The orders that clattered from the teletype at California’s McClellan Field on March 24, 1942, set off no alarm bells. The message simply announced that a flight of North American B-25 medium bombers would be arriving under the command of a lieutenant colonel named James Doolittle, and that his requests for service and supplies should be accorded the highest priority. Such orders seemed fairly routine at McClellan, formerly known as the Sacramento Air Depot. Situated seven miles northeast of Sacramento, it was the major air depot on the West Coast for arming and preparing bombers and fighter planes for shipment overseas. McClellan’s maintenance crews worked every day on hundreds of airplanes destined for bases throughout the western United States and the Pacific.

But as they would learn during the next five tension-filled days, these big planes, their crews, and their irascible commander were embarking on a mission that was anything but routine. It was, in fact, top secret. For McClellan was to be the final phase in an extraordinary undertaking to prepare men and bombers to launch from an aircraft carrier and strike at the heart of Japan, the mission that would be immortalized for millions of Americans in the book and film Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.

For Jimmy Doolittle, the countdown began two months earlier, on January 17, 1942. That’s when the chief of the Army Air Forces, Lieutenant General Henry “Hap” Arnold called Doolittle in and asked him to take over preparations for this special mission. The mission originated with the heartfelt desire President Roosevelt had expressed to his top commanders two weeks after Pearl Harbor: retaliate by bombing Japan “as soon as humanly possible to bolster morale of America and her Allies.”

The daring scheme to utilize carrier-based bombers evolved because American bombers lacked the range to reach the Japanese mainland. The plan was developed by navy planners and Hap Arnold’s staff, becoming the war’s first major joint Navy-Army Air Forces project. It envisioned the newly commissioned carrier Hornet carrying 16 B-25s to within 400 miles of the Japanese mainland. The aircraft would then take off from the deck, bomb several cities, and fly on to land in China.

Hap Arnold selected Doolittle to head up the project because of his unusual combination of abilities. A flight instructor during World War I, he had raced planes to world records and earned a doctorate in aeronautical engineering from MIT. As a test pilot he helped develop flying by instrument. This accomplishment in “flying blind” won him the sobriquet “master of the calculated risk.” Now at age 45, short, stocky, and intense, he had the skills and experience the job required. “While he was a very good man and kind, he could be a very tough man when the need required,” his navigator, Lieutenant Henry Potter, would later observe of Doolittle. “He knew that you had to try and be precise and do things the right way the first time. If you did, you would get along with him, but he was unwilling to take stupidities from people.”

The timetable was almost impossibly tight for the mission dubbed “Special Aviation Project #1.” It called for the bombers to be aboard the carrier Hornet by April 1, ready for departure from San Francisco Bay. During the next 10 weeks, crews would have to be selected and trained, and bombers would have to be extensively modified and refitted at three different locations—all without alerting anyone to the true nature of the project. Even Roosevelt would not know the details until after the attack.

One of the prerequisites to the mission was to demonstrate that fully loaded B-25s could actually take off safely from the deck of the Hornet. First, a pair of pilots practiced lifting off in B-25s from a special short airfield near Norfolk, Virginia. Then, on February 2, their bombers—loaded lightly with fuel—were hoisted aboard the Hornet and the carrier steamed out of sight of land. With only about 450 feet of useable deck space, each pilot succeeded in taking off. One commented that he rose so rapidly that he nearly struck the structure above the flight deck where the ship commander stood to observe deck operations. None of these participants, including the Hornet’s skipper, knew the purpose of this exercise.

