In their 2019 book Scholars of Mayhem Daniel C. Guiet and Timothy K. Smith relate the fascinating story of how Guiet’s French-born American father, Jean-Claude Guiet (1924–2013), went from being a sheltered freshman at Harvard to become a highly trained and immensely successful World War II covert operative for both the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE). One of four SOE agents dropped into German-occupied France in 1944, the elder Guiet started his clandestine career as a radio operator but was soon conducting ambushes, blowing up vital installations and helping prevent a crack Waffen SS armored unit from reaching the Allied beachhead in Normandy.

How did your French-born father end up in the U.S. Army and Britain’s SOE?

My grandparents René and Jeanne met as exchange students from France while studying at the University of Illinois after World War I. They married, had a son named Pierre and moved back to France before my father, Jean-Claude, was born. The family ultimately returned to America, where René and Jeanne became professors in the French department at Smith College in Massachusetts. My father and his older brother grew up bilingual, and they and their parents spent summers in France.

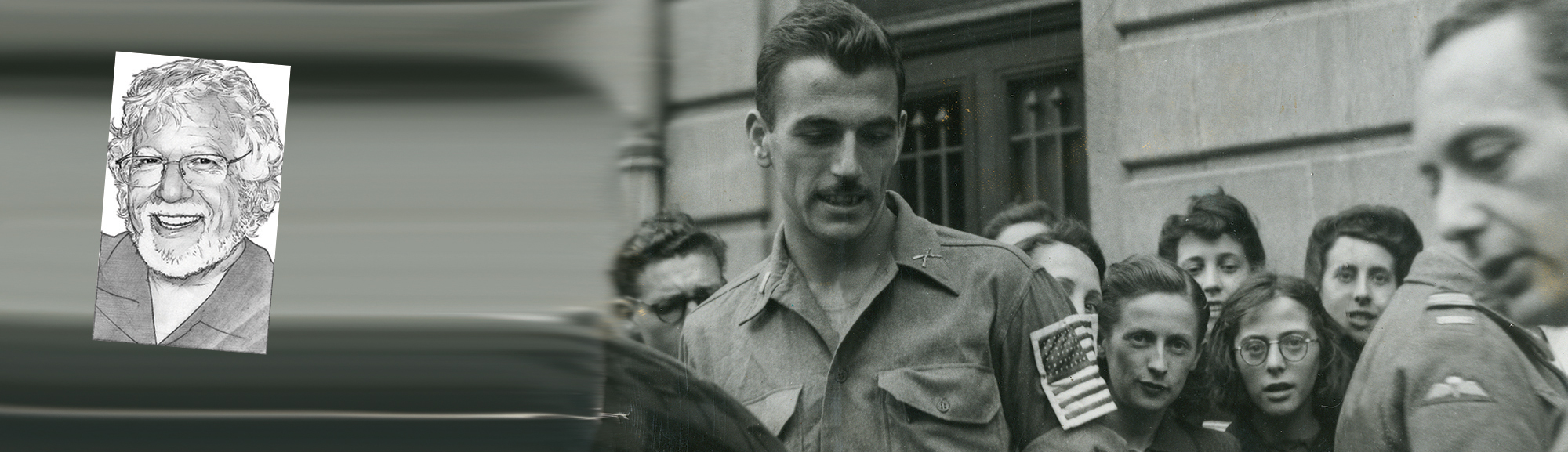

In 1943, when my father was a freshman at Harvard, he received a draft notice. While undergoing basic training in South Carolina, he was granted U.S. citizenship and also interviewed by an officer who tested his French fluency. After basic training Jean-Claude volunteered for parachute school but had only been at Fort Bragg, N.C., for a few days when pulled out of the course and sent to Washington, D.C., where he was told he would be joining the Office of Strategic Services—though at the time he didn’t really know what the OSS was.

My father underwent training in Virginia, where he ran into his brother, who had also been tapped for OSS duty. Jean-Claude was taught a range of specialized skills—shooting, unarmed combat and guerrilla tactics—as well as Morse code and covert communications. On graduation he was sent to England, where the OSS “loaned” him to SOE’s French section. After completing advanced commando training and a parachute course, he joined three other agents—including a woman named Violette Szabo—who on the night of June 7, 1944, were dropped into the Limousin region of south-central France.

‘My father and the others were tasked to create chaos among the Germans and their French collaborators—to kill and maim, gather intelligence and generally spread fear and doubt within enemy ranks’

What was the primary mission of your father’s SOE network after D-Day?

Their orders were to organize anti-German French individuals and existing Resistance groups into a civilian army. The agents were to train, equip and supply that force so it could weaken the 2nd SS Panzer Division, Das Reich, and prevent it from racing to the Normandy invasion beaches with enough armored power to push the Allies back into the sea. My father and the others were also tasked to create chaos among the Germans and their French collaborators—to kill and maim, gather intelligence and generally spread fear and doubt within enemy ranks.

Did your father have any close calls with the Germans?

He certainly did. As the team’s radio operator he encoded and decoded all communications and was therefore a prime target of the Germans’ highly sophisticated radio-tracking efforts. The Germans were so good, as a matter of fact, that the average life expectancy of an SOE radio operator in occupied France was just six weeks.

A small plane that could have been an enemy daily courier flight to Limoges or a flight searching out exact locations of my father’s wireless transmitter routinely overflew the terrain on which he was operating. Twice he was forced to flee his hideout by jumping through a window as Nazi troops crashed through the front door; he barely escaped and hid in the bush. My father was stopped, searched and questioned multiple times while moving about using the documents forged for him by SOE. It often happened when he was returning at sunrise after a long night supervising an airdrop of supplies and weapons.

