In July 1994, during a visit to Manassas National Battlefield Park, the late historian Brian Pohanka shared with me an unpublished account of the epic fighting that had occurred upon those fields August 28-30, 1862—at the battle known across the South as Second Manassas and in the North as Second Bull Run. The account had been written by Private Alexander Hunter of the 17th Virginia Infantry, who served in Company A (the “Alexandria Riflemen”). Hunter later became known as the author of a 1905 “novel” Johnny Reb and Billy Yank, and would also write about his experiences during the 1862 Maryland Campaign for the Southern Historical Society Papers and the Baltimore Sun.

The fascinating material Pohanka shared led me to the Virginia Historical Society (VHS), where I found a fragmented, never-published 1866 manuscript titled “Four Years in the Ranks” that Hunter had penned under the nom de plume “Chasseur” (French for “hunter”). There were considerable differences between the material in “Four Years in the Ranks” and Johnny Reb and Billy Yank. Notably, some of the strong views Hunter expressed in 1866 seem to have abated by 1905 when his book came out. The last sentence in his manuscript provides one striking example of that: “To every Yankee I tender most cordially my undying HATE—now and ever after.”

Hunter served throughout the war, first with the 17th Virginia and then with the 4th Virginia Cavalry. Captured June 30, 1862, at Frayser’s Farm (Glendale) during the Seven Days, he was exchanged in time to fight at Second Manassas. After being captured at Sharpsburg, the self-proclaimed “High Private” would be exchanged again. His stint with the 4th Virginia Cavalry began in July 1863. Captured once more, he attempted to escape twice, succeeding on the second opportunity and returning to his regiment for the remainder of the war.

After the war, Hunter discovered that the Abingdon Plantation where he had grown up and which he had inherited had been confiscated by the U.S. Tax Commissioner’s Office in 1864 for unpaid taxes. The taxes were to be paid in-person, and because Hunter was a Confederate soldier that could not be done. He won his lands back after Bennett v. Hunter was decided by the Supreme Court in 1870. (Ironically, former Union Maj. Gen. James A. Garfield was a member of Hunter’s legal team.) Today the ruins of Abingdon are located between parking garages at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

Hunter passed away in 1914 and was buried in the Confederate section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, a Confederate battle flag draped over his coffin.

The following account, taken from Alexander Hunter’s “Four Years in the Ranks,” begins on August 31, 1862—the day after the Army of Northern Virginia’s resounding victory over Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Federal army at the Second Battle of Manassas. Most of Hunter’s original spelling and punctuation are retained, but paragraph breaks have been added to help with readability.

En Evant! En Evant! It was near forenoon…before the order to march was given, and slowly we wended our way through the battlefield – Ah! What a contrast, war stood now in all its misery divested of all the glittering panoply – and proud display, the dead lay in heaps as they fell, in every conceivable attitude of death. The corpses were all divested of their outer clothing, not one had his shoes or hat left him – it was a sad sight to see them thus, and made one heartily curse the pillagers and the miserable camp followers that followed like birds of prey, the wake of our army, the true soldiers rarely condescend to strip his fallen enemies he leaves that to the regular plunderer – but if he finds that he has a purse in his pocket, or a good pair of shoes, & he is only carrying out his camp education, which teaches him to help himself with what he desires most.

It was a most disagreeable day – the rain fell with a steady ceaseless stream, that seemed as if it had made up its mind to keep pouring down until every thing was saturated, the mud was getting deep too – and we trudged along, too gloomy to talk with each other, but after a while we began to brighten up some, as the hasty retreat after the enemy became visible – knapsacks, guns, and all kinds miscellaneous articles belonging to the equipment of the soldier, were lying in the greatest profusion all along the road, and the men would pick up letters, daguerreotypes – and newspapers – and read them out aloud their natural buoyant spirits of the soldier soon showed itself in bursts of hearty laughter as some very funny extract would be read and some tender love passages criticized.

