On a rainy summer evening in late August 1962 a group of 13 French and foreign conspirators attempted to assassinate French President Charles de Gaulle. Dubbed the Petit-Clamart attack for the suburban Paris commune in which it occurred, it was one of 31 such attacks on the polarizing French leader during his lifetime. As in the past, de Gaulle emerged unscathed from this latest and deadliest bid—then he commanded it was time to root out and punish the perpetrators.

Change in Algeria

The widespread dissatisfaction with de Gaulle that swept France after World War II was rooted in the nation’s history of colonialism and, more specifically, in the president’s response to French-held Algeria’s bid for independence. France had not been alone in its centuries-long acquisition of foreign “properties,” of course—throughout history every major nation in the world, including the United States, practiced colonialism. But as France had recently learned in the jungles of Indochina, there came a time in which colonialism was no longer viable.

France had occupied Algeria since 1830. In the wake of World War I increasing calls for independence by nationalist Muslims of the North African colony were answered by Paris’ promises of greater autonomy. For decades the promise went unfulfilled. Then, on V-E Day, May 8, 1945, a group of Algerian Muslim protesters organized a demonstration in the provincial capital of Sétif, demanding Algerian independence. The protesters turned violent, exchanging gunfire with police and killing more than 100 Algerian-born European colonists, known as pieds-noirs. The French military immediately responded, killing upward of 1,500 Algerian Muslims.

Nine years later, inspired by France’s defeat in Indochina, Algerian Muslim guerrillas calling themselves the Front de libération nationale (National Liberation Front), or FLN, launched a wave of attacks against military and civilian targets throughout the colony, hoping to force diplomatic recognition of Algeria as a sovereign state. Again, the French army in-country—which reached a peak strength of 470,000 troops—responded, engaging the rebels in a war that lasted more than seven years and claimed upward of a half million lives. The heaviest fighting took place in and around Algiers. Both sides employed torture and terror tactics.

In November 1958, buoyed by the combined support of the pieds-noirs and army officers who had staged a pro-French coup that spring in Algiers, Charles de Gaulle returned to office as president of France in the expectation he would handily put down the ongoing Algerian revolt. Indeed, he virtually swore to maintain France’s hold on the colony. It was, therefore, a stunning blow to pro-French Algerians, as well as many citizens of metropolitan France, when de Gaulle reversed himself in September 1959 and declared for Algerian “self-determination.” True to form, he was being less idealistic than practical. Keenly aware of France’s debacle in Indochina, and unwilling to travel the same road in Algeria, de Gaulle chose to risk the enmity of his officer corps, the pieds-noirs and many of his own citizens by promoting independence for the colony.

In February 1961 a group of high-ranking army officers went underground to form the Organisation de l’armée secrète (Secret Army Organization), or OAS, which began a campaign of terror against Algerian Muslims, hoping to spark violence that would lead to French army intervention. That April the OAS launched an unsuccessful coup in Algiers, hoping to persuade de Gaulle not to abandon the colony. In its wake of that debacle the OAS committed acts of sabotage and assassination in both Algeria and metropolitan France aimed at thwarting the promised turnover. Heading its target list was the French president.

Regardless, on July 1, 1962, Algerians overwhelmingly approved the terms of their independence from France, and two days later de Gaulle pronounced the nation’s sovereignty. The turn of events engendered bitterness and a sense of betrayal among many French citizens, both in Algeria and at home. Most of the million or so pieds-noirs immediately left Algiers, while the cadre of disgruntled army officers continued to plot mayhem. A month later the Petit-Clamart conspirators sprang their ambush on de Gaulle, coming closer to killing the president than had any previous attempts.

Hatching a Plot

Not surprising, the leader of the cell plotting to assassinate de Gaulle was a military officer. A lieutenant colonel in the French air force, Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry was an attractive, affable family man of 34. Referred to in the press as the “French von Braun,” the brilliant Bastien-Thiry was then serving as his service’s principal aviation weaponry engineer.

