‘Oh, the infamous wretches! It makes my blood run cold to witness the devastation that surrounds us!’

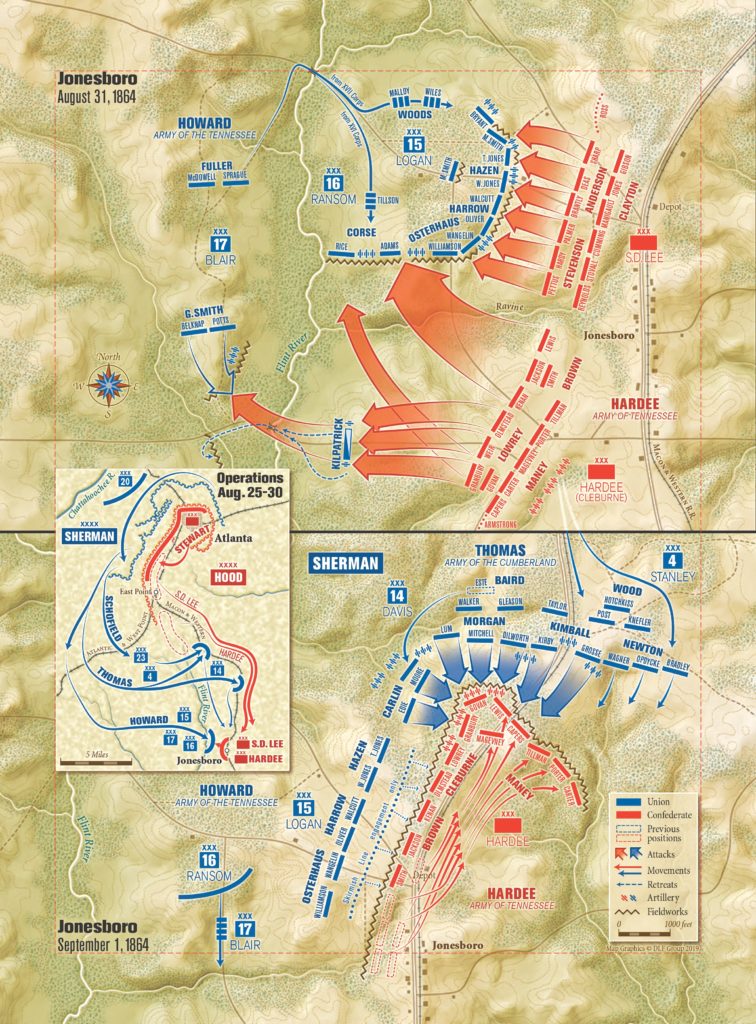

Union commander Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s decision in late August 1864 to abandon the Siege of Atlanta ultimately resulted in the fight at Jonesboro. While leaving a single corps to guard a bridgehead over the Chattahoochee River, Sherman ordered the bulk of his army—six corps, numbering roughly 60,000 men—to march west and south of Atlanta and cut the last rail lines into the city. On August 28, 1864, Union troops reached the Atlanta & West Point Railroad at two points, tearing up a stretch of the line the following day. Confederate Army of Tennessee commander Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, having sent the majority of his cavalry on a raid under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, was unsure at this point of Sherman’s ultimate intentions.

The Macon & Western, the final railroad leading into Atlanta, became the next Union target, the Federals hoping to reach the line and wreck it by August 31. By the evening of August 30, Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s troops had crossed the Flint River and begun entrenching on a ridgeline only a half-mile east of the Macon & Western. When Hood learned that a Federal force had crossed the Flint, though he wasn’t sure what unit, he ordered Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee to move south with two corps and drive Howard back across the river.

