Name the most effective American bombers of World War II and you’ll certainly come up with the B-17, B-24 and B-29, maybe the twin-engine B-25, but how many will think to include the little Douglas SBD Dauntless on the list? The Dauntless dive bomber flew almost entirely over the Pacific, and there it did more to win the war than any other bomber type, even including the Superfort’s two atom bomb missions. Yet of the 35 U.S. types that flew major combat in WWII, none was as old-fashioned and low-tech as the SBD.

Show someone who isn’t an aviation fan photos of a Dauntless and a North American AT-6 trainer, which first flew in 1935, and they won’t be able to tell the difference. The two airplanes are nearly identical in size, shape and detail. With a wingspan half an inch narrower than the AT-6’s, the SBD-5 had exactly twice the trainer’s horsepower and only moderately better performance—40 mph more cruise speed, a 1,300-foot higher ceiling, 500 feet per minute better rate of climb—but the extra grunt gave it the ability to typically carry a 1,200-pound bombload, including a ship-killing half-tonner under the fuselage centerline.

With those bombs, SBDs sank five of Japan’s eight fleet aircraft carriers and a sixth light carrier. The Dauntless played a major role in reducing Japan’s cadre of world-class navy pilots to a bunch of low-time novices left to fling their airplanes and bodies at American ships as kamikazes.

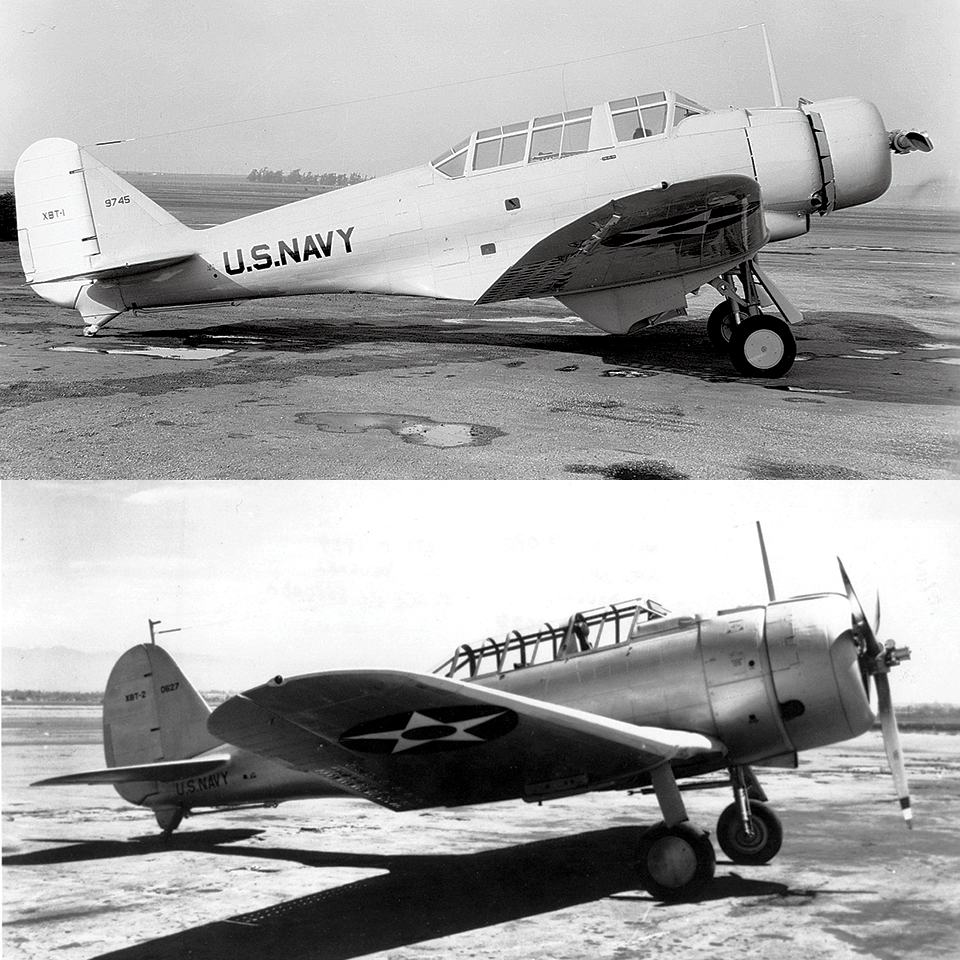

The SBD started out as a Northrop, not a Douglas. Its designer, Ed Heinemann, worked for Jack Northrop, who had developed the sleek, precedential Alpha, Beta and Gamma mailplanes of the late 1920s and early ’30s. Northrop was already producing for the Air Corps the pre-SBD, Gamma-based A-17A dive bomber. Building on this substantial foundation, Heinemann initially came up with the ill-handling Northrop XBT-1 dive bomber of 1936. By the time Donald Douglas took over the Northrop company, Heinemann had fixed its failings and developed the much-improved XBT-2, the direct forerunner of the Dauntless.

