In the predawn hours of Christmas Eve 1941, four warships closed in on their target: a small archipelago of eight rocky islands off the southern coast of Newfoundland. While the United States and Great Britain at that moment were organizing a multinational alliance against Nazi Germany and the empire of Japan, this was a different operation altogether. The target was French, the invaders were French, the enemy was French, and the isolated residents designated for liberation were French.

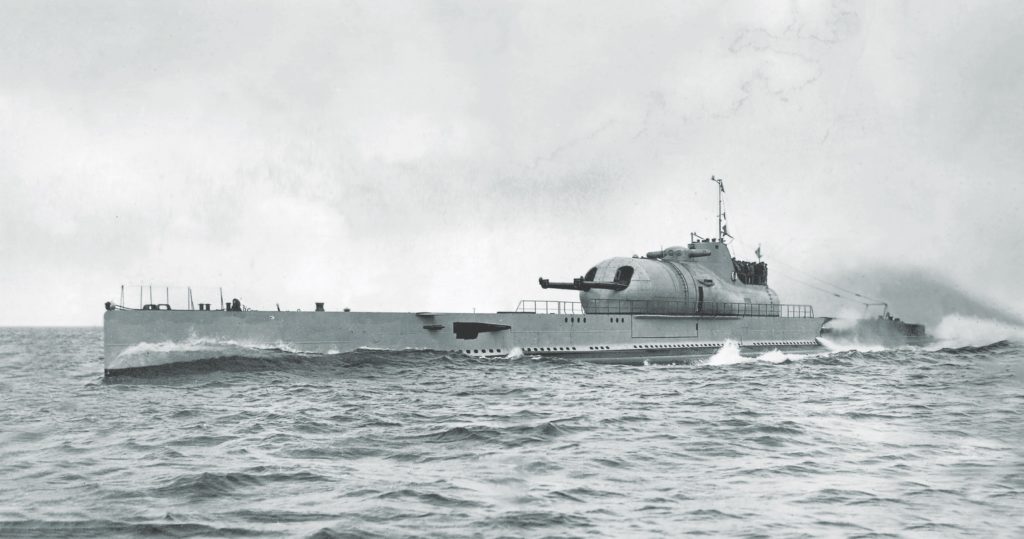

The ships—four Flower-class corvettes and a giant, one-of-a-kind cruiser submarine armed with twin 8-inch naval guns—were manned by 330 French sailors who had eagerly volunteered for the secret mission. Officially, they were a French component of the Royal Navy’s Western Approaches Command in Liverpool, a fleet of more than 300 escort ships responsible for protecting merchant convoys traveling between North America and the British Isles.

On this day, however, the warships were following orders from someone else: an exiled French army officer who had renounced his country following its surrender to Nazi Germany. Eighteen months after he announced the creation of les Forces françaises libres—the Free French—in a broadcast from London on June 18, 1940, Brigadier General Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle had just launched his own war against the collaborationist government of Vichy France.

The news that French sailors were landing on the two islands exploded like a bomb.

