From childhood David Gerald Thomas aspired to be a good chess player, and as a young man in 1974 he played for Lebanon at the 21st Chess Olympiad, in Nice, France. He also wanted to travel, so over a span of four years he checked off Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Asia while “bumming around the planet.” Another of his goals was to become a writer. After launching a software company and writing computer programming manuals, he went on to author well-received books about New Mexico history, including several about the notorious outlaw Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War. Thomas, 75, recently spoke with Wild West about his writing and some of the more interesting figures from the Mesilla Valley.

What prompted you to write about the Mesilla Valley and southern New Mexico?

I moved to Las Cruces in 2002 and quickly became fascinated with the history of Mesilla. I was surprised so little was known about it, and much that was known was false. For example, historians had the story of its founding, the reason and the date it was founded wrong.

So what were the reasons and when was Mesilla founded?

Mesilla was founded March 1, 1850. At the time it was in the United States, as the treaty ending the Mexican War specified that the border between New Mexico and Mexico would be the “traditional” border between Chihuahua and New Mexico, approximately where it is now. The treaty appointed a commission of 50/50 Mexican and American members to survey the exact border. The map attached to the treaty was 40 years out of date and showed El Paso to be 30 miles farther north than it was.

This mistake was well known at the time the treaty was signed. For reasons never explained, American lead commissioner John Russell Bartlett accepted the location, knowing it was wrong. Everyone on his staff objected, as did the U.S. Congress when it learned of Bartlett’s decision.

They fired him. With that decision, immediately Mesilla went into Mexico. Later the Gadsden Purchase moved it back into the United States.

The story repeated by prior historians was that Mesilla was founded after the Mexican War by people who did not want to be Americans. They were founding a Mexican town. That is completely false. Everyone knew it was in the United States when founded, and it was surveyed as an American town. When it moved into Mexico, many left, as they did not want to be Mexicans.

A second myth repeated by historians is that the Gadsden Purchase was signed a second time in the Mesilla Plaza. There is a plaque showing that ceremony in the plaza. Completely false.

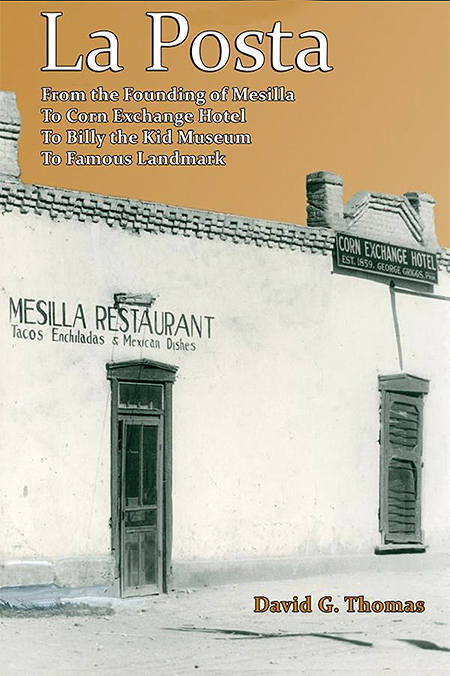

Your first book, La Posta, is about what is now a popular Mexican restaurant. What’s the best thing on the menu?

Your first book, La Posta, is about what is now a popular Mexican restaurant. What’s the best thing on the menu?

Anything with green chile. Enchiladas, posole…When I moved here, I didn’t know the difference between chili and chile.

What about the history of the building and its importance to Mesilla/Las Cruces?

One would think that the first owners of the lots around the Mesilla Plaza would be known. But they were not. In the case of La Posta the first owner was Nestor Varela. In 1862 he sold to Roy and Sam Bean. Roy later became famous as “The Only Law West of the Pecos.” The Beans had their property confiscated by the U.S. government when Mesilla was occupied by Union troops. In 1874 the site became the Corn Exchange Hotel, probably the most famous hotel in New Mexico at the time. The following participants in the Lincoln County War stayed there one or more times: “Doc” Scurlock, Charles Bowdre, Richard Brewer, James Dolan, John Riley, Colonel Albert Fountain, William Rynerson and Judge Warren Bristol.

