“Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow,” General Hubert Plumer reportedly told his staff, “but we shall certainly change the geography.”

IN THE EARLY MORNING HOURS OF JUNE 7, 1917, ONE OF THE LARGEST NONNUCLEAR EXPLOSIONS in the history of the world erupted along a minor ridge in a tiny corner of Belgium. Ten thousand lives were snuffed out instantly. A gigantic red-and-black plume of smoke and debris blotted out the crescent moon as a shock wave of sound swept for miles in all directions—reaching, by some accounts, as far away as London and Dublin. For the men who detonated this explosion, perhaps the largest in history until an American B-29 dropped an atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, it vindicated years of planning and put an end to months of toil and terror in the mines of Messines.

World War I, replete with so much tragedy, brought some startling innovations. Most of these, such as tanks and new types of aircraft, were designed to break through or circumvent the network of trenches that scarred France and Belgium from the Swiss border to the English Channel. But none enduringly shattered the trench stalemate, and men continued to die in the millions on the Western Front. There seemed to be no way to escape the horrendous casualties from frontal assaults against massed machine guns and artillery.

To British and Dominion soldiers, no place better symbolized the war’s inherent heroism and horror than the Ypres salient. Ypres, an ancient Flemish textile town with a magnificent medieval cloth hall, occupied a sliver of northwestern Belgium that German forces struggled and failed to capture for almost the entire war. While the British held Ypres after barely managing to repulse two major German offensives against the town in 1914 and 1915, their troops inhabited a narrow salient overlooked by the enemy on three sides. German artillery unceasingly pummeled the town and its environs. Reduced to ruins, the cloth hall became an icon of British tenacity. The troops who trudged past it on their way to the front thought of it as a gateway to hell.

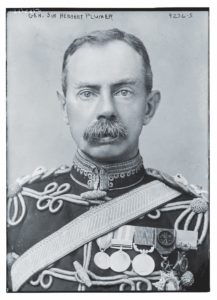

At the beginning of 1917 the British commander in chief, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, aimed to break the German grip on Ypres as a preliminary to a larger offensive designed to aid his hard-pressed French allies and liberate much of occupied Belgium. He entrusted the execution of his plan to General Sir Hubert Plumer, commander of the Second Army that occupied the salient. Philip Gibbs, one of the most famous war correspondents of his day, described Plumer as “almost a caricature of an old-time British general, with his ruddy, pippin-cheeked face, with white hair, and a fierce little mustache, and blue, watery eyes, and a little pot-belly and short legs.” In reality, though, Plumer was a combat-hardened veteran of Britain’s imperial wars who founded his command reputation on precise planning and efficient staff work.

When Haig ordered Plumer to prepare for an offensive at Ypres, he discovered that the rotund little general had anticipated him by several months. Indeed, Plumer had been laying the groundwork for an operation to annihilate the German defenses south of the salient in a single blow. His plan’s success would not rely primarily on planes, tanks, or guns but on a few thousand miners from four nations and nearly 500 tons of explosives.

Military mining dates to ancient times. In the Middle Ages besieging armies dug tunnels to undermine castle walls. As technology developed, they laid and detonated explosives that reduced stonework to rubble. Earthwork field defenses and strongpoints fell victim to the same techniques during the Crimean War of 1853–1856 and the American Civil War, when Union forces detonated mines beneath Confederate works around Vicksburg and Petersburg in 1863 and 1864. But the assaults that followed often failed, typically because of poor timing and coordination by the attacking troops and the ability of the defenders to bring up reserves to plug gaps. In the First World War the British and French were slow to take up mining. The Germans did so with some success in 1914 and 1915, but never systematically.

Plumer’s decision to incorporate military mining into his plan to push the Germans back from Ypres resulted in part from the terrain-related obstacles opposing him. South of the Ypres salient the Germans occupied Messines Ridge. The ridge stretched approximately five miles as the crow flies, from the village of St. Yves (near the town of Messines) in the south to Hill 60, which was just below the salient’s tip in the north. Hill 60, standing nearly 200 feet above sea level, marked the ridge’s highest point. From the ridge the Germans enjoyed commanding views of the entire salient. Naturally, then, they fortified the ridge thoroughly—especially Hill 60—and planned to hold it indefinitely. Attacking infantry, no matter how well supported by artillery, would endure terrific casualties in any attempt to take the ridge, unless some other means were found to eject the German defenders first.