Once, my father was walking down an isolated dirt road with his teammate Bob Maloubier when they heard enemy trucks approaching. The two of them ran into the heavy roadside foliage and covered themselves up. The trucks stopped less than 50 feet away and troops dismounted. The soldiers stretched, lit cigarettes, and a few walked close to where the two agents were hiding. My father and Bob thought they had been seen and were about to be seized, but instead the troops relieved themselves and then got back in the truck and left. The two SOE men laughed nervously and then raced back to their camp to arrange an ambush of the trucks.

Did your father see combat against the enemy?

Because of his importance as the team’s radio operator, during the early weeks of the mission my father remained hidden, protected by three grizzled Spanish Republican fighters. But because the female member of the team, Szabo, had been captured just three days after the team dropped into France, in early July 1944, Jean-Claude began undertaking riskier duties.

During the following three months he became an active guerrilla fighter and organizer, leading ambushes, participating in numerous firefights, scouting through enemy-held territory and undertaking demolition missions. In late July a German operation to finally clear the Resistance from the region resulted in a series of large, ongoing battles. At one point my father became the de facto leader of a group of more than 500 fighters holding a fixed position against many well-armed veteran troops. The intense fighting lasted for three days. For his courageous leadership my father was later awarded the Silver Star.

How did you come to learn of your father’s clandestine World War II service?

My father signed the [British] Official Secrets Act as an 18-year-old. He took the oath seriously and was skilled at deflecting direct questions about his wartime experiences. When I was 15, dad allowed he’d had some association with the French Resistance. Very rarely, in isolated conversations, he would let slip a random reference that added to my incomplete mosaic.

In 1994 I gave my father a laptop computer for his 70th birthday and begged him to write a memoir about his childhood in France. He initially resisted, saying his life was boring and would be of little interest to anyone. I kept suggesting he write his story just for the family, and a few days later he began writing. My mother quickly learned to resent his compulsive focus on “that damn machine,” as she referred to the computer. My father would periodically hand me a stack of backup disks to hold for him, which he asked me not to look at—a request I honored. When he completed the memoir, which he titled My Lovely Little War, he gave my sister and me a copy.

The event that really opened the floodgates of his story was a phone call I received in 1998 from a woman in England. Rosemary Rigby said she was a founder and owner of a museum honoring Violette Szabo and was attempting to track down Jean-Claude Guiet. I said he was my father and listened in amazement as Rosemary provided a thumbnail sketch of the history of my father’s four-person team, which formed the nucleus of what was known as the Salesman II circuit.

Did your father reconnect with any of his wartime colleagues?

He did. My wife and I took him to the opening of the Violette Szabo Museum near Hereford, England, in June 2000. Among those attending the event was Leo Marks, SOE’s head cryptographer. Until that moment the two had never met, other than through coded Morse messages. The meeting was emotional, and the conversation fascinating. The admiration between the two was palpable.

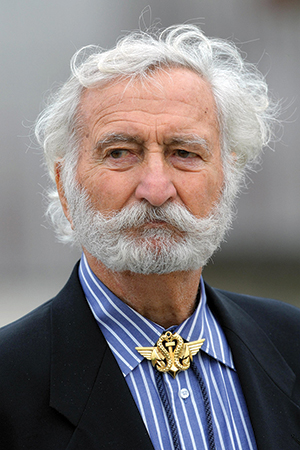

My father’s sole surviving teammate, Bob Maloubier, was also in attendance. The last time they had spoken was in a recently liberated Paris in 1944. Their reunion lasted over the course of five days, during which we listened, learned and questioned. They revisited times and memories neither had spoken of for nearly 60 years. A week later Bob flew his plane from Paris to my home in Jura, France, for further discussions in assured privacy. What ensued were far-ranging and unreserved conversations between the two veteran secret agents, covering their respective long careers. I was fortunate to have additional meetings and numerous interactions with Bob.

In 2001 we flew my parents to France for a week in and near Limoges. We visited the isolated village into which the team had parachuted, as well as old ambush sites and drop zones. We discovered a few French Resistance survivors, who after extensive questioning remembered the “young American wireless operator” who’d fought side by side with them. They phoned others, who rushed to join us, and the day became a celebration and a memorial.

Why did you decide to write Scholars of Mayhem?

The book complements and expands on the story in my father’s memoir [published in 2016 as Dead on Time] with facts that came to light after it was finished. We enriched the memoir, incorporating details from numerous individuals and sources, additional specifics that came to my father as more memories opened to him, and from the extensive research I did in OSS and SOE files that began to be declassified in 1998. Those files and others provided context and insights not available to my father when he wrote the memoir.

By expanding on that account—through declassified original source documents, personal interviews and by visiting the actual sites—we are able to provide an in-depth look at the operations of one SOE clandestine team in occupied France. We incorporate a broad historical framework of those dark times, and we introduce readers to key individuals and their backgrounds. The result is a chronicle of the beginning of a young man’s clandestine life and a detailed history of a critically important group of covert operatives whose combined efforts helped to bring about the Allied victory in Europe.

What are some lasting lessons your father taught you?

Operate independently. Read extensively. Travel. Explore. When in doubt, trust in long-existing clichés, because they exist for a reason. Strive for perfection. Be a keen observer. MH