Captain Phillip K. Smith’s regiment, the 24th & 25th Texas Cavalry (Dismounted), was part of Brig. Gen. Hiram B. Granbury’s Brigade, in Hardee’s Corps. After marching overnight, Granbury’s men reached the vicinity of Jonesboro on the morning of the 31st. Troops from Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee ‘s Corps, also part of Hardee’s command, arrived later, and it was roughly 3 p.m. before Hardee had his force ready for an advance. Hardee planned to attack en echelon from the left, with Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s Division (under Brig. Gen. Mark P. Lowrey at Jonesboro, as Cleburne was commanding Hardee’s Corps) opening the assault and turning the Federal right flank. Once Cleburne’s brigades and the other two divisions of Hardee’s Corps had driven back the Federal line, Hardee would have Lee’s Corps advance.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, Lee attacked too soon, suffering a bloody repulse from the entrenched Federals. Granbury’s Brigade was on the extreme left of the entire line, with Captain Smith’s 24th and 25th Texas serving as the battalion of direction. Granbury’s advance encountered dismounted Union cavalrymen behind rail barricades a few hundred yards east of the Flint River supported by artillery batteries across the stream. Captain Samuel T. Foster, another company-grade officer in the 24th and 25th Texas, wrote that the breechloaders and six shooters of the Union horsemen “fairly made it rain bullets as long as they had any in their guns, but as soon as they gave out, and we getting closer to them every moment, they couldn’t stand it but broke and ran like good fellows.”

Granbury’s orders were to drive opposing forces across the Flint but did not let his own command follow to the western side the stream. When one of Granbury’s regimental commanders decided his men could not occupy a line on the river without driving off a Federal battery on the other side, some Texans, along with other troops from Cleburne’s Division, crossed the Flint. Granbury ordered an immediate withdrawal across the river and fell back to the Jonesboro and Fayetteville Road.

The uncoordinated Confederate attacks on August 31 were a failure. North of Jonesboro, the Union 23rd Corps reached the Macon & Western that day and destroyed sections of the railroad. On the night of the 31st, Hood ordered Lee to march his corps back to Atlanta, concerned that the Federals to the south might turn and march toward the city. This left the Confederate army in a precarious situation. Hardee’s Corps was now isolated from the rest of Hood’s troops, facing a far larger force of six Union corps.

Granbury’s Texans awoke at 3 a.m. September 1, and by daylight occupied a position a mile north of Jonesboro. On the right, Brig. Gen. Daniel C. Govan’s Arkansas Brigade eventually manned a line of hastily built defenses that formed a sharp salient bending eastward to protect the Macon & Western. Around 1 p.m., massed Union troops overwhelmed Govan’s men and other Confederate brigades to their right. The capture of hundreds of Govan’s Arkansans and the retreat of the balance of his brigade resulted in the Federals pouring enfilading fire into Granbury’s adjacent Texans. Granbury responded by ordering his troops to change front to the rear on the left battalion. Captain Foster wrote that after executing this movement at the double quick, the Texans waited until the Federals had sent off the captured Arkansas troops before opening fire.

Soon, Southern reinforcements began arriving to contain the Federal breakthrough. Tennesseans under Colonel George W. Gordon reported to Cleburne and received orders to retake Govan’s trenches. Gordon’s Brigade assisted Granbury in keeping the Federals at bay until the firing died down. About 11 p.m., Hardee’s Confederates withdrew south along the Macon & Western toward Lovejoy’s Station. Captain Foster of the 24th and 25th Texas claimed that during the retreat the Rebels could hear explosions to the north in Atlanta as Hood abandoned the city and destroyed ordnance that could not be removed. While Smith wrote that his brigade lost 175 men in the two-day clash at Jonesboro, Granbury’s official report puts the losses in his command at 34 dead and 154 wounded, for a total of 188.

When Sherman learned on September 3 of the capture of Atlanta by his 20th Corps, he wired Washington that “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.” The fall of Atlanta proved critical, along with other subsequent Union victories in the Shenandoah Valley, to secure Abraham Lincoln’s victory at the polls in November 1864.

The following letter by Captain Smith describes his unit’s participation at the Battle of Jonesboro. Smith’s letter appeared in the November 7, 1864, issue of the Houston (Texas) Tri-Weekly Telegraph.

Smith remained with the 24th and 25th Texas until late January 1865 when he received an 85-day leave of absence. The Liberty, Texas, native likely didn’t return to his regiment before the war’s end, instead receiving a parole in Houston on June 24, 1865.

Letter from Georgia

Camp 25th Texas

near Jonesboro, Ga.