The visionary thinking that this challenge demanded was to be supplied by John Norton-Griffiths, an eccentric Member of Parliament and passionate imperialist known to his fellow lawmakers as “Empire Jack.” Like Plumer he was a veteran of Britain’s imperial conflicts, but Norton-Griffiths also had extensive experience in military and civilian engineering. At the outset of the war he had been supervising a sewer drainage project in Manchester that relied on clay-kicking. In this method, which had also been employed in building London’s Underground, workers braced their backs against tilted wooden boards facing the earth to be excavated. With their feet kicking modified spades, they chipped away at the earth face while an assisting kicker’s mate disposed of the debris behind them. The technique was simple but efficient in heavy clay soil.

Studying the military situation in France and Belgium, Norton-Griffiths quickly surmised that clay-kicking might be used for military purposes. The hidebound British War Office rejected his initial requests to field-test the technique in France, but after the Germans successfully detonated mines beneath British lines at Festubert on December 20, 1914, he was granted an audience with Lord Kitchener, the secretary of state for war. Kitchener at first expressed skepticism, to which the dynamic engineer responded by seizing a shovel from a nearby fire grate, plopping down on the floor, and giving an impromptu demonstration of clay-kicking. Amazed, Kitchener sent Norton-Griffiths to France, where he won over a succession of British generals and was given responsibility for recruiting, assembling, and training several tunneling companies for service on the Western Front.

Even as Norton-Griffiths set to work in the spring of 1915, the first British military mining activities were underway on Turkey’s Gallipoli Peninsula. There, Australian and British troops improvised countermining techniques in response to underground operations by German-trained Turkish forces. Australian tunnelers, recruited from volunteers who had been miners in civilian life, were remarkably adept at subterranean warfare and quickly overpowered the Turks. Their talents would later prove useful at Messines.

Meanwhile, in France and Belgium, Norton-Griffiths had been touring the lines in a battered Rolls-Royce laden with cases of fine Scotch whisky. Touting his War Office authority,

which included the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel, he commandeered experienced miners for his tunneling companies from infantry formations. The cases of Scotch came in handy for soothing the wounded egos of infantry officers. After training in newly established mining schools, Empire Jack’s “moles”—as he preferred to call them—moved to the front, where they quickly made their presence felt in the fall of 1915.

While the British miners proved their worth, Edgeworth David, an Australian geology professor and polar explorer, persuaded authorities in his country to form their own tunneling units in September 1915 with an initial quota of just over 1,300 officers and men. Organized in three companies and recruited from experienced miners and technicians, including veterans of Gallipoli, the Australians arrived in France in May 1916 and were assigned immediately to Flanders. They found the mining of Messines Ridge well underway.

Norton-Griffiths had visited the Ypres salient in July 1915 and scratched out an informal sketch for detonating mines beneath the ridge. British engineering and mining officers subsequently transformed the sketch into a plan that Plumer initiated on a large scale in February 1916. From the beginning his goal was to blow up the entire crest of the ridge by detonating more than two dozen explosives-packed mines beneath every major enemy strongpoint. Two massive charges would target Hill 60.

In pep talks to the tunnelers, Norton-Griffiths suggested that their jobs would be easy. Just dig the mines, pack them with explosives, and return to your dugouts, he told them; after the order comes to trigger the charges, all you will have to do is sit back and watch the Germans “going up” in a grand fireworks display. But the task would be far more difficult, and protracted, than he imagined.

The tunneling companies from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Great Britain that dug toward Messines Ridge in the summer and fall of 1916 quickly discovered the utility of clay-kicking. The thick blue clay of Flanders was exceptionally difficult to work and foiled the tunnel-boring machines available at that time. Clay tunnel walls tended to swell after excavation, hopelessly encasing any large equipment. The alternative was clay-kicking. The Australians, detailed in sections, opened their pits at night to avoid observation, but they made certain everyone else knew who was doing the digging by erecting wooden kangaroos above the entrances to their shafts.

Shafts were dug straight down, to depths of up to 100 feet, before tunnels were pushed forward toward the enemy positions. Men sandbagged the telltale blue clay on removal and dispersed it at night to avoid detection by enemy aircraft. The tunnelers labored in shifts. Clay-kicking was exhausting, and so was the job of shoring up the galleries with wooden boards. Tunnels were prone to flood or collapse, and methane gas built up insidiously. Miners here, as in coal shafts, relied on mice and canaries to provide warning.

