In 371 bc a brief and violent battle marked the end of Spartan hegemony in ancient Greece

When asked why he forbade successive Spartan campaigns against the same foes, the legendary Spartan lawgiver and military reformer Lycurgus explained, “So that [the enemy] may not, by becoming accustomed to defending themselves frequently, become skilled in war.” The truth of that statement was borne out in 371 bc on a plain near the central Grecian village of Leuctra, where, after nearly a decade of seesaw conflict, battle-hardened Boeotian yeomen crushed Sparta’s elite peers, ending the latter’s hegemony of Greece.

Following its victory over Athens and its Delian League allies in the 431–404 bc Peloponnesian War, previously anti-imperial and noninterventionist Sparta became both imperialistic and interventionist. In 386 bc Persian King Artaxerxes II, eager to keep his belligerent Greek neighbors in check, reclaimed the buffer regions of Ionia and Cyprus, consolidated his control of the eastern Aegean and imposed a peace on the warring city-states, with the Spartans as his enforcers. Sparta used its status as hegemon, or leading city-state, to bully other city-states into accepting Spartan garrisons and military governors, even attacking some and imposing narrow oligarchies on them.

Thebes, a strong Spartan ally during the Peloponnesian War, suffered under the terms of the peace, which called for the dismantling of its Boeotian League—comprising nearly a dozen sovereign cities and townships. Furthermore, the Spartans installed an oligarchy in Thebes and garrisoned its fortified acropolis of Cadmea. The pro-Spartan government then subdued potential troublemakers, executing some and forcing others into exile, including an

influential soldier-statesman named Pelopidas, who fled to Athens.

In 379 bc Pelopidas secretly returned to Thebes at the head of a dozen exiles. Enlisting the aid of Theban loyalists organized within the city-state by Epaminondas, they assassinated the Theban oligarchs and their supporters and drove off the Spartan garrison. The coup sparked yet another war between Thebes and Sparta, the latter invading Boeotia three times between 379 bc and 372 bc. During these invasions the Thebans chose to fight a guerrilla-style campaign against Sparta’s Lacedaemonian armies, largely avoiding set-piece battles—with one notable exception.

After expelling the Spartans from Thebes, a colleague of Pelopidas and Epaminondas named Gorgidas founded the Sacred Band. The unit comprised 300 homosexual men—150 couples—whom Gorgidas plucked from every social class for their ability and merit. While some contemporary Greeks questioned the emphasis on sexuality in such formations, others thought the men’s emotional bonds made them more resolute warriors. While the origin of the group’s name is uncertain, Plutarch claimed it was because the couples had exchanged vows at a Theban shrine to the mythological hero Iolaus, a nephew and homosexual companion of Hercules. Unlike other Greek hoplites, who were strictly part-time warriors, members of the Sacred Band were full-time professional soldiers like their Spartan enemies. The men spent much of their time training—drilling, wielding weapons, honing their equestrian skills, wrestling and even dancing.

The aforementioned exception to Thebes’ guerrilla campaign against Sparta was the 375 bc Battle of Tegyra, in which the Sacred Band first proved its mettle.

The clash came after Pelopidas set out with the Sacred Band and supporting cavalry to raid the Spartan-allied Theban city-state of Orchomenus. As the raiding party approached its walls, Pelopidas learned of approaching enemy reinforcements. Turning for home, the Thebans ran smack into the superior force of more than 1,000 Lacedaemonians. According to Plutarch, one Theban soldier despaired aloud, “We are fallen into our enemy’s hands!” to which Pelopidas is said to have replied, “And why not they into ours?”

Pelopidas ordered his cavalry forward as the Sacred Band formed into a dense phalanx. When the two armies closed, the band specifically targeted the Spartan field commanders, killing several captains and opening a lane through the enemy ranks. Pelopidas then loosed his men on the Lacedaemonian rear and flanks, shattering the Spartan formation. The Thebans pursued for a short distance, but wary of enemy reinforcements, they quickly re-formed on the battlefield to loot the slain and erect a victory trophy made of captured arms and armor before proudly marching home.