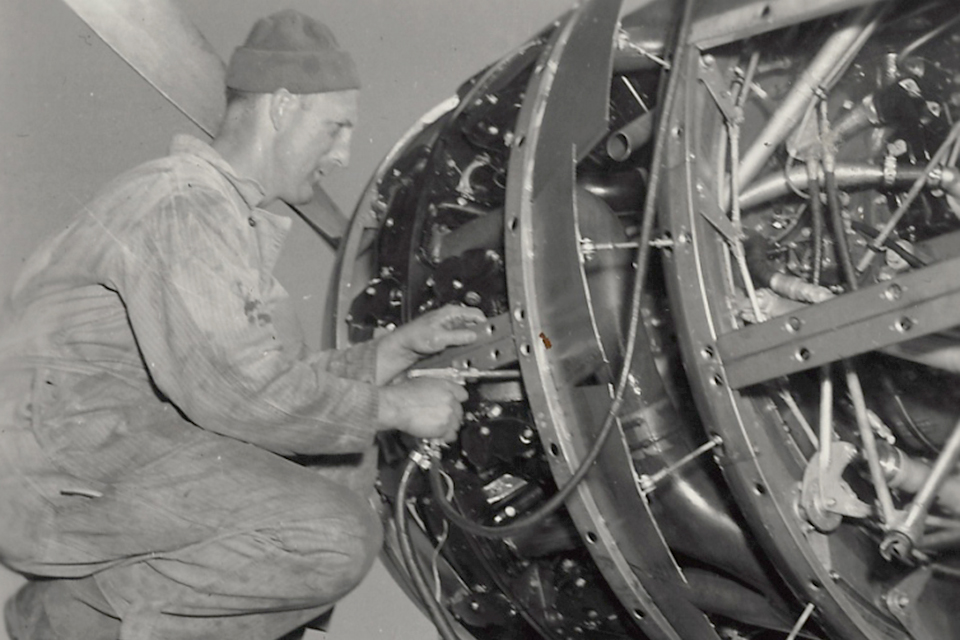

Doolittle, meanwhile, made repeated trips to the research center at Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio. He had the engineers there render drawings for modifying the B-25, including tanks for additional gas. Then he sent the first of 24 bombers to Mid-Continent Airlines in Minneapolis for extensive refitting. Mid-Continent jettisoned enough expendable metal to lighten the craft and make room for the installation of three more gas tanks. These modifications would eventually nearly double the fuel capacity, from 646 to 1,141 gallons—enough to get a plane to Japan, drop 2,000 pounds of bombs, and then hightail it to a landing field in China. To meet his timetable, Doolittle had to repeatedly invoke his top priority authorization from Hap Arnold. “I was extremely unpopular everywhere I went,” he said, “but with that top priority straight from the top, I got what I needed and I got it quickly.”

For the vital human element—the five-man bomber crews—Doolittle turned to the 17th Bombardment Group stationed at Pendleton, Oregon. This was the outfit with the most experience flying the new B-25 Mitchell Bomber, named for Billy Mitchell, the controversial early advocate of air power. On February 3, four squadrons were ordered to Columbia, South Carolina, where each man stepped forward to volunteer for a mission he knew nothing about. At Doolittle’s request, squadron commanders selected 140 men—enough to make up 24 five-man crews. Only 16 planes were needed to attack Japan, and the eight extra crews and their planes provided “a 50 percent buffer” against losses, as Doolittle put it.

Everyone was assembled at Eglin Field in Florida by March 3 when Doolittle arrived. This base was near the sea so that the navigators could practice over-water navigation. It had an auxiliary field for training in short-field takeoffs and was relatively secluded, free from curious eyes. Doolittle introduced himself in typically blunt fashion—“My name’s Doolittle”—and told the men the project “will be the most dangerous thing any of you have ever done. Any man can drop out and nothing will ever be said about it. This entire mission must be kept top secret.”

He did not spell out what the mission was, but during the next couple of days he did divulge some details to the top eight officers he had appointed as his staff. Lieutenant Henry (Hank) Miller, a navy flying instructor, was assigned to teach the B-25 pilots how to make short-field takeoffs to simulate the carrier experience. “I figured something big was happening,” he later said, but like the pilots he was teaching, he was kept in the dark. Miller, it turned out, had never even seen a B-25, let alone flown one. That was quickly remedied, and he and Doolittle hit it off. “We were both old sourdoughs from Alaska—he from Fairbanks and I from Nome,” Doolittle recalled. “I found that we had both been boxers. So we had a great deal in common.”