You next wrote a biography of Giovanni Maria de Agostini. What made you want to write about that well-traveled Italian monk?

When I began researching Agostini, almost nothing was known about him, and almost all that was “known” was wrong, even his real name and birth date. I was able to discover his travels in Europe and South America. I found articles about him in Brazilian newspapers of the 1840s, Mexican newspapers of the 1860s, and such primary documents as passports and police reports. It’s an amazing story. He was a man who combined two seemingly contradictory aspirations: a fervent desire to devote his whole life to “perfect solitude” and an astonishing urge to travel incessantly. He was born in Italy on July 11, 1801. The ruins of the house where he was born still stand. He came from a poor family, not nobility as often asserted. He was murdered April 25, 1869, in the mountains east of Mesilla.

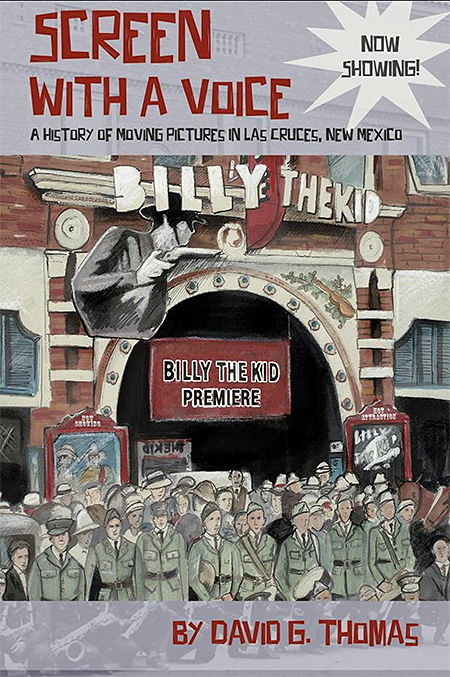

Your next book, Screen With a Voice, covered the motion-picture industry in southern New Mexico. What was the nexus of that project?

Your next book, Screen With a Voice, covered the motion-picture industry in southern New Mexico. What was the nexus of that project?

In 2018 I co-produced with a Brazilian company a documentary about Agostini called The Wonder of the Century, a nickname Agostini was given in Cuba in 1861. We shot in Italy, New Mexico, Mexico, Peru and Brazil. The movie has been released in South America, but not in the United States. One of the most interesting sequences we shot was a festival in Peru in Agostini’s honor that was celebrating its 150th year.

What did you learn about director King Vidor’s 1930 film Billy the Kid?

I write about the movie in Screen With a Voice. The world premiere of Vidor’s movie was Oct. 12, 1930, in the Rio Grande Theatre in Las Cruces. The movie was one of the first talkies. It was based on Walter Noble Burns’ book on Billy and is accurate where Burns is accurate and not when he is not. It has an open ending.

What are some misconceptions about Billy the Kid?

That he was not killed in Fort Sumner by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett. He was.

Does Billy’s headstone in Fort Sumner mark the spot, or were his remains washed away in a flood as some allege?

I believe I prove in my Billy the Kid’s Grave book that his marker is within a few feet of the original burial location, and the grave was not washed away. The evidence is the map made by Charles Dudrow in February 1906. Dudrow was hired to move the military burials from the cemetery. The map shows Billy’s burial location. Dudrow found the military burials undisturbed by the massive Pecos River flood of 1904, which submerged the cemetery under 4 feet of water for seven days. By the way, Garrett visited the cemetery a year after the flood and was able to locate Billy’s grave.

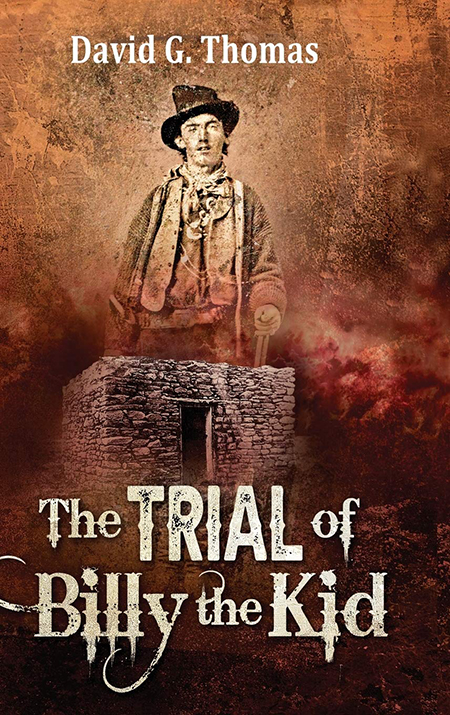

Explain the scarcity of records for Billy’s trial in Mesilla for the murder of Sheriff William J. Brady.