After these subjects exhausted themselves, the conversation naturally turned on the events of the late battle – and the various unfortunates who had been killed – grieved over….The seventeenth suffered severely, but there was an unusually large number of wounded. The bearing, and the bravery of the different men were freely discussed, and woe [illegible] the man who had acted timidly during the battle, ridicule and scorn were freely heaped upon him & he had to bear it as well as he could. Our regiment if I mistake not recaptured (or found them on the field) three or four of our colors, and took one Stars & Stripes from the enemy. Sam Coleman of Co. E was the man who took the flag – it was an act of distinguished courage, that in any army but ours he would have been promoted on the field with a commission, but his gallantry was only rewarded by the high promotion of fourth corporal.

All along the road evidences of the hasty retreat met our view. We passed a slaughtered beef – skinned and cleaned, but they were in such a hurry that they had not time to divide it – many of our regiment had fresh beef that night & consequence. No rations had been issued out to us, but most of the men had filled their haversacks with captured provisions. After a long march with frequent halts, we bivouacked for the night in the woods – and being so tired we went to sleep without taking the trouble to build any fires.

The next day it cleared up temporarily and we did not resume our march until late. I took this opportunity to look at the pocket book, daguerreotype and letters, which had remained in my pocket unforgotten, I opened the pocket book with a trembling hand, expecting to see a small fortune, in the way of a roll of bank notes[.] [J]udge of my disappointment when I found that the book was stuffed out with black thread & needles, very useful articles in their way no doubt, but not very valuable to a man whose clothes were in rags, and tatters.

Next I looked at the likeness and could not but be struck with the look of mingled sweetness, and beauty of the face – I gazed long at it, and then turned to the letters to find out who she was. It was so sad – so sweet – so touching, that it brought even tears to my eyes, a rough reckless soldier that I was. The first letter was written to him just after his arrival in the army. It alluded in touching terms to their long engagement, [illegible] her vows of love, and giving him pure & holy advice, there was a deep [illegible] in her letters, which showed that she was truly a Christian.

It was the last letter that affected me – Never in my life have I ever read an epistle, which for beauty of style, affecting words, and inimitable pathos, could approach that letter. I commenced by saying that she knew that he would soon be called upon to go through a bloody battle, and it had been the tenor of her prayers, prayers for her safety, that night after night would she dream of seeing him brought back to her all bloody and dying, that her health was suffering so, that she knew if anything happened to him – that her heart strings would snap asunder, then followed passionate appeals to God, to protect him her cherished Idol, and if he must be offered up as a sacrifice on the atlas of his country to take her away too. And I [illegible] the latter part of her last letter which ended thus, “And now my dearest Henry I must say farewell, God in his divine mercy grant that you may escape – Do your duty – and pray earnestly that he may shield you, and take you in his own good time. Farewell Henry – my mind is appressed with sad forebodings, an undefinable feeling of boding ill hangs over me. I try to shake it off but I cannot, Heaven protect my soldier boy – if he takes you Henry I will soon follow, let your prayers assend humbly to the throne of the Most High – and pray yourself for safety. One last lingering farewell – remember not to expose yourself for on your lip hangs mine. Farewell my darling. If we do not meet on this earth, we will meet in Heaven.

Fondly but sadly your ___ Lucy”

The letter was dated G.F. New Jersey – I thought, and how will you take the news, even now you are watching, and praying for him – and he lies dark and stiff – with that face that you loved so well shattered by the ball, and I thought how will she receive the news, and I thought then there is wailing and weeping up in the Northern households as well as the Southern, and many a woman in both sections of the country, were weeping over their loved ones who fell in the Second Battle of Manassas & that night the image of that girl was much up in my dreams.

The next morning we continued are march down the turnpike, the rain recommenced, and everything look[ed] blue & melancholy, a good many men now began to straggle out – and go to [illegible] houses. On we went through the mud – and the mud so thick that it was late in the evening when we arrived at Chantilly, too late to participate in the battle, the rain still poured down, and all our ammunition was wet through, our musket barrels full of water, and now uncomfortable set of men, could not be found, the only consolation we had was that the Yankees were in a worse plight than we were. It was sad to witness the destructions of waste of the once lovely Chantilly [Plantation] – a more beautiful place could not be found – but what a change was wrought on it in a few short days by the hand of the foe, the fences were all leveled – the outbuilding nearly turned down, one of the finest shade trees cut down – choice fruit trees hack[ed] down in mere wantoness, and the house itself was not spared. The furniture that was left was smashed, the plastering from the walls knocked off. Everything defiled, and defaced – it was the same old picture, and Chantilly, once the seat of elegant hospitality, and the home of wealth and refinement, was in a few hours changed into a place that was hardly decent for a hog pen.