The XBT-2 got letterbox wing slots—not leading-edge slots but fixed flow-throughs well aft of the leading edge, mid-chord directly ahead of the ailerons. These slots kept the airflow attached and cured the XBT-1’s nasty stall characteristics. They also helped to create the outstanding lateral-control handling qualities that would make the SBD so effective at precisely altering its aim during a near-vertical dive, as well as its docile behavior during carrier landings. One of Heinemann’s most important accomplishments toward perfecting the Dauntless design was its beautifully balanced controls. When properly trimmed, an SBD’s solid and steady dive, responsive to minor adjustments in every direction, made it a remarkably stable and accurate weapons platform.

Heinemann was one of the most effective warplane designers of the 1940s through the 1960s. In addition to the SBD, he was responsible for the Douglas A-20 and A-26 attack bombers, the AD-1 Skyraider, A3D Skywarrior (the “Whale,” to this day the heaviest aircraft ever produced for routine carrier use) and the A-4 Skyhawk. He also oversaw the creation of the F-16 Viper when he ultimately became vice president of engineering at General Dynamics in the early 1960s.

Heinemann was busy enough with the SBD that he had nothing to do with the clumsy Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bomber, contemptuously nicknamed the “Torpecker.” Its main contribution to the war was to distract the Japanese during the Battle of Midway with its fruitless low-level attacks while SBDs dove on the carriers from above. During one Midway mission, 41 Devastators attacked the Japanese fleet. Thirty-five were shot down and not one scored a successful torpedo hit. (Admittedly, blame had to be shared with their terrible Mark 13 torpedoes, which rarely ran true or exploded on impact.) Meanwhile, SBDs fatally damaged all four Japanese carriers participating in the June 4-5, 1942, battle.

A problem with early fixed-gear dive bombers had been that centerline bombs tended to bobble around in the airstream and bounce off the landing gear immediately after release. (It might seem that dropping a bomb through the prop disc would be a greater problem, but that would have required a steeper dive than what was then being achieved.) The solution was bomb displacement gear, usually called a bomb crutch or yoke—a simple device that swung the released bomb through a 90-degree arc that put it well away from the fuselage before it was fully dropped. Heinemann fitted the fixed-gear Northrop XBT-1 with a bomb yoke and retained it for the Dauntless, which could actually dive steeply enough to put its bomb through the prop.

Despite its antediluvian appearance and low-tech approach, the SBD was slow to achieve squadron service. The first two versions, the SBD-1 and -2, weren’t even war-worthy, since they had neither armor nor self-sealing fuel tanks. The combat-ready SBD-3, the “Speedy Three,” entered service at roughly the same time as the advanced Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

The SBD started its war in the Pacific right on time—on the morning of December 7, 1941—but it was an inauspicious debut. Seven Dauntlesses were shot down or crashed and more were destroyed on the ground, totaling about two dozen lost. Three days later, however, an SBD from the carrier Enterprise sank the submarine I-70 north of Hawaii, scoring the first Japanese fleet sub of the war.

Another early action in which an SBD played a part was Jimmy Doolittle’s April 1942 Tokyo Raid. In its S-for-scouting role, a Dauntless discovered the Japanese picket ship that forced the early launch of Doolittle’s bombers. Though he knew the small boat had spotted him, the SBD pilot was unable to break radio silence and had to fly back to Doolittle’s task force and drop a weighted message on Enterprise’s flight deck.

The SBD-4 gained a 24-volt electrical system, a wider-chord wing with more rounded tips and a Hamilton Standard hydromatic prop. But the SBD-5 became the go-to Dauntless, with 1,200 horsepower rather than the earlier 1,000. An equally important upgrade was a reflector bombsight in place of the previous three-power telescope. The tube-with-an-eyepiece sight was prone to fogging as a Dauntless dove from 15,000 feet through increasingly warm, humid Pacific air, as was the windshield, which in the SBD-5 got a demisting heater. The SBD-6 gained a further 150 hp but was already being replaced by the unloved Curtiss SB2C Helldiver. (One carrier skipper, Captain Joseph “Jocko” Clark of USS Yorktown, refused to allow Helldivers aboard his ship. He demanded SBDs.)

