[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he 1st Texas Infantry earned a macabre place in history at the Battle of Antietam, suffering 186 casualties out of 226 men engaged—an 82.3 percent loss rate considered the highest for a single regiment not only at Antietam, but also the entire war. New evidence suggests, however, that another Confederate regiment—the 6th Georgia—might have incurred a higher level of devastation than the 1st Texas that day. We may well never know for sure, but it is a valid possibility.

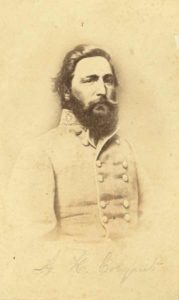

The 6th was one of four Georgia regiments, as well as the 13th Alabama, in Colonel Alfred H. Colquitt’s Brigade, part of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Division in the Army of Northern Virginia. How many men the 6th took into the battle remains in question. One member of the regiment recorded its strength at 320, but others had the total at about 300, and another estimate was as low as 200. In his studies of the battle, Antietam scholar Ezra Carman decided to go with the average: 260.

Colquitt’s Brigade—still referred to by some as Rains’ Brigade, a nod to former commander Maj. Gen. Gabriel Rains—spent a night of September 16 in Sharpsburg’s soon-to-be-immortal Sunken Lane. At about 7:30 a.m. on the 17th, Colquitt received orders from General Hill to reinforce the fighting around the Miller Cornfield and the East Woods. The brigade marched quickly in the face of sweeping Union artillery fire. It passed the burning Mumma Farm buildings and pushed north across a plowed field toward the East Woods. Wounded soldiers from the fighting ahead were returning in a fairly steady stream. Some encouraged their swiftly moving comrades to “give ’em hell boys.” One of Colquitt’s men never forgot the irony. In the coming hour, he would write, “we went in and got hell ourselves.”

When the brigade reached the Smoketown Road, it was met by Hill, who directed Colquitt to form into line and advance. Up front, the battle was raging fiercely. Colquitt hurried through the southwestern corner of the woods, then formed his brigade into line. When the formation was complete, the 6th Georgia was on the far right and at first entirely within the woods. The brigade had double-quicked nearly a mile, and the men were winded and the regiments strung out. Even though the 6th came under fire almost immediately, its commander, Lt. Col. James N. Newton, was displeased with the ragged line his regiment formed and ordered it to halt. Newton sent out guides to mark the right and left flanks, then had the regiment dress on these human markers until its line was “as cool as on dress parade.”

The 6th hurried to catch up with the rest of the brigade. Their movement brought the left of the regiment out of the woods into a meadow directly south of the Cornfield. All outside the woods were firing at the infantry of Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield’s 12th Corps, standing on a ridge north of the corn. Colquitt ordered his brigade to advance and drive the Federals off. The men responded by pushing into the Cornfield, loading and firing as they advanced. Many were struck as they moved, among them Major Philemon Tracy of the 6th, who was shot in the thigh. A lieutenant paused to bandage the wound and try to get the major to some cover but was shot in the side. Tracy bled to death. Despite what one of the 6th described as a “most terrific fire,” the left of the regiment reached the northern edge of the Cornfield. The right of the regiment remained in the woods.

It was at this moment that Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s brigade of the 12th Corps arrived opposite the Georgians’ right front and flank, its approach concealed by the East Woods. Most members of the 6th had their attention focused on the Federals in the open north of the corn, but Captain John G. Hanna, commanding a company on the far right flank, saw Tyndale’s unit approaching and dashed over to warn Colonel Newton that they were flanked. He delivered his message, but was killed as he turned to head back to his company, and Newton would be mortally wounded by a volley from Tyndale’s men.

That left the 6th with no field officers. Though the regiment held its position and fought stubbornly, it was soon confronted by the 800-man 28th Pennsylvania, part of Tyndale’s brigade, which had moved up through the woods on their right. Some of the Georgians saw them coming and unleashed into them what one Federal called “a withering fire” that somehow failed to check their advance. The Pennsylvanians responded by delivering a murderous volley of their own, mowing down members of the 6th literally in rows.

Ben Witcher was along the Cornfield fence, unaware of the calamity engulfing his regiment. A comrade advised him that it was time to get out. Seeing a line of men still lying down along the Cornfield fence around him, Witcher defiantly said no and to “let them come.” His friend shook several of the men to show Witcher they were all dead or wounded. Suddenly aware of the disaster sweeping toward him, Witcher started off with his friend and two other men. Union bullets cut down all of them except Witcher. The survivors of the 6th fled, along with the rest of Colquitt’s Brigade.

When they had a chance to assess the damage, it was staggering. All but two commissioned officers were dead or wounded, leaving the regiment in command of a lieutenant. In Company E, 13 were killed and 17 wounded. In Company K the carnage was 16 killed, 15 wounded, and 5 captured from 40 present. All told, 84 men were killed or mortally wounded, 115 were wounded and 30 captured. If the regiment had 300 in action this was a loss of 75 percent. But it is possible the loss was higher, for Corporal Robert Johnson wrote that only 40 men could be accounted for on September 18, which would mean a loss of 87 percent.

Playing the percentage game here can be problematic, for the number carried into battle was often not known with absolute certainty. And some units suffered such catastrophic losses that their casualties were imperfectly reported by surviving officers. Others did not even bother to report slightly wounded men. The first two are true for the 6th Georgia, and the third might be. The only thing we can know with certainty is what Ben Witcher wrote years later; “This battle was the most disastrous to my Regt of any in the war.”

Scott Hartwig writes from the crossroads of Gettysburg.