Nothing caused more stress, though, than the fear of enemy detection. Work had to be carried on in absolute silence. The scale of the British tunneling was so great, however, that the Germans quickly caught on. They dug their own tunnels—also quietly—to discover and destroy their counterparts. The consequences of discovery could be grim. At times German troops broke suddenly through gallery walls and laid about with serrated knives, spiked maces, and pistols. More often they detonated small explosive charges known as camouflets to wreck galleries, entombing the tunnelers or—more mercifully—killing them outright.

In these aggressive tactics the British and especially the Australians gave as good as they got. They were fortunate to have had superior technology, especially the French–designed geophone. This was similar in appearance to a stethoscope. Listeners wore headpieces with two rubber tubes attached to microphones, which would be placed at various points on the gallery walls to detect enemy picks in action. The location of the enemy activity could then be pinpointed from multiple listening posts via compass and countermeasures taken. Detected and surprised constantly, the Germans soon found themselves losing the subterranean war. The most important British tunnels were pushed forward undetected.

BY THE SUMMER OF 1916 AN ASTONISHING 24,000 MEN WERE TUNNELING FOR THE ALLIES on the Western Front. Mines were being detonated everywhere—so many, in fact, that one exploded every three hours in British sectors alone. The Australians exploded their first mine, a fairly small one, on June 6 near Ypres; but they mostly focused on the larger tunnels being dug into Messines Ridge. By November Canadian tunnelers had finished digging two large mines beneath Hill 60 and packing the chambers with 56,000 kilograms of ammonal explosives and gun cotton. The 1st Australian Tunneling Company took over from there to protect and maintain the charges until detonation. The Australians had no idea when the mines would be blown, and the Germans were working furiously to find them. Although the Canadians had done superb work in digging and charging the mines, the Australians would arguably have the tougher job in shepherding them through to the moment of detonation.

As soon as they entered the sector, the Australians worked aggressively to fend off German mining operations. But their worst nightmare seemed to come true almost immediately, as listeners detected signs of German tunnelers approaching one of the two mine chambers beneath Hill 60. If the Germans got too close, the Australian would have no choice but to evacuate the chamber or explode it prematurely, compromising Plumer’s offensive. There were no safe options for dealing with the threat. The Australians could do nothing and hope the Germans missed the chamber, or they could dig close to the enemy tunnel and explode a camouflet. But the Germans were now so close that the camouflet might also detonate the central mine chamber. Characteristically, the Australians chose the more aggressive option.

As the Australians inched toward the Germans, they used as little noise-deadening wooden propping as possible, even though it increased the chances that their tunnel would collapse on their heads. The closer they got, the more clearly they could hear the Germans’ picks working. Only a shower curtain’s width seemed to separate the two tunnels, and with each strike of a German pick, clods of clay tumbled from the roof onto the dogged Australians. Finally, on December 18, 1916, the tunnels were judged close enough, and the miners carefully packed 1,100 kilograms of explosive at the end of their gallery. The Australians slithered silently out of the gallery, clambered up the shaft, and waited in tense expectation.

The order to blow the camouflet was given at 2 a.m. the following morning. At that moment, according to one account, “a huge tongue of flame leapt skyward from the enemy’s lines, and then all was deadly quiet.” For an instant, the same fear was in every mind: that the primary charge had blown beneath Hill 60. But the explosion was too small; the central chamber was safe. Failing to deduce how close they had come to a crucial discovery, the Germans abandoned their operations at that spot.

Elsewhere beneath Hill 60, the subterranean war would continue for months. Only later did it become apparent how the Australians’ aggressive tactics had paid off. Here and elsewhere around Messines Ridge, the quantity and quality of the human and material resources that Norton-Griffiths and Edgeworth David had secured for their tunnelers simply overwhelmed the Germans. Though the German miners struggled heroically to countermine and blew numerous camouflets, they could not be everywhere at once. And they were overconfident. Each mining success reported to German army commanders led them to conclude that they had decisively thwarted the British. As a result, at a meeting in April 1917, the German generals decided not to redouble their mining efforts but to scale them back.

Plumer was unaware of the German decision but sensed that he was nearly ready. When Haig told him to plan and prepare an offensive for the beginning of 1917, Plumer did so with his customary thoroughness. He detailed three corps, from north to south the X, XI, and II Anzac, to attack the ridge concentrically. Their infantry—including men from Britain, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia—would train exhaustively beforehand so that they could move according to meticulous timetables. Tanks would accompany their assault, while aircraft strafed, bombed, and spotted for the artillery. The big guns would play the most vital role aboveground, saturating the German positions with high explosives and poison gas for several days before the primary assault, and then accompanying the advancing infantry to suppress enemy fire. Everything, though, depended on the mines. They had to be completed and fully primed before the attack could begin.