To learn how to take off with a 31,000-pound fully loaded bomber from a runway less than 500 feet long, Miller’s students had to unlearn old habits. They were accustomed to taking off from runways up to a mile long and achieving plenty of airspeed before liftoff. Miller had to teach them to take off at a speed so slow the engines almost stalled as the plane lifted off in the short space of a carrier deck.

This harrowing experience, Doolittle noted, “took some courage and was very much against their natural instincts.” It required repeated drilling because pilots tended to revert to conventional takeoff technique. In fact, two pilots stalled and crashed their planes on takeoff. No one was hurt, but the number of planes and crews was now reduced to 22.

There were simulated dogfights as well, so that pilots could practice evasive actions. “We also did a quite a bit of low-level, minimum-altitude flying, which gave us considerable amount of pleasure, particularly on the beaches of Florida,” recalled Henry Potter, the lead navigator for the project. “At that time there were no minimum restrictions so we were able to go up and down the beaches, watching people scramble from the airplanes as they flew over.”

Although Doolittle was not slated to fly in the raid himself, he took Miller’s short-takeoff training course between frequent trips back and forth to Washington and Wright Field to iron out myriad details. Then, when one of the pilots became ill, he took over his plane and crew. Doolittle fully intended to command the actual raid in person—and on one of his flights to Washington he talked a reluctant Hap Arnold into letting him do it.

To deal with gun and bomb problems, Doolittle turned to his inventive 27-year-old armaments officer, Captain Charles (Ross) Greening. At Eglin, Greening tackled issues with the B-25’s guns. The twin 50-caliber machine guns mounted in the lower turret proved to be practically useless. The mechanism that rotated the turret failed repeatedly. And the guns were so complicated, “I thought a man could learn to play the violin well enough for Carnegie Hall before he could learn to fire that thing,” commented Doolittle. Greening suggested the lower turret be removed, and Doolittle agreed. In its place they would install a 60-gallon gas tank that could be gradually refilled by a crewman from ten five-gallon cans stored in the rear compartment.

The B-25 lacked any rear guns, a problem Greening solved with an imaginative stroke of deception. Two long broomsticks painted black were bolted through holes bored in the tail. At a distance they gave the appearance of being guns and might deter Japanese fighters from rear attacks.

Another issue for Greening was the Norden bombsight, the secret mechanism designed for high-altitude precision bombing. The projected attack on Japan would occur at low altitudes, where the Norden would be far less effective. Moreover, no one wanted to risk the possibility that a crash would allow this top-secret weapon to fall into the hands of the Japanese. Doolittle decided to remove the Norden and substitute what Raider bombardiers referred to as “the 20-cent bombsight,” because Greening had crafted it in the shops at Eglin from a sighting bar and piece of aluminum that together cost only 20 cents. It worked essentially like a gun sight, and during tests at Eglin proved to be more accurate at 1,500 feet than the $10,000 Norden.

Doolittle handled another armaments problem by contacting the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. He needed incendiaries to supplement the demolition bombs in the plane’s 2,000-pound bomb load. The arsenal put together 500-pound clusters of incendiary bomblets that would scatter when dropped at low altitudes. These became the basis for incendiary bombs used by the United States throughout the war.

While Doolittle’s crews were struggling to log sufficient flying time between modifications on their planes, their transport and launching platform—the carrier Hornet—was wending its way through the Panama Canal. It was bound for San Francisco. Soon Doolittle and his men would also be headed west. Less than three weeks after the project’s arrival at Eglin, Hap Arnold relayed to Doolittle the navy’s seven-word coded message: “Tell Jimmy to get on his horse.” This was the signal for the final stage of the frantic countdown before the Doolittle Raid—and none too soon. The war situation in the Pacific was growing increasingly dire. The Dutch East Indies and Burma had fallen to the Japanese, and the Philippines were on the brink.

Doolittle and his own B-25 arrived at McClellan Field on March 25. He immediately met with the field’s engineering officer and two of his lieutenants to brief them on the work that needed to be done. “This project is a highly confidential one,” he told them. “As a matter of fact I am having to notify General Arnold in code that I arrived.”

