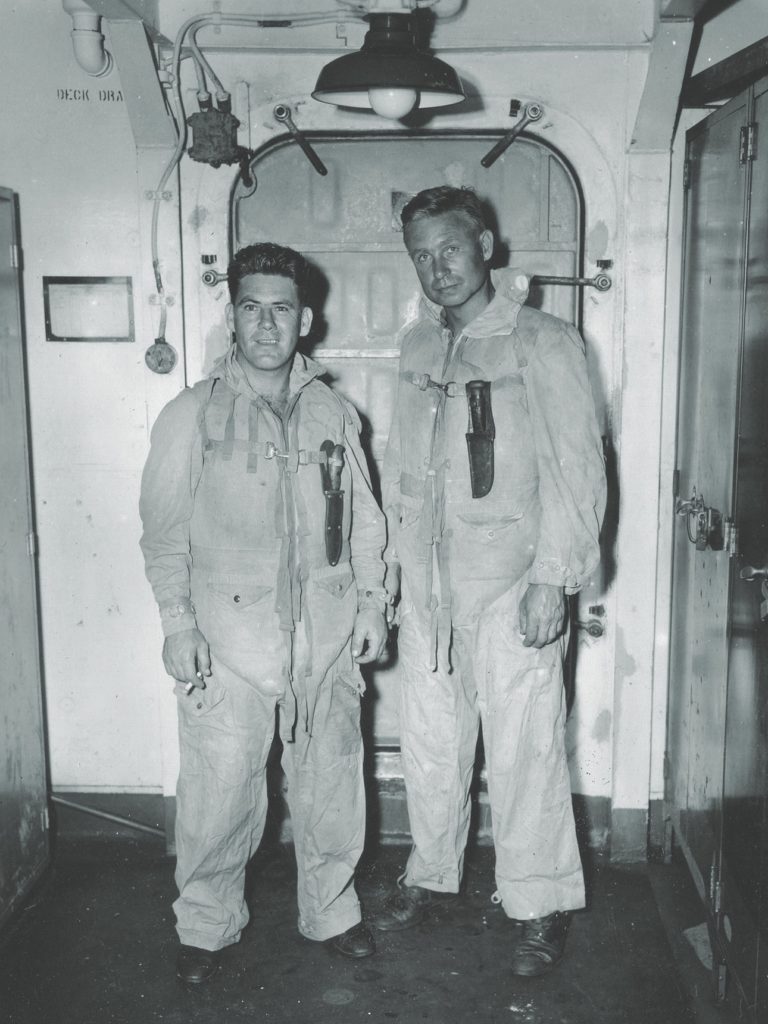

A corpsman in full flak gear clambered up the ladder with his medical kit. Removing his gloves, the corpsman checked Lusk’s pulse as Schnipper captured the scene—an action within the four walls of his duties. Only then did he realize he had also been hit—splinters of steel embedded in his face. He calmed himself and plucked the small shrapnel out.

Lusk wasn’t so lucky—he bore the brunt of the impact and had significant shrapnel embedded in his back. It missed the spine—he could move his hands and feet—but he was going to require emergency surgery. Another casualty of friendly fire. Getting him down from the platform would be the first challenge. The corpsman rigged a rope seat, and Schnipper helped him gingerly lower the wounded chaplain to waiting hands below.

More planes came in through the five o’clock hour. Astoria brought one down outside the formation at 16,000 yards, and another crashed into the water near Bunker Hill after taking hits from multiple ships. By 5:30, dusk rendered further photography impossible, even if attacks developed. Before descending the ladder, Schnipper took one last shot for the day: Supply Division sailors cracking open cases of K-rations. With the ship remaining at general quarters into the evening, there would be no action in the messing compartments. The crew would eat dinner again at their stations.

REPORTS CAME IN from other ships. While Schnipper had been tending to Lusk, one of the passing Zeros dropped a bomb that had narrowly missed Essex. Detonating below the waterline, it wounded 20 men. While Essex would remain on station, picket destroyer Kidd would not. It had been struck low to starboard by a suicide plane, then successfully fended off a follow-up. Kidd would have to retire for anchorage to be patched up and sent stateside for extensive repair. In Astoria’s neighboring task group, the battleship USS Missouri had received a glancing yet harrowing blow: shattering on impact, the Zero hurled parts of the Japanese pilot onto the deck. As Enterprise prepared to retire once again for repairs, its men posed with a trophy: the wing of the third attacking Judy had been thrown onto the flight deck when the plane exploded against the side of the ship. One of Schnipper’s fellow combat photographers took a picture of a shipmate standing next to the propped-up wing which had been marked, “Hands off.” Enterprise had been back in the group for exactly one day.

On this April 11, USS Astoria’s task group endured attacks from no fewer than 13 consecutive Japanese kamikazes over a three-hour period—the heaviest concentrated effort they had yet experienced. Despite well-coordinated antiaircraft fire across the group, the day once again knocked vital ships out of action and pulled others away to escort the “cripples” back to Ulithi.

Chaplain Lusk was going to make it. Astoria’s doctor determined that he could perform the surgery aboard ship. Nevertheless, Captain Dyer fumed at his padre for venturing where he had no business during general quarters, let alone active combat. Much to his ire, the captain also knew he would have to put Lusk in for a Purple Heart, a rare medal for a ship’s chaplain.

In the late evening, after chow and headed to his darkroom sanctuary, Herman Schnipper looked up to watch flares dropping from enemy planes all around the task force, tracking their movement. Astoria’s five-inch guns occasionally fired via radar-guided direction—brilliant flashes of light, but little opportunity for still photography. He set out to get some rest; morning would again come soon.

Three days later, on April 14, Astoria retired to meet its replenishment group some 250 miles southeast of the strike area. Fueling and resupply brought no rest for the weary—just a different form of strenuous activity after five days on station. The light cruiser would steam back to the operational area overnight for the next stint. As nets of supply crates and boxes came across from the oiler alongside, Schnipper hoped for film and developing supplies.

Chaplain Al Lusk remained in sickbay while recovering from surgery. He also survived his tongue-lashing from the captain. Nevertheless, after the crew learned that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died on April 12, Lusk insisted upon leading the men in prayer from his bed.

Once he could, Herman Schnipper developed his film. Several shots turned out well, but one in particular made him smile to himself: the image would win no accolades, but he had indeed captured the muzzle flash from the round that struck the stack just as the padre pounced.

In the evening at least the men got a hot meal in the messing compartments. They would be back at quarters before dawn, still no end in sight. ✯

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.