Sept. 9, 1864

Dear Wife:

Since my last of August 28th, we have had rough times, and a great deal of hard fighting, in which we have met with loss and defeat, the result of all of which is the evacuation of Atlanta, and the falling back of our army twenty miles. Fortunately our little company, although participating in all the fighting, have suffered little compared with others. We have but four casualties as follows: Sergeant Jas McMurtry, wounded in right hand (two fingers amputated), Oscar DeBlanc, in head, Caesar DeBlanc and [A.J.] Jack Gill were bruised by a solid shot passing through a rail pile, behind which they were posted, throwing rails upon them; and while being conveyed to the hospital, the train upon which they were, ran into another, causing the death of 27 wounded men and again bruising DeBlanc and Gill. Many of the boys escaped very narrowly.

The boys present, although very much fatigued and broken down by hard marching and loss of sleep are all in good health and spirits.

The boys present, although very much fatigued and broken down by hard marching and loss of sleep are all in good health and spirits.

The enemy are reported falling back within the city limits. What will be their next move is hard to conjecture, some think they will try another flank movement, and endeavor to push their recent successes; while others are of the opinion that Hood will advance, besiege the city and try and cut their communications. I rather think, however, that Hood will fortify here and recruit up the army, while Sherman will make secure his position in the city, attend to the raiders that are now annoying his rear, and accumulate supplies at Atlanta for further aggressive operations at some future period.