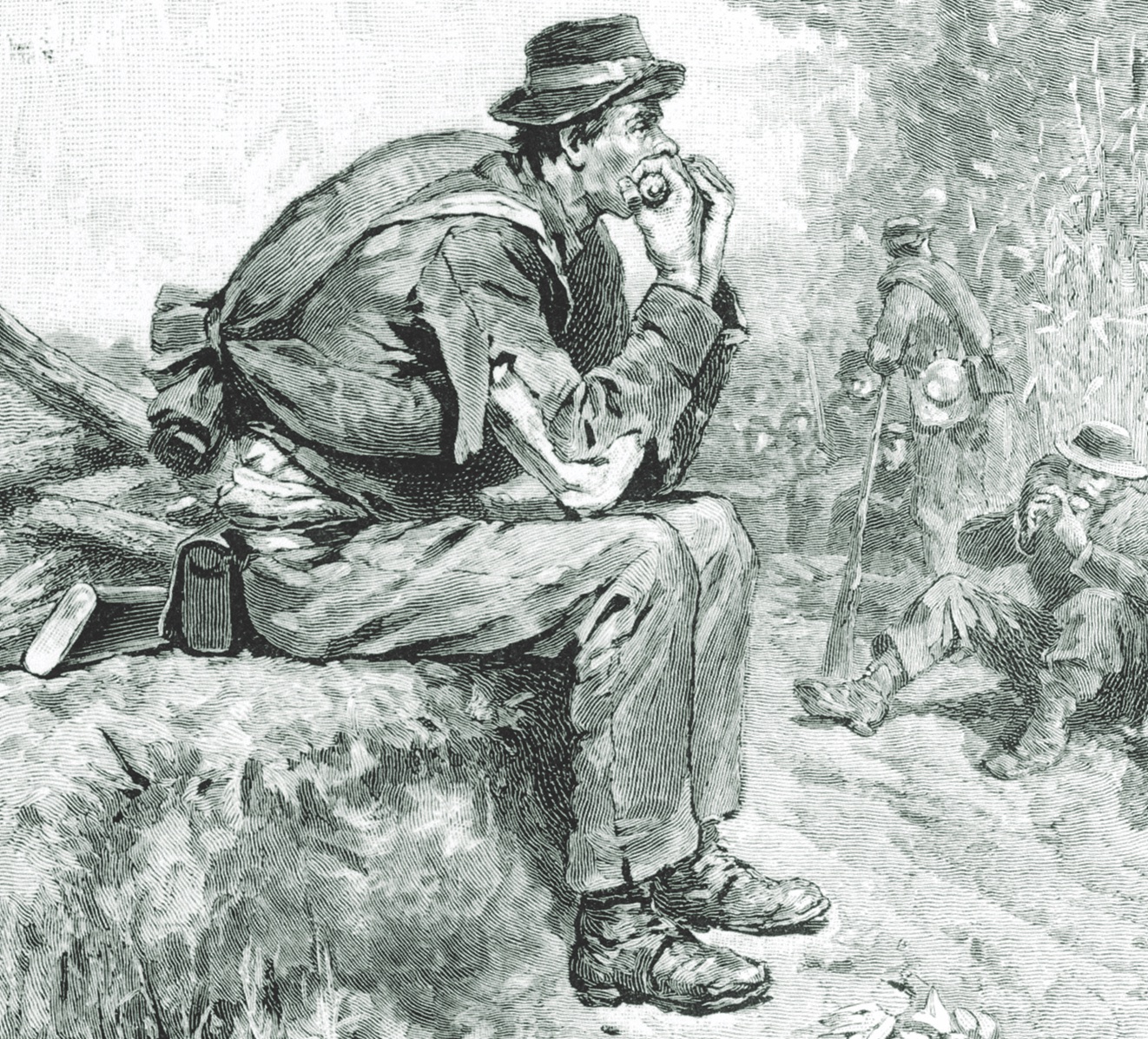

That night we had to sleep out in the rain with no covering from the inclement weather, and nothing for our beds, but the muddy earth. But such was our fatigue, after tramping all day in the mire & mud that exhausted nature accommodating herself to any circumstances gave completely out – and we rested at will as if we lay on beds of down.

In the morning [September 2] we could hardly move our stiffened limbs, and our bodies were chilled through [but] fortunately the sun came out – and its hot beams soon dried our clothes[;] still we were in a wretched situation, no rations had been issued out and those that had their haversacks [stocked] were not disposed to divide except to their intimate friends. Through the charity of one of my messmates I got a meagre breakfast, and thought as I was eating it – where’s the next coming from – that thought passed through the heads of many hungry men that morning, I have no doubt.

The next morning [September 3] we started on our march leaving behind some of our best soldiers, who wore out, and being taken sick were unable to proceed any further. Among them was my old comrade and messmate Walter A. [Addison] – by whose side I had marched and fought for two long years, he was attacked by one of those lingering camp fevers which bought so many of our soldiers the grave, he had heroically kept up – but could now march no further. It was with a heavy heart that I shook hands and bade him farewell and left him lying on the side of the road – where he found his way to some farm house and ultimately recovered.

As we marched down the pike, the citizens by every means in their power, testified their delight in being relieved from the presence of the foe, who used them so badly – the little they had saved they cheerfully divided with our hungry and foot sore soldiers, they were too kind – and their generosity bore its bitter fruits, Much better for our cause had it been, if we had marched through a section of a country bitterly hostile to us – The soldiers stopping at these houses, and being treated so kindly, felt a disinclination to rejoin their regiment with its hard marching, and untold future hardships in store for them, they could easily quiet their conscience by imagining that they felt sick, and the consequence was that every farm house for miles around had one or more soldiers as its inmates, who by doing little services for the families amply compensated them for their [illegible]. It was a terrible blunder somewhere – and moving into the enemies land – with the intention of attacking him – our army instead of being reinforced and under strict discipline, was dwindling in point of numbers and morale.

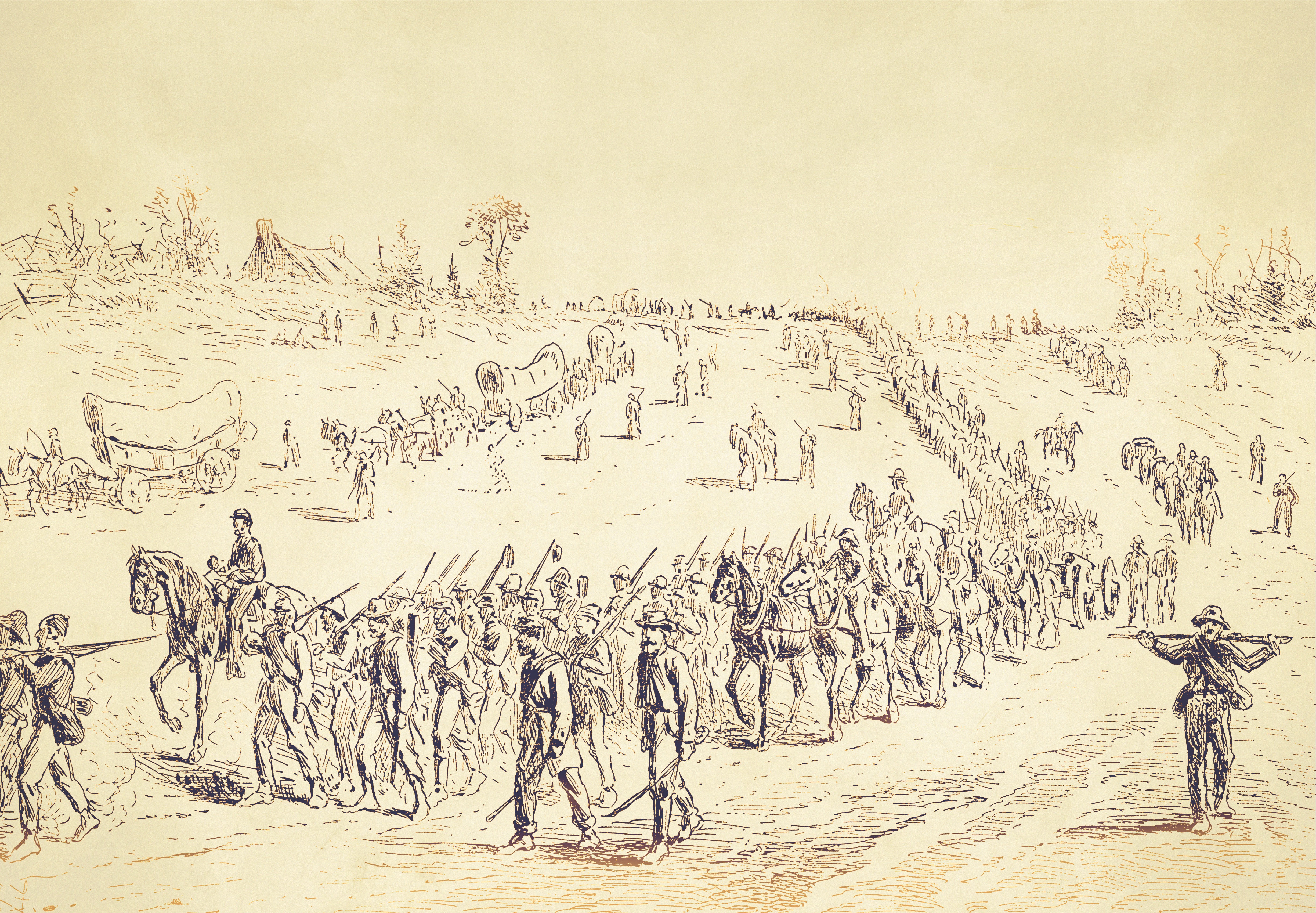

Two or three days by steady and continuous marches we reached Leesburg, we passed through little [illegible] town in the evening – the whole town stood out in the streets – to see us go by. Some waving their handkerchiefs some taken on animated [illegible] to friends – and many crying…as they bade farewell to some relation whom they thought they may never see again. We did not stop but pressed right on mile after mile we marched – and it was late at night before we halted, and then with about half the men we started with, every hundred yards, some soldier would drop out [of the] ranks, and unchecked by the officers would wander where their inclination led them, indeed during the who[le] march into Maryland, to such an extent was the vice of strag[g]ling carried to that it resembled the retreat of a demoralized army, more than it did of a body of troops flushed with success, and advancing to conquest.

