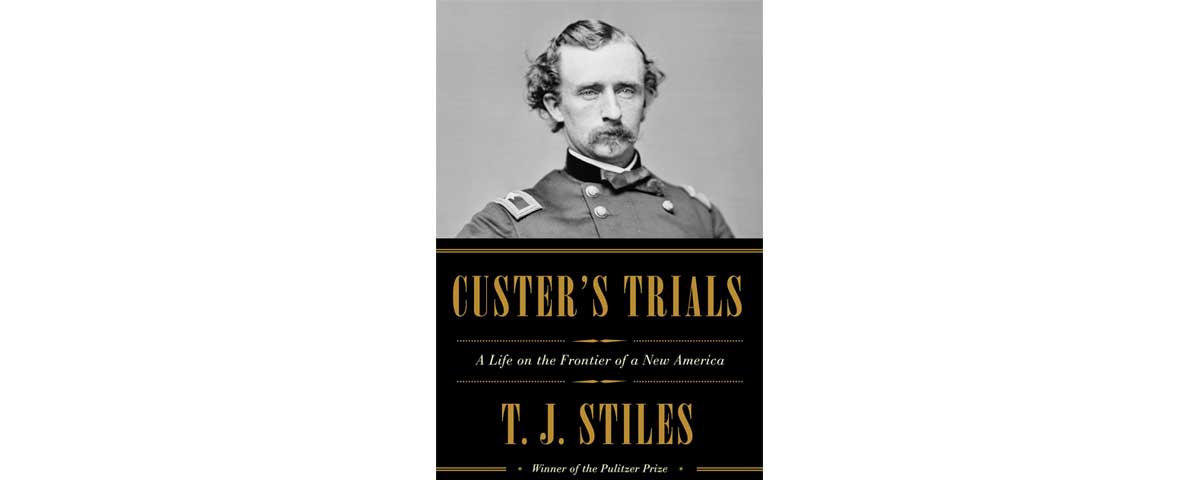

Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America

By T. J. Stiles.

Knopf, 2015. $30.

Reviewed by Alison Owings

IN MOST OF INDIAN COUNTRY, the reputation of George Armstrong Custer is unanimous: he was a murderous fool. But in what Native Americans call the “dominant society,” his reputation has varied ever since that deadly debacle in Montana, the 1876 battle of the Little Big Horn. The task that Pulitzer Prize–winning author T. J. Stiles set for himself is to examine Custer’s personal and professional life before that debacle and within the context of a changing United States.

An early note presages what is to come: Custer, in essence, was “the antiorganization man, unable to thrive in an institution or corporate environment.” At West Point he was a “self-absorbed miscreant” who graduated last in his class. Instead of studying, he effected a role as jokester and philanderer. (His resultant gonorrhea may have been why he and his wife, Libbie, had no children.) He also grew adept at “cultivating Southerners,” starting with fellow cadets. Later, writes Stiles, he “embraced Southern extremism.”

Nonetheless, he remained loyal to the Union during the war, becoming the North’s flamboyantly garbed “Boy General of the Golden Locks.” He was only in his early 20s when he first inspired his troops, then newspaper reporters and the public, riding with seeming fearlessness into battle after battle, including Gettysburg, shouting rallying cries and brandishing his saber. As Stiles reports in detail, Custer also showed cunning and logistical dexterity in attacking rebel troops.

Yet he repeatedly fraternized with the enemy. In 1863 he crossed the Rappahannock “under a flag of truce to pay a social call on Brigadier General Thomas Rosser, his friend from West Point, now a Confederate cavalry officer.” Custer later reported having had “a fine time over there.”

Readers learn, too, that after Custer’s glory days in the Civil War and his reveled-in celebrity, the couple’s postwar focus was to extend Custer’s glory, but that proved elusive. In later military assignments, one leading to a court-martial for desertion, Custer showed himself to be a poor manager and leader, who could be remarkably cruel to some of his soldiers. His final command, to lead the 7th Cavalry against the Lakota and Cheyenne, was expected to set his reputation right.

Stiles handles the famous “Last Stand” at Little Big Horn as an epilogue, instead going to great lengths to examine Custer’s many faults and show how his behaviors and skills clashed with a rapidly evolving America. MHQ

ALISON OWINGS is the author of Indian Voices: Listening to Native Americans.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2016 issue (Vol. 28, No. 4) of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Reviews: Unsung Conflicts.

Want to have the exquisitely illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!