Even after the refitting carried out in Minneapolis and at Eglin Field, plenty of work remained to be done. Doolittle’s to-do list consisted of two dozen items, ranging from a complete inspection of all 22 planes to switching the bombsights, and the installation of new propellers on the twin engines of each plane. The list also made clear: “Under no circumstances is any equipment to be removed or tampered with on these airplanes except by order of Col. Doolittle” or three other designated officers.

Some jobs went smoothly. Each plane’s 210-pound liaison radio was removed to save weight and to ensure that radio silence was maintained during the raid. A 60-gallon fuel tank was installed where the lower gun turret had been removed. But almost from the beginning, problems plagued the work at McClellan. The time schedule allotted was extremely short. By the time the entire flight of bombers had landed on March 26, McClellan’s maintenance crews had less than five days to work their magic. Doolittle complicated the work by insisting that no work begin on a particular modification unless the new component was in hand. To everyone’s consternation, many parts that had been ordered by Doolittle and others were stalled somewhere in the supply pipeline.

While mechanics worked with what they had, urgent requests flooded the teletype lines. McClellan staffers scoured the country for hydraulic check valves to fix a problem with the top gun turret and for plate glass to replace the Plexiglass that distorted the navigator’s three windows. They also had to track down four 500-pound practice bombs to test the bomb release mechanism after the fuel tanks were installed. After much confusion a pair of drill bombs used in ground loading practice were located in San Francisco and sent down by truck.

Among the missing parts were six still cameras and 16 movie cameras to be installed on the planes to record the attacks. “I have done everything but sleep on the floors of airline terminals waiting for priorities, phone calls, and staying up half the night trying to iron out some of the wrinkles that seem to be turning up,” said Henry Rognati, a photographic specialist flown in from Wright Field in Ohio.

The secrecy enveloping the project only added to the frustration. McClellan’s electronics specialist, Leslie Smith, recalled that the lack of information about its importance and urgency led him and his mates to believe they were handling just another job. “We were working three shifts,” he said. “The atmosphere was much like a war plant; there were almost 15,000 employees at the depot and they were working on hundreds of airplanes.” As for Jimmy Doolittle, Smith noted, he was only a light colonel at a field loaded with brass. “To many of us, Doolittle was just another GI.”

Nonetheless, some of the field’s more than 125 civilian technical specialists assigned to the project noticed signs that it might be something special. For one thing, there were all those strange modifications—the cheap bombsight, for example, and those painted broomsticks jutting out the rear. For another, noted Robert Heiss, an electrician, the usual procedure was for planes to be flown into the field by ferry pilots who immediately left. But the entire Doolittle squadron flew in, with full crews, and stuck around.

In fact, Paul Hammitt, a sheet metal specialist, remembered the ever-present crewmen as “overanxious,” hovering over the mechanics and grilling them as they worked. McClellan mechanics were reminded of automobile customers hanging around while their car was being fixed, continuously making annoying and technically untenable suggestions. Indeed, Doolittle, while telling his crews that the depot had “good mechanics” who will “take care of anything that’s wrong with your ships,” warned them to keep a close eye on the work.

All the pilots winced at the way some of the mechanics revved their engines. In his classic account Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, Captain Ted Lawson described one mechanic who sped up his engines so fast that the new propeller blades picked up dirt that pockmarked their tips. “I caught another one trying to sandpaper the imperfections away and yelled at him until he got out some oil and rubbed it on the places which he had sandpapered. I knew that salt air would make those prop tips pulpy where they had been scraped.”

“We couldn’t tell them why we wanted them to be so careful,” Lawson wrote. “I guess we must have acted like the biggest bunch of soreheads those mechanics ever saw, but we kept beefing until Doolittle got on the long-distance phone, called Washington, and had the work done the way we wanted it done.”

