Thirty-two-year-old Cyrus Walker isn’t your typical Western artist. For one thing, he draws his inspiration from the classic comic books of the 1940s and ’50s. For another, he was born and raised in small-town Vermont—“Nothing but dairy cows and green mountains,” he recalls. And though he majored in graphic design and marketing at Montana State University, for a while he seriously considered pursuing life as a “ski bum.”

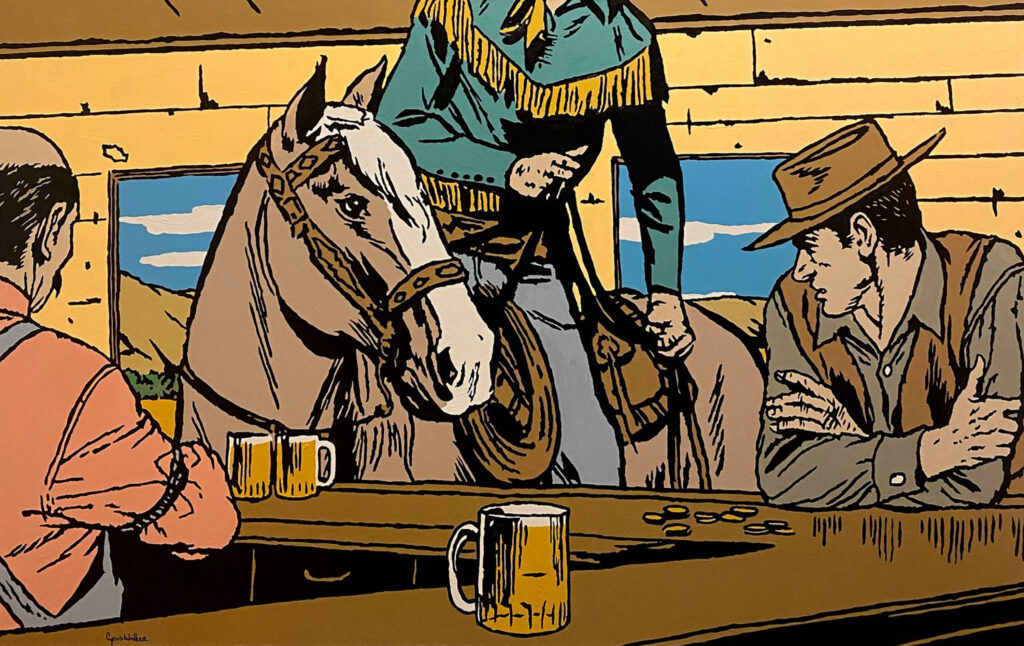

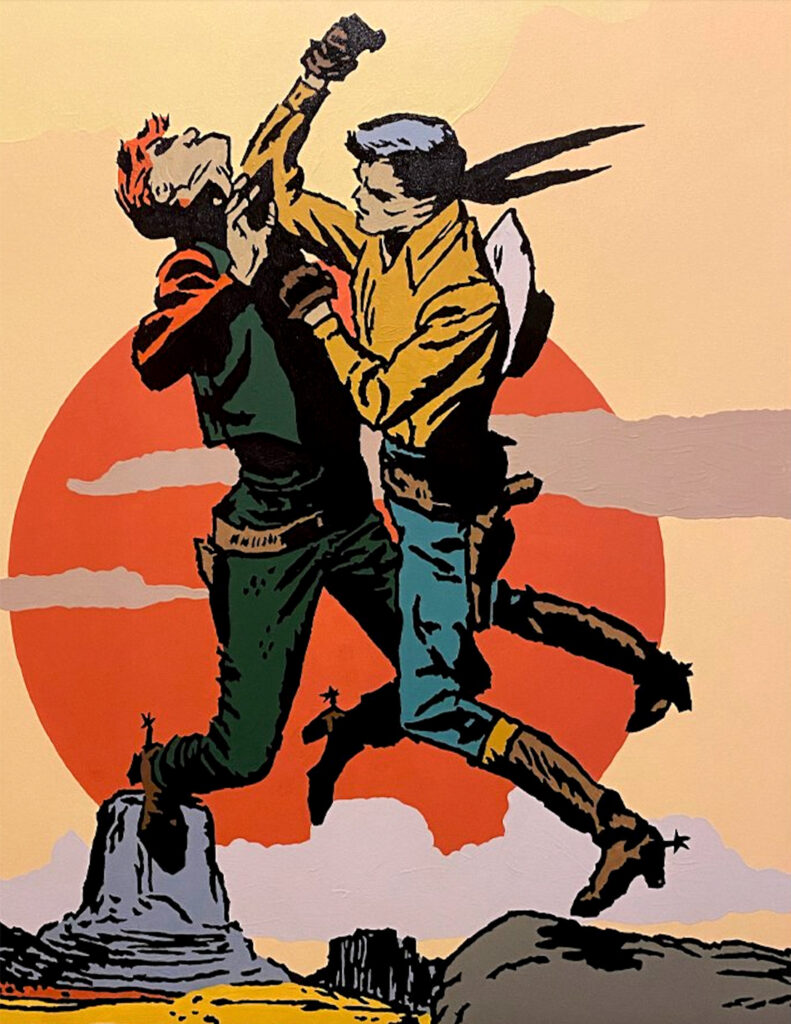

But for the past six years Walker [cyruswalkerart.com] has been tinkering with a fresh take on old subjects—namely, vibrant acrylic/oils inspired by the mythical West. Call it a 21st century reimagining of a Beadle and Adams half-dime novel or a 1950s Dell comic book. The artist himself describes his work as “a split between the reality of Western culture and the more fictional narrative quality of the Western genre. I find that paradox to be incredibly interesting to focus on and wrap your mind around.”

Comic books and films may have been Walker’s introduction to the West, but the West wasn’t what drew Walker to Montana. He was attending a liberal arts school in rural Maine but wanted something more traditional—“that experience of walking around a real campus,” he says. “I wanted more of an urban experience. I find it interesting that I moved to Bozeman, Mont., for an urban experience.” The city had a population of slightly more than 37,000 when he arrived in 2010, but Walker had never lived in a town that big. “It seemed huge,” he says. “Walking around campus, and all the big brick buildings, and all the people—I was overwhelmed. That was exactly what I was looking for.”

He took breaks from college to work so he could pay his tuition. One ultimately transformative job placed him in a Bozeman antique store, which required him to seek objects at estate sales, old ranches and the like. That turned him on to collecting old books, the illustrations in which grabbed his imagination.

“My studio,” he says, “is pretty much set up like that antique store.”

He also met his wife, Whitney, in Bozeman.

After graduation Walker first worked as a graphic designer, then turned to creating rodeo posters on the urging of Bob Coronato, a Wyoming-based Western artist known for such work. “Go for it, kid,” Bob told Cyrus. “Just make them your own.”

Walker’s first poster was for the World Famous Miles City (Montana) Bucking Horse Sale. “That was my first touch of really fine art,” he says, “sort of a bridge between fine art and design. But it also allowed me to take a really good look at the Western genre.” He was particularly struck at how tourists from back East would buy brand-new boots and cowboy hats just to wear to a rodeo.

“When someone says, ‘Western movie,’ or, ‘Western theme,’ your brain automatically goes to the more Hollywood aspect of the genre,” Walker says. “But that’s not entirely true of the culture itself. My brother-in-law has a ranch outside of Miles City, and I see how they live, and it’s nothing even close to what you see in the movies. They’re just normal folks.”