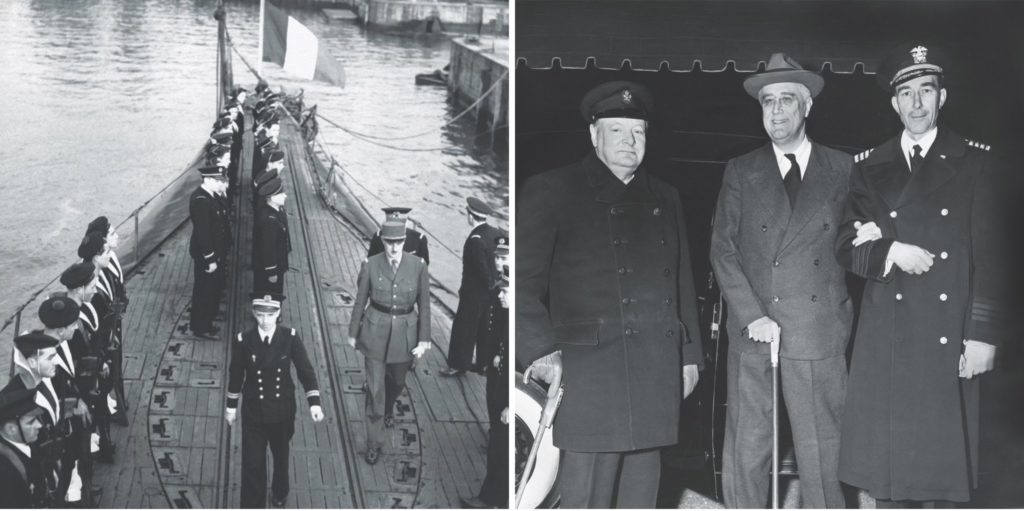

Under the ruse of a routine training mission, Vice Admiral Émile Muselier, de Gaulle’s naval commander in chief, had traveled from London to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he had ordered the warships to sea. Rather than carrying out routine U-boat tracking exercises, the force steamed steadily east-northeast on the 330-mile voyage into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and toward the French territory they intended to liberate.

In the end, the mission to the archipelago islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon—the oldest French possession in the Western Hemisphere—would have scant military impact on the wider global war. But the political consequences for the Western Alliance would be profound. The incident occurred as the critical Arcadia Conference between U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston S. Churchill was entering its third day in Washington, D.C.

Less than three weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor propelled the United States into World War II, Churchill had braved the German U-boats to cross the North Atlantic for a summit with Roosevelt. Arriving in Hampton Roads, Virginia, aboard the newly commissioned battleship Duke of York, Churchill and his staff had arrived in Washington on December 22, where they immediately met with Roosevelt and his commanders to wrestle with a host of difficult issues confronting the new wartime alliance.

The mood in Washington was dire. In the Pacific, Japanese troops had invaded the Philippines, Borneo, Thailand, Burma, Malaya, and the Chinese cities of Hong Kong and Shanghai and had taken U.S.-held Guam and Wake Island—all in less than three weeks. In western Europe, the swastika flew over the capitals of five conquered nations, and the German army at the six-month milestone of Operation Barbarossa had overrun most of eastern Europe and was entrenched at the outskirts of Moscow. At sea, German U-boats were hunting allied merchant ships from South Africa to the coast of Labrador.

The Arcadia Conference participants were confronting issues as profound as agreeing on a “Germany first” policy for the conduct of the war, combining the chiefs of staff of the two militaries, coordinating wartime operations, and setting a timeline for the liberation of North Africa and western Europe.

The sudden news that French sailors were landing at Saint Pierre and Miquelon—without so much as a by-your-leave from de Gaulle to Washington, Ottawa, or London—exploded like a bomb at the Arcadia Conference. But it was much more than an unwanted surprise: The independent military action illuminated a serious fault line in the Anglo-American partnership, landing Roosevelt and Churchill on opposite sides of the thorny issue of how to deal with occupied France. It was also a warning from de Gaulle that he would not allow the leaders of the alliance to interfere with his plans to become his country’s liberator.

Even though it shocked the Arcadia conferees, de Gaulle’s invasion of the French archipelago shouldn’t have been a complete surprise. Even before France fell to the invading German army in June 1940, the fate of Saint Pierre and Miquelon was under intense scrutiny in Ottawa and Washington. On June 5, two weeks before France surrendered to Germany on June 22, Jay Moffat, the U.S. ambassador to Canada, had approached the government of Canadian prime minister MacKenzie King with the possibility of American or Canadian occupation of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. But Moffat soon reversed course and urged Ottawa to take no action while Washington and the newly formed Vichy government negotiated diplomatic relations. The issue of the French islands south of Newfoundland briefly receded.

Coming to power after the fall of the French Third Republic, World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain had acceded to the brutal terms of the armistice with Germany. The Nazi regime annexed the Alsace-Lorraine region. The German army occupied France’s northern and Atlantic coast provinces, among them Île-de-France, which included Paris. German engineers began building five massive bases along the Brittany coast to give the U-boat force direct access to North Atlantic shipping lanes. Pétain was left with nominal power to administer the rest of mainland France from the small city of Vichy.

