Railroad detective William D. “Bill” Fossett and U.S. Express Company guard Jake Harmon began walking forward from the rear of the train once the shooting stopped and the smoke cleared on the night of April 9, 1894. The Rock Island Railway’s southbound train from Wichita, Kansas, to Fort Worth, Texas, had been attacked by bandits on the wide-open stretches of prairie just south of Round Pond (also known as Pond Creek), Oklahoma Territory.

Sprawled along the tracks near the express car lay the lifeless body of an outlaw, felled by buckshot from Harmon’s shotgun and a bullet from Fossett’s rifle. The Pond Creek Tribune reported he “was lying on his back with his elbow resting on the ground and a revolver clutched in his right hand pointing straight up in the air.”

The revolver was a nickel-plated Colt Model 1878 Frontier double-action with a 7-inch barrel. The man holding it in a death grip was initially identified as either “Bill Rhoades” or “J.W. Pitts,” aliases, it turned out, used by Bob Hughes, a once-indicted whiskey peddler and would-be bandit. The next day, a Caldwell, Kansas, newspaper described the dead train robber in detail:

He had two purses, one with $2.10 in it, the other was empty. On the inside pocket of his coat was an unsigned letter containing threats against certain persons whose names are withheld for obvious reasons. The dead man stood in life about five feet five inches and weighed about 120 pounds….He wore a cheap coat of brown material and his checked pants were stuffed into a pair of boots that encased his legs almost to his knees. He wore a soft hat. There was nothing about his appearance to indicate that he had been a “bad” man; certain it is he was not a “terror.”