Tegyra was a landmark event, as for the first time in recorded history the Spartans had suffered defeat in a set-piece battle at the hands of a smaller enemy force. By then Pelopidas, Epaminondas and their fellow Thebans had also established a new, more democratic Boeotian League, granting every man, regardless of economic status, the right to vote and to attend the federal assembly.

The new coalition was not without its problems, however. Thebes dominated its ranks, electing four of the seven Boeotarchs, or political-military chiefs. The assembly also met in Thebes, giving its residents disproportionate influence over the proceedings. In addition, league membership was not strictly voluntary, as Thebes stood ready to compel by force the participation of any reluctant Boeotian cities. A few holdouts, like Orchomenus, remained allied with Sparta and garrisoned its troops.

By 371 bc the three major Greek coalitions—Sparta’s Peloponnesian League, the Second Athenian League and Thebes’ Boeotian League—were war-weary. After tough negotiations, they brokered a common peace. But the accord dissolved when it came time to sign and swear to uphold the treaty. Epaminondas initially signed only for Thebes. The next day, however, he demanded to sign on behalf of all Boeotians. The senior Spartan king, Agesilaus II, rejected the power play, insisting Epaminondas spoke only for Thebes, not for the sovereign Boeotian city-states. Agesilaus further warned if Epaminondas did not accept his status, the signatories would exclude both Thebes and Boeotia from the agreement. Epaminondas stood firm. Athens, fearing a strong Boeotian League to its north, disavowed its alliance with Thebes. With Athens on the sidelines, the war between Thebes and Sparta resumed.

Sparta was already in decline by the early 4th century bc. In the century after the 480 bc Battle of Thermopylae the number of homoioi, or peers—the city-state’s elite military caste—had plummeted. While Sparta boasted some 10,000 peers in 480 bc, by 418 bc their ranks had thinned to 3,500 men, and by 394 bc to 2,500. By 371 bc, on the eve of war with Thebes, only 1,000 peers remained. Several factors account for the sharp drop.

The primary reason is that a century of warfare had claimed the lives of many young Spartan men before they had had an opportunity to father children.

Then came the Spartans’ practice of a particularly nasty form of infanticide. While Greeks often left unwanted children—usually girls—outdoors to succumb to the elements, hard-core Spartan elders would inspect male newborns for health and fitness, dooming any not meeting the standard to a cliff dubbed Apothetae (“Place of Rejection”), from which they were hurled to their deaths.

Survivors faced a life of hardship. In the agoge, the harsh school for Spartan boys aged 7 to 19, wards were neglected and often brutalized, some dying of exposure and maltreatment. During one annual ritual, in which youngsters ran a gauntlet of rod-wielding older boys to steal cheeses from an altar, slower boys were sometimes beaten to death. In another test of endurance boys were forced to engage in mass brawls or extended dances under the intense midsummer sun, some dying of heat stroke. Those who lived to see graduation continued to inhabit common barracks and were forbidden to marry until they turned 30.

It was all too easy for a Spartan peer to fall into the disgraced status of a hypomeion (“inferior”). Failure to provide resources for the common mess was one reason, while even a hint of cowardice subjected one to the disgraceful label of “trembler.” Once a man had dropped to inferior status, the system did not afford him a means of reclimbing the social ladder. Thus qualified peers were in short supply when Sparta went to war in the 4th century.

When the tripartite peace talks broke down in 371 bc, an allied Spartan-Peloponnesian army led by King Cleombrotus I—Agesilaus II’s younger co-ruler—was encamped in Phocis, northwest of Boeotia. As soon as he learned the war had restarted, Cleombrotus marched his men along a traditional invasion route north of Mount Helicon through Coronea. But the Thebans, led by Epaminondas and five other Boeotarchs, blocked the way. Withdrawing south, Cleombrotus took his army on a circuitous route over the mountains. En route he encountered and defeated a Boeotian detachment before storming the port of Creusis on the Gulf of Corinth and capturing a dozen Theban warships. Cleombrotus then advanced north on Thebes, a sudden thrust that surprised Theban leaders, who were unaware of the invasion force until it was well within Boeotia. Racing the clock, Epaminondas force-marched the Boeotian League’s army south to meet the threat. The opposing armies met on a plain near Leuctra, a village some 7 miles from the walls of the city-state.