Vichy, however, still officially controlled vast French colonial holdings in Africa, Southeast Asia, the Levant, and French Polynesia. In North America, the French Empire had all but disappeared by the beginning of the 20th century. Where once France had controlled the interior of North America from Quebec to New Orleans, by 1941 it controlled only a handful of Caribbean islands as well as the tiny archipelago of Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

Pétain also remained commander in chief of the second largest navy in Europe. In June 1940, the French fleet included 1 aircraft carrier, 5 battleships, 19 cruisers, 71 destroyers, and 76 submarines. They were dispersed in ports as far afield as Toulon, France; Plymouth and Portsmouth, England; Dakar, Senegal; Mers-el-Kébir near Oran, Algeria; and Alexandria, Egypt.

From the moment of France’s surrender to Germany, the United States and Britain chose starkly different strategies to deal with the Vichy regime. With the United States still neutral, Roosevelt quickly established diplomatic relations with Vichy and sent Admiral William D. Leahy, the retired chief of naval operations, to France as ambassador.

Churchill and his cabinet took a much harsher stance. On July 3, 1940, just 11 days after the surrender, Churchill, fearful that the French fleet might fall into the hands of the Nazis despite the formalities of its neutral status, ordered Operation Catapult, dispatching a Royal Navy task force in the Mediterranean to neutralize or destroy the French warships at Oran and Alexandria. Britain also commandeered a half dozen French warships and submarines that had sought sanctuary in English ports. While the French naval commander at Alexandria agreed to neutralize his ships, the situation in Oran turned bloody. Approaching the anchorage at Mers-el-Kébir on July 3, British warships opened fire on the French, sinking one battleship and damaging two more and a pair of destroyers. The raid resulted in the deaths of nearly 1,300 French sailors. In retaliation, the Vichy government broke off relations with Great Britain and launched several air raids against the British colony of Gibraltar.

Having abandoned all ties with the Pétain regime, Churchill turned to the only alternative: Charles de Gaulle.

A combat veteran of World War I who was wounded three times and taken prisoner by the Germans, de Gaulle had risen steadily through the ranks of the French army during the interwar years. An expert in armored warfare, the 50-year-old colonel had been preparing to take command of the newly formed 4th Armored Division when Germany struck through the Ardennes in May 1940. Within a week, de Gaulle and his understrength division were in action in northern France. In two separate battles, de Gaulle managed to slow the German advance, dealing huge losses to its artillery and aircraft. Then-French president Paul Reynaud, recognizing de Gaulle’s bravery, promoted him to brigadier general and shortly afterward appointed him undersecretary of state for national defense and war with a prime responsibility for coordinating efforts with the British government.

It was while serving in this ill-fated role in the French government just as his country was at the verge of collapse that de Gaulle met Winston Churchill.

On June 9, 1940, de Gaulle flew to London for the first of several meetings with Churchill. The gaunt, 6-foot-5 Frenchman deeply impressed Churchill, who described his visitor as “a young and energetic general [who had given] a more favorable impression of French morale and determination” than his morose colleagues and superiors. The two men would meet several times over the following weeks, quickly forming a personal relationship that would survive numerous personal clashes over wartime decisions affecting the fate of France. This friendship would have deep consequences for Western Europe long after the war.

In the last week of the existence of the French Third Republic, de Gaulle was primarily an observer of the defeat of his army and, shortly thereafter, the collapse of the Reynaud government. In the escalating chaos, de Gaulle witnessed or worked on a series of desperate and stillborn plans to enable France to continue the fight: organizing a guerrilla war against the invaders inside metropolitan France; evacuating the government, first to a redoubt in Brittany, then to the Atlantic port city of Bordeaux, and finally to a safe location in French North Africa; even joining with Great Britain in a formal union to continue the struggle. But other French leaders by now were counseling armistice. Returning from a second trip to London on June 16, de Gaulle learned that Reynaud had resigned, Pétain was now president, and a formal surrender to Germany was imminent. De Gaulle would have none of it.