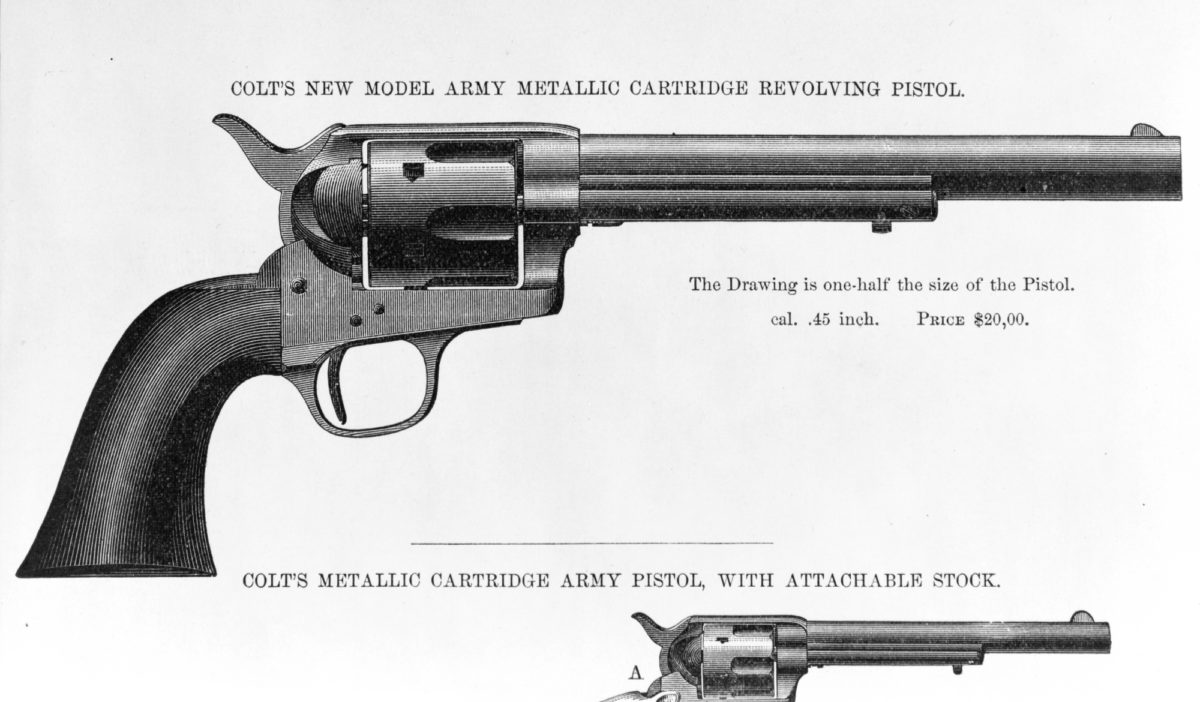

A “terror” or not, Hughes was no slouch when it came to weaponry. The Model 1878 was the double-action version of Colt’s famed Single Action Army revolver. It saw service in the West and over most of the world until production ended in 1905. This six-shot revolver had bird’s-head grips made of either walnut or checkered hard rubber. It came in three standard barrel lengths with an ejector assembly, and three shorter barrels without the ejector. Cartridges were loaded through a thin, right-side loading gate in cylinders that held .32-20, .38-40, .41 Colt, .44-40, .45 Colt, and .450, .455, or .476 Eley calibers.

Bob Hughes’ Model 1878 was Serial No. 29674, chambered in .45 Colt. The manufacturer’s records show shipment from Hartford, Conn., to the Chicago distribution firm of Hibbard, Spencer, Bartlett & Company on January 18, 1892. Its history between then and the time it was found on Hughes’ body is unknown, but within a few days of the attempted train hold-up, the revolver, holster and gun belt were given to a Rock Island Railway manager named Harry Fox, who worked in the company’s Kansas division, then covering parts of Oklahoma Territory. Fox, from Reading, Pa., had spent most of his railroad career working in Des Moines, Iowa, but was transferred westward to Herington, Kan., in 1892.

According to the railroad man’s late son, Harry Jr., a deputy U.S. marshal presented the gun to his father in gratitude for the railroad’s help in pursuing outlaws. Indeed, there are several recorded instances of posses using “special” Rock Island trains to pursue bandits. It is likely that Deputy Marshal Chris Madsen, (who, along with Heck Thomas and Bill Tilghman, became known as the the “Three Guardsmen of Oklahoma”) investigating the attempted train robbery for the U.S. marshal’s office, was the man who gave the gun to Fox. But no official record or newspaper account of the “gift” has been found, to date.

It is notable that beneath one of the cartridge loops on the gun belt there appears to be a bullet hole with traces of bloodstain around it, possibly marking the fatal wound caused by buckshot or a bullet. In 1937 the strapping 6- foot-4 Bill Fossett (1851-1940) recalled his part in the gunplay that night as one outlaw began shooting toward the passenger coaches: “I knew the fellow who was shooting back through the train…was none of the train crew. So I took a shot at him and he fell and the other robbers piled out of the express car and ran for their horses….”

Although the taciturn Fossett had once claimed he didn’t even carry a gun that night, Deputy Marshal Madsen, in his 1936 memoirs, explained: “Fossett does not tell you that he killed Hughes [a k a Rhodes and Pitts], but others who were there at the time say he was the only one with a gun and the grit to use it.” Unfortunately, Madsen entirely overlooked Jake Harmon’s role as, undoubtedly, shots from both men took a fatal toll. At the coroner’s inquest, Harmon testified: “There were three men standing east of the door of the express car. One of them held a revolver in his hand pointed into the car. I took aim and fired. The smoke was so dense I could not see the men after the first shot.”

Harmon, a former Wichita police officer before joining the U.S. Express Company, later commented that he would have “got more than one [robber],” but his shotgun “would not work right.” Although the rest of the gang besides Hughes escaped into the night, they did not remain free for long. Two of the bandits were arrested in another town the next day when they tried to trade their jaded horses. Fossett, meanwhile, developed leads on the remaining outlaws, and within days he and a deputy cornered suspects Nate Sylvia and Felix Young in El Reno. Sylvia surrendered, but Young tried to run away. When Fossett shot his horse from under him, the game outlaw took off on foot. After a running gunfight through the streets of El Reno, a shot from Fossett struck Young in the leg and he, too, surrendered.

Rock Island’s Harry Fox carried the outlaw’s revolver with him for the remainder of his career, especially when railroad business took him into Oklahoma Territory. In 2000 Tennessee gun collector Thurel Emerton purchased this storied Model 1878 Colt, later donating it to the Chisholm Trail Museum in Kingfisher, Okla., where it is now displayed with information on detective Bill Fossett.

Originally published in the December 2007 issue of Wild West.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.