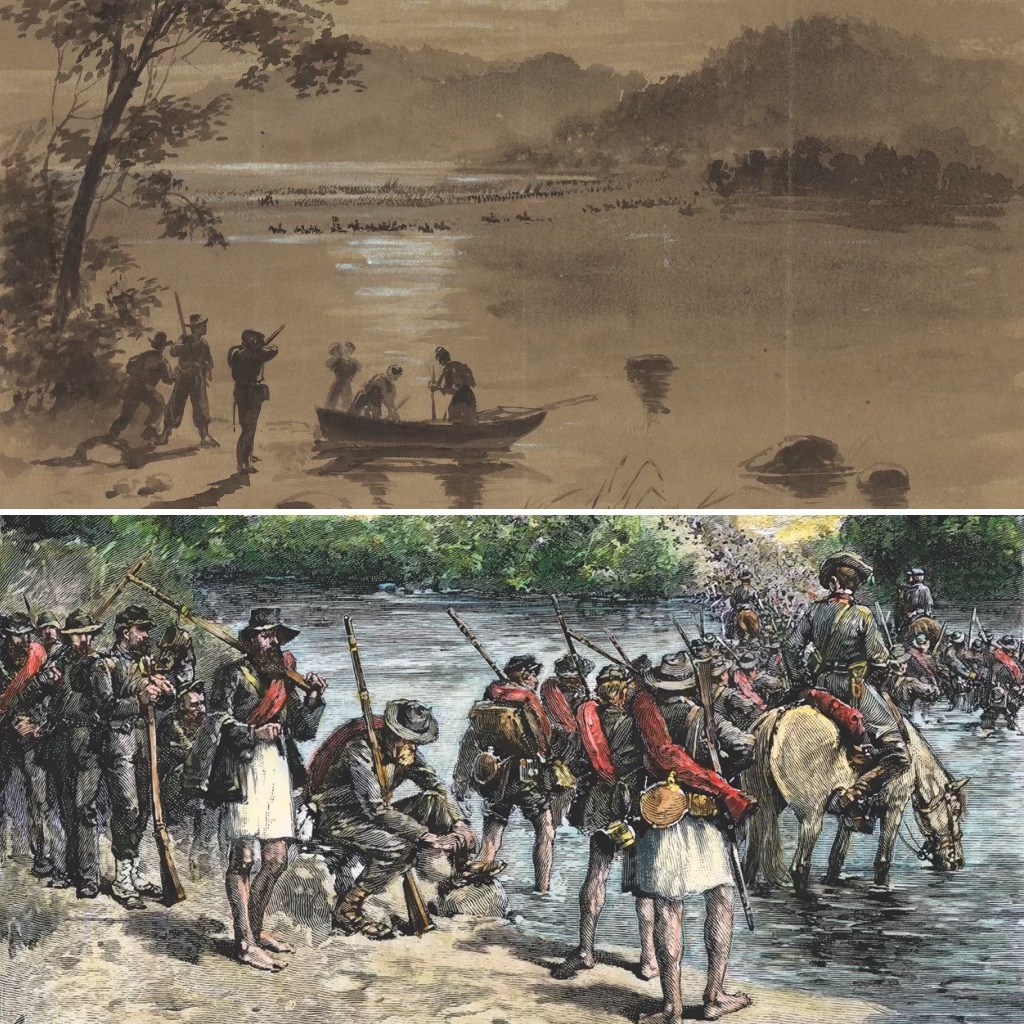

We were on the road in the morning, with our faces turned towards the Potomac – still no rations had been delivered to us – not once had we received our food, since the battle of Manassas, and our breakfast consisted of roasting ears, and apples, which we cooked in any imaginable way, to make them as palatable as possible. About the middle of the day we arrived at the river. And as its blue waters first gladdened our sight – a simultaneous cheer burst from our lips, and we had arrived at the Rubicon at last. Preparations were made for crossing at once – the river was about a hundred yards wide and owing to the fine weather of the last few days not very deep, but the current was very swift, as many of us found to our cost.

We were not long in getting ready. Every soldier consulted his own individual conscience. Some crossed as nature made them – with their bundle stuck on their bayonets, others took off their pants & shoes, and many plunged in just so – and it proved the wisest plan – it was a joyous and ludicrous sight, the river was spotted with the forms of the soldiers crossing, laughing and shouting like truant schoolboys, greeting each mishap of their comrades with roars of Merriment.

The bottom of the river was composed of rocks, rendered smooth as glass by the constant action of the tide, here you would see some tall fellow with his whole bundle elevated in the air on his top of his bayonet, picking his way carefully, when suddenly he would slip and disappear, coming up again with the water pouring out of his gun barrel, and his bundle of all his earthly possessions, gliding quietly down the river on a voyage of discovery – with the water in his eyes, and ears, he would gaze dimly at the retreating wardrobe, and a short Mental Conflict would ensue, as to which he had better give up. He couldn’t get his bundle if he kept his musket, and in the meantime what would he do for clothes. This last thought decided him – down to the bottom would his rifle go, where it is lying there now I suppose, and with a bold sprint he struck out, and would reach the opposite shore a mile or two down, minus his shoes, hats, & gun. Here a short stumpy fellow could be seen wading along with difficulty, the water up to his neck, his eyes looking volumes once on the other side – an inventory was made of the things that were lost.