The following morning, de Gaulle flew to London on the British plane that had brought him to Bordeaux just the day before. Carrying only a pair of suitcases with his personal possessions, de Gaulle, once in London, immediately began his dogged effort to create the Free French. On June 18, the exiled general broadcast via the BBC a historic entreaty to his fellow countrymen:

I speak to you with full knowledge of the facts and tell you that nothing is lost for France. The same means that overcame us can bring us to a day of victory. For France is not alone! She is not alone! She is not alone! She has a vast Empire behind her. She can align with the British Empire that holds the sea and continues the fight. She can, like England, use without limit the immense industry of [the] United States.…I, General de Gaulle, currently in London, invite the officers and the French soldiers who are located in British territory or who would come there…to put themselves in contact with me. Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished.

Over the next five months, as he recruited staff and volunteer soldiers from the French émigré community and struggled with multiple internal struggles that at times threatened to paralyze the movement, de Gaulle launched a two-pronged campaign to create the Free French military. While shaken by the failure of a British naval task force to seize Dakar from Vichy in September 1940, de Gaulle’s allies in French Equatorial Africa soon scored a series of victories, persuading the colonial governments of Chad, Cameroon, and French Congo to switch allegiance from Vichy to the Free French.

In England, de Gaulle and Muselier toiled to assemble a small naval force from the vessels seized in Operation Catapult, as well as newer warships provided by the Royal Navy. The setback at Dakar and lingering resentment among many French émigrés in England over Operation Catapult slowed—but did not thwart—the emergence of the Free French navy.

From the very outset of this seemingly impossible quest, de Gaulle had his eye on Saint Pierre and Miquelon. But he would have to wait until he had a military force to do something about the islands.

By mid-1941, sailors flying the Free French flag with the Cross of Lorraine were commissioning corvettes and destroyers that became an integral part of the allied North Atlantic convoy escort program.

After the seizure of the French ships in British ports, the Free French navy had taken possession of several warships, including two World War I–era battleships, and the one-of-a-kind cruiser submarine Surcouf. While the two battleships never saw action at sea—serving instead as stationary depots or storeships—the Surcouf, under the command of Georges Louis Blaison, traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in early 1941, where it occasionally sailed was an escort for allied convoys. But the massive 3,300-ton submarine, which carried an observation floatplane in a closed hangar and sported a sealed turret with two 8-inch naval guns, proved to be an ungainly escort ship. Other seized French warships, including the destroyers Le Triomphant and Léopard, later joined the escort force with Free French crews. The Royal Navy also came to the aid of its Free French counterparts, providing nine Flower-class corvettes that would be flagged under the Cross of Lorraine.

Between the first week of July and Christmas Eve 1941, seven of the corvettes joined the Mid-Ocean Escort Force, a naval command of several hundred Allied warships that bore vital supplies to the British Isles. After a period of intense antisubmarine warfare training at Tobermory Bay on Scotland’s Isle of Mull, each ship was then assigned to a convoy escort group.

Like their British, Canadian, and Norwegian comrades who also served in the Flower-class corvette, de Gaulle’s sailors soon came to appreciate the small warship’s ability to operate in the storm-tossed North Atlantic. Each of the 925-ton vessels, just 205 feet long with a beam of 33 feet, carried a solitary 4-inch deck gun, two 20-millimeter Oerlikon cannons, and as many as 70 depth charges. Later, the corvettes would receive the forward-throwing Hedgehog antisubmarine mortar.

The corvette’s biggest limitation was its relatively slow speed. The Royal Navy by necessity had thrust the corvettes, essentially modified whaling vessels intended for service in coastal waters, into the midocean escort role. The corvette had only a single propeller shaft, and its maximum speed of 16 knots was slower than that of a Type VIIC U-boat on the surface. Nevertheless, the small warships became effective convoy escorts when teamed with the larger frigates and destroyers. But their crews paid a price.