As winter moved into spring 1917, Haig grew increasingly nervous. The French offensive on the Chemin des Dames that began on April 16 ended during the first week of May in blood-soaked confusion and widespread mutiny among the infantry. Haig was soon receiving cries for help from his allies to take pressure off of their front, even though the British had already attacked the Germans in another offensive near Arras. Most of the mines at Messines Ridge were ready to detonate, but Haig feared that German discovery of even one of them could wreck the whole offensive. He pestered Plumer to attack immediately, but the general held his ground. Nothing, he insisted, could move forward until every element of his plan was in place.

On June 1, finally, the British artillery bombardment began, pummeling the German primary trenches and strongpoints as well as rear areas. The devastation seemed immense, but the infantry knew that this did not necessarily ensure their safety. On the Somme in 1916, the artillery had pounded German trenches for several days until it seemed that not a single enemy soldier survived. But German soldiers who had ridden out the bombardment in their deep dugouts simply returned to their guns and in a single day (July 1, 1916) inflicted 60,000 casualties, including 19,000 dead, on the British. At Messines Ridge in 1917, the mines would be the infantry’s only insurance against wholesale slaughter.

For the Australians, the tension became nearly unbearable. With no way of knowing that the Germans had cut back their countermining operations, the Australians continued to take casualties from camouflets and German artillery that pounded their dugouts. As the final days ticked down, the Australians checked and rechecked their explosives, shored up galleries, and listened for German countermining. Elsewhere along the ridge, so did miners from Britain, Canada, and New Zealand.

The waiting finally ended at 3:10 a.m. on June 7. As nine infantry divisions with about 80,000 men prepared to move forward, officers manning the entrances of 19 tunnels—the total number that had been completed beneath Messines Ridge, some of them just hours earlier—detonated their charges within seconds of one another. At his post 437 yards from Hill 60, Australian captain Oliver Woodward was so nervous that he threw his electric switch too violently, accidentally touching his hand to a live 500-volt pole. As he reeled across his dugout, stunned by the sudden shock, the mines exploded in unison. E. N. Gladden, a British private waiting to attack the strongpoint, later recalled feeling his body suddenly “carried up and down as by the waves of the sea.” As he peered forward, “the earth opened and a large black mass was carried to the sky on pillars of fire, and there seemed to remain suspended for some seconds while the awful red glare lit up the surrounding desolation.” After a few moments, Gladden recalled, the sound “leapt over us like some immense wave.”

Soon the infantry surged forward into smoke and unnerving silence, with nary a rifle fired against them. Atop the ridge the soldiers discovered scenes of utter devastation. Hill 60 had two craters, one 90 yards across and 16 deep and the other 69 yards across and 11 deep. Each crater was surrounded by three-yard-high rims of concrete and debris, including fragments of equipment and men. Here and there a lucky survivor emerged to surrender, but the equivalent of an entire German infantry division had been eliminated in an instant. Messines Ridge was finally in British hands, breaking a major portion of the German grip on the Ypres salient and, in the long run, saving the lives of many Allied soldiers.

Unfortunately, the days that followed dashed some of Plumer and Haig’s hopes. Pushing east from Messines Ridge, the British infantry again encountered well-prepared German defenses and paid the price, with 20,940 casualties before the battle closed on June 14. German casualties were comparable but included more than 7,000 prisoners, many of them stunned into helplessness by the explosions. Although the ridge fell, no breakout took place, and Haig’s next offensive at Ypres—the Battle of Passchendaele, on July 31—became a new byword for futility and slaughter.

The mining of Messines Ridge nevertheless marked an important if fleeting breakthrough in modern military history. The craters are still easily visible. In some places, mines that failed to detonate or were not completed in time lay sleeping below ground, still packed with explosives; a lightning strike detonated one of them in 1955. Hill 60 in particular—the subject of the 2010 movie Beneath Hill 60—has become a testament to the bravery of the Australian tunnelers who ensured victory on that explosive June day in 1917 and to the 335 of them who died during the First World War. MHQ

Edward G. Lengel, a professor at the University of Virginia and director of its Papers of George Washington Project, writes frequently about the World War I era. His most recent book is First Entrepreneur: How George Washington Built His—and the Nation’s—Prosperity (Da Capo Press, 2016).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2017 issue (Vol. 29, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Day the Earth Blew Open