This onetime sandbar in the Mississippi River off St. Lous was the scene of duels between “gentlemen.”

IT EMERGED INNOCENTLY enough around 1798, quietly and ever so slowly surfacing above the muddy Mississippi River. At first, it was just one among the thousands of sandbars that are born and die each year as the mighty river ebbs and flows. But this particular patch of ground had a more enduring destiny in the affairs of honor among 19th-century gentlemen.

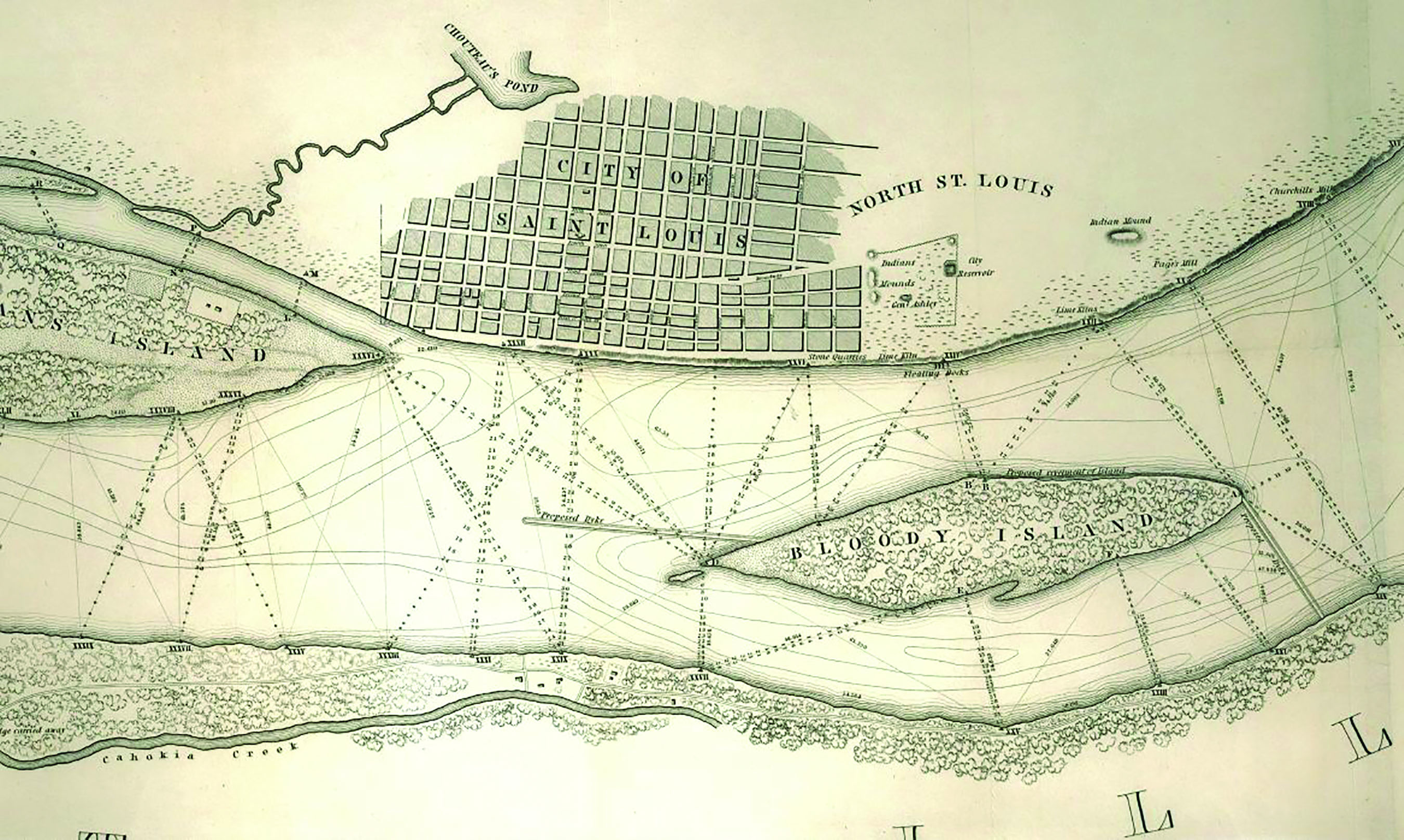

Known as a towhead, the alluvial island lay smack between Missouri and Illinois and directly across from St. Louis. But as it was so insignificant, neither state moved to claim ownership. It surfaced in an era when a dwindling number of upper-classmen, particularly in Missouri, every so often waged duels with pearl-handled revolvers, adhering to a gentleman’s code of honor that had originated in Europe in the Middle Ages.

By 1877 the practice had become so well established in Ireland that adherents saw fit to pen a formal “code duello.” It enumerated more than two dozen rules of conduct governing a challenge to regain honor in the event a gentleman dared defame another in public. Were an apology not forthcoming, the rules permitted the challenged party to choose the weapons, the ground and the distance. How many volleys the duelists fired depended on the gravity of the offense. Societal pressure demanded a gentleman defend his honor. Refusal might jeopardize one’s career, particularly in the legal, publishing or political professions.