One British corvette commander later spoke of his vessel’s tendency to “corkscrew” in heavy seas. “About the third dip [of the hull] and you get tons and tons of water come over the fo’c’s’le [forecastle], and if you happened to be in the waist [of the ship]…you probably get washed astern,” former Lieutenant Harold G. Chesterman recalled telling one of the corvette design engineers. “He looked quite surprised when we told him how good they were. Uncomfortable and lively and wet, but safe. And it didn’t matter what the weather was, we could go into the gale, down the seas, and when merchant ships were heaved to with the wind on the port bow…we could go anywhere.”

The first of the corvettes to take to sea was the Alysse, commanded by Lieutenant Jacques Marie Lehalleur with a crew of 70 Free French sailors. Commissioned at the George Brown & Company dockyard in Greenock, Scotland, on June 17, 1941, the corvette’s first deployment came four weeks later when it joined westbound Convoy OB349 for an Atlantic crossing. After 11 days at sea without a combat incident, the 59 merchant ships dispersed at a point in the western Atlantic 237 nautical miles northeast of St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Having gathered enough escorts by midsummer 1941, the Western Approaches Command reorganized the escort fleet into four groups: western and eastern local forces for protection at either end of the crossing, and a pair of midocean escort formations that would operate between North America and Iceland, and Iceland and the British Isles.

Between July 22 and November 3, 1941, six more Free French–manned corvettes followed Alysse into the convoy escort force. Four of them—Lobelia, Renoncule, Roselys, and Commandant Détroyat—served on the eastern leg of the midocean convoy routes. Two others—Aconit and Mimosa—joined Alysse operating out of Halifax with the western midocean convoy force.

Compared to 1942 and 1943, which saw horrific convoy battles, the second half of 1941 was relatively quiet on the North Atlantic. Several factors contributed to the respite. First, the success of British code breakers in identifying U-boat movements and ordering timely route changes for the convoys helped most of them avoid detection. A second factor was the quiet entry of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet’s destroyer force into convoy escort duties. Following the secret meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt at Argentia, Newfoundland, in early August 1941, American destroyers began shepherding convoys as they traveled from North America toward Iceland and back; in addition, the United States mounted a massive buildup of patrol aircraft in Iceland. During the next four months, U.S. warships would escort 17 convoys along the Grand Banks–Iceland leg of the Atlantic crossing. The third and most significant factor was an accidental gift from Adolf Hitler. Shortly before launching the invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Hitler ordered his U-boat force to avoid any confrontation with the U.S. Navy in the North Atlantic while the massive land operation was underway.

Despite those conditions, the Battle of the Atlantic threatened to erupt in savage violence at any moment. Three combat incidents—the encounter between the destroyer USS Greer and U-652 on September 4 with no casualties; the attack on destroyer USS Kearny by U-568 on October 17 that damaged the ship and killed 11 crewmen; and the sinking of USS Reuben James with the deaths of 100 of its 144-man crew on October 31—hardened the posture of the U.S. government toward Germany and quickly shifted the Atlantic Fleet from neutral patrols into an undeclared war against the U-boats.

During those five months, the Free French warships served in escort groups that ferried 37 convoys safely to and from the British Isles, protecting 1,665 merchant ships. All but 10 of the formations got through without a single combat loss. The escorts, including the Free French corvettes, were becoming a well-trained naval force.

So when de Gaulle and his naval commander, Vice Admiral Muselier, decided in early December to prepare a unilateral takeover of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, the Free French–manned Surcouf and three corvettes were at the ready.

By mid-December 1941, the 6,500 residents of Saint Pierre and Miquelon were in dire need of help—and the Vichy government had so far failed to provide it. An impoverished, storm-lashed rocky fishing outpost, the French colony had experienced a series of economic slumps in the previous 40 years, interrupted only by a brief boom during the era of American Prohibition, when the islands became a major transshipment point for alcohol from Europe to the United States. When the 18th Amendment was repealed in 1933, the residents of Saint Pierre and Miquelon suddenly found themselves dropped into the Great Depression. The situation worsened after the fall of France, when the Vichy government ordered all fishing vessels to remain in port at Saint Pierre.