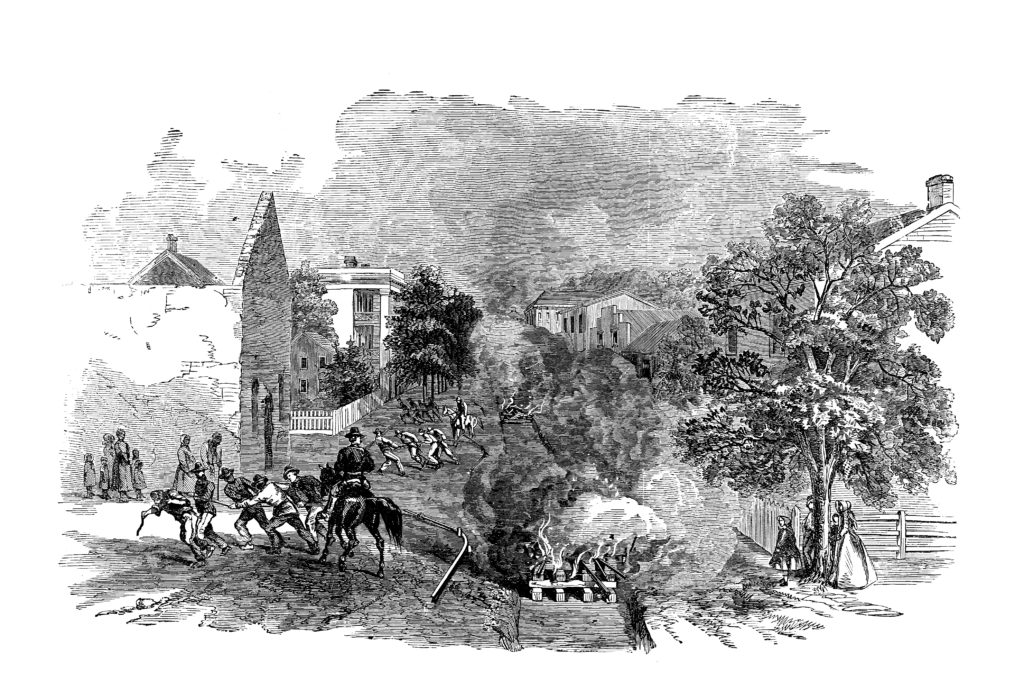

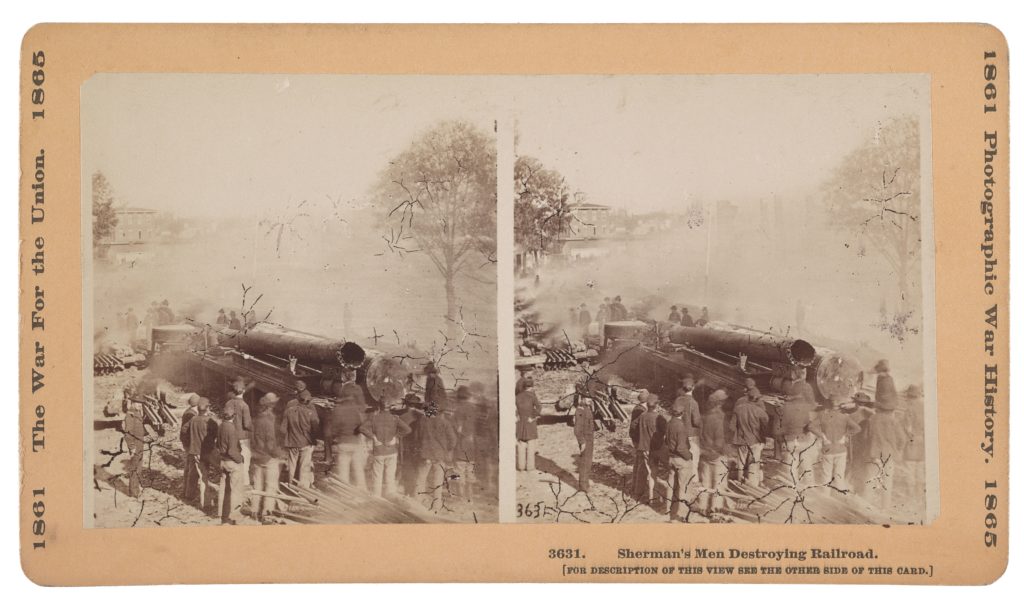

The enemy have destroyed everything in their reach. Jonesboro, which they occupied several days, they turned upside down, destroyed everything and burned nearly the entire town. The same they have done with private residences and other private property throughout the surrounding country. Oh! the infamous wretches, it makes my blood run cold to witness the devastation that surrounds us.

Our losses in this brigade is one hundred and seventy five killed and wounded; none being captured. The 6th and 15th regiments of our brigade suffered the heaviest loss, about fifty. The loss of our regiment (25th) was seven killed and eighteen wounded, extraordinarily light for the amount of firing to which we were exposed. We were under fire of artillery and musketry, a greater part of five days and nights, which, a portion of the time was very heavy. [Brig. Gen. Daniel C.] Govan’s Arkansas brigade of [Maj. Gen. Patrick R.] Cleburne’s Division, lost about 600 killed, wounded and captured. General Govan is among the captured. The enemy masked their forces in front of this brigade, charged over their works, broke their lines and routed them after one of the most desperate hand to hand fights of the war, in which the enemy’s loss was very heavy. They fought five times their number and were finally overpowered. The survivors being much distressed at the thought of defeat, are burning for revenge, and have the sympathy of the entire army. Other brigades of this division lost heavily. [Major General Benjamin F.] Cheatham’s and [Maj. Gen. William B.] Bate’s divisions also lost severely. Our entire loss will probably foot up 3000, while the enemy’s will not fall short of double that number.

Nearly the whole of Hardee’s corps were engaged against three corps of the enemy, but notwithstanding the great difference in numbers, we would have in all probability, have turned this wing of the enemy, and driven it back in confusion to the Chattahoochie, if the attack had been made on the 30th instead of the 31st. The enemy had taken position, and fortified so strongly that it was impossible to move them. The attack was made at 3 o’clock P.M. The left, where our brigade had the good fortune to be, easily drove the enemy’s right, which was not so well fortified and defended (only by dismounted cavalry) from two lines of works, capturing six pieces of artillery, two of which were brought off the field, a few prisoners, many horses, small arms, &c. Our right and centre was not so fortune, as after several determined charges, in each of which they were repulsed, the entire line was compelled to fall back.

The disasters of September 1st were to a certain degree on account of mismanagement upon the part of Gen. [Mark P. Lowery], then temporarily commanding our [Cleburne’s] Division. During the night we fell back to the railroad and fortified. The next morning the enemy advanced their lines and prepared to attack us, and at a critical moment a wrong move was made, and the enemy seeing this, massed their forces behind that portion of the line just evacuated and in front of Govan’s, Granbury’s and [Brig. Gen. Joseph Horace] Lewis’ brigades, and before new works which they undertook to build were completed, charged with six lines of battle and ran right over Govan’s brigade, gaining possession of their works and throwing a considerable force on the flanks and rear of the other two brigades above mentioned, but by superhuman efforts they succeeded in cutting their way out. Granbury, seeing that his right flank was exposed by the occupation of Govan’s works by the enemy, he undertook to change his front by forming his line perpendicular with the line of his works, to prevent further advance of the enemy in his rear. It is no easy matter to move troops in good order under fire, and particularly hazardous when the fires comes from the front, flank and rear. The order was given the 6th and 15th on his extreme right to fall back, and, as the enemy had turned our own guns upon them, they were exposed to an enfilading fire of artillery and musketry, and were soon retreating in confusion.