Epaminondas once called Boeotia’s relatively flat and open country “the dancing floor of war.” Leuctra lay on an especially flat plain bound by foothills to the north and south and rivers to the east and west—the perfect field for a hoplite battle. Having carefully chosen his ground, Cleombrotus encamped his army on the foothills south of the plain. The Boeotians arrived later that day and camped in the northern hills.

The allied Spartan-Peloponnesian army—9,000 hoplite heavy infantry, 1,000 peltast light infantry and 1,000 cavalry—was very much a coalition force of “mercenaries with Hieron and the peltasts of the Phocians and the contingents of cavalry from Heraclea and Phlius.” Some 2,300 of the hoplites were Lacedaemonians, and 700 of those were Spartan peers. The commitment of more than two-thirds of its 1,000 peers revealed the seriousness with which Sparta took the campaign.

Facing the Spartans across the plain, the Boeotian army numbered some 6,000 hoplites (including 4,000 Thebans), as well as 1,000 peltasts and 1,500 cavalry. Unlike the singly led Spartan coalition, however, the Boeotians had a divided command structure. Of the seven Boeotarchs, three (Epaminondas, Malgis and Xenocrates) wanted to fight, while three others (Damocleidas, Damophilus and Simangelus) favored a retreat to Thebes to prepare for a siege. The seventh Boeotarch, Brachyllides, arrived late and, after much persuasion by Epaminondas, voted with the hawks, who ultimately persuaded the doves to also stand and fight.

The opposing armies moved into their respective battle formations on the morning of July 6, 371 bc. The Spartans and their allies followed the conventions of Greek warfare. Cleombrotus and his peers comprised the right flank of the hoplite line, with the Spartan-led Lacedaemonians to their immediate left. The other allies stretched out still farther left in decreasing order of skill and reliability. Cleombrotus formed up his heavy infantry 12 deep behind the Lacedaemonian cavalry, the other cavalry units and peltasts on either flank.

The night before battle Pelopidas had a disturbing dream in which the ghost of Scedasus, the father of Leuctrian daughters raped and murdered by passing Spartans, demanded the commander sacrifice an auburn-haired virgin to assure victory for his Boeotians. On waking, Pelopidas consulted his seers and captains about the dream. Some insisted the gods demanded a human sacrifice, while others condemned such outmoded and barbarous practices as abhorrent. In the midst of their debate a roan filly broke from the Boeotian herd, dashed into camp and drew to a halt before them. Pelopidas deemed the horse the offering the gods demanded, and the Thebans duly sacrificed the animal in hopes of victory.

Under Epaminondas’ command the Boeotians reversed their usual formation and placed the Thebans, led by the 300 men of the Sacred Band, in a phalanx 50 men deep on the left, opposite the Spartans. Epaminondas placed the rest of his Boeotian hoplites in an echelon-right formation, ensuring the Thebans would make first contact with the enemy. The Theban cavalry remained masked behind the deep phalanx, while peltasts manned both flanks.

Legend has it before battle Epaminondas came across a large snake and, in view of his assembled troops, crushed its head. “You see that the rest of the body is useless without the head!” he shouted to his men. “In just this way, should we crush this [Spartan] part, the remaining body of the allies would be useless!”

Seeking to avoid combat defections, Epaminondas gave leave to anyone reluctant to fight. A contingent from neighboring Thespiae took him up on the offer. Ironically, their withdrawal opened the battle, for as the Thespians and assorted camp followers moved off, Spartan-allied cavalry and light infantry intercepted them, driving them back into the Boeotian camp.

Cleombrotus then sent his Lacedaemonian cavalry forward, screening an infantry move to flank the massive column ahead of him. But the superior Theban cavalry soon repelled the Spartan horsemen, who backed into their own lines, causing mass confusion among the infantry ranks. The Theban horsemen exploited the chaos by pressing their attack and pushing the weaker Lacedaemonian cavalry entirely from the field.