By the early 1800s, however, both Missouri and Illinois had moved to outlaw the barbarous custom. So, where to duel? Thus the seemingly inconsequential towhead in the midst of the Mississippi—without name, owner or laws—became the perfect place for gentlemen to settle disputes, a no-man’s-land where men could rendezvous to defend their reputations and spill blood without fear of penalty.

In the first recorded duel there, in late December 1810, attorney James Graham shot it out with Dr. Bernard G. Farrar, the first American physician to practice west of the Mississippi. The good doctor was defending the honor of a friend whom Graham had accused of cheating at cards. His “second” in the duel was none other than famed explorer William Clark. Over the course of three volleys, Farrar was grazed in the buttocks by a slug, while Graham was hit in the legs, right hand and side, the latter ball lodging in his spine. Dr. Farrar felt compelled by oath to tend to his opponent, but Graham later died of his wounds.

Another notable duel on the island touched off at 6 a.m. on Aug. 12, 1817, between prominent St. Louis attorneys Thomas Hart Benton and Charles Lucas. In the wake of a rancorous court case, the men had exchanged harsh accusations and insults, prompting Lucas to challenge Benton. In the initial volley, Lucas took a slug to the throat, while Benton was grazed in the right knee. When Lucas proved unable to rise for a second shot, the duel was suspended. Both men ignored appeals from friends to make amends, and weeks later Lucas had recovered sufficiently to arrange a rematch. In the second duel, on the morning of September 27, Benton shot his rival through the heart, and Lucas died within minutes. Emerging unscathed with his reputation unblemished, Benton was later elected to the U.S. Senate and represented Missouri for 30 years.

A duel with a more unusual outcome occurred at 5 p.m. on Aug. 26, 1831, when Major Thomas Biddle, a distinguished War of 1812 veteran, and U.S. Representative Spencer Pettis of Missouri faced off. Historians believe it was their meeting that led to the towhead’s designation as Bloody Island.

In an exchange of fiery political speeches Pettis had publicly railed against Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States, and Biddle’s brother Thomas took offense to the remarks. Amid the ensuing war of words in the St. Louis press, Biddle called Pettis “a dish of skimmed milk,” while Pettis questioned Biddle’s manhood. When the debate flared into physical violence, the congressman challenged the major to a duel. As the challenged party, Biddle was allowed to choose the weapons and the distance. Being nearsighted, he chose pistols at just 5 feet. Given the range, when the duelists triggered their weapons, both suffered mortal wounds that ended their lives within days. However, each remained conscious long enough to forgive the other.

Over the next two decades, Bloody Island grew, reaching 1 mile in length and some 500 yards in width. By 1837 it was diverting sediment largely to its Missouri side, threatening to choke off the channel to the St. Louis waterfront. If left unchecked, the once insignificant sandbar would have had a pronounced impact, landlocking one of the busiest commercial ports on the Mississippi.

First Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, then a member of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, devised a system of dikes that directed the current toward the channel off St. Louis, deepening it for navigation. The diversionary tactic by the future Confederate general also eliminated the channel on the opposite side of the island, and by the mid-1850s it was fused to the Illinois shore. Still, duels between men of note persisted on the infamous tract of land.

No less a gentleman than future President Abraham Lincoln traveled to the dueling ground on Sept. 22, 1842, to settle a dispute with one James Shields. Missouri State Auditor Shields issued the challenge after Illinois State Representative Lincoln published a letter ridiculing Shields in the Springfield, Ill., Sangamo Journal. As the challenged party, Lincoln chose the cavalry broadsword, which would give him the advantage due to his height. On the appointed day Lincoln reportedly lopped off the branch of a tree with his sword, to demonstrate both his advantage as well as the damage that potentially awaited his opponent. Whether true or not, friends of both men convinced them to call a truce, and the confrontation was over before it commenced.

What is thought to have been the final duel on the “island” occurred on Aug. 26, 1856, after years of bitter political sparring between Thomas Caute Reynolds and Benjamin Gratz Brown. Reynolds, a U.S. attorney in St. Louis who opposed emancipation, challenged Brown, editor of The Daily Missouri Democrat, who favored emancipation. Reynolds emerged from the duel without a scratch, while Brown was wounded in the leg and limped for the rest of his life. The match came to be known as the “Duel of the Governors,” as in 1862 Reynolds became Confederate governor of Missouri, and Brown was elected governor of Missouri in 1870.

By the late 1850s dueling had fallen out of favor in most places. Libel law became the weapon of choice, and the courtroom the new “field of honor” on which men defended their reputations. Out West, of course, gunfights persisted, but rarely in face-to-face encounters as depicted on TV and film.

Today the blood-soaked ground that emerged so long ago from the Mississippi and attached itself to the Illinois shore is hemmed in by highway overpasses and crossed by railroad tracks.

This story was originally published in the April 2020 issue of Wild West Magazine. To subscribe, click here.