The United States was not kind to the Revolutionary War veterans who had created the new nation. Demobilized troops of the Continental Army received little, if any, back pay due to them. What payment they did collect was typically made in so-called Continental notes, which were of such little value that the phrase “not worth a Continental” entered popular speech. Even the states that had approved the issue of these notes now refused to accept them in payment of taxes. The lot of former officers improved when the confederated government compensated them with new land, mainly in the Ohio country, but enlisted veterans were left in the lurch.

In rural Massachusetts, the veterans were especially hard-pressed. They had not been paid, their crops brought dismal prices in a postwar depression economy, and they were subject to heavy taxation endorsed by the state’s conservative governor, James Bowdoin. The situation was most acute in western Massachusetts, where many citizens felt they had been cheated out of equitable representation by the provisions of the state constitution of 1780. Finding no relief from the state government, these westerners began banding together in a paramilitary movement called “the Regulation.” “Regulators” were groups of 500 to 2,000 men who, armed with clubs and muskets, marched on circuit court sessions with the object of intimidating the magistrates and postponing pending property seizures until the next gubernatorial election which they hoped would see the conservative Bowdoin replaced by a more liberal governor.

For some five months in 1786, Regulators were active in Northampton, Springfield and Worcester as well as smaller towns. Strictly by means of intimidation, they succeeded in keeping the courts closed; no shots were fired and there were no casualties. However, those members of the new national government who favored a strong concentration of federal authority saw the “rebellion” in western Massachusetts as an opportunity to demonstrate the urgent validity of their position. George Washington’s secretary of war, Henry Knox, personally investigated conditions at Springfield where, he believed, the national arsenal was vulnerable.

Knox reported to Congress that the Regulation was indeed a full-scale rebellion led by Daniel Shays, a former captain in the Continental Army, veteran of the battles at Lexington, Bunker Hill, Ticonderoga, Stony Point and Saratoga, and now a struggling yeoman farmer. Knox, who advocated not only a strong central government but also a strong standing army, portrayed Shays’ Rebellion as the work of radicals and anarchists, who wanted to abolish private property, erase all debts and incite a civil war. Knox knew that neither Massachusetts nor the federal government was in a position to finance an army to oppose the Shaysites, so he collaborated with Governor Bowdoin in appealing to Boston merchants to finance a force of 4,400 volunteers under Revolutionary veteran General Benjamin Lincoln.

The rebels were organized into three widely separated regiments, each led by a local figure—Daniel Shays to the east in Palmer, Eli Parson farther north in Chicopee and Luke Day across the Connecticut River in West Springfield. They had planned to attack Springfield on January 25, 1787, but Day had to postpone moving his troops until the 26th. His note telling his fellow rebel commanders that he would be arriving a day later was intercepted. So only two regiments arrived at Springfield late on the afternoon of January 25, marching eight abreast through snow 4 feet deep, led by almost 400 “Old Soldiers,” also veterans of the Revolution.

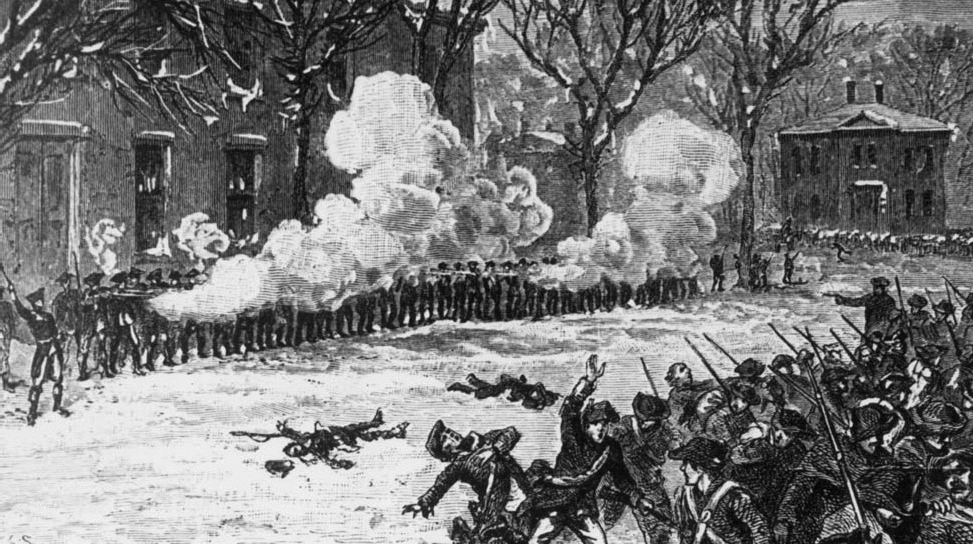

Facing them were 1,200 men under General William Shepherd, who had managed to keep the Springfield militia loyal to Massachusetts. Taking the law into his own hands, Shepherd seized the arsenal to keep it from the rebels. His action was unauthorized and technically illegal, but the powers in Massachusetts were not about to quibble with him. Shepherd deployed several pieces of the arsenal’s artillery, and when 1,500 troops under Shays and Eli Parsons arrived, he fired a cannon into the assembled Regulators. Four were killed—the rebellion’s first casualties—and the raw militiamen in the rear fled, leaving the veteran soldiers alone to face the arsenal’s defenders. Realizing that they were now badly outnumbered, the rebels retreated. The next morning, Lincoln’s army arrived after a long march from Worcester through the deep snow. Lincoln pursued the rebels and decisively defeated them at Petersham on February 4.

Shays and many of the leaders escaped to Vermont, where they were sheltered by Ethan Allen and other prominent Vermonters, possibly including Governor Thomas Chittenden (though he made a point to condemn the rebellion in public). Shays himself was sentenced to death for treason, but the newly elected Massachusetts governor, John Hancock, pardoned him and many other leaders. Only two rebels—John Bly and Charles Rose—were executed. After the breakup of the rebel army, guerrilla warfare ensued, involving a few attacks on wealthy landowners, the freeing of a number of jailed farmers and a good bit of arson. The last known action was fought in South Egremont.

Except for the final encounters, Shays’ Rebellion consisted of a series of peaceful demonstrations against a catastrophic taxation policy during a postwar depression. Knox and other Federalists, however, stirred fears that Shays’ Rebellion was a civil war in the making that would soon spread to all 13 states. Though the rebellion never came close to threatening the stability of the young nation, it greatly alarmed the Founders and provided much of the impetus for them to convene in Philadelphia in May 1787. There they scrapped the weak Articles of Confederation and drew up a new charter mandating a strong central government—the U.S. Constitution.

Originally published in the February 2007 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.