The Vichy administrator at Saint Pierre, Baron Gilbert de Bournat, a die-hard supporter of Pétain, faced an impossible situation. On July 12, 1940, in a secret message to Vichy, he warned: “Food situation is critical and worsening steadily.”

In another message, de Bournat warned that a majority of the islands’ residents were considered “active or passive partisans of the de Gaullist movement.” In yet another message he lamented that there had been no mail deliveries from France in four months, while British and Gaullist propaganda was pouring in via British suppliers to the colony.

By December 12, 1941, Saint Pierre and Miquelon had reached a boiling point. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, an ardent advocate of diplomatic relations with neutral Vichy, concluded negotiations with the Pétain regime to guarantee a hands-off approach to French possessions in North America in return for their neutrality. Then, at the last minute, Canadian officials became concerned that pro-Vichy officials on Saint Pierre might be using the island’s powerful radio station to assist the U-boats with coded messages about Allied shipping.

De Gaulle was already prepared to act. He had dispatched Muselier to Canada and Newfoundland (then an independent British dominion) to consult with senior government officials. The French admiral briefed them on de Gaulle’s plan, but it failed to win unanimous support. While British and Newfoundland officials favored the move, Canadian officials were divided. The Roosevelt administration—Hull in particular—adamantly opposed it. Muselier reluctantly prepared to abandon the operation and fly back to London. But just before he boarded the plane on December 17, he received a telegram from de Gaulle:

Our negotiations here [in London] have shown us that we cannot do anything in St. Pierre and Miquelon if we wait for permission from all those who say they are interested. This was to be expected. The only solution is an action of our own initiative.

A day later, British officials told de Gaulle that Canadian officials had decided to take over the radio station on Saint Pierre. The general instantly fired off a second telegram to his naval commander that said: “We know…that the Canadians intend to take over the St. Pierre radio station. Under these conditions…proceed to the rallying of St. Pierre and Miquelon on your own and without saying anything to strangers. I take full responsibility for this operation.”

The liberation of Saint Pierre and Miquelon was on.

To no one’s surprise, the actual invasion of Saint Pierre and Miquelon succeeded without a single shot fired.

Approaching from the north of the harbor entrance in the predawn darkness, Aconit paused alongside Surcouf to take on a landing party of 25 heavily armed sailors. Aboard one of the corvettes was Muselier’s most powerful weapon: Ira Wolfert, a reporter for the New York Times. Muselier wanted the seizure of the islands to make headlines.

As the cruiser submarine guarded the entrance to the harbor, Aconit led the other two corvettes into port. Lookouts on the three vessels reported no activity on shore. Mimosa briefly stopped a small postal vessel heading to Miquelon and then allowed it to pass. A fishing dory was also permitted to continue out to sea.

A local gendarme observed Mimosa tying up to the snow-covered coal pier and approached, followed by an elderly fisherman who, spotting the Free French flags, started cursing the Vichy president. “Pétain, le sacre bleu cochon,

le old goat!” he yelled. Sailors on one of the ships tossed him a mooring line, and as he secured it to the bollard, the fisherman continued, “Vive de Gaulle, at last I can say it. Vive de Gaulle!”

The landing party raced through Saint-Pierre, the capital city of the island, quickly securing the town hall, post office, telegraph station, and radio station as residents began streaming from their homes to cheer. The sailors met no resistance. The island’s 11 gendarmes welcomed the occupiers, surrendering their weapons and offering to help round up suspected Vichy supporters. As sailors marched de Bournat to the Aconit, a growing crowd of islanders taunted the Vichy administrator with shouts of “Vive de Gaulle!” Pausing at the gangplank, de Bournat spun around, silenced the crowd with a glare, and snapped off a crisp “Vive Pétain!”