Regardless, that “idea of the West” began to percolate, and Walker started painting his signature mythical images, trying to capture “that break point, right before or right after something happened—something that you’d see in a movie or in real life. Right before the rider falls off. Right before the calf gets his nuts nipped. That kind of scene.”

The Walkers moved to Helena in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic, “when studio space was impossible to find, and everyone was working at home.” Knowing how messy he could be while painting, Cyrus “unfinished” their basement. “I took all the carpet out, removed everything that I could.”

Walker typically works on a weekly schedule. On Mondays he’ll work on sketches and cut lumber to stretch canvas. Tuesdays he’ll start painting, taking breaks from the easel to build more canvases and start more sketches. He’s usually able to finish one 56-by-35-inch painting (his go-to size) a week, “sometimes more, if I feel like losing sleep.”

When not painting or prepping, Walker is often out hiking, camping and photographing landscapes for research. He also remains a hunter-gatherer of the genre. “I’m always collecting old books and comic books and stashing them away,” he admits.

Western art and history still fascinate him.

“Partly why I found it so interesting to focus on it is that it’s location-based and vision-based,” he says. “There’s no time period for Western art—not like the Baroque, Renaissance, Victorian periods—even though it dates back to the 1800s or even earlier when European artists were coming over to the United States.”

Walker is also fascinated by the public works art projects of the Works Progress Administration, which between 1935 and ’43 hired hundreds of artists to create thousands of paintings, murals and sculptures in such municipal buildings as post offices, courthouses, schools, hospitals and train depots. “They were meant to inspire and bolster and empower the people of the United States, who were going through some really rough times,” Walker says. “That was probably where the genre officially split from reality because…the government paid artists to make up scenes especially compelling and fictional in narrative.” Instead of painting what they had lived or witnessed, as Charles M. Russell did during his early years, these artists, notes Walker, were “remembering something or were taken by some fantastic scene they had in their minds.”

His deep dive into Western mythology keeps Walker busy. “I think I’ve finally gotten to the point in my life where painting is all I truly want to be doing and what I get the most satisfaction by doing,” he says, “drawing attention to that strange sort of phenomena that happens when people think of Western things.”