The SBD’s most recognizable feature was its perforated flaps, riddled with 318 precisely tapered and flanged, slightly ovalized three-inch holes. The modification had been suggested by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics when the early XBT-1 prototype revealed serious tail buffeting during dives. The outer horizontal stabilizer reportedly flapped through a two-foot arc, and Heinemann himself, riding as a backseat observer, admitted that it “scared the hell out of me.” The shakes were caused by turbulent vortices tumbling off the flaps, and the holes allowed a carefully calculated amount of air to feed straight aft while the flaps retained the ability to hold the airplane at a safe dive speed.

There were two sets of Dauntless flaps: conventional split flaps that stretched below the wing trailing edge and under the fuselage, and dive flaps, which deployed upward above each wing’s trailing edge. All were perforated. For takeoff and landing, the lower flaps were set. They were also used for diving, but with the additional drag of the upper flaps. The dive flaps were powerful enough that the airplane couldn’t maintain level flight, even under full power, while they were deployed. It was therefore critical that pilots begin retracting the slow-acting hydraulic flaps just before pullout from a dive.

One feature the Dauntless lacked was folding wings, considered indispensable for parking on carriers. But Ed Heinemann wanted the strongest possible wings for an SBD’s typical 5G+ pullouts. No hinges for him. A novel solution to the parking problem was troughs just wide enough for SBD tailwheels, extending out laterally from a carrier’s deck so that a row of Dauntlesses could be parked with their main gear just at the deck’s edge.

The SBD was surprisingly effective in air-to-air combat. During the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea, Dauntlesses shot down more Japanese aircraft—35—than did the accompanying Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters. Throughout the Pacific campaign, SBDs claimed a total of 138 enemy airplanes while themselves falling fewer than 80 times (record-keeping was inexact) to Japanese fighters.

One SBD pilot, Lieutenant Stanley “Swede” Vejtasa, attacked seven Zeros and shot down three of them in a single mission during the Coral Sea battle; the previous day he had participated in the sinking of the Japanese light carrier Shōhō. Cook Cleland, later famous as a Thompson Trophy racer, also was credited with several SBD victories.

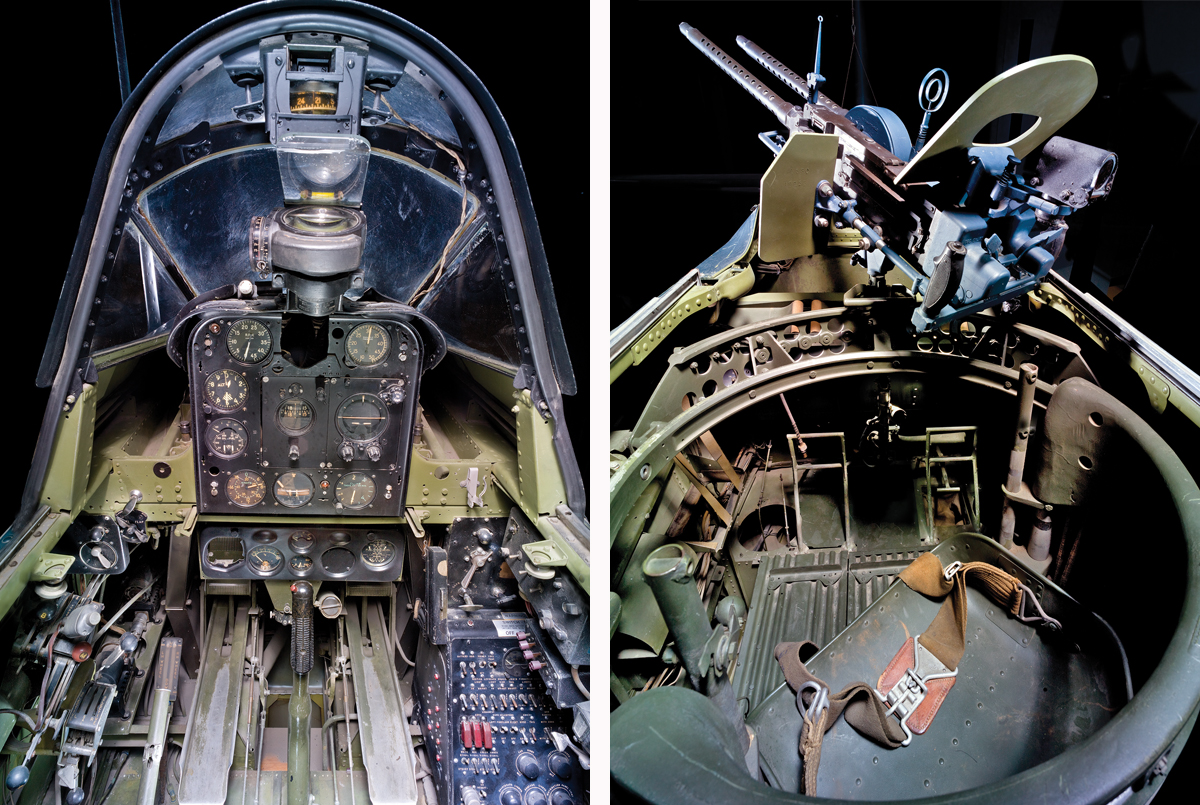

A Dauntless pilot controlled a pair of cowl-mounted .50-caliber guns firing through the prop arc, and the SBD was maneuverable enough to make them an occasional threat. But the most effective guns were the rear-seater’s flexible twin .30s. (Early SBDs had just one tail gun, but it was quickly found to be impotent.) The most notorious Dauntless gunner was Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, who had been a Marine intelligence officer. McCarthy was savvy enough to understand that a combat record, no matter how bogus, would someday play well with voters, so he cadged the occasional local ride in a Dauntless and later parlayed “Tailgunner Joe” into an effective campaign slogan. Never mentioned was the fact that he had once holed his own airplane’s vertical stabilizer with an unskilled burst.

The gunner was also an SBD’s radio operator, and his seat swiveled so he could do double duty. He also had a set of rudimentary flight controls—airspeed indicator and altimeter, throttle and a control stick that could be unclipped from the left cockpit sidewall and dropped into a socket on the floor. He had no way to put the landing gear or tailhook down, but he could at least take a wounded pilot back to the ship and ditch near it.

The Army got its own version of the SBD, the A-24 Banshee, though it was largely unloved. Besotted with their heavy bombers and grand strategic bombing plans, Army Air Forces leaders had no use for dive bombing. They believed intentionally diving a bomber straight toward anti-aircraft defenses at danger-close range was simply a way to put aircrews in harm’s way. They couldn’t make the A-24 work as a level or glide bomber, so they used it as a trainer and utility aircraft.

This despite the fact that the AAF was well aware of the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka’s success against ground targets, particularly armor, during the German army’s 1939-40 Blitzkrieg and the ill-advised Soviet campaign. If there was one airplane that seriously challenged the SBD for the title of world’s best dive bomber, it was the Stuka. But the U.S. Army had few tanks itself at the beginning of WWII and little experience in countering them. During the two prewar decades during which the Navy had practiced and perfected dive bombing, the Army had studiously ignored the tactic.

In fact, AAF leader Henry “Hap” Arnold tried to cancel the initial order for 16 A-24s, claiming the Army had already tested the dive-bombing concept and found it lacking, largely due to a dive bomber’s vulnerability to enemy fighters. Arnold was overruled by General George C. Marshall.

Nonetheless, the AAF taught its A-24 pilots to bomb in a 30-degree “dive,” which was actually a steep glide. The maximum the Army would allow was 45 degrees, which was still glide bombing. Some benighted Army pilots had the brass to call the Banshee “a lousy dive bomber.”

How useful might Army dive bombers have been? One example: At the end of the 1943 Battle of Sicily, German and Italian troops fled across the narrow Strait of Messina to the Italian mainland aboard a shooting gallery of ships and boats. Army fighter bombers flew a total of 1,883 sorties and managed to sink just 13 of them.

After the war, the surviving Banshees became part of the Air Force, which redesignated them F-24s. They remained in service until 1950, well after the last SBDs had been retired.

The British Fleet Air Arm considered using SBDs and tested several of them. Their nicknames for them were “Clunk” and “Barge” rather than “Slow But Deadly.” One of the test pilots, Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown, the most experienced carrier pilot of all time, was underwhelmed by the little Douglas.

“The Dauntless was underpowered, painfully slow, short of range, woefully vulnerable to fighters, and uncomfortable and fatiguing to fly for any length of time, being inherently noisy and drafty,” Brown later wrote. “It was a decidedly prewar aeroplane of obsolescent design and certainly overdue for replacement.” Damning with faint praise, he called the SBD-5’s performance “sedate.”

The Dauntless left Brown baffled. Its performance deficits were so obvious that he deemed it “a very mediocre aeroplane.” Yet he knew its Pacific combat record and could only conclude that the SBD “was among that handful of aeroplanes that have achieved outstanding success against all odds.” (He had only to look to his own Royal Navy’s Fairey Swordfish biplane torpedo bomber, the infamous Stringbag, for another example of such an anomaly.)

If the Dauntless had a secret ingredient, it was that “most important, it was an accurate dive bomber.” Brown found it easy to make precise downline corrections in a dive with the “pleasantly light” ailerons. He also admitted that the Dauntless was hell for stout. “Extremely strong but also rather heavy,” which gave it “a loss rate in the Pacific…lower than that experienced by any other U.S. Navy shipboard aeroplane.” In fact, the Dauntless had the lowest loss rate of any American combat aircraft of the war.

The SBD began to be replaced in November 1943 by the brutish, short-coupled Helldiver—which, in fact, was supposed to have gone into service early enough in the war that the Dauntless would never have been needed. “Events that stick in my memory include every flight I ever made in the SB2C Helldiver,” recalled former Patuxent River test pilot Rear Adm. Paul Holmberg. “We had three to use in testing. Of the three, two had their wings come off.”

The Helldiver’s handling qualities were so bad—much of which could be attributed to the unusually short fuselage—that pilots quickly took to calling it the Beast. The airplane had been intended to trump the SBD in speed, range and weight-carrying ability, yet when it went into service it provided minimal improvements over its predecessor.

The SB2C’s moment of glory came in April 1945, when Helldivers and Grumman Avengers sank the supership Yamato, one of the two heaviest and biggest-gunned battleships ever built. It was the last great dive-bombing feat of any war.

Meanwhile, the SBDs evicted from the fleet continued to fly into 1944 in the hands of the Marine Corps, in support of the island-hopping campaign. They became what Stukas had once been: flying artillery, giving close air support to both Marine and Army troops, particularly in the Philippines. Near-vertical dive bombing was often the only way to bring heavy ordnance to bear against troops in heavily jungled areas. Douglas developed .50-caliber machine gun pods for underwing mounting on SBDs, for dive strafing.

The last SBDs to see action were those of the French navy, flying in 1947 in support of the Indochina War. The SBD-3 was originally intended for export to France, in 1940, but the French order for 174 aircraft was taken over by the U.S. Navy after the country’s fall. The French eventually got the airplane when some 40-plus A-24 Banshees were delivered to Algeria and Morocco in 1943, plus a further 112 SBD-5s and A-24s in 1944. Some of them operated over France after D-Day.

The French removed their Dauntlesses from combat in late 1949, but they continued flying as trainers through 1953. In the U.S. a few civil SBDs operated as photo-mappers, mosquito sprayers and skywriters—one of the last painted in Pepsi-Cola red, white and blue. An SBD even ended up at MGM Studios in Hollywood for use as a wind generator during filming.

One of the world’s most concentrated SBD graveyards is the floor of Lake Michigan, where 38 Dauntlesses were lost in training crashes. Only a few have been recovered, largely because the Navy insists it still owns them. Many of those still on the bottom are particularly rare because they have substantial combat history. After having gone to war, they were superseded by the Helldiver and then sent back to the U.S. for training use.

What was once intended to be a stopgap to await the arrival of a real dive bomber ended up flying through the end of WWII and becoming the most effective carrier-based dive bomber of all time, of all maritime nations. “The SBD’s contribution to winning the Pacific War was unexcelled by any other American or Allied aircraft,” wrote Aviation History contributor Barrett Tillman, the world’s leading Dauntless expert and historian.

As Tillman points out, the Navy got more than its money’s worth. The last SBD-6s cost $29,000 in 1944 dollars (about $425,000 today), less government-supplied equipment such as the engine, instruments, radios and ordnance. Call it a Slow But Deadly bargain.

For further reading, contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends: The Dauntless Dive Bomber of World War Two, by Barrett Tillman; SBD Dauntless: Douglas’s US Navy and Marine Corps Dive-Bomber in World War II, by David Doyle; and Douglas SBD Dauntless, by Peter C. Smith.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!