Bastien-Thiry had excelled at France’s most prestigious schools of higher learning before joining the air force. Ironically, his father had known and been a political supporter of de Gaulle since the 1930s. The son, however, had come to nurse a deep-seated hatred of the president, whom he believed had betrayed not only his country, but also those Algerian Muslims who had faithfully fought for France only to have been abandoned to the dubious mercies of the FLN. “This is truly a genocide,” he declared at his subsequent trial, “perpetrated against Moslems [sic] who had trusted France. This genocide claimed the lives of several tens or hundreds of thousands of victims, killed after having been horribly tortured.”

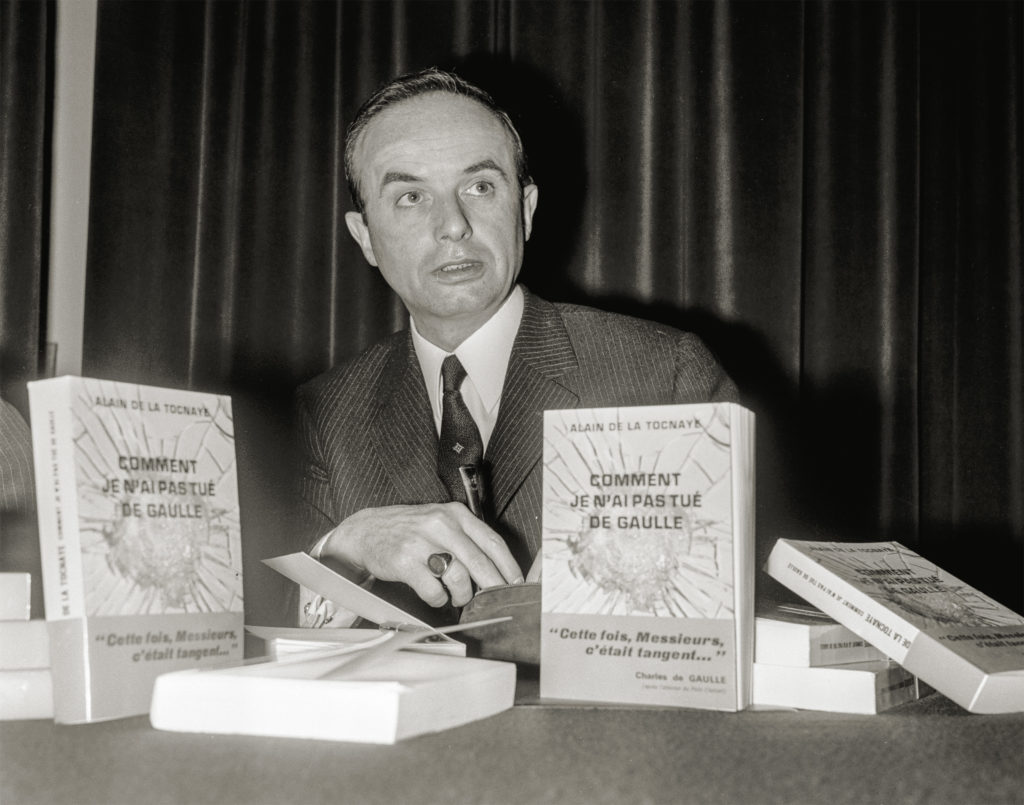

Bastien-Thiry’s lieutenant was 35-year-old Alain de Bougrenet de la Tocnaye. The scion of a noble Breton family, he too was a career military officer—in his case, a French army lieutenant and Algerian War veteran. According to a 1973 New York Times profile of and interview with de la Tocnaye, the disaffected lieutenant was the model for Frederick Forsyth’s title character in the best-selling 1971 novel The Day of the Jackal. But while both the real man and the fictional character shared the objective of assassinating the president of France, the similarity ends there. Where Forsyth’s antihero is “a tall, blond Englishman with opaque gray eyes—a killer at the top of his grisly profession,” de la Tocnaye was “a short, bespectacled, baldish Frenchman with clear blue eyes and the candid, pink‐cheeked face of an aging choirboy.” And where the “Jackal” of fiction was scrupulously secretive, de la Tocnaye was openly verbal in his commitment to kill de Gaulle.

De la Tocnaye had earlier deserted the army and affiliated himself with the OAS in Algiers. Firm in the belief that “political assassination is perfectly normal,” he wrote to de Gaulle, stating in part, “Now that you have betrayed the army and the French people and given away Algeria, the only solution I see left is to kill you, and that is what I propose to do.”

