Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on Dec. 11, 1889, Coulson Norman Mitchell graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1912 with a degree in engineering before embarking on a bicycle tour of England and Scotland with his father. On his return to Canada the young man accepted a position as a construction engineer and in 1913 helped right a railside grain elevator on the east side of Winnipeg when subsidence threatened to topple it. The skills he learned on the job would prove invaluable in the forthcoming war.

Mitchell enlisted as a sapper in the Canadian Engineers on Nov. 10, 1914. Brothers Stanley and Gladstone also enlisted—the former dying of appendicitis before leaving Canada, the latter being invalided home with a gunshot wound in late 1917. In June 1915 Coulson (“Mike” to family and friends) arrived in England with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), and two months later he sailed for France.

He was soon sent to Alveringem, Belgium, with the Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps, attached to the Belgian army as a tunneler involved in mining and countermining operations. On his return to England that fall Mitchell was promoted to sergeant, and by the spring of 1916 he’d risen to lieutenant. He returned to France that summer and in December was awarded the Military Cross for conspicuous gallantry amid countermining operations.

In the spring of 1918 Mitchell was promoted to captain and soon assigned to the 4th Canadian Engineers Battalion, supporting the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. That August 8 the final Allied offensive (the “Hundred Days”) opened with the Battle of Amiens. As the static Western Front was suddenly set in motion, mining proved impractical. Given their expertise with explosives, tunnelers like Mitchell were repurposed, sent forward to decommission German demolition charges ahead of the CEF advance.

In early October, having broken the German line at the Canal du Nord, the CEF pressed north of Cambrai as a British pincer movement to the south sought to encircle the city to avoid a bitter street fight. On the night of October 8–9 Mitchell was ordered to take a patrol and reconnoiter, demine where necessary and secure crossings of the Canal de l’Escaut into Escaudoeuvres. The main force would follow at dawn.

The withdrawing Germans had already destroyed the first bridge over the canal. Mitchell’s team managed to cut wires to explosives beneath the second span. While the main bridge into town also remained standing, enemy engineers had mined it for demolition. Approaching the span with three men, Mitchell posted a sentry at either end and clambered beneath the roadway with a sergeant. The fleeing Germans had left ladders and scaffolding in place, enabling the pair to quickly sever electrical leads to the mines. When counterattacking Germans threatened the east end of the bridge, Mitchell joined the sole sentry to fight off the assault. He then returned beneath the span to disarm the remaining charges.

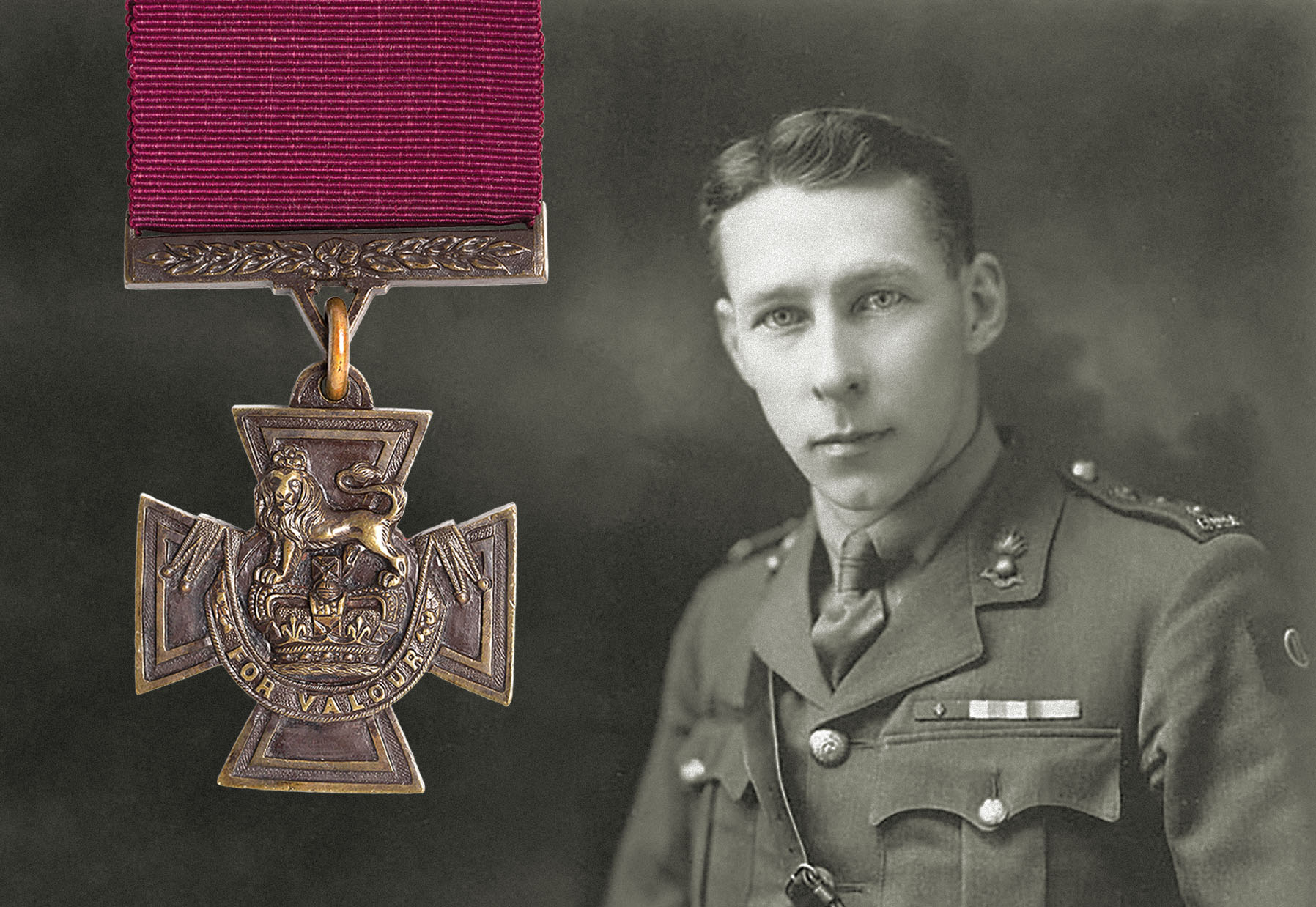

The sergeant and sentry received Distinguished Conduct Medals, while Mitchell was given the Victoria Cross. “It was entirely due to his valor and decisive action,” read the citation, “that this important bridge across the canal was saved from destruction.”

Mitchell survived the war without a scratch. Following demobilization in Ottawa on May 2, 1919, he resumed work in Winnipeg and in 1922 married Gertrude Hazel Bishop. Four years later the couple moved to Montreal. During World War II Mitchell served as a Royal Canadian Engineers trainer both at home and overseas. Retiring from the service as a lieutenant colonel, Mitchell returned to Montreal, where he died at age 78 on Nov. 17, 1978. MH

This article appeared in the May 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: