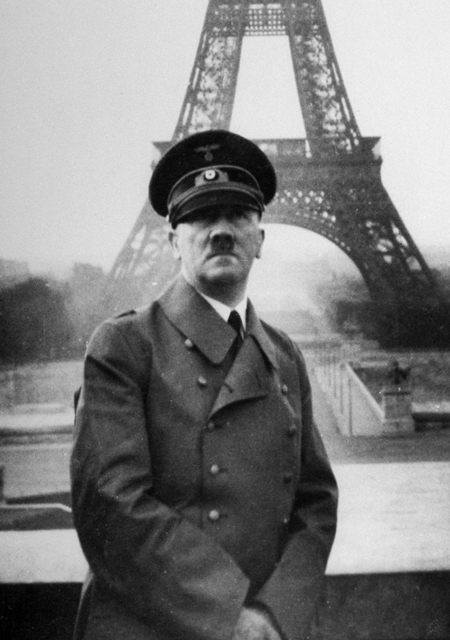

Adolf Hitler visited Paris only once. He landed at 5:30 a.m. on June 23, 1940. By 9 a.m. he had quick-marched his party by the Champs- Élysées, Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe, Les Invalides, and the Panthéon. The Catacombs, snaking for nearly 190 miles beneath his feet, went unseen. Three months later, early partisan groups were morphing this ossuary maze into courier routes, caches, and hideouts.

In 2009, I was back in Paris for maybe the 10th time, and the Catacombs were high on my list to revisit. In 1785, these Roman quarries and beer cellars were converted into mass graves because the overcrowded medieval cemetery in the city’s heart at Les Halles was leaching toxins into Paris’s well water. So night after night for three years, some six million bodies were wheeled in huge carts to new underground homes. No one’s parts remained together—not Rabelais, Danton, Robespierre, or Molière. Sorted into femurs, skulls, and so on, bones were artfully heaped into macabre décor—including one heart-shaped arrangement—that still lines the narrow, winding tunnels, punctuated with tombstones and signage. Parisians, including the future Charles X and court ladies, immediately flocked to see them. In 1860, Napoleon III toured them. Otto von Bismarck came in 1867. Three years later, these two ignited the Franco-Prussian War. Paris was besieged and shelled, its population reduced to eating rats, its final vain defense from this very labyrinth. The victorious Prussians consolidated the Second Reich, Hitler’s precursor. For me, ironies like these are part of what make Paris Paris.

Like all great international cities, this glittering capital of the arts, education, and cuisine is a study in change and paradox: dire poverty and sleek wealth, savoir-faire and angst, absolute monarchs and rebellious peasants, l’amour toujours and the cynical Gallic shrug. Paris regularly explodes into political and cultural turmoil because its multiple personalities manage to coexist until, for reasons that can be sublime or ridiculous, they don’t.

On Mardi Gras 1229, a student brawl about a bar bill escalated until the University of Paris shut down for two years. That initiated the Left Bank tradition of popular protest. In 1968, student riots there swelled, abetted by unions, Socialists, and Communists, and led to President Charles De Gaulle’s resignation.

A generation before, these same groups powered the Parisian Resistance. De Gaulle, in exile in London and struggling to cement his leadership of Free France, pressed to marginalize or control any factions at ideological odds with him. Churchill used FDR’s distrust of these factions to persuade the president to grudgingly endorse De Gaulle and agree that the Free French should spearhead Paris’s liberation.

Most Parisians see the anti-Nazi Resistance as part of the glorious tradition that includes storming the Bastille in 1789, and sending the restored Bourbon monarchy packing in 1830. Yet it is also partly myth—created by De Gaulle, among others, to heal France’s bitter prewar and wartime divisions. The ongoing arguments over the movement’s size, goals, efficacy, and behavior underscore occupied Paris’s tangled history.

When the Wehrmacht rolled in on June 14, 1940, more than half of Paris’s five million people had fled. By 1942, every German intelligence and police agency had headquarters there, with unlimited power and thousands of informers. But Paris was also a Nazi safety valve. Military personnel on leave or occupation duty, industrialists and diplomats on “official” business, and party paladins could relish decadent pleasures the Reich condemned.

Deputy führer Hermann Göring dined at Maxim’s, stayed at the Ritz’s Imperial Suite, and confiscated French art to ship home. His hotel windows faced Place Vendôme and the monumental column Napoleon erected there to honor his 1805 victory at Austerlitz.

Deputy führer Hermann Göring dined at Maxim’s, stayed at the Ritz’s Imperial Suite, and confiscated French art to ship home. His hotel windows faced Place Vendôme and the monumental column Napoleon erected there to honor his 1805 victory at Austerlitz.

When Hitler toured Paris he had lingered at Napoleon’s tomb at Les Invalides. “It was the dream of my life,” he told Albert Speer, who had joined him, “to be permitted to see Paris.” He added, “I often considered whether we would not have to destroy it.” He would again, I thought one afternoon as I crossed the Île de la Cité past Notre Dame Cathedral and ducked into the Préfecture de Police courtyard. Is Paris Burning?, a history of 1944 Paris, came to mind because a plaque there commemorates a key event in the book: the police mutiny on August 19.

Until then the cops generally did the Nazis’ bidding, often with relish. On July 16, 1942, they rounded up 12,884 Jews and brutally separated families. Destination: Auschwitz. The naked cruelty and collaboration shocked and angered many Parisians. Most were just trying to get along, like most Europeans under the Nazi yoke. But this stoked the Resistance. Growing hunger, oppression, desperation, disgust, and hope fanned it. By 1944, Paris had some 20,000 partisans, many working with Churchill’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) to sabotage the Germans, provide intelligence, and aid downed Allied pilots.

I hit the Left Bank, and climbed Rue St. Jacques through the Latin Quarter. When I reached the 13th-century Collège de France and 16th-century Sorbonne, the Île-de-France, the Seine, and the Right Bank rose into stunning view as the slope dropped behind me. I felt grateful that the Nazi governor of Paris, General Dietrich von Choltitz, evaded Hitler’s 1944 orders to leave the city “a field of ruins,” and that Paris had no strategic targets the Allies deemed worth bombing.

Then I was at the Panthéon, perched atop Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. Only those whom parliament designates National Heroes are buried here—Voltaire, Rousseau, Victor Hugo, the Curies, Louis Braille among them.

Here, too, lies Resistance hero Jean Moulin. In 1940, he was tortured for refusing to cooperate with les boches. A year later he traveled to London with fake papers and met with De Gaulle. The tall, imperious exile, trying to extend his authority over anti-Nazi activities, wanted Moulin to unify them. Moulin parachuted into France and set to work. On May 27, 1943, the Conseil National de la Résistance—eight major partisan factions—met for the first time, in Paris, under Moulin’s chairmanship. But his triumph was short lived. Less than a month later, he was arrested, tortured by Klaus Barbie, and died.

One brisk morning, I strolled across the Tuileries Gardens, where German infantry drilled, toward Jeu de Paume, where I used to gawk at Impressionist masterpieces. (These are now at Musée d’Orsay.) Here the Germans gathered French art they plundered—tens of thousands of pieces—before shipment to Deutschland. Rose Valland, the museum overseer and a Resistance member, ran risks daily to keep meticulous records of what was sent where. That eventually helped agencies like the U.S. Army’s “Monuments Men” repatriate nearly all of it.

Nearby Place de la Concorde has wall plaques commemorating Resistance and Free French army members who died liberating Paris. That tale, like so many here, has almost as many spins as tellers.

Eisenhower, reneging on the earlier Allied agreements about taking Paris, decided to avoid it. It presented a logistical nightmare. Keeping Allied troops supplied without a port was taxing enough. Paris would mean millions of mouths to feed.

With the Allies near, railroad workers shut Paris down on August 18, 1944. Then the police and partisans took over some key buildings. Armed with motley light weapons and using cobblestones to create barricades, they were no match for German tanks and artillery—and they knew it. Thanks to the mediation of a Swedish diplomat, and to General Choltitz’s forbearance, a fragile truce saved Paris from a massacre as well as burning. Meanwhile, a stream of Resis-tance messages to the Allies insisted Paris was theirs for the taking.

With the Allies near, railroad workers shut Paris down on August 18, 1944. Then the police and partisans took over some key buildings. Armed with motley light weapons and using cobblestones to create barricades, they were no match for German tanks and artillery—and they knew it. Thanks to the mediation of a Swedish diplomat, and to General Choltitz’s forbearance, a fragile truce saved Paris from a massacre as well as burning. Meanwhile, a stream of Resis-tance messages to the Allies insisted Paris was theirs for the taking.

The uprising’s leader was Henri Rol-Tanguy, a Communist. From his lair in the Catacombs, he had dueled with De Gaulle for nearly two years over control of the Resistance. De Gaulle knew well the age-old adage, “He who controls Paris controls France.” But he couldn’t budge Ike when he met with him on August 21. So De Gaulle sent a note threatening to order Free French General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque’s 2nd French Armored Division to Paris anyway. The Combined Chiefs of Staff told Ike they didn’t object; the Allies would recognize De Gaulle’s provisional government as France’s. Restoring France’s self-respect and keeping it out of Stalin’s bloc were vital.

The day after Liberation, De Gaulle led a million jubilant Parisians down the Champs-Élysées to sporadic German sniper fire. Reprisals against collaborators, from shaving women’s heads to summary executions, began. Innocents suffered with the guilty. The war in Paris was never clear cut.

In 1940, Hitler’s final stop in Paris had been Sacré Coeur, the basilica atop the highest hill in Montmartre, the populist quarter the Impressionists loved. After-ward, Hitler turned to Speer: “Wasn’t Paris beautiful? But Berlin must be made far more beautiful. When we are finished, Paris will be but a shadow. Why should we destroy it?” Yet in 1944, faced with its loss, he screamed for its destruction. Sixty-five years later, I stood on the cathedral’s plaza and gazed across the City of Light, remembering Casablanca: “We’ll always have Paris.” And I laughed.

Gene Santoro is the reviews editor for World War II and American History magazines, and covers pop culture for the New York Daily News. His latest books are Highway 61 Revisited and Myself When I Am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus. His current project deals with U.S. State Department cultural tours. He began to appreciate the ironies of Parisian history and culture in 1978, when he spent a month living on the Left Bank.