Captured and jailed for desertion in June 1961, the young officer staged a dramatic escape in January 1962. Considering himself something of a romantic hero, he penned a tongue-in-cheek letter to the prison warden that read, “I regret that I could not salute you before leaving, but since my doctor recommended a change of air, I took the first opportunity that came along.”

Bastien-Thiry, for his part, was not a fighting man. He had never been in combat, led troops or fired a weapon, other than at a practice range, nor would he bear arms in the attempted assassination. De la Tocnaye later recalled his first impression of his co-leader: “When I met him, I was surprised. He didn’t look like a colonel, he looked like a librarian. His face was puffy. I wondered what that type of fellow was doing in our type of action.”

Despite their differences, the pair shared the same goals: remove de Gaulle from power, install a military junta in Algiers and restore Algeria as a French possession. Together they set about determining the best method of accomplishing their objectives in one bold stroke. They ultimately decided to ambush de Gaulle’s convoy with automatic weapons.

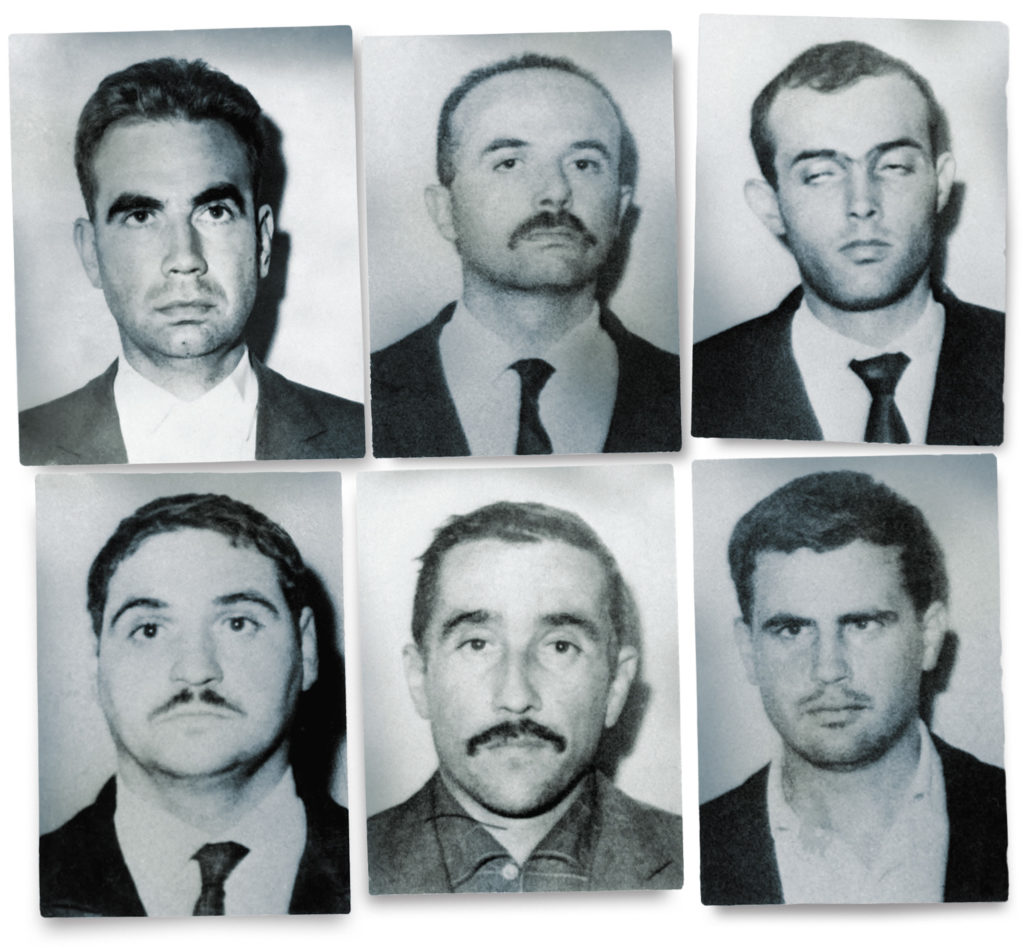

The two recruited a dozen or so volunteers. While most were members of the OAS, joining them were three Hungarians who had fought in their nation’s 1956 uprising against the Soviet occupation and were convinced the assassination of the French president would somehow constitute a blow against international communism. One of the French recruits, a hulking brute of a pied-noir named Georges Watin, had collected the ears of Algerian Muslim rebels he had killed in a glass jar. According to de la Tocnaye, “[Watin’s] fondest wish was to add de Gaulle’s ears to his collection.”

