A Disease in the Public Mind: A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War

Thomas Fleming, Da Capo Press

Thomas Fleming has carved out a niche for himself as a serious revisionist—that is, he always is willing to consider an alternative view to a popularly held belief and turn it on its head. A Disease in the Public Mind—the phrase derives from James Buchanan’s belief that such an affliction resulted in John Brown’s Raid and the Civil War—is likely to be the most controversial of his nearly 20 nonfiction works.

With a contrarian’s eye for facts others tend to overlook or minimize, Fleming is always probing and incisive. But he can also be too taken by his own arguments to see any flaws. In his new book, for instance, Fleming notes that planters in the antebellum South commonly appointed blacks to positions of authority such as overseer. “Managing plantations,” he writes, “was by no means the only goal to which a black man might aspire in the Deep South, even though he was a slave….There were many skilled black artisans, blacksmiths, carpenters and coopers. They operated as virtually free men.” While that’s true, it should be pointed out that such men were relatively free compared only to other slaves.

Fleming perhaps overstates the point when he writes that “Black men and women have been given very little credit for the South’s remarkable wealth. It is time to revise that mindset. The slaves participated in the system, not as mere automatons but as achievers….” Black historians have pointed this out for some time, but have also emphasized that by far the largest part of the South’s wealth was the slaves themselves, and they were considered property.

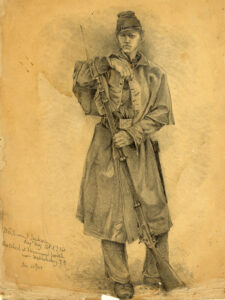

In some cases Fleming unearths old arguments that should be left buried: “It seems inevitable that, sooner rather than later, Southern masters would have had to confront… slavery’s greatest failure: its lack of freedom.” I’m inclined to think that it would have been later: much, much later. Had the Southern ruling class been so inclined in the early 1860s, it might have been able to outfit thousands of slaves in Confederate gray. Instead blacks fled to the North and joined the Union Army.

Regardless of these criticisms, Fleming’s book deserves to be read and debated—as an antidote for lazy thinking and too easily held assumptions about what preceded our country’s costliest war.

Originally published in the August 2013 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.