There are several reasons. The records of the trial were sketchy to begin with, and people began stealing them from the files in the 1930s. For this reason I found records in personal collections that were not available elsewhere. There were two Mesilla newspapers at the time. One has many missing issues, and the other was on the verge of collapse. The newspaper that is extant published little on the trial, which is surprising, given the extensive coverage Billy was receiving in the territorial press. The editor of that paper did write he had two interviews with Billy that he would make “public at the proper time.” But shortly after the trial ended, his paper folded. He restarted it later under a different name in El Paso, but he never published the promised interviews. What a loss!

What more did you discover, and how did you find it?

What more did you discover, and how did you find it?

One surprise was that the territory only made it legal to testify in one’s defense 13 months before Billy’s trial. That was a new right, and Billy’s attorney did not use it. I speculate as to why in my book The Trial of Billy the Kid. Another question I was able to answer definitely: Was there a transcript of the trial, and if so what happened to it? Various historians have written there never was a transcript, or that it was lost or stolen. The truth is the laws of the territory mandated a transcript. But if a case was not appealed, then the court did not pay the clerk to make a formal copy for the case file. That was an unnecessary expense for an unappealed case.

Did the Kid receive a fair trial?

The trial was unfair. Judge Warren Bristol manipulated the jury to get the outcome he wanted. First, he only permitted the jury to consider a first-degree murder conviction or an acquittal. The territory recognized five degrees of murder. The appropriate conviction was one of the lesser degrees, given the evidence the territory had. Second, Judge Bristol provided the non–English-speaking jury with deliberation instructions that included spurious instructions designed to confuse the jury. Also, the instructions were given to the jury only in English. It’s doubtful any of the jurors could speak or read English, and many could not read Spanish. Judge Bristol rejected the jury instructions proposed by Billy’s attorney, Colonel [Albert Jennings] Fountain, which, if supplied to the jury, would probably have produced an acquittal.

What have you learned about Pat Garrett’s death?

I am able to prove that “Deacon Jim” Miller did not kill Garrett. My book [Killing Pat Garrett: The Wild West’s Most Famous Lawman—Murder or Self-Defense?] and my article [“He Shot the Sheriff”] in the February 2021 issue of Wild West reveal nine previously unknown facts supporting this statement. I’m able to show that purported killer Miller was in a hotel in Las Cruces when Garrett was killed, and that that fact was known to the jury and attorneys during trial of the man who did kill Garrett—Wayne Brazel. I’m also able to show there was no “Fornoff Report,” the oft-cited evidence of a conspiracy to kill Garrett.

How do you settle on subjects for your nonfiction?

The first [Lincoln County War] topic I began researching was Billy’s trial. From the beginning I collected everything I found on related topics. When going through a collection, I always look at everything. I have been to archives and collections from New York to California. I digitize all documents I get, so they can be found without searching through paper files.

What other Mesilla Valley figures or events would you like to cover?

I’m working on a history of the Shalam Colony, a utopian religious colony founded in 1884 near Mesilla. They had their own sacred book, called Oahspe, which was channeled to the colony founder by automatic typing. It took him 50 weeks to type the 900-page book. The word Oahspe means “earth, sky and all things created” in the language of the spiritual source. The book contains elaborate, amazing drawings of the universe produced by automatic drawing.

Anything else you’d like readers to know?

I would like to call readers’ attention to the Pat Garrett Western Heritage Festival, held annually in Las Cruces in the Rio Grande Theatre. This year the festival will be November 6. The festival consists of movies, original music and a play. Last year the play was the trial of the men charged with killing Colonel Fountain. The prior year it was the trial of Wayne Brazel, charged with killing Garrett. This year the play will be the trial of Billy the Kid. WW