The Plot in Motion

The plot to kill de Gaulle was given the dramatic code name Opération Charlotte Corday, after the French revolutionary who had murdered Jacobin radical Jean-Paul Marat in 1793. While the would-be assassins’ plan seemed feasible, the logistics proved increasingly bedeviling. The OAS failed to provide them the full cooperation they had expected. Promised money somehow never appeared, and in one instance a rival OAS faction stole four automatic weapons earmarked for the operation. Ultimately, most funding came from Bastien‐Thiry’s and de la Tocnaye’s own pockets. The cost of car rentals climbed so high that the conspirators decided to steal the necessary vehicles before the attack.

Finally, all was ready. The plan called for men armed with submachine guns and riding in the backs of two vans to cut off and attack de Gaulle’s convoy in Paris itself. In May and June 1962 the group made 12 attempts to carry out the plan, but either they missed the link-up with the convoy, or there proved to be too many bystanders in the street. Subsequent attempts also fizzled. On one occasion Bastien-Thiry stationed his men along the road leading to a wedding de Gaulle was to attend, only to watch the president arrive by helicopter. In all the conspirators staged 17 unsuccessful “dress rehearsals” in a campaign that resembled more a Keystone Cops routine than a Mission Impossible operation.

Their 18th attempt hinged on the rigid itinerary de Gaulle had established when traveling from his country villa in northeast France to the Élysée Palace in Paris in order to attend cabinet meetings. Since escaping an earlier bombing attack against his car, the president had followed a routine to minimize his time spent on the road. From his Colombey-les-Deux-Églises villa he traveled the 40 miles north by car to a waiting military helicopter at the Saint-Dizier air base. It flew him the 150 miles to the air base in the Parisian commune of Villacoublay, from which a convoy transported him the final 8 miles to the palace.

Bastien-Thiry and de la Tocnaye (code-named “Didier” and “Max,” respectively) set up their ambush in Petit-Clamart, along the road between Paris and Villacoublay. Driving four stolen cars, the would-be assassins were to station themselves at intervals along the road. A source within the Élysée Palace was to phone word of the president’s departure to Bastien-Thiry, who would be waiting in a roadside café. Two primary routes led from the palace to the airport, and de Gaulle never let the chosen one be known until he was underway. Therefore, a member of the cell was to wait for the president’s convoy at a crucial junction, then phone Bastien-Thiry with its chosen path. “Didier” would then emerge from the café and, as the president’s car passed, wave a newspaper to signal “Max” and the other gunmen. As de Gaulle’s convoy approached, the conspirators would block its passage and open fire with automatic weapons.

“This time it was close”

The cabinet meeting on that dank and drizzly August 22 ran long, and de Gaulle did not leave the Élysée Palace until 7:35 p.m. He was seated beside his wife in the rear of the first of two Citroën DS 19 sedans. His son-in-law and aide-de-camp, Col. Alain de Boissieu, sat up front beside the policeman assigned as their driver. Following in the second vehicle were two high-ranking police officials, one of de Gaule’s bodyguards and a military doctor. Escorting the unmarked sedans were two patrolmen on motorcycles. As anticipated, “Didier’s” informant called to let him know of de Gaulle’s departure. Five minutes later the second call came. Emerging from the café, Bastien-Thiry alerted his associates, and the four vehicles drove into position.

As arranged, on catching sight of the president’s car, Bastien-Thiry waved a newspaper. But the conspirators hadn’t anticipated the fading light of dusk. Visibility was poor, and the driver slated to relay the signal, stationed some 200 yards down the road from Bastien-Thiry, failed to see it. The Citroëns’ sudden appearance surprised them all.