Wolfert, the only independent eyewitness to the invasion, reported the overall support by the residents for the Free French: “Neat home-made de Gaulle flags that had been kept hidden for a long time broke out,” he wrote in his story for the Times. “Cries of ‘Vive Admiral Muselier!’ and ‘Vive de Gaulle!’ rose in a steady roar as people flung up windows or dashed from their bedrooms in varying stages of undress.”

Within a half-hour of the warships’ arrival, Saint Pierre was in the hands of the Free French.

News of the Free French takeover reached Washington immediately. Learning of the event through a telegram from Maurice Pasquet, the U.S. consul general in Saint Pierre, Secretary of State Hull crashed a meeting between Roosevelt and Churchill at the White House to inform them of de Gaulle’s invasion. While the immediate reaction of the two leaders was reportedly to chuckle and brush off the matter, Hull was livid. He saw the seizure of Saint Pierre and Miquelon as a direct threat to his policy of mutual neutrality with Vichy France.

On Christmas Day, as Muselier was organizing a plebiscite to have the residents of Saint Pierre and Miquelon choose between Vichy and the Free French, Hull condemned the takeover and asked the Canadian government what it was prepared to do to restore Vichy control. His blistering statement contained a phrase that quickly backfired when it became public: “Our preliminary reports show that the action taken by three so-called Free French ships at St. Pierre and Miquelon was an arbitrary action contrary to the agreement of all parties concerned and certainly without the consent of the United States government.” (italics added)

The same day, the New York Times published Wolfert’s story on its front page under banner headlines that for the first time since 1939 referred to the invasion of a country by someone other than the German or Japanese armies. Wolfert’s breathless description of the invasion and Muselier’s speedy organization of a vote by the islanders on their future status quickly drowned out the protest from the U.S. State Department.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

In a subsequent dispatch Wolfert reported that 98 percent of the votes cast in the plebiscite favored the Free French.

In the days after the vote, American public opinion turned against Hull and the State Department. Reactions included a public statement issued by 125 American luminaries, including Carl Sandburg and Helen Keller, urging Roosevelt to halt the State Department’s efforts to return the islands to Vichy control.

The diplomatic tug-of-war over de Gaulle’s invasion went on for more than two weeks as Hull tried to convince Churchill and Canadian prime minister King to evict Muselier and his corvettes from Saint Pierre. Both leaders declined to do so.

Eight days after the takeover, Roosevelt signaled that getting the Free French out of Saint Pierre and Miquelon would be more trouble than it was worth. “I told the Secretary of State,” FDR wrote in a memo, “[that] I thought it inadvisable to resuscitate this question by making a statement; that the French Admiral has already declined to leave St. Pierre-Miquelon; that we cannot afford to send an expedition to bomb him out, and that Sumner Welles [FDR’s policy adviser] could best handle this verbally when he gets to Rio [de Janeiro].” A conference of inter-American governments was scheduled to begin in the Brazilian city in several weeks.

For the next two weeks, diplomats in Washington, Ottawa, and London debated how to ensure the neutrality of Saint Pierre and Miquelon and persuade Muselier to remove his warships from the archipelago. Hull even attempted a conciliatory move when at a news conference he tried to take back his impugnment of the occupation forces. “No insult to the Free French had been intended when the term ‘so called Free French ships’ was employed in the State Department’s statement in connection with the Christmas Eve occupation of St. Pierre and Miquelon,” Hull said. “The ‘so called’ referred to the ships and not to the Free French.” Hull’s explanation didn’t fool anyone.

On January 14 Anthony Eden, Britain’s foreign secretary, met with de Gaulle, having been ordered to tell him the islands must be neutralized under Allied control and without the participation of the Free French. Eden hinted that Roosevelt might send a warship or two to Saint Pierre to force the issue. “What will you do then?” Eden asked de Gaulle. “The Allied ships will stop at the limit of territorial waters,” de Gaulle replied, “and the American admiral will come to lunch with Muselier, who will be delighted.”