Confound it – I heard one fellow say, “I don’t mind losing my gun, and shoes much, but I hates to lose my haversack – chock full of good bread and meat that I begged this morning.” And now brisk musket fire – sounding like a miniature battle took place – every soldier fearing that the cartridge inside of his gun had become wet, had to fire it off – and they amused themselves with seeing how far their rifles would throw, and watching the balls skip along the placid waters.

During our onward march we passed through Frederick City, and we [were] very much disappointed at the way we were received. Our boys indulged in glowing anticipations, of how we were to be treated in Maryland, and we led away many a weary hour of marching, in dilating how the ladies would lionize them, how they would feed them, for a soldiers’ first principle of happiness is having a full stomach, without that all other pleasures are vain. And many a wearied footsore reb stumbled, and limped along solacing himself with the thought of how he would charge through the streets of Baltimore, shooting Yankees, and n——s ad lib. And now in their disappointment they seemed to forget that they were not in real Maryland, but in the panhandle, and there was just as much difference between Frederick City and Baltimore as there is between Richmond and Martinsburg.

Most of the windows were closed, and nothing could be seen but the eyes of some scornful female which cast the most defiant glances at them, our Devil may care fellows always met such looks with a merry jest, and joke, that soon caused them to beat a hasty retreat, when at intervals they would pass by some lady whose heightened color, and triumphant excited manner showed plainly enough without noticing the white hand that waved the hankerchief that she wished our cause success with the grace and politeness that spoke well for them. They would revertly bow, and still showed that as dirty and dusty as they are – that gray jacket, so tattered and torn, enclosed the form of many a Chevalier Bayard sans peur et reprache….

Confederate notes were now at premium, orders having been issued by our Generals that the store Keepers in town, should keep open their shops, and sell for our currency, or gets for nothing. And in an hour or two a store would be completely cleaned out, not anything left, the soldiers buying everything they could carry away – leaving the proprietor – his empty shelves, with a bushel or two of Confederate shucks, which were as about as much use to him, as the paper which covered his walls. Many put them carefully away thinking well, they may worth something after all.

The next day we passed through, and camped on the outskirts of Hagerstown. I spent two nights there, and the memory of the devoted kindness to a sick and friendless soldier will always remain green in my memory. And for the sake of such women, it was worthwhile to land any amount of hardships, and shed your blood like water, it was with bitter regrets that I left Dr. McG[’s] hospitable roof, and took my place again in the ambulance, for I had been sick with the camp fever, ever since I had been in Maryland, and after all my trouble in getting here, I determined to see the thing through if there was breath left in my body.

Back we retraced our steps and arrived at Boonsboro on the evening of the fourteenth of September, about four o’clock the regiment took position in a cornfield and fought until night, sustaining little damage, losing only one officer, and he only wounded. Lieutenant A.C. Kell of Co. H. a ball had passed through the upper part of his skull, and instead of numbing him with the shock, only served to madden him and forgetting his rank he seized a musket and fought like a tiger. Lieut. Kell was one of our bravest, and most gallant Officers – and the regiment could ill afford to lose him, even temporarily.

That night I gave my place in the ambulance up to a wounded soldier and tried to march along with the troops but I soon broke down, and coming to an old saw mill on the side of the road I sat down and went to sleep, and was awakened by some one calling my name, opening my eyes I found to my great joy the regiment passing by, they were the rear guard. I thought they were miles in advance. I in company with a comrade took a short cut to Sharpsburg, not before I furnished both Col. C. [Corse] &H. [Lt. Col. Arthur Herbert] with their breakfast of bread and apple butter, which they seemed to enjoy very much, as it was the first meal they had eaten since the day before.

Reprinted with permission of the Virginia Historical Society [“Four Years in the Ranks” VHS Manuscript Call No. Mss5:1 H9162:1]. Robert Lee Hodge writes from Nashville, Tenn. [e-mail: robertleehodge@yahoo.com].