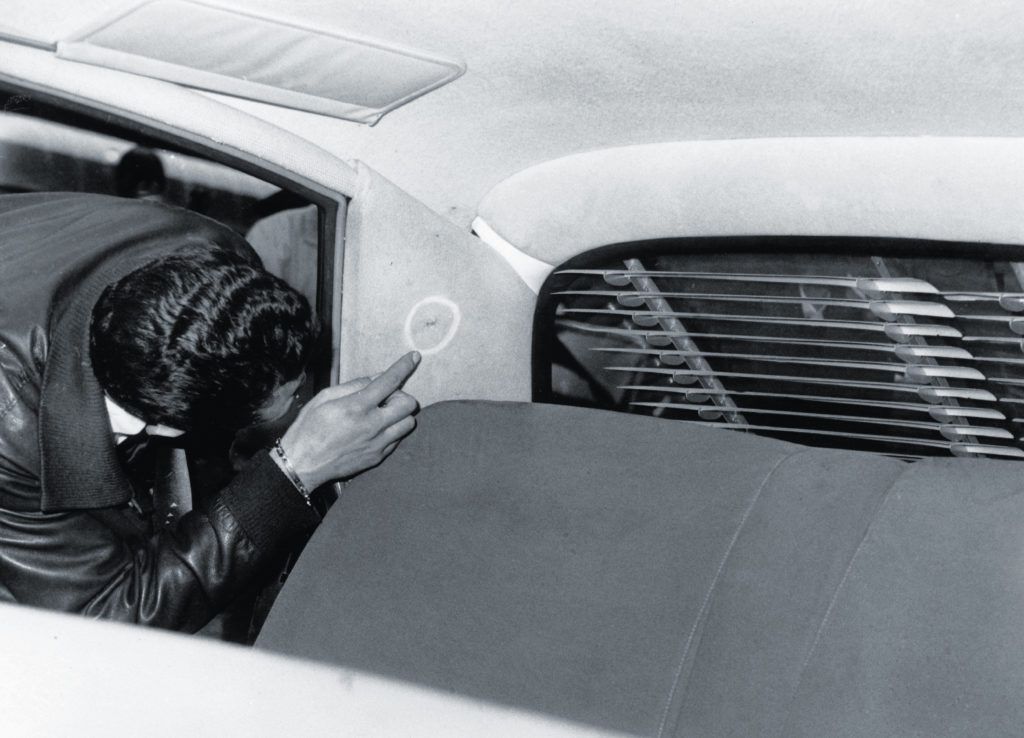

On spotting the convoy, the driver shouted, “Open up!” to the two armed men in his car. They did so, unleashing a torrent of automatic weapons fire toward the president’s car, pouring rounds into the vehicle’s side and tires, as well as into the facades of roadside buildings. De la Tocnaye, tasked with blocking the president’s car with his vehicle, floored the accelerator pedal but was too late to cut off the lead Citroën. As de Gaulle’s vehicle sped off down the road, de la Tocnaye’s passenger, Georges Watin, fired at the rear window of the president’s car, shattering the glass.

Warned by son-in-law Boissieu, de Gaulle and his wife had slumped down in their seats. De la Tocnaye, believing Watin had succeeded, shouted, “You got him!” In fact, none of the president’s party had been hit, nor had any of the townspeople. Considering that investigators recovered 187 shell casings from the scene, it was miraculous that no one had been injured.

Gunning the engine of the lead Citroën, which bore 14 bullet holes in its sides and two tires, the president’s driver sped out of Petit-Clamart and conveyed de Gaulle and his wife safely to the Villacoublay air base. On arrival de Gaulle remarked to those gathered, “Cette fois c’était tangent” (“This time it was close”).

An Emotional Trial

As the presidential convoy roared away the conspirators scattered, having agreed each would make his own way across the border into Spain. Inexplicably, however, most chose to dally in Paris.

Among those on the run was gunman Pierre-Henri Magade, a 22-year-old air force deserter. Stopped at a police checkpoint in early September, he was arrested. Affronted at his contemptuous treatment, he foolishly boasted of his part in the Petit-Clamart attack. Under a promise of partial immunity he then gave up his fellow conspirators, and within two weeks authorities had captured Bastien-Thiry, de la Tocnaye and seven others. Six remained at large, including Watin, the cold-blooded killer who collected ears in a jar and had come the closest to accomplishing the would-be assassins’ objective. (Ultimately fleeing to Paraguay, he died there of a heart attack at age 71 in 1994.)