Eden continued to press de Gaulle. “But if the cruiser crosses the limit?” he asked. “Our people will summon her to stop in the normal way,” de Gaulle replied. Eden kept pushing. “If she holds on her course?” he asked. “That would be most unfortunate,” de Gaulle replied, “for then our people would have to open fire.”

After returning to London from the Arcadia Conference, on January 22, Churchill summoned de Gaulle for a second meeting with Eden. He proposed a compromise in which Saint Pierre and Miquelon would remain liberated from Vichy but the three Allied governments would publish a joint communiqué on the islands’ neutrality that would satisfy the U.S. State Department. De Gaulle agreed.

Even so, the communiqué was never published. Muselier headed to London on February 28, 1942, leaving behind Alain Savary, a 25-year-old Free French officer, as governor. Baron de Bournat and his German-born wife were repatriated to France with the State Department’s help.

Meanwhile, the Free French corvettes rejoined their Allied comrades on the North Atlantic convoy runs. On December 27, Convoy SC62 departed from Sydney, Cape Breton, for the British Isles with 32 merchant ships. The formation would arrive on January 12 with all but one vessel intact. Escorting the formation from its meeting point south of Newfoundland to the Iceland meeting point were four Canadian warships and the Free French corvettes Alysse and Aconit.

The Free French takeover of Saint Pierre and Miquelon quickly faded from public view. After the Arcadia Conference ended, the United States carried out one of the top agenda items: sending U.S. Army troops to Iceland and Northern Ireland as a symbol of American resolve to get into the war in support of the Allies. But that military action was soon overtaken by a sharp escalation in the Battle of the Atlantic when German U-boats launched concerted attacks against Allied shipping along the U.S. and Canadian east coasts in what was termed Operation Drumbeat.

Liberating Saint Pierre and Miquelon was Muselier’s only operation as commander of the Free French navy. On returning to London, he became embroiled in a struggle with de Gaulle over the leadership of the Free French and was retired.

For most of the sailors who served under Muselier at Saint Pierre, a harsher end came all too soon.

On February 8, 1942, just six weeks after it had left Saint Pierre, corvette Alysse was escorting westbound Convoy ON60 about 420 miles east of Cape Race, Newfoundland, when it was struck by a torpedo from the Type VIIC U-654. The blast killed 36 of the 70 men on board. The corvette was taken under tow but sank soon afterward.

Just 10 days later, the submarine Surcouf sank with all 118 hands when it vanished while traveling west in the Caribbean Sea, en route to the Panama Canal and service in the southwest Pacific. A freighter transiting the area later reported colliding with an unknown underwater object. The wreckage was never located.

Corvette Mimosa’s wartime career came to an abrupt end four months after that. Part of a warship group escorting westbound Convoy ON100, it was torpedoed by the Type IXB U-124 some 600 miles southeast of Cape Farewell. Its commander and all but four members of the 68-man crew perished.

Only corvette Aconit survived the war, and with a combat distinction that put the little warship in the news once more. During the night of March 10–11, 1943, the Free French warship was one of eight escorts for eastbound Convoy HX228 when the 60-ship formation came under attack by a wolf pack of 13 U-boats. In the ensuing melee, the Aconit rammed and sank U-444 on the surface—the sub had already been damaged by a British destroyer—and then located and sank U-432.

For the islanders of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, the return to obscurity was swift, but their brief moment in the international spotlight brought at least one improvement: The Canadian government agreed to give them $80,000 a month from funds that had been impounded from the Vichy government.

In the months after the seizure of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, de Gaulle and the Free French steadily increased in stature—despite Roosevelt’s lingering resentment and Churchill’s occasional fits of pique. Outmaneuvering several other French flag officers for leadership of the Free French, de Gaulle would personify the liberation of Paris upon his entry to the city on August 25, 1944. But he never forgot Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

In 1967, while traveling to Canada on a French navy cruiser, President de Gaulle ordered a stopover at Saint Pierre for an emotional reunion with the French islanders he had freed nearly a quarter-century earlier.