Doolittle did call Hap Arnold—more than once. “Things are going too slowly out here,” he complained. “They’re treating this job as ‘routine.’” He asked Arnold to “personally build a fire under these people.” Doolittle prowled the field incessantly looking for problems and demanded that the mechanics do things “his way,” electrician Robert Heiss recalled, even when official technical orders dictated otherwise. Senior mechanic Eugene Thomsen remembered that there was a shortage of men qualified to start engines. As a result, a qualified mechanic would start the plane’s two engines and then go on to another nearby plane, leaving a junior man in the pilot’s compartment to monitor instruments. On one such occasion, Doolittle peered up through the hatch at the bottom of the plane and asked the junior what he was doing. When the hapless man replied “I don’t know,” Doolittle blew up.

Later, in his memoir I Could Never Be So Lucky Again, Doolittle griped that “the civilian maintenance crew went about their assignment at a leisurely pace.” But perhaps that was just the view of an impatient project leader: electrician Robert Heiss denied there was any slacking off, explaining that the mechanics were operating at the fastest possible speed consistent with the nature of the technical work. Besides, they also had commitments to deliver airplanes to other military commanders.

When time allowed and their planes were available, the pilots continued to practice short-field takeoffs with their navy flying instructor, Hank Miller, at Glenn County Airport in the town of Willows. It was fairly remote, 85 miles north of Sacramento, and offered a semblance of secrecy. Besides, Doolittle’s old friend Floyd Nolta had established a flying business there, offering crop dusting and other services. Runway 13-31 was marked off to replicate the flight deck of the carrier Hornet. Afterward, some crews adjourned to The Blue Gum, a popular tavern in town.

During the final day or so before his planes departed McClellan, Doolittle grew increasingly impatient. His anger over incidents with the mechanics still rankled, and a number of crucial parts he had requested had not yet arrived. Among the parts still missing were hydraulic check valves, the 270-pound fuel tanks to replace the smaller tanks in the bomb bay, and the glass windows for the navigator’s compartments. Without those components, work could not be completed by the deadline. Though regulations ordinarily forbade releasing planes until work had been finished, Doolittle’s orders from Washington released his planes for takeoff on March 31 for the short hop to Alameda Naval Air Station, where the Hornet waited at dock to hoist them aboard. (The windows, along with some spare parts, would show up three days later, in time to be lowered from a navy blimp onto the Hornet’s deck as the carrier steamed out of San Francisco Bay.)

Still, Doolittle would have the last word. On April 1, just before leaving McClellan to join his crews, Doolittle was handed a standard form asking him to evaluate the quality of McClellan’s service. He scrawled diagonally across the form in large print a single five-letter word: “LOUSY.”

The following day, while the Hornet prepared to depart San Francisco Bay, its deck laden with 16 B-25s, the commander of McClellan Field attempted to defend the installation against Doolittle’s criticism. In a report teletyped to his superior at Wright Field, Colonel John Clark noted Doolittle’s “considerable annoyance and dissatisfaction at the last minute before departure.” He mentioned the field’s shortage of trained personnel and asserted that, in any case, “the work was well organized and executed in a manner which should bring credit rather than discredit upon those who were actually in charge.”

But the sting of Doolittle’s rebukes was considerably softened a few weeks later when McClellan’s much-maligned mechanics learned why that light colonel named Doolittle and his crews had been so demanding. President Roosevelt’s announcement of the successful aerial attack on Tokyo and other Japanese cities on April 18 said the bombers had taken off from “Shangri-la,” a mythical Tibetan sanctuary. But the men at McClellan knew better. The critical mission, with its profound impact on American morale and Japanese military strategy, would never have succeeded without their help. Years later, they still felt pride in their role in the frenzied countdown to a historic mission. They only regretted that 15 of the bombers and seven lives were lost after the unexpected appearance of a Japanese ship forced Doolittle to launch 250 miles earlier than planned.

Still, the general feeling at McClellan, electrician Robert Heiss later recalled, was “we got them there.”

Ronald H. Bailey is the author of four books on World War II. He once devoted more than two months to reporting on the U.S. Navy for the old weekly Life magazine, spending time on carriers in both the Mediterranean and the Pacific. His wildest ride was transferring between a carrier and a destroyer in a bosun’s chair slung over the water. Nearly 50 years later, a photograph of this adventure still hangs in his office in upstate New York. Susan Zimmerman, a freelance writer who lives in St. Louis, contributed reporting to the article.