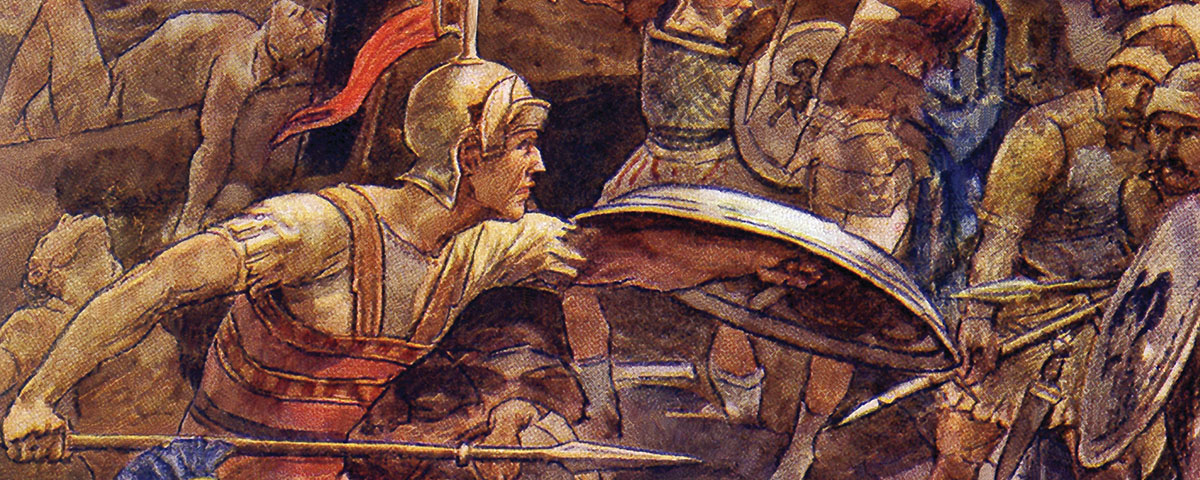

The Theban phalanx then stepped off the line and—unlike the Spartans, who marched into battle slowly and quietly to the music of flutes—came at a run, shouting wildly. The block of hardened Boeotian hoplites, 50 shields deep and 80 wide, soon slammed into the disordered Spartan phalanx, which was only 12 men deep.

Here accounts of the fighting differ. One account claims the Sacred Band was at the leading edge of the Theban phalanx and the first to strike the Spartans. Another suggests the band was on the far left, and once the Theban line made contact with the enemy, Pelopidas led the 300 around the Spartans’ exposed flank.

The Spartans initially managed to hold their line and maintain formation. Then Cleombrotus fell mortally wounded, and Epaminondas called on his Thebans for just one more step to victory. As one Spartan commander after another dropped, their lines began to unravel, and soon the Spartan host broke and ran. During the short, sharp fight the Spartan allies and opposing non-Theban Boeotians, though staring down one another across the plain, never came in contact, ending up mere spectators to the ensuing slaughter.

Later that day the surviving Spartans dispatched the customary herald to the Thebans, seeking permission to recover their dead from the field. The Thebans made them wait until the next day, in the meantime assembling a victory trophy of captured Spartan shields. They also required non-Spartans to recover their dead first, so all could see just how many Spartans lay dead.

Of the 2,300 Lacedaemonians engaged in the battle, at least 1,000 were killed, including 400 of the irreplaceable peers. By contrast the Thebans lost only 300 of 4,000 men. Sometime after the battle the Thebans erected a permanent monument in their city-state—the first to celebrate the victory of Greeks over other Greeks. Restored in the 1960s, it survives today.

Leuctra forever shattered Spartan hegemony. Never again would they lead forces into north or central Greece to impose their will. In fact, over the following nine years it was Thebes that invaded the Spartan homeland four times. During those incursions the Thebans freed Messenian helots enslaved by the Spartans and helped them build a fortified city to keep out their subjugators. Denied the masses of agricultural workers necessary to support the elite warrior class, the whole Spartan system eventually collapsed. Once mighty Sparta was reduced to a military backwater since turned modern-day tourist attraction.

U.S. Army veteran Patrick Baker holds a master’s degree in European history and is a contributor to magazines in Europe and the United States. For further reading he recommends Wars of the Ancient Greeks, by Victor Davis Hanson, and Warfare in the Classic World, by John Warry.