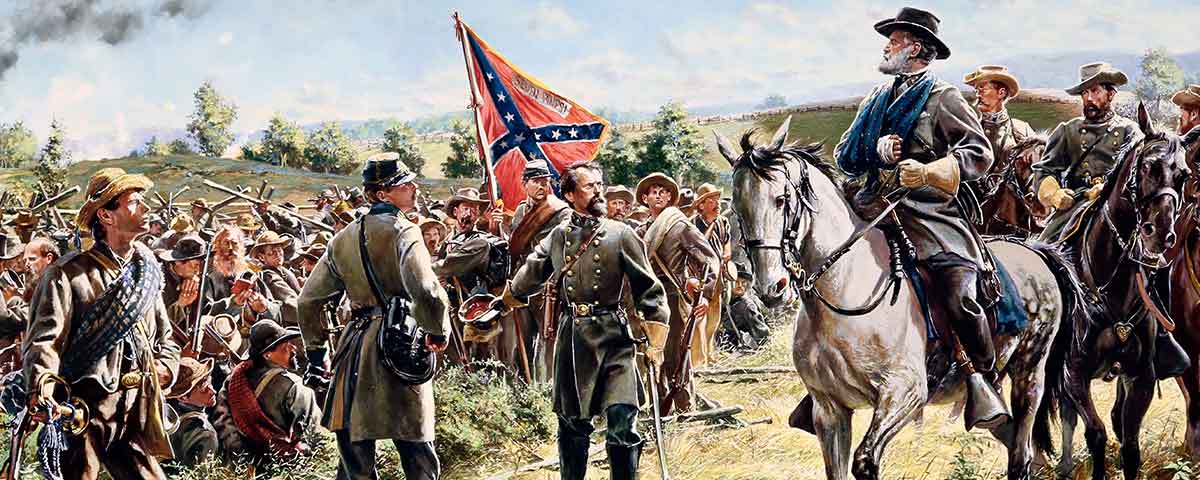

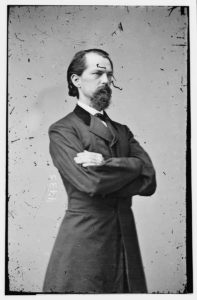

Already a Confederate hero, John B. Gordon still couldn’t resist tweaking the record a little

“My rifles flamed and roared in the Federals’ faces like a blinding blaze of lightning accompanied by the quick and deadly thunderbolt. The effect was appalling. The entire front line, with few exceptions, went down in the consuming blast. The gallant commander and his horse fell in a heap near where I stood—the horse dead, the rider unhurt. Before his rear lines could recover from the…shock, my exultant men were on their feet, devouring them with successive volleys. Even then these stubborn blue lines retreated in fairly good order. My front had been cleared; Lee’s centre had been saved; and yet not a drop of blood had been lost by my men.”

That’s how John Brown Gordon, colonel of the 6th Alabama Infantry, described in his widely read Reminiscences of the Civil War the initial Union advance against the Sunken Road (a.k.a. “Bloody Lane”) at Antietam. The account by Gordon, who was wounded five times in the Sunken Road, is wonderfully descriptive and quotable, and has largely been accepted without pause as an accurate description of the dreadful fighting that day. A modern reviewer of Gordon’s book effused that his “first hand description of the battle…causes the reader to hear the cannons and smell the smoke.” No one can question Gordon’s skill with a pen or his courage and ability to manage troops in battle.

Considerable attention has been paid to Gordon’s description of his interaction with wounded Union Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, and how he shaped the story to make himself the central figure and claim credit for things others had done. The Gordon–Barlow incident is part-truth and part-myth. Gordon’s “Sunken Road” account has eluded the same level of scrutiny. How does it stand up to the evidence of the battle now available?

On page 84 of Reminiscences, he describes the initial approach of the Union attackers:

The men in blue filed down the opposite slope, crossed the little stream [Antietam], and formed in my front, an assaulting column four lines deep. The front line came to a “charge bayonets,” the other lines to a “right shoulder shift.” The brave Union commander, superbly mounted, placed himself in front, while his band in rear cheered them with martial music. It was a thrilling spectacle.

It is possible today to stand about the exact spot where Gordon awaited the Union attack. Several things are evident immediately. There is no way he could have seen the Federal soldiers, of William French’s 3rd Division, 2nd Corps, filing down the east bank and crossing Antietam Creek. To read they “formed in my front,” one imagines they were close and in full view of Gordon’s position. But French’s men formed for their advance in the East Woods, more than a mile north of this position, and unless Gordon climbed up the hill in the right front of his regiment, he couldn’t have seen them. At that distance he also could not have observed the front rank come to “charge bayonets.” For one, no soldier in French’s leading brigade mentions coming to “charge bayonets.” No band was playing, and it could not have been heard anyway over the roar of artillery fire. There also were numerous mounted Union officers, not just one. Finally, we need to ask how it was possible for Gordon to know at over a mile the enemy were new recruits or “fresh troops from Washington.” It is likely he learned these acts after the war.

Those unfamiliar with the battle’s details might imagine the only thing standing between the utter defeat of Lee’s army and its survival was Gordon and his regiment. “Every act and movement of the Union commander in my front clearly indicated his purpose to discard bullets and depend upon bayonets,” he wrote; “…It was my business to prevent this; and how to do it with my single line was the tremendous problem which had to be solved and solved quickly; for the column was coming.” Neither Robert Rodes, Gordon’s brigade commander, nor any other unit are ever mentioned. It was Rodes’ business, not Gordon’s, to assure the Federals did not break through his line. The only way we know any other Confederates were involved in the defense is when Gordon mentions talking to “the chivalric Colonel Tew, of North Carolina” as Tew is shot in the brain by the first Union volley. This was Charles C. Tew, colonel of the 2nd North Carolina, of Brig. Gen. George B. Anderson’s Brigade, which fought beside Rodes’ men in the Sunken Road.

Tew, however, was mortally wounded well into the combat, after being notified he was now in command of the brigade, with Anderson wounded. When asked to acknowledge receipt of the message, Tew bowed and tipped his hat, but was struck in the head as he did.

Even Gordon’s own description of his fifth wound omits a key detail. He writes that a bullet struck him squarely in the face, knocking him unconscious, and that he fell forward, face in his cap, and would have been “smothered by the blood running into my cap” had not a bullet hole in it allowed the blood to drain. A litter team bore him to the rear and he did not awake until later that night. A contemporary account by a 6th Alabama soldier revealed, however, that after his fifth wound Gordon “found…the strength to crawl 100 yards to the rear,” where he was discovered covered with blood, and then assisted from the field.

It seems unlikely Gordon simply forgot all this. More likely is that a tale of him falling among his men would seem more heroic than the truth. Whenever Gordon chose to exaggerate, bend, ignore, or invent incidents, he almost always did so deliberately either to advance his political agenda—he was a post–Civil War U.S. senator (1873-80) and later governor of Georgia (1886-90)—or to elevate himself to a central role in the drama. There is value in his Antietam account, but it should always be used with care and caution.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.