On Jan. 28, 1963, the nine captured conspirators appeared before the Military Court of Justice in Paris, while the others were tried in absentia. In an emotional trial that captivated France, the defendants called more than 100 witnesses. When de la Tocnaye testified, he took full advantage of his moment in the spotlight, quoting centuries-old writers and delivering a windy diatribe on the current status of France, Algeria and their respective places in Western civilization. De la Tocnaye’s lawyers argued their client’s actions were impelled by honor, as he saw the liberation of Algeria as a betrayal of his military vows to keep the colony a part of France.

Bastien-Thiry took a more aggressive stance, attacking de Gaulle’s government and justifying the act of assassination as a permissible means of deposing a tyrant. He accused de Gaulle of having abandoned to FLN slaughter those Algerian Muslims who had been loyal to France. “The dictator,” he stated, “revealed his monstrous nature in displaying only indifference toward these unspeakable sufferings.”

Yet the young air force officer vigorously insisted his intention all along had been merely to kidnap the president. When the prosecutor asked what he would have done had de Gaulle resisted capture, Bastien-Thiry flippantly replied he would have confiscated the president’s glasses and suspenders. The courtroom was greatly amused; de Gaulle was not. Apparently, the president could pardon an assassin, but he would not tolerate a public insult. Bastien-Thiry’s defense attorney was heard to mutter, “He has just signed his own death warrant,” while one of the military judges later remarked, “He talked too much.”

The trial ran until March 4. Bastien-Thiry was found guilty and sentenced to death, as were five other conspirators, including de la Tocnaye.

De Gaulle later commuted five of the death sentences to life imprisonment. There, however, his leniency ended. There would be no mercy for the disgraced air force colonel. Boissieu later listed his father-in-law’s reasons for having refused clemency for Bastien-Thiry:

• The defendant had directed his subordinates to fire on a car in which an innocent woman, Madame de Gaulle, was present;

• He had endangered civilians traveling in a car near the president’s vehicle;

• He had brought foreigners—the three Hungarians—into the plot;

• While the other conspirators had done the actual shooting, thus exposing themselves to possible return fire, Bastien-Thiry had merely directed events from a safe distance. De Gaulle, the old soldier, saw this as an act of unpardonable cowardice;

• And, finally, there was Bastien-Thiry’s unpardonable “glasses and suspenders” jibe.

“The French need martyrs”

Early on the morning of March 11, a week after the pronouncement of sentence, Bastien-Thiry was awakened in his cell at Fresnes Prison and informed he was about to die. Fearing a riot or a rescue attempt, the government had lined the road from the prison to Fort D’Ivry, the Parisian stronghold at which the execution was to take place, with 2,000 policemen. At 6:42 a.m., as he clutched a rosary, Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry was bound to a post and shot. His was France’s last execution by firing squad.

According to biographer Jean Lacouture, de Gaulle gave a dinner that night for the presidents of the special courts, including the one who had condemned Bastien-Thiry. “The French need martyrs,” he remarked to an old Free French companion. “I gave them Bastien-Thiry. They’ll be able to make a martyr of him. He deserves it.”

In 1968 de la Tocnaye and the other conspirators were included in a general political amnesty and released from prison or pardoned in absentia. (De Gaulle himself retired a year later and died at home of an aneurysm on Nov. 9, 1970, two weeks before his 80th birthday.) After being granted his pardon, de la Tocnaye authored a book whimsically titled Comment je n’ai pas tué de Gaulle (How I Didn’t Kill de Gaulle). When asked during a promotional press conference, “Did you consider when you carried out your operation that Madame de Gaulle was also in the car?” he replied, “She married him for better or for worse, didn’t she?”

De la Tocnaye lived another four decades, dying at age 82 in 2009. As he’d told a New York Times interviewer 36 years earlier, his only regret was “not to have killed de Gaulle.”

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to HistoryNet publications. For further reading he recommends De Gaulle: The Ruler, 1945–1970, by Jean Lacouture, and The Day of the Jackal, by Frederick Forsyth.