An ‘earnest’ rebel from Alabama helped save Antietam and Gettysburg for future generations

The soldiers of Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s Division waited in the West Woods on September 17, 1862. Union shrapnel, shell, and solid shot rained down upon the woods, at times sending tree limbs crashing down upon the soldiers below. Captain William McKendree Robbins, acting major of the 4th Alabama, was standing beside a friend talking when a shell or shell fragment struck the young man—the “noble and handsome” Lieutenant David B. King—in the head, spattering Robbins with blood and brains and hurling a piece of King’s skull into the ranks of the 11th Mississippi. No human can witness such an event and not be traumatized, yet Robbins had no time to dwell on the horror. Minutes later, a “to arms” order was sounded and Hood’s Division poured out of the woods to launch a devastating counterattack.

The 4th proceeded double-quick up the Smoketown Road in column as the rest of the division deployed in the fields to their left. “The bullets began to zip about us, very lively,” recalled Robbins, who was disturbed that Captain Lawrence H. Scruggs, the acting lieutenant colonel and regimental commander, had not deployed the 4th Alabama. The problem soon resolved itself when a bullet struck Scruggs in the foot and command fell to Robbins. He deployed the regiment at once. As it advanced toward the East Woods, elements of the 21st Georgia of Colonel James A. Walker’s Brigade joined on its right.

Under the pressure of Hood’s counterattack, the Federal troops firing on Robbins and his regiment fell back and the Alabamians and Georgians pushed up into the East Woods. Robbins halted his advance about midway in the woods and had his men take advantage of the abundant cover. They were soon joined by the 5th Texas, which moved to the right of the line. All told, about 500 Confederates now occupied the woods.

Hood’s counterattack roared up to the northern edge of the Miller cornfield, where Union resistance inflicted devastating casualties and drove it back. But Robbins and his small force held on, repulsing all efforts to dislodge them. Because of their cover, Robbins’ losses were not heavy, but one of his casualties was personally devastating. His younger brother, Madison, serving as an enlisted man, was shot through the throat and killed.

Needing men and ammunition, Robbins sent back repeatedly for both. Colonel Evander M. Law, Robbins’ brigade commander, encouraged the captain to “hold your position, Hill is moving to your support,” meaning troops of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Division. As for ammunition, Robbins remembered, “somehow we in the wood were overlooked & no supply came,” so his men scrounged from the dead and wounded. Garland’s Brigade, of Hill’s Division, commanded by Colonel Duncan K. McRae, soon entered the woods behind Robbins. About this time, a new Union advance approached the woods from the north. After a brief resistance, McRae’s Brigade fled to the rear. Without ammunition, his numbers dwindling, and the enemy threatening to envelop his right flank, Robbins had no choice but to retreat.

It was a perilous withdrawal. The enemy fire was so heavy that Robbins concluded he could not survive. Determined not to be shot in the back, he kept his face toward the Federals while his men were “dropping all about me.” When he arrived at the edge of the woods unscathed, he recalled, “Thinks I to myself I believe I shall escape after all,” and he made “a little better time” to the West Woods. His small mixed command had held the East Woods for more than 90 minutes, yet no ranking officer on the Confederate side seemed to understand what he had done. He received no acknowledgment in either Law’s or Hood’s after-action reports. Robbins was sick after the battle—a common occurrence for those exposed to severe trauma and great stress—and did not write a report, which may account for his lack of recognition.

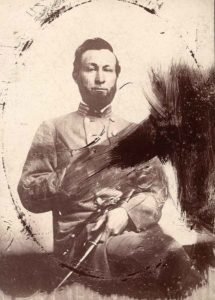

Robbins served through the rest of the war, fighting at Little Round Top at Gettysburg and suffering a severe wound in the Wilderness in May 1864. But he returned to duty and surrendered with his regiment at Appomattox. Although he served in an Alabama regiment, Robbins was a North Carolinian. He had moved to Alabama with his wife in 1855 to open a female college, but soon made a career change from education to the law. His wife died three years later, leaving Robbins a widower with two young children. He left his Selma law practice, volunteering immediately when war came.

After the war, he returned to North Carolina. He had married his wife’s sister during the conflict and they settled in Salisbury, where Robbins resumed a legal career. In 1868 and 1870, he was elected to North Carolina’s Senate, then served 1872-1876 as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Robbins was a staunch conservative who opposed Reconstruction, including African-American suffrage, and supported prohibition. While he took great pride in his service as a soldier, he did not cling to the cause of the Confederacy or lament its defeat. “There was not a more sincere or thoroughly earnest ‘rebel,’ I suppose, in the Southern armies,” he wrote in 1891, “but it’s all over and nobody is sorry for that.” He now embraced our “great common country which will soon be the center and acknowledged greatest of the powers of the world.”

In 1891, 10th Maine Infantry veteran John Gould, who was attempting to track down what regiment he had fought in the East Woods and which Rebel unit mortally wounded Maj. Gen. Joseph Mansfield, contacted Robbins. Gould’s inquiry opened memories Robbins had locked away for years. They flowed out in an 18-page letter to the New Englander. He teasingly admonished Gould “for having tempted me to ‘fight’ my battle again which I have never done before.” Through their correspondence, it became clear to Robbins that Gould’s regiment might have been the one responsible for killing his brother. Yet instead of being angry, Robbins warmly embraced Gould as a friend, signing his many letters, “With best wishes, Your friend.”

Four years later, in 1895, President Grover Cleveland selected Robbins to serve on the park commission for the newly created Gettysburg National Military Park. Thirty-two years after trying to fight his way up Little Round Top, Robbins would return to Gettysburg, this time to help develop a park for all Americans. In our next Crossroads we will take up what he did there in the final years of his life.

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.