Others, supposing it a general retreat, also turned. Gen. Granbury, finding it impossible to reestablish his new line under such circumstances, rode rapidly to the head of the column and ordered a “halt,” which was instantly obeyed. Never, perhaps, was the coolness, courage and discipline of troops more signally displayed than in this instance. The order was given for them to return to their original positions, when every man, without a moment’s hesitation, started back in a run and with a yell; and with the help of [Brig. Gen. Alfred J.] Vaugh[a]n’s brigade of Cheatham’s division, led by Gens. Hardee and Cheatham in person, charged the works, but were repulsed, and the enemy held two hundred yards of our lines, at the point where they turned, forming a semi circle. The dark curtains of night closed over this scene of singular confusion.

But the firing did not cease for some time after dark. The enemy still using our artillery upon the flank and rear, while the rattle of musketry continued for over two hours. The firing during the entire evening was as heavy as I ever heard. There were not less than 30 pieces of artillery engaged, of which we lost eight pieces, belonging to Sweat’s [Captain Charles Swett’s] and Reyno’s [Captain Thomas Key’s] batteries. At 10 o’clock the firing, except an occasional stray shot, had ceased. Our position became critical and exciting, the enemy having extended a line along the entire rear of our brigade, and so near, that we were able to hear them whisper. The enemy, no doubt, expected to capture our brigade, but as soon as all the other troops were withdrawn, and a new line established, we were ordered by an officer, or rather signalized (for he hardly dared to speak,) at 12 o’clock, to move out of our trenches in single file by the left flank, keeping well down in the ditches, and without noise, but it seemed to me that more noise was made, than upon any other occasion, and the enemy must have been familiar with our movements, but they were afraid to make an attack. We were soon out of danger, a strong line formed, pickets thrown out, and by day light everything had been removed from the town (Atlanta,) and the troops upon the move in the direction of Lovejoy Station, six miles below on the Macon railroad.

The train conveying the wounded left the town just as the enemy drove in our pickets, and appeared in full sight on a hill, half mile distant, coming at a double quick. Shell was bursting around the train and Minnie balls flying thick and fast; and the confusion caused was distressing, as the wounded were handled very roughly, but being so overjoyed at the idea of escaping capture by the enemy, the pain of their wounds were entirely forgotten, notwithstanding the excessive agony the rough handling must necessarily have produced. Seven wounded were unfortunately left, and fell into the hands of the enemy. Act’g [Assistant] Adg’t Gen’l. [Sebron G.] Sneed, of Granbury’s staff had his leg and thigh badly crushed, by an accident on the road by collision, which caused the deaths of 27 and wounding of 100 of those already wounded and mangled soldiers.

At Lovejoy Station our lines were formed and we began to fortify, and at 12 o’clock the enemy appeared in our front driving in our skirmishers, and fortifying their lines near ours, and a constant fire day and night kept up until the morning of the 6th, when they withdrew, abandoning their works, tearing up the railroad as they retired, doing every other conceivable damage to public and private property.

Nothing but the capture of Atlanta saved Sherman’s army from hopeless demoralization and ruin. In case [Maj. Gen. Nathan B.] Forrest can operate in their rear, they may yet be flanked out of Atlanta.

Gen. Wheeler with about [illegible] thousand cavalry has for some weeks been in the enemy’s rear, but has not accomplished much, except tearing up railroads, which is repaired with great dispatch and scarcely felt by the enemy. After the fight the enemy buried our dead, but so badly that it had to be done over. In many places their feet and hands protruded from the ground. The stench from the battlefield is horrible at this distance—one and a half miles. All of our wounded are doing well and fast returning to duty.

Had I time and room I might interest you with personal gallantry of our little company, but at present * * *

Your devoted husband, P.R[K]. Smith

Keith Bohannon is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia and an author, most recently, of an essay about General John B. Gordon in Stephen Cushman and Gary Gallagher, eds., Civil War Writing: New Perspectives on Iconic Texts (Louisiana State University Press, 2019). This story appeared in the February 2020 issue of Civil War Times.